- United States presidential election, 1844

-

United States presidential election, 1844

1840 ← November 1 - December 4, 1844 → 1848

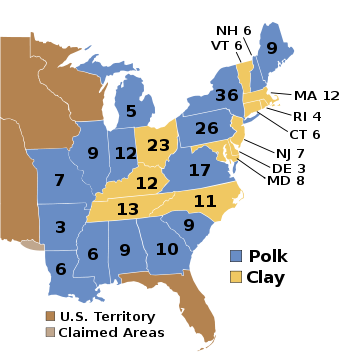

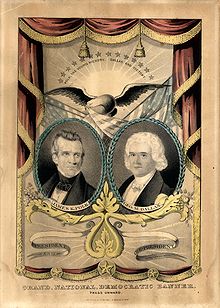

Nominee James K. Polk Henry Clay Party Democratic Whig Home state Tennessee Kentucky Running mate George M. Dallas Theodore Frelinghuysen Electoral vote 170 105 States carried 15 11 Popular vote 1,339,494 1,300,004 Percentage 49.5% 48.1%

Presidential election results map. Blue denotes states won by Polk/Dallas, Orange denotes those won by Clay/Frelinghuysen. Numbers indicate the number of electoral votes allotted to each state.

President before election

Elected President

In the United States presidential election of 1844, Democrat James K. Polk defeated Whig Henry Clay in a close contest that turned on foreign policy, with Polk favoring the annexation of Texas and Clay opposed.

Democratic nominee James K. Polk ran on a platform that embraced American territorial expansionism, an idea soon to be referred to as Manifest Destiny. At their convention, the Democrats called for the annexation of Texas and asserted that the United States had a “clear and unquestionable” claim to “the whole” of Oregon. By informally tying the Oregon boundary dispute to the more controversial Texas debate, the Democrats appealed to both Northern expansionists (who were more adamant about the Oregon boundary) and Southern expansionists (who were more focused on annexing Texas as a slave state). Polk went on to win a narrow victory over Whig candidate Henry Clay, in part because Clay had taken a stand against expansion, although economic issues were also of great importance. (The slogan "Fifty-four Forty or Fight!” is often incorrectly regarded as being part this president's election campaign rhetoric; it became a popular slogan in the months after the election, used by those proposing the most extreme solution to the Oregon boundary dispute).

This was the last presidential election to be held on different days in different states. Starting with the presidential election of 1848, all states held the election on the same date in November.

Contents

Background

The incumbent President in 1844 was John Tyler, who had ascended to the office of President upon the death of William Henry Harrison. Although Tyler had been nominated on a Whig ticket, his policies had alienated the Whigs and they actually expelled him from the party on September 13, 1841. Without a home in either of the two major parties, Tyler sought an issue that could create a viable third party to support his bid for the presidency in 1844.

Tyler found that issue in the annexation of Texas. When Texas achieved independence in 1836, it initially sought to be annexed by the United States. Opposition from the northern states prevented the United States from acting favorably on this request, and in 1838 Texas withdrew its request. There the issue lay until 1843, when Tyler and his newly-appointed Secretary of State, Abel P. Upshur, raised the matter again and started negotiations on annexation. When Upshur was killed in an accident on February 28, 1844, the treaty was almost complete. Tyler appointed John C. Calhoun Secretary of State as Upshur's replacement, and Calhoun completed the treaty; it was presented to the Senate on April 22. However, Calhoun had also sent a letter to British Minister Richard Pakenham that charged the British with attempting to coerce Texas into abolishing slavery. This claim was used to justify the annexation as a defensive move to preserve southern slavery. Calhoun presented the letter to Senate along with the treaty. Going into the presidential campaign season, Texas annexation was thus explicitly tied to southern slavery and suddenly emerged as the top issue.

Nominations

Whig Party nomination

Whig candidates

- Henry Clay, U.S. senator from Kentucky

Candidates gallery

The Whigs held their convention on May 1. Clay, the party's most prominent congressional leader, was chosen on the first ballot despite having lost two prior presidential elections: in 1824 to John Quincy Adams as a Democrat-Republican, then in 1832 to Andrew Jackson as a National Republican. Theodore Frelinghuysen was nominated as Clay's running mate.

Convention vote Presidential vote 1 Vice Presidential vote 1 2 3 Henry Clay 275 Theodore Frelinghuysen 101 118 154 John Davis 83 75 79 Millard Fillmore 53 51 40 John Sergeant 38 33 0 Abstaining 0 0 2 Democratic Party nomination

Main article: 1844 Democratic National ConventionDemocratic candidates

- James K. Polk, former Governor from Tennessee

- Martin Van Buren, former President from New York

- Lewis Cass, U.S. senator from Michigan

- Richard M. Johnson, former Vice President from Kentucky

- James Buchanan, U.S. senator from Pennsylvania

- John C. Calhoun, former Vice President from South Carolina

- Levi Woodbury, U.S. senator from New Hampshire

Candidates gallery

-

Secretary of State John C. Calhoun of South Carolina

-

United States Senator Levi Woodbury of New Hampshire

The Democrats met in Baltimore on May 27.

While Van Buren held a slim majority of delegates, his public stand against immediate annexation had increased the hostility of the opposition. Early in the convention, the delegates drew up rules for approving the platform and the candidate. At the instigation of Robert J. Walker of Mississippi, the convention re-established the rule that a Democratic candidate must receive a 2/3 majority of delegates to receive the nomination. (Ironically, the rule had first been used in 1832 to secure the nomination of Van Buren to the Vice Presidency over John C. Calhoun.) This fatally wounded Van Buren's candidacy; as it became clear that too many delegates were hostile to Van Buren for him ever to receive the necessary majority, his support collapsed.

Finally, on the eighth ballot, a new name was introduced: James K. Polk, who had intended to seek the vice presidential nomination. While he did not receive the necessary votes to win on this ballot, the momentum was clearly in his direction, and he won the necessary 2/3 on the following ballot, making Polk the first “dark horse” candidate.

The Democrats chose Silas Wright as Polk's running mate, but Wright refused the nomination. George Mifflin Dallas, who had finished a close second to Wright in the balloting, was then offered a spot on the ticket, and he accepted.

When advised of his nomination via letter, Polk replied: “It has been well observed that the office of President of the United States should neither be sought nor declined. I have never sought it, nor should I feel at liberty to decline it, if conferred upon me by the voluntary suffrages of my fellow citizens.”

Convention Presidential vote Ballots 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

Before shifts9

After shiftsMartin Van Buren 146 127 121 111 103 101 99 104 0 0 Lewis Cass 83 94 92 105 107 116 123 114 29 0 Richard M. Johnson 24 33 38 32 29 23 21 0 0 0 John C. Calhoun 6 1 2 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 James Buchanan 4 9 11 17 26 25 22 0 0 0 Levi Woodbury 2 1 2 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Charles Stewart 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 James K. Polk 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 44 231 266 Abstaining 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 4 6 0 Convention Vice Presidential vote Ballots 1 2 3 Silas Wright 258 0 0 John Fairfield 0 107 30 Levi Woodbury 8 44 6 Lewis Cass 0 39 0 Richard M. Johnson 0 26 0 Charles Stewart 0 23 0 George M. Dallas 0 13 230 William L. Marcy 0 5 0 Abstaining 0 11 0 National Democratic Tyler Convention

The National Democratic Tyler Convention assembled in Baltimore on May 27 and May 28, the same time as the Democratic National Convention. It nominated Tyler for a second term, but did not recommend a choice for Vice President. It is possible that the convention hoped to influence the Democratic National Convention.[1] Tyler was at first enthusiastic about his chances and accepted their nomination; his address was referenced in the New Hampshire Patriot and State Gazette on June 6, but the paper did not print the text of Tyler's letter.

Other nominations

Joseph Smith, Jr., mayor of Nauvoo, Illinois and founder of the Latter Day Saint movement, ran as an independent. He proposed the redemption of slaves by selling public lands and decreasing the size and salary of the United States Congress; the closure of prisons; the annexation of Texas, Oregon, and parts of Canada; the securing of international rights on high seas; free trade; and the re-establishment of a national bank.[2] The campaign ended when he was assassinated while in prison on June 27, 1844.

James Birney[disambiguation needed

] ran as the anti-slavery Liberty Party candidate, garnering 2.3% of the popular vote, and over 8% of the vote in Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Vermont. The votes he won were more than the difference in votes between Henry Clay and James K. Polk; some scholars have argued that Birney's support among anti-slavery Whigs in New York swung that decisive state in favor of Polk (see below).

] ran as the anti-slavery Liberty Party candidate, garnering 2.3% of the popular vote, and over 8% of the vote in Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Vermont. The votes he won were more than the difference in votes between Henry Clay and James K. Polk; some scholars have argued that Birney's support among anti-slavery Whigs in New York swung that decisive state in favor of Polk (see below).General election

Campaign

Tyler drops out

Tyler spent much of the summer with his new bride on their honeymoon in New York City. While there, he discovered that his support was quite soft. He also received appeals from Democrats to withdraw, including a letter from Andrew Jackson.[3] Tyler wrote a letter in which he withdrew from the race around August 25; it was announced in several newspapers on August 29, including the New Hampshire Patriot and State Gazette, the Berkshire County Whig, and the Barre Gazette. The New Hampshire Patriot and State Gazette stated that Tyler withdrew for fear that his candidacy would divide the votes going to Polk, and potentially lead to the election of Clay.

Clay and Polk

The Whigs initially played on Polk's comparative obscurity, asking “just who is James K. Polk?” as part of their campaign to get Clay elected.

Polk was committed to territorial expansion and favored the annexation of Texas. To deflect charges of pro-slavery bias in the Texas annexation issue, Polk combined the Texas annexation issue with a demand for the acquisition of the entire Oregon Territory, which was at the time jointly administered by the United States and the United Kingdom. This proved to be an immensely popular message, especially compared to the Whigs' economic program. It even forced Clay to move on the issue of Texas annexation, saying that he would support annexation after all if it could be accomplished without war and upon “just and fair” terms.

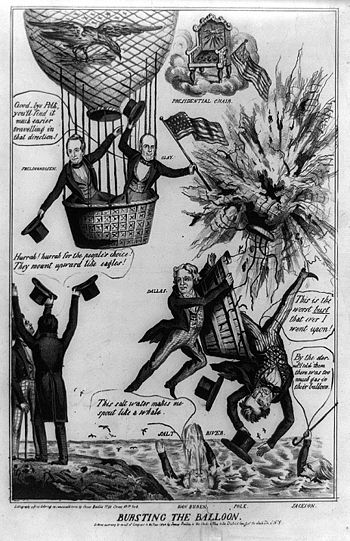

Results

The election was very close run. The anti-slavery Liberty Party may well have played the role of spoiler:[4] in New York state, Birney received 15,800 votes—significantly more than Polk's slim margin of victory (5,100 votes). A victory in New York would have given Clay a decisive 141-134 edge in the electoral college. Some historians have therefore speculated that Clay's ambiguous stance on Texas cost him critical anti-slavery votes in New York, and tipped the overall election to the Democrats. On the other hand, Clay won an extremely narrow victory in largely pro-Texas Tennessee (123 votes); if he had adopted a more forthright anti-Texas position, he may well have lost that state's 13 electoral votes, enough to give the election back to Polk in any case.

Presidential candidate Party Home state Popular vote(a) Electoral

voteRunning mate Count Pct Vice-presidential candidate Home state Elect. vote James K. Polk Democratic Tennessee 1,339,494 49.5% 170 George M. Dallas Pennsylvania 170 Henry Clay Whig Kentucky 1,300,004 48.1% 105 Theodore Frelinghuysen New York[5] 105 James G. Birney Liberty New York 62,103 2.3% 0 Thomas Morris Ohio 0 Other 2,058 0.1% — Other — Total 2,703,659 100% 275 275 Needed to win 138 138 Source (Popular Vote): Leip, David. 1844 Presidential Election Results. Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections (July 27, 2005). Source (Electoral Vote): Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996. Official website of the National Archives. (July 31, 2005).

(a) The popular vote figures exclude South Carolina where the Electors were chosen by the state legislature rather than by popular vote.

Electoral college selection

Method of choosing Electors State(s) Each Elector appointed by state legislature South Carolina Each Elector chosen by voters statewide (all other States) Consequences

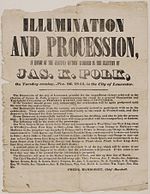

Broadside announcing torchlight victory parade in Lancaster, Pennsylvania

Broadside announcing torchlight victory parade in Lancaster, Pennsylvania

Polk's election confirmed the American public's desire for westward expansion. The annexation of Texas was formalized on March 1, 1845 before Polk even took office. As feared, Mexico refused to accept the annexation and the Mexican-American War broke out in 1846. With Polk's main issue of Texas settled, instead of demanding all of Oregon, he compromised and the United States and United Kingdom negotiated the Buchanan-Pakenham Treaty, which divided up the Oregon Territory between the two countries.

See also

- History of the United States (1789-1849)

- Second Party System

- United States House elections, 1844

Notes

- ^ Hinshaw, Seth B. (2000). Ohio Elects the President. Mansfield, Ohio: Book Masters. pp. 27.

- ^ Smith, Joseph, Jr. (1844), General Smith's Views on the Powers and Policy of the Government of the United States, http://contentdm.lib.byu.edu/u?/NCMP1820-1846,2597.

- ^ Wilentz, 573.

- ^ "Third Party Tickets: Bubbles That Have Floated for a While on the Political Sea". The New York Times: p. 4. July 24, 1892.

- ^ Frelinghuysen's home state was apparently New York in 1844. See The Journal of the Senate for February 12, 1845. Also note that Frelinghuysen was President of New York University in 1844. There is some contradictory evidence in favor of a New Jersey residency: the National Archives gives his home state as New Jersey and the Journal of the Senate notes that Vermont's electors believed Frelinghuysen to be a New Jersey resident. Frelinghuysen was a New Jersey native and his political career had largely been conducted in New Jersey.

References

- Books

- Blum, John M.; et al. (1963). The National Experience: A History of the United States. Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc. ISBN 0-15-500366-6.

- Chitwood, Oliver Perry (1939). John Tyler, Champion of the Old South.

- Harris, J. George (1990). Wayne Cutler (ed.). ed. Polk's Campaign Biography. University of Tennessee Press.

- Holt, Michael F. (1999). The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party: Jacksonian Politics and the Onset of the Civil War. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505544-6.

- McCormac, Eugene I. (1922). James K. Polk: A Political Biography.

- Paul, James C. N. (1951). Rift in the Democracy.

- Remini, Robert V. (1991). Henry Clay: Statesman for the Union.

- Sellers, Charles Grier, Jr. (1966). James K. Polk, Continentalist, 1843–1846. vol 2 of biography.

- Wilentz, Sean (2005). "Divided Democrats and the Election of 1844". The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln (1st ed. ed.). New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.. pp. 566–575. ISBN 0-393-32921-6.

- Web sites

- "A Historical Analysis of the Electoral College". The Green Papers. http://www.thegreenpapers.com/Hx/ElectoralCollege.html. Retrieved September 17, 2005.

- "Ohio History Central". Ohio History Central Online Encyclopedia. http://www.ohiohistorycentral.org/entry.php?rec=37. Retrieved 2006-11-08.

External links

- 1844 popular vote by counties

- Library of Congress

- Overview of Democratic National Convention 1844

- How close was the 1844 election? — Michael Sheppard, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

United States presidential elections

United States presidential elections1788 · 1792 · 1796 · 1800 · 1804 · 1808 · 1812 · 1816 · 1820 · 1824 · 1828 · 1832 · 1836 · 1840 · 1844 · 1848 · 1852 · 1856 · 1860 · 1864 · 1868 · 1872 · 1876 · 1880 · 1884 · 1888 · 1892 · 1896 · 1900 · 1904 · 1908 · 1912 · 1916 · 1920 · 1924 · 1928 · 1932 · 1936 · 1940 · 1944 · 1948 · 1952 · 1956 · 1960 · 1964 · 1968 · 1972 · 1976 · 1980 · 1984 · 1988 · 1992 · 1996 · 2000 · 2004 · 2008 · 2012

Electoral College · Electoral vote changes · Electoral votes by state · Results by Electoral College margin · Results by popular vote margin · Results by state · Voter turnout · Presidential primaries · Presidential nominating conventionsSee also: House elections · Senate elections · Gubernatorial elections

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.