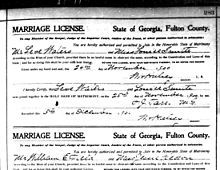

- Marriage licence

-

A marriage license is a document issued, either by a church or state authority, authorizing a couple to marry. The procedure for obtaining a license varies between countries and has changed over time. Marriage licenses began to be issued in the Middle Ages, to permit a marriage which would otherwise be illegal (for instance, if the necessary period of notice for the marriage had not been given).

Today, they are a legal requirement in some jurisdictions and may also serve as the record of the marriage itself, if signed by the couple and witnessed.

In other jurisdictions, a license is not required. In some jurisdictions, a "pardon" can be obtained, for marrying without a license and in some jurisdictions, common-law marriages and marriage by cohabitation and representation are also recognised. These do not require a marriage license. There are also some jurisdictions where marriage licenses do not exist at all and a marriage certificate is given to the couple after the marriage ceremony did take place.

Article 16 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights declares that "Men and women of full age, without any limitation due to race, nationality or religion, have the right to marry and to found a family. They are entitled to equal rights as to marriage, during marriage and at its dissolution. Marriage shall be entered into only with the free and full consent of the intending spouses."

Contents

History

For most of Western history, marriage was a private contract between two families. Until the 16th-century, Christian churches accepted the validity of a marriage on the basis of a couple’s declarations. If two people claimed that they had exchanged marital vows—even without witnesses—the Catholic Church accepted that they were validly married.

State courts in the United States* have routinely held that public cohabitation was sufficient evidence of a valid marriage.[1] Marriage license application records from government authorities are widely available starting from the mid-19th century with many available dating from the 17th century in colonial America.[2] Marriage licenses from their inception have sought to establish certain prohibitions on the institution of marriage. These prohibitions have changed throughout history. In the 1920s, they were used by 38 states to prohibit whites from marrying blacks, mulattos, Japanese, Chinese, Indians, Mongolians, Malays or Filipinos without a state approved license.[1] At least 32 nations have established significant prohibitions on same-sex marriage.[3]

United Kingdom

England & Wales

A requirement for banns of marriage was introduced to England and Wales by the Church in 1215. This required a public announcement of a forthcoming marriage, in the couple's parish church, for three Sundays prior to the wedding and gave an opportunity for any objections to the marriage to be voiced (for example, that one of the parties was already married), but a failure to call banns did not affect the validity of the marriage.

Marriage licenses were introduced in the 14th century, to allow the usual notice period under banns to be waived, on payment of a fee and accompanied by a sworn declaration, that there was no canonical impediment to the marriage. Licenses were usually granted by an archbishop, bishop or archdeacon. There could be a number of reasons for a couple to obtain a license: they might wish to marry quickly (and avoid the three weeks' delay by the calling of banns); they might wish to marry in a parish away from their home parish; or, because a license required payment, they might choose to obtain one as a status symbol.

There were two kinds of marriage licenses that could be issued: the usual was known as a common license and named one or two parishes where the wedding could take place, within the jurisdiction of the person who issued the license. The other was the special license, which could only be granted by the Archbishop of Canterbury or his officials and allowed the marriage to take place in any church.

To obtain a marriage license, the couple or more usually the bridegroom, had to swear that there was no just cause or impediment why they should not marry. This was the marriage allegation. A bond was also lodged with the church authorities for a sum of money to be paid if it turned out that the marriage was contrary to Canon Law. The bishop kept the allegation and bond and issued the license to the groom, who then gave it to the vicar of the church, where they were to get married. There was no obligation, for the vicar to keep the license and many were simply destroyed. Hence, few historical examples of marriage licenses, in England and Wales, survive. However, the allegations and bonds were usually retained and are an important source for English genealogy.

Hardwicke's Marriage Act 1753 affirmed this existing ecclesiastical law and built it into statutory law. From this date, a marriage was only legally valid, if it followed the calling of banns in church or the obtaining of a license—the only exceptions being Jewish and Quaker marriages, whose legality was also recognised. From the date of Lord Hardwicke's Marriage Act, up to 1837, the ceremony was required to be performed in a consecrated building.

Since July 1, 1837, civil marriages have been a legal alternative to church marriages, under the Marriage Act 1836, which provided the statutory basis for regulating and recording marriages. So, today, a couple has a choice between being married in the Anglican Church, after the calling of banns or obtaining a license or else, they can give "Notice of Marriage" to a civil registrar. In this latter case, the notice is publicly posted for 15 days, after which a civil marriage can take place. Marriages may take place in churches other than Anglican churches, but these are governed by civil marriage law and notice must be given to the civil registrar in the same way. The marriage may then take place without a registrar being present, if the church itself is registered for marriages and the minister or priest is an Authorised Person for marriages.

The license does not record the marriage itself, only the permission for a marriage to take place. Since 1837, the proof of a marriage has been by a marriage certificate, issued at the ceremony; before then, it was by the recording of the marriage in a parish register.

The provisions on civil marriage in the 1836 Act were repealed by the Marriage Act 1949. The Marriage Act 1949 re-enacted and re-stated the law on marriage in England and Wales.

Scotland

Marriage law and practice in Scotland differs from that in England and Wales. Historically, it was always considered legal and binding for a couple to marry by making public promises, without a formal ceremony. Church marriages "without proclamation" are somewhat analogous to the English "marriages by license", although licenses were not formally issued in Scotland. However, in modern times, the English and Scottish systems have been brought into line: all legal marriages in Scotland take place according to a similar system to that for English civil marriages.

United States

The specifications for obtaining a marriage license vary between states. In general, however, both parties must appear in person at the time the license is obtained; be of marriageable age (i.e. over 18 years; lower in some states with the consent of a parent); present proper identification (typically a driver's license, state ID card, birth certificate or passport; more documentation may be required for those born outside of the United States); and neither must be married to anyone else (proof of spouse's death or divorce may be required, by someone who had been previously married in some states).

Many states require 1 to 6 days to pass, between the granting of the license and the marriage ceremony. After the marriage ceremony, both spouses and the officiant sign the marriage license (some states also require a witness). The officiant or couple then files for a certified copy of the marriage license and a marriage certificate with the appropriate authority. Some states also have a requirement that a license be filed within a certain time after its issuance, typically 30 or 60 days, following which a new license must be obtained.

The requirement for marriage licenses in the U.S. has been justified on the basis that the state has an overriding right, on behalf of all citizens and in the interests of the larger social welfare, to protect them from disease or improper/illegal marriages; to keep accurate state records; or even to ensure that marriage partners have had adequate time to think carefully before marrying.[citation needed]

Some states require a blood test to verify that the applicants are not carrying syphilis, a sexually-transmitted disease. As of 2010, Mississippi and Montana require blood tests; Connecticut, Wisconsin, Georgia, Indiana, Oklahoma, Massachusetts, and the District of Columbia have withdrawn the blood testing requirements in the last few years.[citation needed]

In the early part of the 20th century, the requirement for a marriage license was used as a mechanism to prohibit whites from marrying blacks, mulattos, Japanese, Chinese, Native Americans, Mongolians, Malays or Filipinos.[1] By the 1920s, 38 states used the mechanism. These laws have since been declared invalid by the Courts.

In the United States, until the mid-19th century, common-law marriages were recognised as valid, but thereafter the states began to invalidate common-law marriages. At present eleven states and the District of Columbia recognise common-law marriages. (See Common-law marriage in the United States.) Common-law marriages, if recognised, are valid, notwithstanding the absence of a marriage license.

However, with the resurgence of the historical Supreme Court case Meister v. Moore in 1877, the Supreme Court has ruled that "marriage is a common right" and that the state laws or statutes that have been created before or since are not legal constraints, but "are mere directives," thereby retaining the legal weight of recommendation only. Because of this Federal license, it is illegal for any state to mandate any form of license or ceremony and, technically, all states must recognize "common law" marriages of all citizens.[4]

Marriage licenses in the United States fall under provincial jurisdiction but are recognized across the country. Additional work is required to obtain the licenses when citizens from multiple states are being married. In any case, the state in which they are married holds the record of that marriage. Traditionally, law working with law enforcement was the only means of searching and accessing marriage licence information across state lines.[5]

Controversy in the US

Some groups believe that the requirement to obtain a marriage license is unnecessary or immoral. The Libertarian Party, for instance, believes that all marriages should be civil, not requiring sanction from the state.[6][7] Some Christian groups also argue that a marriage is a contract between two people and God, so no authorization from the state is required. In some US states, the state is cited as a party in the marriage contract [8] which is seen by some as an infringement.[9]

Marriage licenses have also been the subject of controversy for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community whose ability to marry is often limited by state regulations. Perhaps most notably, California's Proposition 8 has been the subject of heavy criticism by advocates of same-sex marriage.[10]

In October 2009, Keith Bardwell, a Louisiana justice of the peace, refused to issue a marriage license to an interracial couple, prompting civil liberties groups, such as the NAACP and ACLU, to call for his resignation or firing.[11][12] Bardwell resigned his office on November 3.[13]

The marriage laws and license requirements of many states originated from the ideas of eugenics.[14]

The Netherlands and Belgium

In the Netherlands and Belgium, couples intending to marry are required to register their intention beforehand, a process called "ondertrouw".

See also

People

- Robert Stewart Sparks, in charge of Los Angeles, California, marriage-licence division, 20th century

Notes

- ^ a b c Coontz, Stephanie (November 26, 2007). "Taking Marriage Private". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/26/opinion/26coontz.html?pagewanted=all. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ^ Szucs, Loretto Dennis, and Sandra Hargreaves Luebking. The Source: A Guidebook to American Genealogy. Provo, UT: Ancestry, 2006. Pages 87 to 103.

- ^ Nolan, LC., Wardle, LD, Fundamental principles of family law, p. 118-119 Wm. S. Hein Publishing, 2005 ISBN 0837738326, 9780837738321 http://books.google.com/books?id=WjgL3ha8OSQC

- ^ "Meister v. Moore, 96 U.S. 76". http://supreme.justia.com/us/96/76/case.html. Retrieved 2011-08-26.

- ^ "Marriage Records Records Retrieval". http://www.marriage-licences.com/. Retrieved 2011-09-05.

- ^ Statement of Principles; 1.3 Personal Relationships

- ^ Michael Badnarik. Michael Badnarik's Constitution Class. Event occurs at 00:06:43. http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=-4944712480955285875#docid=1338165539518441611. Retrieved 2010-07-26. "If you go to a wedding, how many people are in that contract? Well you've got the man, you've got the woman, but that's not all you've also got the state! The state is there, giving you permission. Why? Because you asked."

- ^ Information from Ohio Legal Services

- ^ Arguments against marriage licenses, from Mercy Seat church, Wisconsin

- ^ Same-sex marriage activists seek repeal of California’s Prop. 8

- ^ Justice stands by refusal to give interracial couple license to wed

- ^ Heat Builds in Interracial Marriage Denial

- ^ "Justice of peace in marriage flap resigns". United Press International. November 3, 2009. http://www.upi.com/Top_News/US/2009/11/03/Justice-of-peace-in-marriage-flap-resigns/UPI-71711257294201/. Retrieved November 4, 2009.

- ^ Journal of heredity; eugenic origins of marriage laws

References

- Mark D. Herber, Ancestral Trails - The complete guide to British genealogy and family history, Sutton Publishing, 1997, ISBN 0-7509-1418-1

- C R Chapman & P M Litton, Marriage laws, rites, records and customs, Lochin Publishing, 1996

- National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws, American Uniform Marriage and Marriage License Act, Railway Printing Company, 1911

External links

- Marriage Laws Chart of the USA

- Complete guide to getting copies of marriage licenses by US State - www.vitalrecordsguide.com: marriage license

- Las Vegas Marriage License Information

- Marriage Certificate of Abraham Lincoln and Mary Todd (link is broken)

- Information on blood tests, waiting periods, and length of time for which the license is valid in the United States.

Categories:- Licenses

- Marriage

- Pre-wedding

- Vital statistics

- Personal documents

- Genealogy

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.