- HD 209458 b

-

HD 209458 b Extrasolar planet List of extrasolar planets

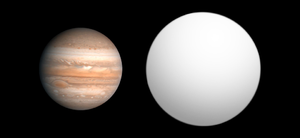

Size comparison of HD 209458 b with Jupiter. Parent star Star HD 209458 Constellation Pegasus Right ascension (α) 22h 03m 10.8s Declination (δ) +18° 53′ 04″ Apparent magnitude (mV) 7.65 Distance 154 ly

(47.1 pc)Spectral type G0V Mass (m) 1.13+0.03

−0.02 M☉Radius (r) 1.14+0.06

−0.05 R☉Temperature (T) 6000 ± 50 K Metallicity [Fe/H] 0.00 ± 0.02 Age 4 ± 2 Gyr Orbital elements Semimajor axis (a) 0.045 AU

(6.7 Gm)Periastron (q) 0.044 AU

(6.6 Gm)Apastron (Q) 0.046 AU

(6.8 Gm)Eccentricity (e) 0.014[1] Orbital period (P) 3.52474541 ± 0.00000025 d (84.5938898 h) Inclination (i) 86.1 ± 0.1° Argument of

periastron(ω) 83° Time of periastron (T0) 2,452,854.825415

± 0.00000025 JDSemi-amplitude (K) 84.26 ± 0.81 m/s Physical characteristics Mass (m) 0.69 ± 0.05 MJ Radius (r) 1.35 ± 0.05 RJ Density (ρ) 370 kg m-3 Surface gravity (g) 18.46 m/s² (1.88 g) Temperature (T) 1,130 ± 150 K Discovery information Discovery date November 5, 1999 Discoverer(s) D. Charbonneau

T. Brown

D. Latham

M. Mayor

G.W. Henry

G. Marcy

R.P. Butler

S.S. VogtDetection method Transit and Radial velocity Discovery site Lowell Observatory

Geneva ObservatoryDiscovery status Published Other designations OsirisDatabase references Extrasolar Planets

Encyclopaediadata SIMBAD data HD 209458 b is an extrasolar planet (unofficially referred to as Osiris) that orbits the Solar analog star HD 209458 in the constellation Pegasus, some 150 light-years from Earth's solar system, with evidence of water vapor.[2] The radius of the planet's orbit is 7 million kilometres, about 0.047 astronomical units, or one eighth the radius of Mercury's orbit. This small radius results in a year that is 3.5 Earth days long and an estimated surface temperature of about 1,000 °C (about 1,800 °F). Its mass is 220 times that of Earth (0.69 Jupiter masses) and its volume is some 2.5 times greater than that of Jupiter. The high mass and great volume of HD 209458 b indicate that it is a gas giant.

HD 209458 b represents a number of milestones in extraplanetary research. It was the first of many categories: a transiting extrasolar planet discovered, an extrasolar planet known to have an atmosphere, an extrasolar planet observed to have an evaporating hydrogen atmosphere, an extrasolar planet found to have an atmosphere containing oxygen and carbon, one of the first two extrasolar planets to be directly observed spectroscopically and the first extrasolar gas giants to have its superstorm measured, and the first planet to have its orbital speed measured, determining its mass directly.[3] Based on the application of new, theoretical models, as of April 2007, it is alleged to be the first extrasolar planet found to have water vapor in its atmosphere.[4][5][6]

HD 209458 is an 8th magnitude star, visible from Earth with binoculars.

Contents

Detection and discovery

Transits

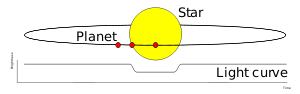

Spectroscopic studies first revealed the presence of a planet around HD 209458 on November 5, 1999. Astronomers had made careful photometric measurements of several stars known to be orbited by planets, in the hope that they might observe a dip in brightness caused by the transit of the planet across the star's face. This would require the planet's orbit to be inclined such that it would pass between the Earth and the star, and previously no transits had been detected.

Soon after the discovery, separate teams, one led by David Charbonneau including Timothy Brown and others, and the other by Gregory W. Henry, were able to detect a transit of the planet across the surface of the star making it the first known transiting extrasolar planet. On September 9 and 16, 1999, Charbonneau's team measured a 1.7% drop in HD 209458's brightness, which was attributed to the passage of the planet across the star. On November 8, Henry's team observed a partial transit, seeing only the ingress.[7] Initially unsure of their results, the Henry group decided to rush their results to publication after overhearing rumors that Charbonneau had successfully seen an entire transit in September. Papers from both teams were published simultaneously in the same issue of the Astrophysical Journal. Each transit lasts about three hours, during which the planet covers about 1.5% of the star's face.

The star had been observed many times by the Hipparcos satellite, which allowed astronomers to calculate the orbital period of HD 209458 b very accurately at 3.524736 days.[8]

Spectroscopic

Spectroscopic analysis had shown that the planet had a mass about 0.69 times that of Jupiter.[9] The occurrence of transits allowed astronomers to calculate the planet's radius, which had not been possible for any previously known exoplanet, and it turned out to have a radius some 35% larger than Jupiter's.

Direct detection

On March 22, 2005, NASA released news that infrared light from the planet had been measured by the Spitzer Space Telescope, the first ever direct detection of light from an extrasolar planet. This was done by subtracting the parent star's constant light and noting the difference as the planet transited in front of the star and was eclipsed behind it, providing a measure of the light from the planet itself. New measurements from this observation determined the planet's temperature as at least 750 °C (1300 °F). The circular orbit of HD 209458 b was also confirmed.

Spectral observation

On February 21, 2007, NASA and Nature released news that HD 209458 b was one of the first two extrasolar planets to have their spectra directly observed, the other one being HD 189733 b.[10][11] This was long seen as the first mechanism by which extrasolar but non-sentient life forms could be searched for, by way of influence on a planet's atmosphere. A group of investigators led by Jeremy Richardson of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center spectrally measured HD 209458 b's atmosphere in the range of 7.5 to 13.2 micrometres. The results defied theoretical expectations in several ways. The spectrum had been predicted to have a peak at 10 micrometres which would have indicated water vapor in the atmosphere, but such a peak was absent, indicating no detectable water vapor. Another unpredicted peak was observed at 9.65 micrometres, which the investigators attributed to clouds of silicate dust, a phenomenon not previously observed. Another unpredicted peak occurred at 7.78 micrometres, which the investigators did not have an explanation for. A separate team led by Mark Swain of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory reanalyzed the Richardson et al. data, and had not yet published their results when the Richardson et al. article came out, but made similar findings.

On 23 June 2010, astronomers announced they have measured a superstorm (with windspeeds of up to 7000 km/h) for the first time in the atmosphere of HD 209458 b.[12] The very high-precision observations done by ESO’s Very Large Telescope and its powerful CRIRES spectrograph of carbon monoxide gas show that it is streaming at enormous speed from the extremely hot day side to the cooler night side of the planet. The observations also allow another exciting “first”—measuring the orbital speed of the exoplanet itself, providing a direct determination of its mass.[3]

Rotation

As of August 2008, the most recent calculation of HD 209458 b's Rossiter-McLaughlin effect and so spin-orbit angle was that of Winn in 2005.[13] This is -4.4 +/- 1.4 degrees.[14]

Physical characteristics

It had been previously hypothesized that hot Jupiters particularly close to their parent star should exhibit this kind of inflation due to intense heating of their outer atmosphere. Tidal heating due to its orbit's eccentricity, which may have been more eccentric at formation, may also have played a role over the past billion years.[15]

Stratosphere and upper clouds

Artist's conception of the extrasolar planet HD 209458 b.

Artist's conception of the extrasolar planet HD 209458 b.

The atmosphere is at a pressure of one bar at an altitude of 1.29 Jupiter radii above the planet's center.[16]

Where the pressure is 33+/-5 millibars, the atmosphere is clear (probably hydrogen) and its Rayleigh effect is detectable. At that pressure the temperature is 2200+/-260 K.[16]

Observations by the orbiting Microvariability and Oscillations of STars telescope initially limited the planet's albedo (or reflectivity) below 30%, making it a surprisingly dark object. (The geometric albedo has since been measured to 3.8 ± 4.5%.[17]) In comparison, Jupiter has a much higher albedo of 52%. This would suggest that HD 209458 b's upper cloud deck is either made of less reflective material than is Jupiter's, or else has no clouds and Rayleigh-scatters incoming radiation like Earth's dark ocean.[18] Models since then have shown that between the top of its atmosphere and the hot, high pressure gas surrounding the mantle, there exists a stratosphere of cooler gas.[19][20] This implies an outer shell of dark, opaque, hot cloud; usually thought to consist of vanadium and titanium oxides like M dwarf stars ("pM planets"), but other compounds like tholins cannot be ruled out as of yet.[20] The Rayleigh-scattering heated hydrogen rests at the top of the stratosphere; the absorptive portion of the cloud deck floats above it at 25 millibars.[21]

Exosphere

Surrounding that level, on November 27, 2001 the Hubble Space Telescope detected sodium, the first planetary atmosphere outside our solar system to be measured.[22] This detection was predicted by Sara Seager in late 2001.[23] The core of the sodium line runs from pressures of 50 millibar to a microbar.[24] This turns out to be about a third the amount of sodium at HD 189733 b.[25]

In 2003-4, astronomers used the Hubble Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph to discover an enormous ellipsoidal envelope of hydrogen, carbon and oxygen around the planet that reaches 10,000 K. At this temperature, the Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution of particle velocities gives rise to a significant 'tail' of atoms moving at speeds greater than the escape velocity, and the planet is estimated to be losing about 100–500 million (1–5×108) kg of hydrogen per second. Analysis of the starlight passing through the envelope shows that the heavier carbon and oxygen atoms are being blown from the planet by the extreme "hydrodynamic drag" created by its evaporating hydrogen atmosphere. The hydrogen tail streaming from the planet is approximately 200,000 kilometres long, which is roughly equivalent to its diameter.

It is thought that this type of atmosphere loss may be common to all planets orbiting Sun-like stars closer than around 0.1 AU. HD 209458 b will not evaporate entirely, although it may have lost up to about 7% of its mass over its estimated lifetime of 5 billion years.[26] It may be possible that the planet's magnetic field may prevent this loss, as the exosphere would become ionized by the star, and the magnetic field would contain the ions from loss.[27]

Presumed atmospheric water vapor

On April 10, 2007, Travis Barman of the Lowell Observatory announced evidence that the atmosphere of HD 209458 b contained water vapor. Using a combination of previously published Hubble Space Telescope measurements and new theoretical models, Barman found strong evidence for water absorption in the planet's atmosphere.[2][4][28] His method modeled light passing directly through the atmosphere from the planet's star as the planet passed in front of it. However, this hypothesis is still being investigated for confirmation.

Barman drew on data and measurements taken by Heather Knutson, a student at Harvard University, from the Hubble Space Telescope, and applied new theoretical models to demonstrate the likelihood of water absorption in the atmosphere of the planet. The planet orbits its parent star every three and a half days, and each time it passes in front of its parent star, the atmospheric contents can be analyzed by examining how the atmosphere absorbs light passing from the star directly through the atmosphere in the direction of Earth.

According to a summary of the research, atmospheric water absorption in such an exoplanet renders it larger in appearance across one part of the infrared spectrum, compared to wavelengths in the visible spectrum. Barman took Knutson's Hubble data on HD 209458 b, applied to his theoretical model, and allegedly identified water absorption in the planet's atmosphere.

On April 24, the astronomer David Charbonneau, who led the team that made the Hubble observations, cautioned that the telescope itself may have introduced variations that caused the theoretical model to suggest the presence of water. He hoped that further observations would clear the matter up in the following months.[29] As of April 2007, further investigation is being conducted.

On October 20, 2009, researchers at JPL announced the discovery of water vapor, carbon dioxide, and methane in the atmosphere.[30][31]

Possible tests of fundamental physics

Given the exquisite accuracy with which its orbital period was measured, it was proposed to use HD 209458b to test general relativity. Indeed, the Einsteinian correction to the third Kepler law would be, in principle, measurable.

See also

References

- ^ Jackson, Brian; Richard Greenberg, Rory Barnes (2008). "Tidal Heating of Extra-Solar Planets". Astrophysical Journal 681 (2): 1631. arXiv:0803.0026. Bibcode 2008ApJ...681.1631J. doi:10.1086/587641.; Gregory Laughlin et al. (2005). "ON THE ECCENTRICITY OF HD 209458b". The Astrophysical Journal 629 (2): L121–L124. Bibcode 2005ApJ...629L.121L. doi:10.1086/444558.

- ^ a b Barman (2007). "Identification of Absorption Features in an Extrasolar Planet Atmosphere". The Astrophysical Journal Letters 661 (2): L191–L194. Bibcode 2007ApJ...661L.191B. doi:10.1086/518736. http://www.iop.org/EJ/article/1538-4357/661/2/L191/21561.html.

- ^ a b Ignas A. G. Snellen et al. (2010). "The orbital motion, absolute mass and high-altitude winds of exoplanet HD 209458b". Nature 465 (7301): 1049–1051. Bibcode 2010Natur.465.1049S. doi:10.1038/nature09111. PMID 20577209.

- ^ a b Water Found in Extrasolar Planet's Atmosphere - Space.com

- ^ Signs of water seen on planet outside solar system, by Will Dunham, Reuters, Tue Apr 10, 2007 8:44PM EDT

- ^ Water Identified in Extrasolar Planet Atmosphere, Lowell Observatory press release, April 10, 2007

- ^ Henry et al. IAUC 7307: HD 209458; SAX J1752.3-3138 12 November 1999, reported a transit ingress on Nov. 8. David Charbonneau et al., Detection of Planetary Transits Across a Sun-like Star, November 19, reports full transit observations on September 9 and 16.

- ^ Castellano et al.; Jenkins, J.; Trilling, D. E.; Doyle, L.; Koch, D. (March 2000). "Detection of Planetary Transits of the Star HD 209458 in the Hipparcos Data Set". The Astrophysical Journal Letters (University of Chicago Press) 532 (1): L51–L53. Bibcode 2000ApJ...532L..51C. doi:10.1086/312565. http://www.iop.org/EJ/article/1538-4357/532/1/L51/995926.html.

- ^ Notes for star HD 209458

- ^ NASA's Spitzer First To Crack Open Light of Faraway Worlds

- ^ Richardson, L. Jeremy; et al. (2007). "A spectrum of an extrasolar planet". Nature 445 (7130): 892–895. arXiv:astro-ph/0702507. Bibcode 2007Natur.445..892R. doi:10.1038/nature05636. PMID 17314975.

- ^ Rincon, Paul (23 June 2010). "'Superstorm' rages on exoplanet". BBC News London. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science_and_environment/10393633.stm. Retrieved 2010-06-24.

- ^ Winn, Joshua N. (2008). "Measuring accurate transit parameters". arXiv:0807.4929v2 [astro-ph]. doi:10.1017/S174392130802629X.

- ^ Winn et al.; Noyes, Robert W.; Holman, Matthew J.; Charbonneau, David; Ohta, Yasuhiro; Taruya, Atsushi; Suto, Yasushi; Narita, Norio et al. (2005). "Measurement of Spin-Orbit Alignment in an Extrasolar Planetary System". The Astrophysical Journal 631 (2): 1215–1226. arXiv:astro-ph/0504555. Bibcode 2005ApJ...631.1215W. doi:10.1086/432571. http://www.iop.org/EJ/article/0004-637X/631/2/1215/62644.html.

- ^ Jackson, Brian; Richard Greenberg, Rory Barnes (2008). "Tidal Heating of Extra-Solar Planets". ApJ 681 (2): 1631. arXiv:0803.0026. Bibcode 2008ApJ...681.1631J. doi:10.1086/587641.

- ^ a b A. Lecavelier des Etangs, A. Vidal-Madjar, J.-M. Désert and D. Sing (2008). "Rayleigh scattering by H in the extrasolar planet HD 209458b". Astronomy & Astrophysics 485 (3): 865–869. Bibcode 2008A&A...485..865L. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200809704.

- ^ Rowe, Jason F.; Matthews, Jaymie M.; Sara Seager; Dimitar Sasselov; Rainer Kuschnig; Guenther, David B.; Moffat, Anthony F. J.; Rucinski, Slavek M. et al. (2008). "Towards the Albedo of an Exoplanet: MOST Satellite Observations of Bright Transiting Exoplanetary Systems". arXiv:0807.1928v1 [astro-ph]. doi:10.1017/S1743921308026318.

- ^ Matthews J.,(2005), MOST SPACE TELESCOPE PLAYS `HIDE & SEEK' WITH AN EXOPLANET; LEARNS ABOUT ATMOSPHERE AND WEATHER OF A DISTANT WORLD

- ^ Ivan Hubeny; Adam Burrows (2008). "Spectrum and atmosphere models of irradiated transiting extrasolar giant planets". arXiv:0807.3588v1 [astro-ph]. doi:10.1017/S1743921308026458.

- ^ a b Ian Dobbs-Dixon (2008). "Radiative Hydrodynamical Studies of Irradiated Atmospheres". arXiv:0807.4541v1 [astro-ph]. doi:10.1017/S1743921308026495.

- ^ Sing, David K.; Vidal-Madjar, A.; Lecavelier des Etangs, A.; Desert, J. -M.; Ballester, G.; Ehrenreich, D. (2008). "Determining Atmospheric Conditions at the Terminator of the Hot-Jupiter HD209458b". arXiv:0803.1054v2 [astro-ph]. doi:10.1086/590076.

- ^ I. A. G. Snellen, S. Albrecht, E. J. W. de Mooij, and R. S. Le Poole (2008). "Ground-based detection of sodium in the transmission spectrum of exoplanet HD 209458b". Astronomy & Astrophysics 487: 357–362. Bibcode 2008A&A...487..357S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200809762. http://www.aanda.org/index.php?option=article&access=standard&Itemid=129&url=/articles/aa/abs/2008/31/aa09762-08/aa09762-08.html.

- ^ Seager et al.; Whitney, B. A.; Sasselov, D. D. (2000). "Photometric Light Curves and Polarization of Close‐in Extrasolar Giant Planets". The Astrophysical Journal 540 (1): 504–520. arXiv:astro-ph/0004001. Bibcode 2000ApJ...540..504S. doi:10.1086/309292. http://www.iop.org/EJ/article/0004-637X/540/1/504/50207.html.

- ^ Sing, David K.; Vidal-Madjar, A.; Lecavelier des Etangs, A.; Desert, J. -M.; Ballester, G.; Ehrenreich, D. (2008). "Determining Atmospheric Conditions at the Terminator of the Hot-Jupiter HD209458b". arXiv:0803.1054v2 [astro-ph]. doi:10.1086/590076.

- ^ Seth Redfield, Michael Endl, William D. Cochran and Lars Koesterke (20 January 2008). "Sodium Absorption from the Exoplanetary Atmosphere of HD 189733b Detected in the Optical Transmission Spectrum". The Astrophysical Journal Letters 673 (673): L87–L90. Bibcode 2008ApJ...673L..87R. doi:10.1086/527475.

- ^ Hébrard G., Lecavelier Des Étangs A., Vidal-Madjar A., Désert J.-M., Ferlet R. (2003), Evaporation Rate of Hot Jupiters and Formation of Chthonian Planets, Extrasolar Planets: Today and Tomorrow, ASP Conference Proceedings, Vol. 321, held 30 June] - 4 July 2003, Institut d'astrophysique de Paris, France. Edited by Jean-Philippe Beaulieu, Alain Lecavelier des Étangs and Caroline Terquem.

- ^ http://www.skyandtelescope.com/news/56620682.html

- ^ First sign of water found on an alien world - space - 10 April 2007 - New Scientist Space

- ^ J.R. Minkle (April 24, 2007). "All Wet? Astronomers Claim Discovery of Earth-like Planet". Scientific American. http://www.sciam.com/article.cfm?articleID=25A261F0-E7F2-99DF-313249A4883E6A86&chanID=sa007.

- ^ "Astronomers do it Again: Find Organic Molecules Around Gas Planet". October 20, 2009. http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/spitzer/news/spitzer-20091020.html.

- ^ "Organic Molecules Detected in Exoplanet Atmosphere". October 20, 2009. http://www.universetoday.com/2009/10/20/organic-molecules-detected-in-exoplanet-atmosphere/.

Further reading

- Charbonneau, D. (2003). "HD 209458 and the Power of the Dark Side". In Deming, Drake; Seager, Sara. Scientific Frontiers in Research on Extrasolar Planets. ASP Conference Series. 294. San Francisco: ASP. pp. 449–456. ISBN 1583811419.

- Deming, Drake; Seager, Sara; Richardson, L. Jeremy & Harrington, Joseph (2005). "Infrared radiation from an extrasolar planet". Nature 434 (7034): 740–743. arXiv:astro-ph/0503554. Bibcode 2005Natur.434..740D. doi:10.1038/nature03507. PMID 15785769.

- Fortney, J. J.; Sudarsky, D.; Hubeny, I.; Cooper, C. S.; Hubbard, W. B.; Burrows, A.; Lunine, J. I. (2003). "On the Indirect Detection of Sodium in the Atmosphere of the Planetary Companion to HD 209458". Astrophysical Journal 589 (1): 615–622. arXiv:astro-ph/0208263. Bibcode 2003ApJ...589..615F. doi:10.1086/374387.

- Holmström, M.; Ekenbäck, A.; Selsis, F.; Penz, T.; Lammer, H. & Wurz, P. (2008). "Energetic neutral atoms as the explanation for the high-velocity hydrogen around HD 209458b". Nature 451 (7181): 970–972. Bibcode 2008Natur.451..970H. doi:10.1038/nature06600. PMID 18288189.

External links

- "European astronomers observe first evaporating planet". Hubble Space Telescope. ESA/NASA. 2003-03-12. http://www.spacetelescope.org/news/html/heic0303.html. Retrieved 2008-06-28.

- "HD 209458 b". Extrasolar Visions. http://www.extrasolar.net/planettour.asp?StarCatId=normal&PlanetId=106. Retrieved 2008-06-28.

- Hogan, Jenny (2005-03-22). "Glow of alien planets glimpsed at last". NewScientist. http://www.newscientist.com/article.ns?id=dn7186. Retrieved 2008-06-28.

- "Hubble Makes First Direct Measurements of Atmosphere on World Around another Star". Hubble Space Telescope. NASA. 2001-11-27. http://hubblesite.org/newscenter/archive/releases/2001/38/text. Retrieved 2008-06-28.

- McKee, Maggie (2004-02-03). "Oxygen seen streaming off exoplanet". NewScientist. http://www.newscientist.com/article.ns?id=dn4634. Retrieved 2008-06-28.

- "NASA's Spitzer Marks Beginning of New Age of Planetary Science". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. NASA. 2005-03-22. http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.cfm?release=2005-050. Retrieved 2008-06-28.

- "Oxygen and carbon discovered in exoplanet atmosphere 'blow-off'". Hubble Space Telescope. ESA/NASA. 2004-02-02. http://www.spacetelescope.org/news/html/heic0403.html. Retrieved 2008-06-28.

- Peplow, Mark (2005-03-23). "Light from alien planets confirmed". Nature. http://www.nature.com/news/2005/050321/full/news050321-9.html. Retrieved 2008-06-28.

- AAVSO Variable Star Of The Season. Fall 2004: The Transiting Exoplanets HD 209458 and TrES-1

Categories:- Exoplanets discovered in 1999

- Extrasolar planets

- Gas giant planets

- Hot Jupiters

- Pegasus constellation

- Transiting extrasolar planets

- Exoplanets detected by radial velocity

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.