- Dune (film)

-

This article is about the 1984 film. For other related films, see Dune (franchise)#Film and television adaptations.

Dune

Promotional film poster for DuneDirected by David Lynch Produced by Raffaella De Laurentiis Screenplay by David Lynch Based on Dune by

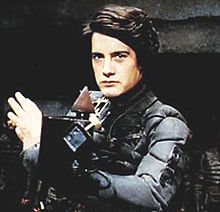

Frank HerbertStarring Kyle MacLachlan

Francesca Annis

Everett McGill

Sting

Max von Sydow

Jose Ferrer

Siân Phillips

Virginia Madsen

Alicia Witt

Sean YoungMusic by Toto

Brian Eno (Prophecy Theme)

Marty Paich (additional music)Cinematography Freddie Francis Editing by Antony Gibbs Distributed by Universal Pictures Release date(s) December 14, 1984 Running time 137 minutes Country United States Language English Budget $40 million Box office $29,781,000 Dune is a 1984 science fiction film written and directed by David Lynch, based on the 1965 Frank Herbert novel of the same name. The film stars Kyle MacLachlan as Paul Atreides, and includes an ensemble of well-known American and European actors in supporting roles. It was filmed at the Churubusco Studios in Mexico City and included a soundtrack by the band Toto. The plot concerns a young man foretold as the "Kwisatz Haderach" who will lead the native Fremen of the titular desert planet to victory over the malevolent House Harkonnen.

After the success of the novel, attempts to adapt Dune for a film began as early as 1971. A lengthy process of development hell followed throughout the 1970s, during which time both Arthur P. Jacobs and Alejandro Jodorowsky tried to bring their visions to the screen. In 1981, Lynch was hired as director by executive producer Dino De Laurentiis.

The film was not well-received by critics and performed poorly at the American box office. Dune has been called "obscenely homophobic", while its depiction of the Baron Harkonnen, head of House Harkonnen and antagonist of Paul Atreides, as suffering from suppurating sores has been seen as an example of how references to AIDS penetrated popular culture in the 1980s. Upon its release, Lynch distanced himself from the project, stating that pressure from both producers and financiers restrained his artistic control and denied him final cut. At least three different versions of Dune have been released worldwide. In some cuts Lynch's name is replaced in the credits with the name Alan Smithee, a pseudonym formerly used by directors who wished not to be associated with a film for which they would normally be credited.

Contents

Plot

In the far future, the known universe is ruled by Padishah Emperor Shaddam Corrino IV; the most precious substance in his sprawling feudal galactic empire is the spice melange, which extends life, expands consciousness, and is vital to space travel. The Spacing Guild and its prescient Navigators use the spice to "fold space" and safely guide interstellar ships to any part of the universe instantaneously.

Sensing a potential threat to spice production, the Guild sends an emissary to demand an explanation from the Emperor, who confidentially shares his plans to destroy House Atreides. The popularity of Duke Leto Atreides has grown, and he is suspected to be amassing a secret army using sonic weapons called Weirding Modules, making him a threat to the Emperor. Shaddam's plan is to give the Atreides control of the planet Arrakis, the only source of spice, and to have them ambushed there by their longtime enemies, the Harkonnens. The Navigator commands the Emperor to kill the Duke's son, Paul Atreides, a young man who dreams prophetic visions of his purpose. The order draws the attention of the Bene Gesserit sisterhood, as Paul is tied to their centuries-long breeding program which seeks to produce the superhuman Kwisatz Haderach. Paul is tested by the Bene Gesserit Reverend Mother Gaius Helen Mohiam. With a deadly gom jabbar at his throat, Paul is forced to place his hand in a box which subjects him to excruciating pain. He passes to Mohiam's satisfaction.

Meanwhile, on the industrial world of Giedi Prime, the sadistic Baron Vladimir Harkonnen tells his nephews Glossu Rabban and Feyd-Rautha about his plan to eliminate the Atreides by manipulating someone into betraying the Duke. The Atreides leave Caladan for Arrakis, a barren desert planet plagued by gigantic sandworms and populated by the Fremen, mysterious people who have long held a prophecy that a messiah would come to lead them to freedom. Upon arrival on Arrakis, Leto is informed by one of his right-hand men, Duncan Idaho, that the Fremen have been underestimated, as they exist in vast numbers and could prove to be powerful allies. Leto gains the trust of Fremen, but before the Duke can establish an alliance with them, the Harkonnens launch their attack.

While the Atreides had anticipated a trap, they are unable to withstand the attack, supported by the Emperor's elite troops, the Sardaukar, and aided by a traitor within House Atreides itself, Dr. Wellington Yueh. Captured, Leto dies in a failed attempt to assassinate the Baron Harkonnen using a poison gas capsule planted in his tooth by Dr. Yueh. Leto's concubine Jessica and his son Paul escape into the deep desert, where they manage to join a band of Fremen. Paul emerges as Muad'Dib, the leader the Fremen have been waiting for. Paul teaches the Fremen to use the Weirding Modules and begins targeting mining production of spice. Within two years, spice production is effectively halted. The Emperor is warned by the Spacing Guild of the situation on Arrakis. The Guild fears that Paul will consume the Water of Life. These fears are revealed to Paul in a prophetic dream; he drinks the Water of Life and enters a coma. Awaking, he is transformed and gains control of the sandworms of Arrakis. He has discovered that water kept in huge caches by the Fremen can be used to destroy the spice. Paul has also seen into space and the future; the Emperor is amassing a huge invasion fleet above Arrakis to regain control of the planet and the spice.

Upon the Emperor's arrival at Arrakis, he executes Rabban for failing to remedy the spice situation. Paul launches a final attack against the Harkonnens and the Emperor at the capital city of Arrakeen. His Fremen warriors defeat the Emperor's legions of Sardaukar, while Paul's sister Alia kills Baron Harkonnen. Paul faces the defeated Emperor and relieves him of power, then engages Feyd-Rautha in a duel to the death. After Paul defeats Feyd, rain falls on Arrakis. Alia declares, "And how can this be? For he is the Kwisatz Haderach!"

Cast

In credited order:

- Francesca Annis as Lady Jessica

- Leonardo Cimino as The Baron's Doctor

- Brad Dourif as Piter De Vries

- José Ferrer as Padishah Emperor Shaddam IV

- Linda Hunt as the Shadout Mapes

- Freddie Jones as Thufir Hawat

- Richard Jordan as Duncan Idaho

- Kyle MacLachlan as Paul Atreides

- Virginia Madsen as Princess Irulan

- Silvana Mangano as Reverend Mother Ramallo

- Everett McGill as Stilgar

- Kenneth McMillan as Baron Vladimir Harkonnen

- Jack Nance as Captain Iakin Nefud

- Siân Phillips as Reverend Mother Gaius Helen Mohiam

- Jürgen Prochnow as Duke Leto Atreides

- Paul L. Smith as The Beast Rabban (credited as Paul Smith)

- Patrick Stewart as Gurney Halleck

- Sting as Feyd-Rautha

- Dean Stockwell as Dr. Wellington Yueh

- Max von Sydow as Dr. Kynes

- Alicia Witt as Alia (credited as Alicia Roanne Witt)

- Sean Young as Chani

- Honorato Magaloni as Otheym (credited as Honorato Magalone)

- Judd Omen as Jamis

- Molly Wryn as Harah, Jamis' wife

Production

The film is an adaptation of the first of a series of novels (see Dune, by Frank Herbert) and incorporating some elements from the later novels. The pre-production process was slow and problematic, and the project was handed from director to director.[1]

Early stalled attempts

In 1971, the production company Apjac International (APJ) (headed by Arthur P. Jacobs) optioned the rights to film Dune. As Jacobs was busy with other projects, such as the sequel to Planet of the Apes, Dune was delayed for another year. Jacobs' first choice for director was David Lean, but he turned down the offer. Charles Jarrott was also considered to direct. Work was also under way on a script while the hunt for a director continued. Initially, the first treatment had been handled by Robert Greenhut, the producer who had lobbied Jacob to make the movie in the first place, but subsequently Rospo Pallenberg was approached to write the script, with shooting scheduled to begin in 1974. However, Jacobs died in 1973.

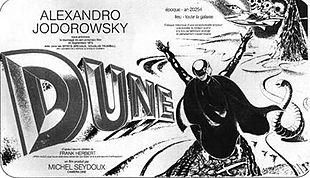

In December 1974, a French consortium led by Jean-Paul Gibon purchased the film rights from APJ. Alejandro Jodorowsky was set to direct. In 1975, Jodorowsky planned to film the story as a ten-hour feature, in collaboration with Salvador Dalí, Orson Welles, Gloria Swanson, David Carradine, Geraldine Chaplin, Alain Delon, Hervé Villechaize and Mick Jagger. It was at first proposed to score the film with original music by Karlheinz Stockhausen, Henry Cow and Magma; later on, the soundtrack was to be provided by Pink Floyd.[2] Jodorowsky set up a pre-production unit in Paris consisting of Chris Foss, a British artist who designed covers for science fiction periodicals, Jean Giraud (Moebius), a French illustrator who created and also wrote and drew for Metal Hurlant magazine, and H. R. Giger. Moebius began designing creatures and characters for the film, while Foss was brought in to design the film's space ships and hardware. Giger began designing the Harkonnen Castle based on Moebius' storyboards. Jodorowsky's son Brontis Jodorowsky was to play Paul Atreides. Dan O'Bannon was to head the special effects department.

Salvador Dalí was cast as the Emperor. Dalí later demanded to be paid $100,000 per hour; Jodorowsky agreed, but tailored Dalí's part to be filmed in one hour, drafting plans for other scenes of the emperor to use a mechanical mannequin as substitute for Dalí. (According to Giger, Dalí was "later invited to leave the film because of his pro-Franco statements").[3] Just as the storyboards, designs, and script were finished, the financial backing dried up. Frank Herbert travelled to Europe in 1976 to find that $2 million of the $9.5 million budget had already been spent in pre-production, and that Jodorowsky's script would result in a 14-hour movie ("It was the size of a phonebook", Herbert later recalled). Jodorowsky took creative liberties with the source material, but Herbert said that he and Jodorowsky had an amicable relationship.

De Laurentiis's stalled attempts

The rights for filming were sold once more, this time to Dino de Laurentiis. Although Jodorowsky was embittered by the experience, he stated that the Dune project changed his life. Dan O'Bannon entered a psychiatric hospital after the production failed, and worked on 13 scripts; his 13th became Alien.[4] In 1978, De Laurentiis commissioned Herbert to write a new screenplay, but Herbert's 175-page script was rejected – an average script is 90 to 140 pages long.

De Laurentiis then hired director Ridley Scott in 1979, with Rudolph Wurlitzer writing the screenplay and H.R. Giger retained from the Jodorowsky production. Scott intended to split the book into two movies. He worked on three drafts of the script, using The Battle of Algiers as a point of reference, before moving on to direct another science fiction film, Blade Runner (1982). As he recalls, the pre-production process was slow, and finishing the project would have been even more time-intensive:

But after seven months I dropped out of Dune, by then Rudy Wurlitzer had come up with a first-draft script which I felt was a decent distillation of Frank Herbert's. But I also realised Dune was going to take a lot more work — at least two and a half years' worth. And I didn't have the heart to attack that because my older brother Frank unexpectedly died of cancer while I was prepping the De Laurentiis picture. Frankly, that freaked me out. So I went to Dino and told him the Dune script was his.

—— From Ridley Scott: The Making of his Movies by Paul M. SammonLynch's screenplay and direction

In 1981, the nine-year film rights were set to expire. De Laurentiis re-negotiated the rights from the author, adding to them the rights to the Dune sequels (written and unwritten). After seeing The Elephant Man, Raffaella De Laurentiis decided that David Lynch should direct the movie. Around that time Lynch received several other directing offers, including Return of the Jedi. He agreed to direct Dune and write the screenplay even though he had not read the book, known the story, or even been interested in science fiction.[5] David Lynch worked on the script for six months with Eric Bergen and Christopher De Vore. The team yielded two drafts of the script before it split over creative differences. Lynch would subsequently work on five more drafts.

On March 30, 1983, with the 135-page 6th draft of the script, Dune finally began shooting. It was shot entirely in Mexico. With a budget of over 40 million dollars, Dune required 80 sets built on 16 sound stages and a total crew of 1700. Many of the exterior shots were filmed in the Samalayuca Dunes in Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua.

Editing

Upon completion, the rough cut of Dune without post-production effects ran over four hours long, but Lynch's intended cut of the film (as reflected in the 7th and final draft of the script) was three hours long.

However, Universal Pictures and the film's financiers expected a standard, two-hour cut of the film. To reduce the run time, producers Dino De Laurentiis, Raffaella De Laurentiis, and director David Lynch excised numerous scenes, filmed new scenes that simplified or concentrated plot elements, and added voice-over narrations, plus a new introduction by Virginia Madsen. Contrary to popular rumors, Lynch made no other version of the movie besides the theatrical cut; no three to six hour version ever reached the post-production stage. However, several longer versions have been spliced together.[6] Although Universal has approached Lynch for a possible director's cut of the film, Lynch has declined every offer and prefers not to discuss Dune in interviews.[7]

Release

Dune premiered in Washington, D.C., on December 3, 1984, at The Kennedy Center and was released worldwide on December 14. Pre-release publicity was extensive, not only because it was based on a best-selling novel, but because it was directed by David Lynch, who had success with Eraserhead and The Elephant Man. Several magazines followed the production and published articles praising the film before its release,[8] all part of the advertising and merchandising of Dune, which also included a documentary for television as well as items placed in toy stores.[9]

Reception

The film was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Sound (Bill Varney, Steve Maslow, Kevin O'Connell and Nelson Stoll).[10]

Roger Ebert gave Dune 1 star out of 4 and wrote "This movie is a real mess, an incomprehensible, ugly, unstructured, pointless excursion into the murkier realms of one of the most confusing screenplays of all time."[11] Ebert added: "The movie's plot will no doubt mean more to people who've read Herbert than to those who are walking in cold,"[11] and later named it "the worst movie of the year."[12] On At The Movies with Gene Siskel and Ebert, Siskel began his review by saying "it's physically ugly, it contains at least a dozen gory gross-out scenes, some of its special effects are cheap — surprisingly cheap because this film cost a reported $40-45 million — and its story is confusing beyond belief. In case I haven't made myself clear, I hated watching this film."[13] The film was later listed as the worst film of 1984 in their "Stinkers of 1984" episode.[14] Other negative reviews focused on the same issues as well as on the length of the film.[15]

Janet Maslin of The New York Times also gave Dune a negative review of 1 star out of 5. She said that, "Several of the characters in Dune are psychic, which puts them in the unique position of being able to understand what goes on in the movie" and explained that the plot was "perilously overloaded, as is virtually everything else about it."[16]

Variety gave Dune a less negative review stating "Dune is a huge, hollow, imaginative and cold sci-fi epic. Visually unique and teeming with incident, David Lynch's film holds the interest due to its abundant surface attractions but won't, of its own accord, create the sort of fanaticism which has made Frank Herbert's 1965 novel one of the all-time favorites in its genre." They also commented on how "Lynch's adaptation covers the entire span of the novel, but simply setting up the various worlds, characters, intrigues and forces at work requires more than a half-hour of expository screen time." They did enjoy the cast and said that "Francesca Annis and Jurgen Prochnow make an outstandingly attractive royal couple, Siân Phillips has some mesmerizing moments as a powerful witch, Brad Dourif is effectively loony, and best of all is Kenneth McMillan, whose face is covered with grotesque growths and who floats around like the Blue Meanie come to life."[17]

Richard Corliss, of Time, magazine gave Dune a negative review, stating that "Most sci-fi movies offer escape, a holiday from homework, but Dune is as difficult as a final exam. You have to cram for it." He noted that "MacLachlan, 25, grows impressively in the role; his features, soft and spoiled at the beginning, take on a he-manly glamour once he assumes his mission." He ended by saying "The actors seem hypnotized by the spell Lynch has woven around them — especially the lustrous Francesca Annis, as Paul's mother, who whispers her lines with the urgency of erotic revelation. In those moments when Annis is onscreen, Dune finds the emotional center that has eluded it in its parade of rococo decor and austere special effects. She reminds us of what movies can achieve when they have a heart as well as a mind."[18]

Film scholar Robin Wood called Dune "the most obscenely homophobic film I have ever seen",[19] whereas Dennis Altman suggested that the film showed how "AIDS references began penetrating popular culture" in the 1980s, asking, "Was it just an accident that in the film Dune the homosexual villain had suppurating sores on his face?"[20]

While most critics were negative towards Dune, critic and science fiction writer Harlan Ellison was of a different opinion at the time. In his 1989 book of film criticism, Harlan Ellison's Watching, he says that the $42 million production failed because critics were denied screenings at the last minute after several re-schedules, a decision by Universal that, according to Ellison, made the film community feel nervous and negative towards Dune before its release.[21] Ellison eventually became one of the film's few positive reviewers.

The few more favorable reviews praised Lynch's noir-baroque approach to the film. Others compare it to other Lynch films that are equally hard to access, such as Eraserhead, and assert that in order to watch it, the viewer must first be aware of the Dune universe. In the years since its initial release Dune has gained more positive reviews from on-line critics[22] and viewers.[23]

As a result of its poor commercial and critical reception, all initial plans for Dune sequels were canceled. It was reported that David Lynch was working on the screenplay for Dune Messiah[24] and was hired to direct a second and a third Dune film. In retrospect, Lynch acknowledged he should never have directed Dune:[25]

I started selling out on Dune. Looking back, it's no one's fault but my own. I probably shouldn't have done that picture, but I saw tons and tons of possibilities for things I loved, and this was the structure to do them in. There was so much room to create a world. But I got strong indications from Raffaella and Dino De Laurentiis of what kind of film they expected, and I knew I didn't have final cut.[26]

In the introduction for his 1985 short story collection Eye, Frank Herbert discussed the film's reception and his participation in the production, complimented Lynch, and listed scenes that were shot but left out of the released version. He wrote, "I enjoyed the film even as a cut and I told it as I saw it: What reached the screen is a visual feast that begins as Dune begins and you hear my dialogue all through it." Herbert also commented, "I have my quibbles about the film, of course. Paul was a man playing god, not a god who could make it rain."[27]

See also

- Dune (soundtrack)

- Frank Herbert's Dune, TV miniseries (2000)

- Frank Herbert's Children of Dune, TV miniseries (2003)

- Technology of the Dune universe

References

- ^ "Dune: Book to Screen Timeline" ~ DuneInfo.com

- ^ Chris Cutler, book included with Henry Cow 40th Anniversary CD box set (2008)

- ^ Falk, Gaby (ed). HR GIGER Arh+. Taschen, 2001, p.52

- ^ "The Film You Will Never See" by Alejando Jodorowsky ~ DuneInfo.com

- ^ Cinefantastique, September 1984 (Vol 14, No 4 & 5 - Double issue).

- ^ Dune/Alternate Versions ~ IMDb.com

- ^ Dune Resurection - Re-visiting Arrakis ~duneinfo.com

- ^ "David Lynch reveals his battle tactics" ~ CityofAbsurdity.com

- ^ The Dune Collectors Survival Guide ~ Arrakis.co.uk

- ^ "The 57th Academy Awards (1985) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. http://www.oscars.org/awards/academyawards/legacy/ceremony/57th-winners.html. Retrieved 2011-10-13.

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger (1984). "Movie Reviews: Dune (1984)". RogerEbert.SunTimes.com. http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/19840101/REVIEWS/401010332/1023. Retrieved March 14, 2010.

- ^ Cullum, Brett (February 13, 2006). "Review: Dune: Extended Edition". DVDVerdict.com. http://www.dvdverdict.com/reviews/duneextended.php. Retrieved March 14, 2010.

- ^ "Dune". At The Movies. December 1984.

- ^ "The Stinkers of 1984". At The Movies.

- ^ Dune: Retrospective, Extrovert magazine

- ^ Maslin, Janet (December 14, 1984). "Movie Review: Dune (1984)". The New York Times (Movies.NYTimes.com). http://movies.nytimes.com/movie/review?res=9F06E2D71238F937A25751C1A962948260. Retrieved March 15, 2010.

- ^ "Movie Review: Dune". Variety. January 1, 1984. http://www.variety.com/review/VE1117790608.html?categoryid=31&cs=1&p=0. Retrieved March 15, 2010.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (December 17, 1984). "Cinema: The Fantasy Film as Final Exam". Time. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,923850,00.html. Retrieved March 15, 2010.

- ^ Robin Wood. Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan. Columbia University Press, 1986. ISBN 9780231057776. Page 174.

- ^ Altman, Dennis. AIDS and the New Puritanism London: Pluto Press, 1986, p. 21

- ^ "Dune: Its name is a Killing Word" ~ ErasingClouds.com Retrieved June 12, 2010.

- ^ Dune (1984) ~ RottenTomatoes.com

- ^ Dune (1984) ~ Yahoo! Movies

- ^ "Visionary and dreamer: A surrealist's fantasies" ~ 1984 David Lynch interview ~ DavidLynch.de

- ^ Dune: Retrospective, Extrovert magazine

- ^ Star Wars Origins: Dune ~ Moongadget.com

- ^ Herbert, Frank (1985). "Introduction". Eye. ISBN 0-425-08398-5.

External links

- Dune at the Internet Movie Database

- Dune at AllRovi

- Dune at Rotten Tomatoes

- Dune at Box Office Mojo

The extended Dune series of fictional works Original series- Dune (1965)

- Dune Messiah (1969)

- Children of Dune (1976)

- God Emperor of Dune (1981)

- Heretics of Dune (1984)

- Chapterhouse: Dune (1985)

- Dune: House Atreides (1999)

- Dune: House Harkonnen (2000)

- Dune: House Corrino (2001)

- Dune: The Butlerian Jihad (2002)

- Dune: The Machine Crusade (2003)

- Dune: The Battle of Corrin (2004)

Dune sequels- Hunters of Dune (2006)

- Sandworms of Dune (2007)

- Paul of Dune (2008)

- The Winds of Dune (2009)

Great Schools of Dune- The Sisterhood of Dune (forthcoming)

OtherFilm adaptations- Dune (1984) (soundtrack)

- Frank Herbert's Dune (2000)

- Frank Herbert's Children of Dune (2003)

GamesCompanion books- The Dune Encyclopedia (1984)

- The Road to Dune (2005)

The works of David Lynch Feature films Eraserhead (1977) · The Elephant Man (1980) · Dune (1984) · Blue Velvet (1986) · Wild at Heart (1990) · Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me (1992) · Lost Highway (1997) · The Straight Story (1999) · Mulholland Drive (2001) · Inland Empire (2006)Short films Industrial Symphony No. 1 (1990) · Premonition Following An Evil Deed (1995) · Darkened Room (2002) · Boat (2007) · Absurda (2007) · Lady Blue Shanghai (2010)Television Other work Catching the Big Fish · Rabbits · Images · DumbLand · The Angriest Dog in the World · BlueBob · The Air Is on Fire · Lynch on Lynch · Surveillance · My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done? · Dark Night of the Soul · Crazy Clown TimeAwards by film The Elephant Man · Blue Velvet · Wild at HeartCategories:- 1984 films

- American films

- English-language films

- 1980s action films

- 1980s science fiction films

- American epic films

- American science fiction action films

- Dune on film and television

- Estudios Churubusco films

- Films directed by Alan Smithee

- Films directed by David Lynch

- Films shot anamorphically

- Science fiction war films

- Space adventure films

- Universal Pictures films

- Films shot in Mexico

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.