- Jus soli

-

Jus soli (Latin: right of the soil),[1] also known as birthright citizenship, is a right by which nationality or citizenship can be recognized to any individual born in the territory of the related state.[2] At the turn of the nineteenth century, nation-states commonly divided themselves between those granting nationality on the grounds of jus soli (France, for example) and those granting it on the grounds of jus sanguinis (right of blood) (Germany, for example, before 1990). However, most European countries chose the German concept of an "objective nationality", based on word, race or language (as in Fichte's classical definition of a nation), opposing themselves to republican Ernest Renan's "subjective nationality", based on a daily plebiscite of one's belonging to one's Fatherland. This non-essentialist concept of nationality allowed the implementation of jus soli, against the essentialist jus sanguinis. However, today's increase of migrants has somewhat blurred the lines between these two antagonistic sources of right.

Countries that have acceded to the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness will grant nationality to otherwise stateless persons who were born on their territory, or on a ship or plane flagged by that country.

Contents

History

At one time, Jus sanguinis was the sole means of determining nationality in Europe (where it is still widespread in Central and Eastern Europe) and Asia. An individual belonged to a family, a tribe or a people, not to a territory. It was a basic tenet of Roman law.[3]

An early form of partial jus soli dates from the Cleisthenes' reforms, and developed further in the Roman world where citizenship was extended to all free inhabitants of the Empire, especially with the Constitutio Antoniniana (Edict of Caracalla).[3]

But it was much later, with the independence of the English colonies in America, and the French Revolution, that laid the foundations for jus soli. With the social and economic development of the 19th and 20th centuries, and above all, the massive migrations to the Americas and Western Europe, that jus soli was established in a greater and greater number of countries.[3]

The geographer Jared Diamond has calculated that if the application of jus soli since 1850 were abolished, 60% of Americans and 80% of Argentinians would lose their citizenship, and 25% of British and French.[3]

Lex soli

Lex soli is a law used in practice to regulate who and under what circumstances an individual can assert the right of jus soli. Most states provide a specific lex soli, in application of the respective jus soli, and it is the most common means of acquiring nationality. A frequent exception to lex soli is imposed when a child was born to a parent in the diplomatic or consular service of another state, on a mission to the state in question.[4]

Blurred lines between jus soli and jus sanguinis

There is a trend in some countries toward restricting lex soli by requiring that at least one of the child's parents be a national of the state in question at the child's birth, or a legal permanent resident of the territory of the state in question at the child's birth.[5]

Specific national legislation

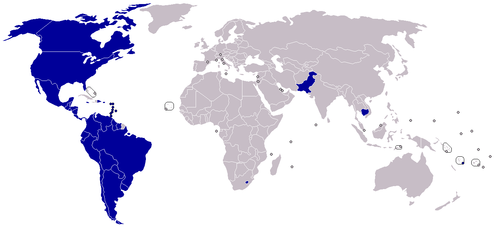

Jus soli is observed by less than 20% of the world's countries. Of advanced economies, Canada and the United States are the only countries that grant automatic citizenship to children born to illegal aliens. No European country grants automatic citizenship to children of illegal aliens.[6]

States that observe jus soli include:

- Antigua and Barbuda[7]

- Argentina[7]

- Barbados[7]

- Belize[7]

- Bolivia[7]

- Brazil[7]

- Cambodia[7]

- Canada[7]

- Chile[8] (children of transient foreigners or of foreign diplomats on assignment in Chile only upon request)

- Colombia[7]

- Costa Rica[7]

- Dominica[7]

- Ecuador[7]

- El Salvador[7]

- Fiji[9]

- Grenada[7]

- Guatemala[7]

- Guyana[7]

- Honduras[7]

- Jamaica[7]

- Lesotho[10]

- Mexico[7]

- Nicaragua[7]

- Pakistan[7]

- Panama[7]

- Paraguay[7]

- Peru[7]

- Saint Christopher and Nevis[7]

- Saint Lucia[7]

- Saint Vincent and the Grenadines[7]

- Trinidad and Tobago[7]

- United States[7]

- Uruguay[7]

- Venezuela[7]

In contacting foreign governments directly, the Center for Immigration Studies was able to confirm that only 33 of the world's 194 countries grant automatic birthright citizenship to children born to illegal aliens. Some countries which do have such automatic birthright citizenship policies rarely grant such citizenship to children of illegal aliens, however.[6]

Modification of jus soli

In a number of countries automatic birthright citizenship has been effectively repealed by imposing additional requirements (such as having at least one of the parent's being a legal permanent resident or requiring that the parent have resided in the country for a specific period of time).[6] As a result, the children illegal immigrants do not have automatic citizenship conferred upon their birth. Jus soli has been changed in the following countries:[11]

- United Kingdom on 1 January 1983 - requiring that one parent be a British citizen or be legally "settled" in the country (see British nationality law)).

- Australia on 20 August 1986[5] - the law was changed to require that a person born in Australia acquired Australian citizenship by birth only if at least one parent was an Australian citizen or permanent resident; or upon the 10th birthday of a child born in Australia regardless of their parent's citizenship status (see Australian nationality law)

- Republic of Ireland on 1 January 2005 - requiring that at at least one of the parent's be an Irish citizen; a British citizen; a child of a resident with a permanent right to reside in Ireland; or be a child of a legal resident residing three of the last four years in the country (excluding students and asylum seekers)(see Irish nationality law).[5]

- New Zealand on 1 January 2006[5] - the law was changed in 2006 requiring that at least one of the parents be a New Zealand citizen or permanent resident in order to confer citizenship (see New Zealand nationality law)[12]

- South Africa on 6 October 1995[5] - Children born in South Africa to South African citizens or permanent residents are automatically granted South African citizenship (see South African nationality law).

- France - Children born in France (including overseas territories) to at least one parent who is also born in France automatically acquire French citizenship at birth. Children born to foreign parents may request citizenship depending on their age and length of residence (see French nationality law).

- Dominican Republic on 26 January 2010 - the Dominican Republic formally amended its constitution to effectively exclude Dominicans of Haitian origin from citizenship even those who were previously recognized by the Dominican state. The new constitution broadened the definition of the 2004 migration law to exclude individuals that were “in transit” to include “non-residents” (including individuals with expired residency visas and undocumented workers).[13][14]

- Germany on 1 January 2000 - One exception to the increasing restrictiveness toward birthright citizenship has been Germany. Prior to 2000, German nationality law was based entirely on jus sanguinis. Now children born on or after 1 January 2000 to non-German parents acquire German citizenship at birth if at least one parent has a permanent residence permit (and has had this status for at least three years); and the parent has been residing in Germany for at least eight years.

Modification of jus soli has been criticized as contributing to economic inequality, the perpetuation of unfree labour from a helot underclass,[5] and statelessness.

Abolition of jus soli

Some countries which formerly operated jus soli have moved to abolish it entirely, only conferring citizenship on children born in the country if one of the parents is a citizen of that country. India did this on 3 December 2004, in reaction to illegal immigration from its neighbor Bangladesh, though jus soli was progressively weakened since 1987.[15] Malta also changed the principle of citizen to jus sanguinis on 1 August 1989, in a move that also relaxed restrictions against multiple citizenship.[16]

United States

The 14th Amendment to the United States Constitution reads, in pertinent part, "All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside." Its wording was initially interpreted to exclude Native Americans because they were not considered "subject to the jurisdiction" of the United States and, thus, were not American citizens. Congress declared it policy to extend citizenship to all Aboriginal peoples in the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924.[17] In the 1898 case United States v. Wong Kim Ark 169 U.S. 649 (1898), the U.S. Supreme Court held that the "subject to the jurisdiction thereof" restriction applied only to two additional categories: children born to foreign diplomats and children born to enemy forces engaged in hostile occupation of the country's territory. The Court also rejected the government's attempt to limit Section 1 of the 14th Amendment by arguing it was intended solely to allow former slaves and their descendants to become citizens. The Court thus held that the petitioner, a child of subjects of the Emperor of China whose parents were lawfully living in the United States where he was born, was a U.S. citizen by birth. Notwithstanding the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, his citizenship status could not be revoked even if his parents were not American citizens at the time of his birth and all three made several trips to China afterwards.[18]

The Pew Hispanic Center determined that according to an analysis of Census Bureau data, about 8 percent of children born in the United States in 2008 (about 340,000) were offspring of unauthorized immigrants, with a total of 4 million U.S.-born children of unauthorized immigrant parents residing in the country in 2009.[19] Citing their numbers and concerns over "anchor babies", some lawmakers and activists have proposed abolishing jus soli in the United States.[5][20] Other commentators have argued that the Supreme Court's interpretation of the 14th Amendment was incorrect, and should be narrowed to only establishing the civil rights, privileges and immunities of the freed slaves.[21]

Hong Kong

A modified form of jus soli is provided by the Basic Law of Hong Kong. According to Article 24(1) of the Basic Law of the territory, in force since the July 1997 transfer of sovereignty over Hong Kong, all citizens of the People's Republic of China born in the territory are permanent residents of the territory and have the right of abode in Hong Kong. Furthermore, according to Article 24(5) of the same law, non-citizens born to non-citizen permanent resident parents in Hong Kong also receive permanent residence at birth. Other persons must "ordinarily reside" in Hong Kong for seven continuous years in order to gain permanent residence (Articles 24(2) and 24(5)).[22] In Hong Kong, most political rights and eligibility for most welfare benefits are conferred to permanent residents regardless of citizenship; conversely, PRC citizens who are not permanent residents (such as residents of mainland China and Macau) are not conferred these rights and privileges.

Hong Kong's Immigration Ordinance initially restricted the application of Article 24(1) to babies whose parents had the right of abode at the time of the baby's birth. However, the Court of Final Appeal struck down this portion of the Immigration Ordinance in the 2001 case Director of Immigration v. Chong Fung Yuen.[23] As a consequence, many women from mainland China began coming to Hong Kong to give birth; by 2008, the number of babies in the territory born to mainland mothers had grown to twenty-five times the number five years prior.[24][25]

See also

- Anchor baby

- Birth tourism

- Jus sanguinis

- Nationality law

- Native-born citizen

- Natural-born citizen – a specific requirement for the office of President of the United States

- Stateless person

References

- ^ jus soli, definition from merriam-webster.com.

- ^ Vincent, Andrew (2002). Nationalism and particularity. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b c d w:fr:Droit du sol

- ^ Guimezanes, Nicole. "What Laws for Naturalisation?" The OECD Observer. Paris: Jun/Jul 1994. , Iss. 188; pg. 24, 3 pgs (Cites legislation for Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada , Denmark, Finland, France, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, United Kingdom and the United States)

- ^ a b c d e f g Mancini, JoAnne; Finlay, Graham (September 2008). "'Citizenship Matters': Lessons from the Irish citizenship referendum". American Quarterly (American Quarterly) 60 (3): 575–599. doi:10.1353/aq.0.0034.

- ^ a b c Feere, Jon (2010). "Birthright Citizenship in the United States: A Global Comparison". Center for Immigration Studies. http://cis.org/birthright-citizenship.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae "Nations Granting Birthright Citizenship". NumbersUSA. http://www.numbersusa.com/content/learn/issues/birthright-citizenship/nations-granting-birthright-citizenship.html. Retrieved 6 September 2009.

- ^ Constitution of the Republic of Chile, chap. II, art. 10, par. 1 (Spanish text; English version without recent changes)

- ^ Fiji Constitution, chap. 3, sec. 10

- ^ The Constitution of Lesotho, chap. IV, sec. 38

- ^ NumbersUSA: "Nations Granting Birthright Citizenship" retrieved October 22, 2011

- ^ New Zealand Visa Bureau: "1000 kids face deportation or being orphaned for breaching New Zealand visa rules" October 7, 2011

- ^ Human Rights Brief: "The Constitution and the Right to Nationality in the Dominican Republic" October 29, 2010

- ^ Soros.org: "Deprivation of Citizenship for Dominicans of Haitian Descent" retrieved October 22, 2011

- ^ Sadiq, Kamal (2008). Paper Citizens: How Illegal Immigrants Acquire Citizenship in Developing Countries. Oxford University Press. p. 10. ISBN 9780195371222.

- ^ Bauböck, Rainer; Bernhard Perchinig, Wiebke Sievers (2007). Citizenship policies in the new Europe. Amsterdam University Press. p. 247. ISBN 9789053569221.

- ^ Schultz, Jeffrey D. (2000). Encyclopedia of Minorities in American Politics: Hispanic Americans and Native Americans. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 621. ISBN 9781573561495.

- ^ Ryan, John M. (27 August 2009). "Letters: U.S. citizenship". Silver City Sun-News. http://www.scsun-news.com/ci_13217786. Retrieved 6 September 2009.

- ^ Pew Hispanic Center: "Unauthorized Immigrants and Their U.S.-Born Children" August 11, 2010

- ^ "GOP mulls ending birthright citizenship". The Washington Times. 3 November 2005. http://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2005/nov/03/20051103-115741-1048r/. Retrieved 6 September 2009.

- ^ See Raoul Berger, Government by Judiciary, The Transformation of the Fourteenth Amendment, 64-66 (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund 1997) (1977).

- ^ Basic Law of Hong Kong

- ^ Chen, Albert H. Y. (2011). "The Rule of Law under 'One Country, Two Systems': The Case of Hong Kong 1997–2010". National Taiwan University Law Review 6 (1): 269–299. http://www.law.ntu.edu.tw/ntulawreview/articles/6-1/09-Article-Albert%20H.%20Y.%20Chen_p269-299.pdf. Retrieved 2011-10-04

- ^ "Babies Born in Hong Kong to Mainland Women". Hong Kong Monthly Digest of Statistics. September 2011. http://www.statistics.gov.hk/publication/feature_article/B71109FB2011XXXXB0100.pdf. Retrieved 2011-10-04

- ^ "內地來港產子數目5年急增25倍 香港擬收緊綜援". People's Daily. 2008-03-10. http://hm.people.com.cn/BIG5/85423/6976796.html. Retrieved 2011-10-05

Nationality laws (category) By continent AfricaAsiaArmenia · Azerbaijan · Bangladesh · Bhutan · Burma (Myanmar) · China · Cyprus (Northern Cyprus1) · India · Indonesia · Iran · Iraq · Israel · Japan · Kazakhstan · South Korea · Lebanon · Malaysia · Mongolia · Nepal · Pakistan · Philippines · Russia · Singapore · Taiwan · TurkeyOceaniaEuropeAndorra · Austria · Belarus · Belgium · Bulgaria · Croatia · Czech Republic · Denmark · Estonia · Finland · France · Germany · Greece · Hungary · Iceland · Ireland · Italy · Kazakhstan · Latvia · Lithuania · Luxembourg · Macedonia · Malta · Moldova · Monaco · Montenegro · Norway · Netherlands · Poland · Portugal · Romania · Russia · Serbia · Slovakia · Slovenia · Spain · Sweden · Switzerland · Ukraine · United KingdomNorth AmericaSouth AmericaInternational

organizationsBy type Other Defunct Notes 1 Partially unrecognised and thus unclassified by the United Nations geoscheme. It is listed following the member state the UN categorises it under.Categories:- Human migration

- Latin legal terms

- Nationality law

- Philosophical concepts

- Republicanism

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.