- Medieval medicine

-

For contemporary medicine practiced outside of Western Europe, see Islamic medicine, Unani, Byzantine medicine, Traditional Chinese medicine, and Ayurveda.

Astrology played an important part in Medieval medicine; most educated physicians were trained in at least the basics of astrology to use in their practice.

Astrology played an important part in Medieval medicine; most educated physicians were trained in at least the basics of astrology to use in their practice.

Medieval medicine in Western Europe was composed of a mixture of existing ideas from antiquity, spiritual influences and what Claude Lévi-Strauss identifies as the "shamanistic complex" and "social consensus."[1] In this era, there was no tradition of scientific medicine, and observations went hand-in-hand with spiritual influences.

In the early Middle Ages, following the fall of the Roman Empire, standard medical knowledge was based chiefly upon surviving Greek and Roman texts, preserved in monasteries and elsewhere.[2] Ideas about the origin and cure of disease were not, however, purely secular, but were also based on a world view in which factors such as destiny, sin, and astral influences played as great a part as any physical cause. The efficacy of cures was similarly bound in the beliefs of patient and doctor rather than empirical evidence, so that remedia physicalia (physical remedies) were often subordinate to spiritual intervention.

Contents

Influences

As Christianity grew in influence, a tension developed under the church and folk-medicine, since much in folk medicine was magical, or mystical, and had its basis in sources that were not compatible with Christian faith. Spells and incantations were used in conjunction with herbs and other remedies. Such spells had to be separated from the physical remedies, or replaced with Christian prayers or devotions. Similarly, the dependence upon the power of herbs or gems needed to be explained through Christianity.

The church taught that God sometimes sent illness as a punishment, and that in these cases, repentance could lead to a recovery. This led to the practice of penance and pilgrimage as a means of curing illness. In the Middle Ages, some people did not consider medicine a profession suitable for Christians, as disease was often considered God-sent. God was considered to be the "divine physician" who sent illness or healing depending on his will. However, many monastic orders, particularly the Benedictines, considered the care of the sick as their chief work of mercy.[citation needed]

Medieval European medicine became more developed during the Renaissance of the 12th century, when many medical texts both on ancient Greek medicine and on Islamic medicine were translated from Arabic during the 12th century. The most influential among these texts was Avicenna's The Canon of Medicine, a medical encyclopedia written in circa 1030 which summarized the medicine of Greek, Indian and Muslim physicians up until that time. The Canon became an authoritative text in European medical education up until the early modern period. Other influential translated medical texts at the time included the Hippocratic Corpus attributed to Hippocrates, Alkindus' De Gradibus, the Liber pantegni of Haly Abbas and Isaac Israeli ben Solomon, Abulcasis' Al-Tasrif, and the writings of Galen.

The medieval system

Starting in the areas least affected by the disruption of the fall of the western empire, a unified theory of medicine began to develop, based largely on the writings of the Greek physicians on physiology, hygiene, dietetics, pathology, and pharmacology, and is credited with the discovery of how the spinal cord controls various muscles. From Gentile's dissections, he described the heart valves and determined the purpose of the bladder and kidneys.

Galen of Pergamum, also a Greek, was the most influential ancient physician during this period. In of his undisputed authority over medicine in the Middle Ages, his principal doctrines require some elaboration. Galen described the four classic symptoms of inflammation (redness, pain, heat, and swelling) and added much to the knowledge of infectious disease and pharmacology. His anatomic knowledge of humans was defective because it was based on dissection of pigs. Some of Galen's teachings tended to hold back medical progress. His theory, for example, that the blood carried the pneuma, or life spirit, which gave it its red colour, coupled with the erroneous notion that the blood passed through a porous wall between the ventricles of the heart, delayed the understanding of circulation and did much to discourage research in physiology. His most important work, however, was in the field of the form and function of muscles and the function of the areas of the spinal cord. He also excelled in diagnosis and prognosis. The importance of Galen's work cannot be overestimated, for through his writings knowledge of Greek medicine was subsequently transmitted to the Western world by the Arabs.

Anglo-Saxon translations of classical works like Dioscorides Herbal survive from the 10th Century, showing the persistence of elements of classical medical knowledge. Compendiums like Bald's Leechbook (circa 900), include citations from a variety of classical works alongside local folk remedies.

Although in the Byzantine Empire the organized practice of medicine never ceased (see Byzantine medicine), the revival of methodical medical instruction from standard texts in the west can be traced to the church-run Schola Medica Salernitana in Southern Italy in the Eleventh century. At Salerno medical texts from Byzantium and the Arab world (see Medicine in medieval Islam) were readily available, translated from the Greek and Arabic at the nearby monastic centre of Monte Cassino. The Salernitan masters gradually established a canon of writings, known as the ars medicinae (art of medicine) or articella (little art), which became the basis of European medical education for several centuries.

From the founding of the Universities of Paris (1150), Bologna (1158), Oxford, (1167), Montpelier (1181) and Padua (1222), the initial work of Salerno was extended across Europe, and by the Thirteenth century medical leadership had passed to these newer institutions. To qualify as a Doctor of Medicine took ten years including original Arts training, and so the numbers of such fully qualified physicians remained comparatively small.

During the Crusades European medicine began to be influenced by Islamic medicine. Much ink has been spilled on Usamah ibn Munqidhs supposed distaste of European medicine, but as anyone who reads the entire text of his autobiography will notice, his first-hand experience with European medicine is positive - he describes a European doctor successfully treating infected wounds with vinegar and recommends a treatment for scrofula demonstrated to him by an unnamed "Frank"[1].

By the Thirteenth Century many European towns were demanding that physicians have several years of study or training before they could practice. Surgery had a lower status than pure medicine, beginning as a craft tradition until Roger Frugardi of Parma composed his treatise on Surgery around about 1180. A stream of Italian works of greater scope over the next hundred years, spread later into the rest of Europe. Between 1350 and 1365 Theodoric Borgognoni produced a systematic four volume treatise on surgery, the Cyrurgia, which promoted important innovations as well as early forms of antiseptic practice in the treatment of injury, and surgical anaesthesia using a mixture of opiates and herbs.

The great crisis in European medicine came with the Black Death epidemic in the 14th century. Prevailing medical theories focused on religious rather than scientific explanations.

Theories of medicine

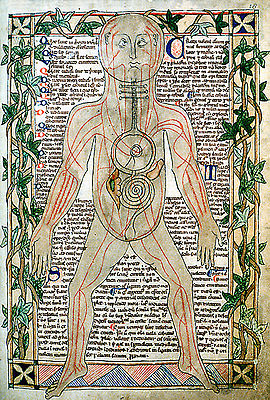

The underlying principle of medieval medicine was the theory of humours. This was derived from the ancient medical works, and dominated all western medicine up until the 19th century. The theory stated that within every individual there were four humours, or principal fluids - black bile, yellow bile, phlegm, and blood, these were produced by various organs in the body, and they had to be in balance for a person to remain healthy. Too much phlegm in the body, for example, caused lung problems; and the body tried to cough up the phlegm to restore a balance. The balance of humours in humans could be achieved by diet, medicines, and by blood-letting, using leeches. The four humours were also associated with the four seasons, black bile-autumn, yellow bile-summer, phlegm-winter and blood-spring.

HUMOUR TEMPER ORGAN NATURE ELEMENT Black bile Melancholic Spleen Cold Dry Earth Phlegm Phlegmatic Lungs Cold Wet Water Blood Sanguine Head Warm Wet Air Yellow bile Choleric Gall Bladder Warm Dry Fire The astrological signs of the zodiac were also thought to be associated with certain humours. Even now, some still use words "choleric", "sanguine", "phlegmatic" and "melancholy" to describe personalities.

The use of herbs dovetailed naturally with this system, the success of herbal remedies being ascribed to their action upon the humours within the body. The use of herbs also drew upon the medieval Christian doctrine of signatures which stated that God had provided some form of alleviation for every ill, and that these things, be they animal, vegetable or mineral, carried a mark or a signature upon them that gave an indication of their usefulness. For example, the seeds of skullcap (used as a headache remedy) can appear to look like miniature skulls; and the white spotted leaves of Lungwort (used for tuberculosis) bear a similarity to the lungs of a diseased patient. A large number of such resemblances are believed to exist.

Most monasteries developed herb gardens for use in the production of herbal cures, and these remained a part of folk medicine, as well as being used by some professional physicians. Books of herbal remedies were produced, one of the most famous being the Welsh, Red Book of Hergest, dating from around 1400.

The hospital system

In the Medieval period the term hospital encompassed hostels for travellers, dispensaries for poor relief, clinics and surgeries for the injured, and homes for the blind, lame, elderly, and mentally ill. Monastic hospitals developed many treatments, both therapeutic and spiritual.

During the thirteenth century an immense number of hospitals were built. The Italian cities were the leaders of the movement. Milan had no fewer than a dozen hospitals and Florence before the end of the Fourteenth century had some thirty hospitals. Some of these were very beautiful buildings. At Milan a portion of the general hospital was designed by Bramante and another part of it by Michelangelo. The Hospital of Sienna, built in honor of St. Catherine, has been famous ever since. Everywhere throughout Europe this hospital movement spread. Virchow, the great German pathologist, in an article on hospitals, showed that every city of Germany of five thousand inhabitants had its hospital. He traced all of this hospital movement to Pope Innocent III, and though he was least papistically inclined, Virchow did not hesitate to give extremely high praise to this pontiff for all that he had accomplished for the benefit of children and suffering mankind.[3]

Hospitals began to appear in great numbers in France and England. Following the French Norman invasion into England, the explosion of French ideals led most Medieval monasteries to develop a hospitium or hospice for pilgrims. This hospitium eventually developed into what we now understand as a hospital, with various monks and lay helpers providing the medical care for sick pilgrims and victims of the numerous plagues and chronic diseases that afflicted Medieval Western Europe. Benjamin Gordon supports the theory that the hospital – as we know it - is a French invention, but that it was originally developed for isolating lepers and plague victims, and only later undergoing modification to serve the pilgrim.[4]

Owing to a well-preserved 12th century account of the monk Eadmer of the Canterbury cathedral, there is an excellent account of Bishop Lanfranc's aim to establish and maintain examples of these early hospitals:

But I must not conclude my work by omitting what he did for the poor outside the walls of the city Canterbury. In brief, he constructed a decent and ample house of stone…for different needs and conveniences. He divided the main building into two, appointing one part for men oppressed by various kinds of infirmities and the other for women in a bad state of health. He also made arrangements for their clothing and daily food, appointing ministers and guardians to take all measures so that nothing should be lacking for them.[5]

Later developments

High medieval surgeons like Mondino de Liuzzi pioneered anatomy in European universities and conducted systematic human dissections. Unlike pagan rome, high medieval Europe did not have a complete ban on human dissection. However, Galenic influence was still so prevalent that Mondino and his contemporaries attempted to fit their human findings into Galenic anatomy.

During the period of the Renaissance from the mid 1450s onward, there were many advances in medical practice. The Italian Girolamo Fracastoro, 1478–1553, was the first to propose that epidemic diseases might be caused by objects outside the body that could be transmitted by direct or indirect contact. He also discovered new treatments for diseases such as syphilis.

In 1543 the Flemish Scholar Andreas Vesalius wrote the first complete textbook on human anatomy: "De Humani Corporis Fabrica", meaning "On the Fabric of the Human Body". Much later, in 1628, William Harvey explained the circulation of blood through the body in veins and arteries. It was previously thought that blood was the product of food and was absorbed by muscle tissue.

During the 16th century, Paracelsus, like Girolamo, discovered that illness was caused by agents outside the body such as bacteria, not by imbalances within the body.

Leonardo Da Vinci also had a large impact on medical advances during the Renaissance. Born on April 15, 1452, Da Vinci's approach to science was based on detailed observation. He participated in several autopsies and created many detailed anatomical drawings, planning a major work of comparative human anatomy.

The French army doctor Ambroise Paré, born in 1510, revived the ancient Greek method of tying off blood vessels. After amputation the common procedure was to cauterize the open end of the amputated appendage to stop the haemorrhaging. This was done by heating oil, water, or metal and touching it to the wound to seal off the blood vessels. Pare also believed in dressing wounds with clean bandages and ointments, including one he made himself composed of eggs, oil of roses, and turpentine. He was the first to design artificial hands and limbs for amputation patients. On one of the artificial hands, the two pairs of fingers could be moved for simple grabbing and releasing tasks and the hand look perfectly natural underneath a glove.

Medical catastrophes were more common in the Renaissance than they are today. During the Renaissance, trade routes were the perfect means of transportation for disease. Eight hundred years after the Plague of Justinian, the bubonic plague returned to Europe. Starting in Asia, the Black Death reached Mediterranean and western Europe in 1348 (possibly from Italian merchants fleeing fighting in Crimea), and killed 25 million Europeans in six years, approximately 1/3 of the total population and up to a 2/3 in the worst-affected urban areas. Before Mongols left besieged Crimean Kaffa the dead or dying bodies of the infected soldiers were loaded onto catapults and launched over Kaffa's walls to infect those inside. This incident was among the earliest known examples of biological warfare and is credited as being the source of the spread of the Black Death into Europe.

The plague repeatedly returned to haunt Europe and the Mediterranean from 14th through 17th centuries. Notable later outbreaks include the Italian Plague of 1629-1631, the Great Plague of Seville (1647–1652), the Great Plague of London (1665–1666), the Great Plague of Vienna (1679), the Great Plague of Marseille in 1720–1722 and the 1771 plague in Moscow.

Before the Spanish came to America and Mexico, the deadly germs of smallpox, measles, and influenza were unheard of. The Native Americans did not have the immunities the Europeans developed through long contact with the diseases. Christopher Columbus ended the Americas' isolation in 1492 while sailing under the flag of Castile, Spain. Deadly epidemics swept across the Caribbean. Smallpox wiped out villages in a matter of months. The island of Hispaniola had a population of 250,000 Native Americans. 20 years later, the population had dramatically dropped to 6,000. 50 years later, it was estimated that approximately 500 Native Americans were left. Smallpox then spread to Mexico where it then helped destroy the Aztec Empire. In the 1st century of Spanish rule in Mexico, 1500–1600, Central and South Americans died by the millions. By 1650, the majority of Mexico's population had perished.

Contrary to popular belief[6] bathing and sanitation were not lost in Europe with the collapse of the Roman Empire.[7][8] Bathing in fact did not fall out of fashion in Europe until shortly after the Renaissance, replaced by the heavy use of sweat-bathing and perfume, as it was thought in Europe that water could carry disease into the body through the skin. Medieval church authorities believed that public bathing created an environment open to immorality and disease. Roman Catholic Church officials even banned public bathing in an unsuccessful effort to halt syphilis epidemics from sweeping Europe.[9]

See also

- Byzantine medicine

- Irish medical families

- Islamic medicine

- Life expectancy

- Medieval demography

- Theriac

- Ibn Sina Academy of Medieval Medicine and Sciences

- Beak doctor costume

- Plague doctor contract

- Plague doctor

Footnotes

- ^ Anthropologie structurale, Lévi-Strauss, Claude (1958, Structural Anthropology, trans. Claire Jacobson and Brooke Grundfest Schoepf, 1963)

- ^ "Medicine in the Middle Ages". http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/medicine_in_the_middle_ages.htm. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- ^ Walsh, James Joseph (1924). The world's debt to the Catholic Church. The Stratford Company. pp. 244.

- ^ Gordon, Benjamin (1959). Medieval and Renaissance Medicine. New York: Philosophical Library. pp. 341.

- ^ Orme, Nicholas (1995). The English Hospital: 1070-1570. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press. pp. 21–22.

- ^ The Bad Old Days — Weddings & Hygiene

- ^ The Great Famine (1315-1317) and the Black Death (1346-1351)

- ^ Middle Ages Hygiene

- ^ Paige, John C; Laura Woulliere Harrison (1987). Out of the Vapors: A Social and Architectural History of Bathhouse Row, Hot Springs National Park. U.S. Department of the Interior. http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/hosp/bathhouse_row.pdf.

References

- The Greatest Benefit to Mankind. A medical history of humanity from antiquity to the present. Roy Porter. HaperCollins 1997

- Medicine in the English Middle Ages. Faye Getz, Princeton University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-691-08522-6

External links

- Medieval Medicine

- "Index of Medieval Medical Images" UCLA Special Collections (accessed 2 September 2006).

- "The Wise Woman" An overview of common ailments and their treatments from the Middle Ages presented in a slightly humorous light.

- "MacKinney Collection of Medieval Medical Illustrations"

- PODCAST: Professor Peregrine Horden (Royal Holloway University of London): 'What's wrong with medieval medicine?'

- Walsh, James J. Medieval Medicine(1920), A & C Black, Ltd.

European Middle Ages Architecture · Art · Cuisine · Demography · Literature · Poetry · Medicine · Music · Philosophy · Science · Technology · Warfare · Household · SlaveryCategories:- History of medieval medicine

- Middle Ages

- Humorism

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.