- Battle of Arawe

-

Battle of Arawe Part of World War II, Pacific War

U.S. Army soldiers land at AraweDate 15 December 1943–24 February 1944 Location Arawe, New Britain, Territory of New Guinea

6°10′S 149°1′E / 6.167°S 149.017°ECoordinates: 6°10′S 149°1′E / 6.167°S 149.017°EResult Allied victory Belligerents  United States

United States

Australia

Australia Empire of Japan

Empire of JapanCommanders and leaders Brig. Gen. Julian W. Cunningham Major Masamitsu Komori Strength Approx. 5000 Approx. 634 Casualties and losses 118 killed

352 wounded

4 missing304 killed

4 captured[1]Arawe – Cape Gloucester – Talasea – Gasmata – Jacquinot Bay – Wide Bay – Open BayThe Battle of Arawe was a battle during the New Britain Campaign of World War II. This campaign formed part of Operation Cartwheel and had the objective of isolating the key Japanese base at Rabaul. Arawe was attacked on 15 December 1943 by U.S. and Australian forces to secure an advanced base on the southern coast of New Britain and was secured after a month of fighting.

Contents

Background

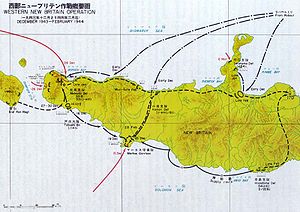

In June 1943, the Allies launched a major offensive—designated Operation Cartwheel—aimed at capturing the major Japanese base at Rabaul on the eastern tip of New Britain. During the next five months, Australian and U.S. forces—under the overall command of General Douglas MacArthur—advanced along the north coast of eastern New Guinea, capturing Lae and the Huon Peninsula in September. U.S. forces under the command of Admiral William Halsey, Jr. simultaneously advanced through the Solomon Islands from Guadalcanal and established an air base at Bougainville in November.[2] Plans for Operation Cartwheel were amended in August 1943 when the British and United States Combined Chiefs of Staff approved the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff's proposal that Rabaul be isolated rather than captured.[3]

The Japanese Imperial General Headquarters assessed the strategic situation in the South-West Pacific in late September 1943 and concluded that the Allies would attempt to break through the northern Solomon Islands and Bismark Archipelago in the coming months en route to Japan's inner perimeter in the western and central pacific. Accordingly, reinforcements were dispatched to strategic locations in the area in an attempt to slow the Allied advance. Strong forces were retained at Rabaul, however, as it was believed that the Allies would attack the town. At the time Japanese positions in western New Britain were limited to airfields at Cape Gloucester on the island's western tip and several small way stations used by supply barges travelling between Rabaul and New Guinea.[4]

On 22 September 1943, General MacArthur's General Headquarters (GHQ) directed General Walter Krueger's Alamo Force to secure western New Britain and the surrounding islands. The goals of this operation were to establish air and PT boat bases which could be used to further reduce the Japanese forces at Rabaul and secure the straits between New Guinea and New Britain to allow convoys to pass through it en-route to operations along New Guinea's north coast and beyond. To this end, GHQ planned to capture Cape Gloucester at the western end of New Britain and Gasmata on the island's southern coast.[5] The veteran 1st Marine Division was selected for the Cape Gloucester operation.[6]

Senior Allied commanders disagreed over whether it was necessary to land forces in western New Britain. Major General George Kenney—commander of the Allied air forces in the South-West Pacific—opposed the landings, arguing that it was not necessary to establish an air base at Cape Gloucester as the existing bases in New Guinea and surrounding islands were adequate to support the planned future landings in the region. Vice Admiral Arthur S. Carpender—commander of the 7th Fleet—and Rear Admiral Daniel E. Barbey—commander of the Task Force 76 (TF 76)—were in favor of securing Cape Gloucester to secure both sides of the straits, but opposed the landing at Gasmata as it was too close to the Japanese air bases at Rabaul. In response to Kenney and the Navy's concerns and intelligence reports that the Japanese had reinforced their garrison at Gasmata, the landing there was cancelled in early November.[7]

On 21 November, a conference between GHQ, Kenney, Carpender and Barbey was held in Brisbane at which it was decided to land a small force in the Arawe area to establish a PT boat base and create a diversion before the main landing at Cape Gloucester.[8] This landing had three goals; firstly to divert Japanese attention away from Cape Gloucester, secondly to establish a defensive perimeter and make contact with the marines once they landed and thirdly to establish a base for PT boats.[9] It was intended that PT boats operating from the base would disrupt Japanese barge traffic along the southern shore of New Britain and protect the Allied naval forces at Cape Gloucester from attack.[10]

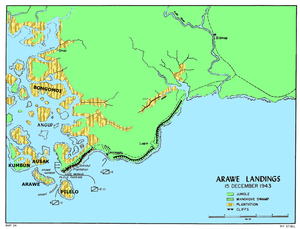

The Arawe area lies on the south coast of New Britain about 100 mi (87 nmi; 160 km) from the island's western tip. Its main geographical feature is Cape Merkus, which ends in the 'L'-shaped Arawe Peninsula. Several small islands called the Arawe islands lie to the south-west of the Cape. In late 1943, the Arawe Peninsula was covered by the Amalut Plantation and the terrain inland from the peninsula and on its offshore islands was swampy. Most of the shoreline in the area comprises limestone cliffs.[11] There was a small unused airfield 4 mi (6.4 km) east of the neck of the Arawe Peninsula and a coastal trail leading east from Cape Merkus to the Pulie River where it split into tracks running inland and along the coast. The terrain to the west of the peninsula was a trackless region of swamp and jungle which was very difficult for troops to move through.[12] Several of the beaches in the area were suitable for landing craft; the best were House Fireman on the peninsula's west coast and the village of Umtingaulu to the east of the peninsula's base.[13]

Prelude

Planning

Alamo Force was responsible for coordinating plans for the invasion of western New Britain. The Arawe landing was scheduled for 15 December, as this was the earliest date by which the air bases needed to support the landing would be operational and allowed time for the landing force to conduct necessary training and rehearsals.[14] As Arawe was believed to be only weakly defended, Krueger decided to use a smaller force than that which had been selected for the landing at Gasmata.[6] This force—which was designated the Director Task Force—was concentrated at Goodenough Island where it was stripped of all equipment not needed for combat operations. Logistical plans called for the assault echelon to carry 30 days worth of general supplies and enough ammunition for three days of intensive combat. After the landing holdings would be expanded to 60 days of general supplies and six days worth of all categories of ammunition other than anti-aircraft ammunition, for which a 10-day supply was thought necessary.[15] The assault force and its supplies were to be carried in fast ships which could rapidly unload their cargo and leave the area.[16]

The commander of the PT boat force in the South-West Pacific, Morton C. Mumma, opposed establishing a PT boat base at Arawe, as he had sufficient bases and Japanese barges normally sailed along the north coast of New Britain. He took his concerns to Carpender and Barbey who eventually agreed that he would not be required to establish a base there if he thought it unnecessary.[10] Instead, he assigned six boats from bases at Dreger Harbor in New Guinea and Kiriwina Island island to operate along the south coast of New Britain east of Arawe each night and asked for only emergency refueling facilities to be established at Arawe.[17]

The Director Task Force's commander—Brigadier General Julian W. Cunningham—issued the orders for the landing on 4 December. Under these plans, the force was to secure the Arawe Peninsula and surrounding islands and establish an outpost on the trail leading to the Pulie River. Once the beachhead was secure, amphibious patrols would be conducted to the west of the peninsula to attempt to make contact with the marines at Cape Gloucester. Two subsidiary landings were planned to take place one hour before dawn and before the main body of the Director Task Force landed at House Fireman Beach on the Arawe Peninsula. One landing would capture Pitoe Island to the Peninsula's south as it was believed that the Japanese had established a radio station and defensive position there which commanded the entrance to Arawe Harbor. The other landing was to be made at Umtingalu to establish a blocking position on the coastal trail east of the peninsula.[18] U.S. Navy members of the planning staff were concerned about the subsidiary landings as a nighttime landing conducted at Lae in September had proven difficult.[19]

Opposing forces

Main article: Battle of Arawe order of battleThe Director Task Force was centered around the U.S. Army's 112th Cavalry Regimental Combat Team. This regiment had arrived in the Pacific in August 1942 but had not seen combat. It was dismounted and converted to an infantry unit in May 1943 and undertook an unopposed landing at Woodlark Island on 23 June.[20] The 112th Cavalry Regiment was smaller and more lightly armed than U.S. infantry regiments and had only two battalion-sized squadrons compared to the three battalions in infantry regiments.[21] The 112th RCT's combat support units were the M2A1 howitzer-equipped 148th Field Artillery battalion and the 59th Engineer Company. The other combat units of the Director Task Force were the 236th Antiaircraft Artillery Battalion (Searchlight) less elements, two batteries of the 470th Antiaircraft Artillery Battalion (Automatic Weapons), A Company, 1st Amphibious Tractor Battalion and a detachment from the 26th Quartermaster War Dog Platoon.[22] The 2nd Battalion of the 158th Infantry Regiment was held in reserve to reinforce the Director Task Force if required. Several engineer, medical, ordnance and other support units were scheduled to arrive at Arawe after the landing was completed.[6] Cunningham requested that an 90 mm (3.54 in) anti-aircraft gun-equipped battery be added to the force, but none were available.[17] The U.S. Navy's Beach Party Number 1 also landed with the Director Task Force and was withdrawn once the beachhead was secure.[23]

The Director Task Force was supported by Allied naval and air units. The naval force was drawn from TF 76 and comprised U.S. Navy destroyers USS Conyngham (Barbey's flagship), Shaw, Drayton, Bagley, Reid, Smith, Lamson, Flusser and Mahan, a transport group with destroyer transports USS Humphreys and Sands, transport ships HMAS Westralia and USS Carter Hall, two patrol craft and two submarine chasers and a service group with three LSTs, three tugboats and the destroyer tender USS Rigel.[24][25] USAAF and RAAF units operating under the Fifth Air Force would support the landing but only limited air support was to be available after 15 December.[26] Parties of Australian Coastwatchers on New Britain were also reinforced during September 1943 to provide warning of air attacks from Rabaul bound for the Allied landing sites.[27]

At the time of the Allied landing, Arawe was defended by only a small force, though reinforcements were en route. The Japanese force at Arawe comprised 120 soldiers and sailors organised in two temporary companies drawn from the 51st Division.[28] The reinforcing units were elements of the 17th Division, which had been shipped from China to Rabaul during October 1943 to reinforce western New Britain ahead of the expected Allied invasion. The convoys carrying the division were attacked by U.S. Navy submarines and USAAF bombers, resulting in 1,173 of its men being killed or wounded. The 1st Battalion, 81st Infantry Regiment was assigned to defend Cape Merkus but didn't depart Rabaul until December, as it needed to be reorganised after suffering casualties when the ship it was travelling on from China was sunk. In addition, two of its rifle companies, most of its heavy machine guns and all its 70 mm (2.76 in) howitzers were retained by the 8th Area Army at Rabaul, leaving the battalion with a strength of just its headquarters, two rifle companies and a machine gun platoon. This battalion—which came under the command of Major Masamitsu Komori—was a four-day march from Arawe when the Allies landed.[29] A company from the 54th Infantry Regiment, some engineers and detachments from other units were also assigned to the Arawe area. The ground forces at Arawe came under the command of General Matsuda, whose headquarters were located near Cape Goucester.[30] The Japanese air units at Rabaul had been greatly weakened in the months prior to the landing at Arawe by prolonged Allied attacks and the transfer of the 7th Air Division to western New Guinea.[31] Nevertheless, the Japanese 11th Air Fleet had 100 fighters and 50 bombers based at Rabaul at the time of the landing at Arawe.[32]

Preliminary operations

The Allies possessed little intelligence on western New Britain's terrain and the exact location of Japanese forces. To rectify this, Allied aircraft conducted extensive air photography and small ground patrols were landed by PT boats.[33] A small team from Special Service Unit No. 1 reconnoitered Arawe on the night of 9/10 December and concluded that there were few Japanese troops in the area.[6][34] This party was detected near the village of Umtingalu, leading the Japanese to strengthen their defenses there.[35]

The Allied air forces began pre-invasion attacks on western New Britain on 13 November. Few attacks were made on the Arawe area, however, in an attempt to achieve tactical surprise. Instead, heavy attacks were made against Gasmata, Ring Ring Plantation, and Lindenhafen Plantation. The Arawe area was struck for the first time on 6 December and again on 8 December; little opposition was encountered on either occasion. It was not until 14 December—the day before the landing—that heavy air attacks on Arawe were conducted. On this day, Allied aircraft flew 273 sorties against targets on New Britain's south coast.[36]

The Director Task Force was concentrated at Goodenough Island in early December 1943. A full-scale rehearsal of the landing was held there which revealed problems with coordinating the waves of boats and demonstrated that some of the force's officers lacked confidence in conducting amphibious operations. There was not sufficient time to conduct further training to rectify these problems, however.[17] The Task Force embarked onto transport ships during the afternoon of 13 December, and the convoy sailed at midnight. It proceeded to Buna to rendezvous with most of the escorting destroyers and made a feint towards Finschhafen before turning towards Arawe after dusk on 14 December. The convoy was detected by a Japanese aircraft shortly before it anchored off Arawe at 03:30 on 15 December, and the Japanese 11th Air Fleet at Rabaul began to prepare aircraft to attack it.[25][37]

Battle

Landings

Shortly after the assault convoy arrived off Arawe Carter Hall launched her LVTs and Westralia her landing craft. The two large transports departed for New Guinea at 05:00. The APDs carrying Troops A and B of the 112th Cavalry Regiment closed to within 1,000 yd (910 m) of Umtingalu and Pilelo island and unloaded the soldiers in rubber boats.[37]

A Troop's attempt to land at Umtingalu was unsuccessful. At about 05:25, the troop came under fire from machine guns, rifles and a 25 mm (0.98 in) cannon as it was nearing the shore, and all but three of its 15 rubber boats were sunk.[38] Shaw—the destroyer assigned to support the landing—was unable to provide supporting fire until 05:42 as she initially couldn't determine if the soldiers in the water were in her line of fire; once she had a clear shot, she silenced the Japanese positions with two salvos from her 5 in (130 mm) guns.[39] The surviving cavalrymen were rescued by small boats and later landed at House Fireman beach; casualties were 12 killed, four missing and 17 wounded.[40] The troop lost all of its equipment during the landing attempt, and replacement equipment was air dropped into the beachhead during the afternoon of 16 December.[41]

B Troop's landing at Pilelo island was successful. The goal of this operation was to destroy a Japanese radio station believed to be at the village of Paligmete on the island's east coast. While the troop originally intended to make a surprise landing at Paligmete, it switched to the island's west coast after A Troop came under attack. Once ashore the cavalrymen advanced across the island, coming under fire from a small Japanese force at the village of Winguru. After finding Paligmete unoccupied B Troop attacked Winguru, and used bazookas and flamethrowers to destroy the Japanese positions there. One American and seven Japanese were killed in this fighting.[40]

The 2nd Squadron, 112th Cavalry Regiment made the main landing at House Fireman Beach. The landing was delayed by difficulties forming the LVTs into an assault formation and a strong current, and the first wave landed at 07:28 rather than 06:30 as planned. Destroyers bombarded the beach with 1,800 rounds of 5 in ammunition between 06:10 and 06:25 and B-25 Mitchells strafed the area once the bombardment concluded. The delays meant that landing area was not under fire as the troops approached the beach, and Japanese machine gunners fired on the LVTs; these were rapidly silenced by rockets fired from SC-742 and two DUKWs. The first wave was fortunate to meet little opposition as there were further delays in landing the follow-up waves due to differences in the speeds of the two types of LVTs used. While the four follow-up waves were scheduled to land at five minute intervals after the first wave, the second wave landed 25 minutes after the initial force and the succeeding three waves landed simultaneously 15 minutes later.[42][43] Within two hours of the landing all the large Allied ships other than Barbey's flagship had departed from Arawe. Conyngham remained in the area to rescue survivors of the landing at Umtingalu and withdraw later that day.[44]

Once ashore, the cavalrymen rapidly secured the Arawe Peninsula. A patrol sent to the peninsula's toe met only scattered resistance from Japanese rear guards. Over 20 Japanese were located in a cave on the east side of the peninsula, and these were killed by E Company and personnel from the Squadron Headquarters. The remaining Japanese units in the area retreated to the east. As a result, the 2nd Squadron reached the peninsula's base in the mid afternoon of Z-Day and began to prepare its Main Line of Resistance (MLR) there.[45] By the end of the day over 1,600 Allied troops were ashore.[32]

The naval force off Arawe was subjected to a heavy air raid shortly after the landing. At 09:00, eight Aichi D3A2 "Val" dive bombers escorted by 56 A6M5 Zero fighters evaded the USAAF combat air patrol (CAP) of 16 P-38 Lightnings. The Japanese force attacked the recently-arrived first supply echelon, which comprised five LCTs and 14 LCMs, but these ships managed to evade the bombs dropped on them.[46] While the first wave of attackers suffered no losses, at 11:15 four P-38s shot down a Zero and at 18:00 a force of 30 Zeros and 12 Mitsubishi G4M3 "Betty" and Mitsubishi Ki-21-II "Sally" bombers was also driven off by four P-38s.[47]

Air attacks and base development

While the U.S. ground troops faced no opposition in the days immediately after the landing, the naval convoys carrying reinforcements to the area were repeatedly attacked.[32] The second supply echelon came under continuous air attack on 16 December, resulting in the loss of APc-21, damage to SC-743, YMS-50 and four LCTs and about 42 men killed or seriously wounded. Another reinforcement convoy was attacked three times by dive bombers on 21 December as it unloaded. Further air attacks took place on 26, 27 and 31 December.[48] Between 15 and 31 December, at least 24 Japanese bombers and 32 fighters were shot down in the Arawe area.[47] The process of unloading ships at Arawe was hampered by air attacks, the beach party being too small and inexperienced and congestion on House Fireman Beach. The resultant delays in unloading LCTs caused some to leave the area before discharging all their cargo.[49]

Air attacks on Arawe dropped off after 1 January. From this date most attacks took place at night, and few occurred after 90 mm anti-aircraft guns were established at Arawe on 1 February.[50] These weak attacks did not disrupt the Allied convoys.[48] In the three weeks after the landing, 6,287 short tons (5,703 t) of supplies and 541 guns and vehicles were transported to Arawe.[48] The 3rd Squadron, 112th Cavalry Regiment was transported to Arawe from Goodenough Island on 18 December; the cavalry regiment and its attached artillery battalion were thought to be sufficient to defend Arawe against any counter-attacks.[51]

Following the landing, the 59th Engineer Company constructed logistics facilities in the Arawe area. In response to the Japanese air raids priority was given to the construction of a partiarly underground evacuation hospital, and it was completed in January 1944. The underground hospital was replaced with a 120-bed above-ground facility in April 1944. Pilelo Island was selected for the site of the PT boat facilities, and a pier for refuelling the boats and dispersed fuel storage bays were built there. A 172 ft (52 m) pier was also built at House Fireman Beach to accommodate small ships between 26 February and 22 April 1944; three LCT jetties were also constructed north of the beach. A 920 ft (280 m) by 100 ft (30 m) airstrip was hurriedly built for artillery observation aircraft on 13 January and this was later upgraded and surfaced with coral. The engineer company also constructed 5 mi (8.0 km) of all-weather roads in the Arawe region and provided the Director Task Force with water via salt water distillation units on Pilelo Island and wells dug on the mainland. These projects were continuously hampered by shortages of construction materials, but the engineers were able to complete them though improvising and making use of salvaged material.[52]

Japanese response

The commander of the Japanese 17th Division—General Sakai—ordered that Arawe be urgently reinforced when he was informed of the landing there. The force under Major Komori was ordered to make haste and the 1st Battalion, 141st Infantry Regiment (less one company) was directed to move to Arawe by sea from Cape Bushing. Komori was designated the commander of all Japanese forces in the Arawe area. The 1st Battalion, 141st Infantry Regiment landed at the village of Omoi on the night of 18 December, and started overland the next day to join Komori's force at Didmop. Komori reached Didmop on 19 December and gathered the force which was retreating from Umtingalu under this command. The 1st Battalion, 141st Infantry Regiment took eight days to cover the 7 mi (11 km) between Omoi and Didmop, however, as it became lost repeatedly in the trackless jungle and paused whenever contact with American forces seemed likely.[51]

After establishing its beachhead on 15 December, the Director Task Force was reinforced and began patrols of the area. Cunningham had been ordered to gather intelligence on Japanese forces in western New Britain, and on 17 December he dispatched a patrol of cavalrymen mounted in two LCVPs to the west of Arawe to investigate the Itni River area. On 18 December, these landing craft encountered seven Japanese barges carrying part of the 1st Battalion, 141st Infantry Regiment near Cape Peiho, 20 mi (32 km) west of Arawe. After an exchange of gunfire the U.S. soldiers abandoned their landing craft and returned to Arawe along the coast.[51][53]

After organizing his force while waiting for the 1st Battalion, 141st Infantry Regiment for several days, Komori began his advance on Arawe on 24 December. He arrived at the airstrip to the north of Arawe during the early hours of Christmas Day and forced the 112th Cavalry Regiment's patrols back on Umtingalu, which was evacuated shortly thereafter. That night, the Japanese mounted a company-strength probing attack on the American main line of resistance which was repulsed with at least 12 Japanese killed.[54] The fighting to the west and north of Arawe led Cunningham to incorrectly believe that Komori's force was the advance guard of a large force dispatched from Gasmata. In response, he requested reinforcements from Krueger who dispatched G Company of the 158th Infantry Regiment to Arawe onboard PT boats.[53]

The Japanese offensive continued after the Christmas Day attack. Further attacks were made in the next few days, including daytime attacks on 28 and 29 December. All were repelled by American mortar fire, and most of Komori's initial force was killed during the attack on 29 December. The 1st Battalion, 141st Infantry Regiment arrived in the Arawe area on the afternoon off 29 December and conducted several small and unsuccessful attacks in early January 1944 before taking up positions about 400–500 yd (370–460 m) north of the American MLR. These positions comprised shallow trenches and foxholes which were difficult to see. While only about 100 Japanese soldiers were in the area, they moved their six machine guns frequently, making them difficult targets for American mortars and artillery.[53]

American counter attack

American patrols detected the Japanese defensive position on 31 December. Several attacks were made upon the area in the next few days, but without success. On 6 January 1944, Cunningham requested further reinforcements, including tanks to tackle the Japanese defenses. Krueger approved this request and ordered F Company, 158th Infantry Regiment and Company B of the USMC 1st Tank Battalion to Arawe; the two units arrived on 10 and 12 January respectively. The Marine tanks and two companies of the 158th Infantry Regiment subsequently practiced tank-infantry cooperation from 13 -15 January, while the 112th Cavalry continued to conduct patrols into Japanese-held areas.[55][56]

The Director Task Force launched its attack on 16 January. That morning a squadron of B-24 Liberators dropped one hundred thirty-six 1,000 lb (450 kg) bombs on the Japanese defenses, and 20 B-25s strafed the area. Following an intensive artillery and mortar barrage the Marine tank company, two companies of the 158th Infantry and C Troop, 112th Cavalry Regiment attacked. The tanks led the attack, with each being followed by a group of infantry or cavalrymen. The attack was successful and reached its objectives by 16:00. Once the objective was reached, Cunningham withdrew the force back to the MLR; during the withdrawal, two Marine tanks—which had become immobile—were destroyed to prevent the Japanese from using them as pillboxes.[56][57]

Following the American attack, Komori pulled his remaining forces back to defend the airstrip. As this was not an Allied objective, the Japanese force was not subjected to further attacks by ground troops beyond occasional patrol clashes and ambushes. They suffered from severe supply shortages, however, and many fell sick. Attempts to bring supplies in by sea from Gasmata were disrupted by U.S. Navy PT boats and the force lacked sufficient porters to supply itself through overland trails. Komori concluded that his force was serving no purpose, and on 8 February informed his superiors that it faced self-destruction due to supply shortages.[58] His commanders responded by ordering the force to hold its position, however, though it was awarded two Imperial citations in recognition of its supposed success in defending the airstrip.[59]

Aftermath

The 1st Marine Division's landing at Cape Gloucester on 26 December 1943 was successful. The marines secured the airfields which were the main objective of the operation on 29 December against only light Japanese opposition. Heavy fighting took place during the first two weeks of 1944, however, when the marines advanced south east of their initial beachhead to secure Borgen Bay. Little fighting took place once this area had been captured and the marines patrolled extensively in an attempt to locate the Japanese.[60] On 16 February, a marine patrol from Cape Gloucester made contact with an army patrol from Arawe at the village of Gilnit.[61] On 23 February, the remnants of the Japanese force at Cape Gloucester was ordered to withdraw to Rabaul.[62]

The Komori Force was eventually ordered to withdraw on 24 February as part of the general Japanese retreat from western New Britain. The Japanese immediately began to leave their positions, and headed north along inland trails to join other Japanese units. The Americans did not detect this withdrawal until 27 February, when an attack conducted by the 2nd Squadron, 112th Cavalry and Marine tank company to clear the Arawe area of Japanese encountered no opposition.[59] Major Komori fell behind his unit, and was killed on 9 April near San Remo on New Britain's north coast when he, his executive officer and two enlisted men they were travelling with were ambushed by a patrol from the 2nd Battalion 5th Marines.[63]

The original rationale for the Allied landings of creating a PT boat base was dropped before the operation commenced, and a base was never developed at Arawe.[64] Therefore, the U.S. attack on Arawe served only to divert the Japanese attention away from the larger landing at Cape Gloucester.[65] In this it was successful.

The 112th Cavalry Regiment remained at Arawe until late April 1944, when it was replaced by a reinforced battalion from the 40th Infantry Division.[66] By this time, the 112th Cavalry's strength had declined from 1,728 at the start of the battle to about 1,100 due to sickness and combat casualties.[67] The 40th Infantry Division battalion was in turn replaced by the Australian Army's 5th Division in late November 1944.[citation needed]

Notes

- ^ Krueger (1979), p. 381

- ^ Coakley (1989), pp. 510–511

- ^ Miller (1959), p. 225

- ^ Shaw and Kane (1963), pp. 324–325

- ^ Miller (1959), pp. 272–273

- ^ a b c d Miller (1959), p. 277

- ^ Miller (1959), pp. 273–274

- ^ Miller (1959), p. 274

- ^ Holzimmer (2007), p. 117

- ^ a b Morison (1958), p. 372

- ^ Rottman (2002), p. 186

- ^ Shaw and Kane (1963), p. 334

- ^ Miller (1959), p. 283

- ^ Miller (1959), pp. 274–275

- ^ Miller (1959), p. 279

- ^ Shaw and Kane (1963), p. 335

- ^ a b c Shaw and Kane (1963), p. 336

- ^ Shaw and Kane (1963), pp. 334–335

- ^ Barbey (1969), p. 101

- ^ Rottman (2009), pp. 21–22

- ^ Rottman (2009), p. 13

- ^ Rottman (2009), p. 24

- ^ Barbey (1969), pp. 103–104

- ^ Gill (1968), p. 338

- ^ a b Morison (1958), p. 374

- ^ Morison (1958), p. 373

- ^ Gill (1968), pp. 335–336

- ^ Shaw and Kane (1963), pp. 339–340

- ^ Shaw and Kane (1963), pp. 327–328

- ^ Miller (1959), p. 280

- ^ Miller (1959), pp. 281–282

- ^ a b c Miller (1959), p. 287

- ^ Miller (1959), pp. 276–277

- ^ Rottman (2005), p. 37

- ^ Morison (1958), pp. 374–375

- ^ Mortensen (1950), pp. 332–335

- ^ a b Shaw and Kane (1963), p. 338

- ^ Miller (1959), p. 284

- ^ Shaw and Kane (1963), pp. 338–339

- ^ a b Miller (1959), p. 285

- ^ Mortensen (1950), p. 335

- ^ Miller (1959), pp. 285–286

- ^ Shaw and Kane (1963), p. 339

- ^ Barbey (1969), pp. 106–107

- ^ Miller (1959), pp. 286–287

- ^ Morison (1958), p. 376

- ^ a b Mortensen (1950), p. 336

- ^ a b c Morison (1958), p. 377

- ^ Shaw and Kane (1963), pp. 340–342

- ^ Mortensen (1950), p. 337

- ^ a b c Shaw and Kane (1963), p. 342

- ^ Office of the Chief Engineer, General Headquarters Army Forces, Pacific (1951), p. 192

- ^ a b c Miller (1959), p. 288

- ^ Shaw and Kane (1963), p. 343

- ^ Shaw and Kane (1963), p. 392

- ^ a b Miller (1959), p. 289

- ^ Shaw and Kane (1963), pp. 392–393

- ^ Shaw and Kane (1963), p. 393

- ^ a b Shaw and Kane (1963), p. 394

- ^ Miller (1959), pp. 289–294

- ^ Shaw and Kane (1963), p. 403

- ^ Miller (1959), p. 294

- ^ Shaw and Kane (1963), p. 427

- ^ Miller (1959). Page 289.

- ^ Morison (1958). Page 377.

- ^ "Combat Chronicle of the 40th Infantry Division". United States Army Center of Military History. http://www.history.army.mil/html/forcestruc/cbtchron/cc/040id.htm.

- ^ Drea (1984)

References

- Barbey, Daniel E. (1969). MacArthur's Amphibious Navy: Seventh Amphibious Force Operations 1943-1945. Annapolis: United States Naval Institute.

- Coakley, Robert W. (1989). "World War II: The War Against Japan". American Military History. Army Historical Series (Online ed.). Washington D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. http://www.history.army.mil/BOOKS/amh/AMH-23.htm.

- Drea, Edward J. (1984). "Defending the Driniumor: Covering Force Operations in New Guinea, 1944". Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: Combat Studies Institute U.S. Army Command and General Staff College. http://www-cgsc.army.mil/carl/resources/csi/Drea/Drea.asp. Retrieved 21 November 2009.

- Drea, Edward J. (1992). MacArthur's Ultra: Codebreaking and the War against Japan, 1942-1945. Modern War Studies. Lawrence: University of Kansas Press. ISBN 07000605762.

- Gill, G. Hermon (1968). Royal Australian Navy 1942–1945. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Series 2 – Navy. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. http://www.awm.gov.au/histories/second_world_war/volume.asp?levelID=67911.

- Hirrel, Leo (1995). Bismarck Archipelago. U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II. Washington D.C.: United States Army Center Of Military History. ISBN 016042089X. http://www.history.army.mil/brochures/bismarck/bismarck.htm.

- Holzimmer, Kevin C. (2007). General Walter Krueger. Unsung Hero of the Pacific War. Modern War Studies. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 9780700615001.

- Hough, Frank O., and John A. Crown (1952). "The Campaign on New Britain". USMC Historical Monograph. Historical Division, Division of Public Information, Headquarters U.S. Marine Corps. http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USMC/USMC-M-NBrit/index.html. Retrieved 2006-12-04.

- Japanese Demobilization Bureaux (1966). Charles A. Willoughby (editor in chief). ed. Japanese Operations in the Southwest Pacific Area Volume II - Part I. Reports of General MacArthur. Washington DC: United States Army Center of Military History. http://www.history.army.mil/books/wwii/MacArthur%20Reports/MacArthur%20V2%20P1/macarthurv2.htm.

- Krueger, Walter (1979) [1953]. From Down Under to Nippon. The Story of Sixth Army in World War II. Washington: Combat Forces Press. ISBN 0892010460.

- Long, Gavin (1963). The Final Campaigns. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Series 1 – Army. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. http://www.awm.gov.au/histories/second_world_war/volume.asp?levelID=67909.

- Miller, John, Jr. (1959). "CARTWHEEL: The Reduction of Rabaul". United States Army in World War II: The War in the Pacific. Office of the Chief of Military History, U.S. Department of the Army. http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USA/USA-P-Rabaul/index.html. Retrieved October 20, 2006.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1958). Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, vol. 6 of History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Castle Books. ISBN 0785813071.

- Mortensen, Bernhardt L. (1950). "Rabaul and Cape Gloucester". In Craven, Wesley Frank and Cate, James Lea. Vol. IV, The Pacific: Guadalcanal to Saipan, August 1942 to July 1944. The Army Air Forces in World War II. Washington D.C.: U.S. Office of Air Force History. ISBN 091279903X. http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/AAF/IV/index.html.

- Odgers, George (1968 (reprint)). Air War Against Japan 1943–1945. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Series 3 – Air. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. http://www.awm.gov.au/histories/second_world_war/volume.asp?levelID=67913.

- Powell, James Scott (2006). "Learning Under Fire: A Combat Unit in the Southwest Pacific". PhD Dissertation. College Station: Texas A&M University. http://txspace.tamu.edu/bitstream/handle/1969.1/4237/etd-tamu-2006B-HIST-Powell-Copyright.pdf?sequence=1. Retrieved 28 November 2009.

- Rottman, Gordon (2002). World War II Pacific Island Guide. A Geo-Military Study. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0313313954. http://books.google.com.au/books?id=ChyilRml0hcC&lr=&source=gbs_navlinks_s.

- Rottman, Gordon (2002a). U.S. Marine Corps World War II Order of Battle: Ground and Air Units in the Pacific War, 1939-1945. Westport: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0313319065.

- Rottman, Gordon (2005). US Special Warfare Units in the Pacific Theatre 1941–45. Battle Orders. Botley: Osprey. ISBN 1841767077.

- Rottman, Gordon (2009). World War II US Cavalry Units. Pacific Theater. Botley: Ospery Publishing. ISBN 9781846034510.

- Shaw, Henry I.; Douglas T. Kane (1963). "Volume II: Isolation of Rabaul". History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II. http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USMC/II/index.html. Retrieved 2006-10-18.

Categories:- 1943 in Papua New Guinea

- Conflicts in 1943

- New Britain

- Battles and operations of World War II involving Papua New Guinea

- Battles of World War II involving Japan

- Battles of World War II involving the United States

- South West Pacific theatre of World War II

- Battles of World War II involving Australia

- United States Marine Corps in World War II

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.