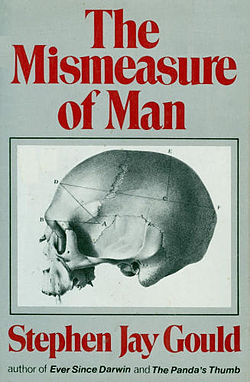

- The Mismeasure of Man

-

The Mismeasure of Man (1981), by Stephen Jay Gould, is a history and critique of the statistical methods and cultural motivations underlying biological determinism, the belief that “the social and economic differences between human groups — primarily races, classes, and sexes — arise from inherited, inborn distinctions and that society, in this sense, is an accurate reflection of biology.”[1] The principal theme of biological determinism, that “worth can be assigned to individuals and groups by measuring intelligence as a single quantity”, is analyzed in discussions of craniometry and psychological testing, two methods used to measure and establish intelligence as a single quantity. That the methods have “two deep fallacies”; the first is “reification”, which is “our tendency to convert abstract concepts into entities”, such as the intelligence quotient (IQ) and the general intelligence factor (g factor), which have been the cornerstones of much research into human intelligence; the second fallacy is '“ranking”, the “propensity for ordering complex variation as a gradual ascending scale.”

The revised and expanded, second edition of the Mismeasure of Man (1996) analyzes and challenges the methodological accuracy of The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life (1994), by Richard Herrnstein and Charles Murray, which re-presented the arguments of biological determinism, “the abstraction of intelligence as a single entity, its location within the brain, its quantification as one number for each individual, and the use of these numbers to rank people in a single series of worthiness, invariably to find that oppressed and disadvantaged groups — races, classes, or sexes — are innately inferior and deserve their status.”[2] (See: Scientific racism)

Contents

Summary

Craniometry

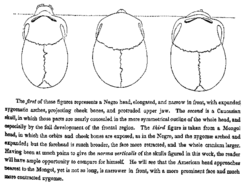

The Mismeasure of Man (1981) is a critical analysis of the early works of scientific racism about the supposed, biologically inherited (genetic) basis for human intelligence, such as craniometry, the measurement of skull volume and its relation to intellectual faculties. Gould proposed that much of the research was based more upon the racial and social prejudices of the researchers than upon their scientific objectivity; that on occasion, researchers such as Samuel George Morton (1799–1851), Louis Agassiz (1807–1873), and Paul Broca (1824–1880), committed the methodological fallacy of including their personal (a priori) expectations to the conclusions, as part of their analytical reasoning. Gould re-worked Morton’s original endocranial-volume data, and proposed that the original results were based upon biases and data manipulation; that by selectively using the data, Morton falsified the results. That when said biases are accounted, the original hypothesis — an ordering in skull volume ranging from Blacks to Mongols to Whites — is unsupported by the data.

Bias and falsification

The Mismeasure of Man presents an historical evaluation of the concepts of the intelligence quotient (IQ) and of the general intelligence factor (g factor), which were and are the measures for intelligence used by psychologists. Gould proposed that most psychological studies have been heavily biased, by the belief that the human behavior of a race of people is best explained by genetic heredity. He cites the Burt Affair, about the allegedly fraudulent, oft-cited twin studies, by Cyril Burt (1883–1971), wherein he claimed that human intelligence is highly heritabile.

Statistical correlation and heritability

As a scientist (evolutionary biologist paleontologist) and historian of science, Stephen Jay Gould accepted biological variability (the premise of the transmission of intelligence via genetic heredity), but opposed biological determinism, which posits that genes determine a definitive, unalterable social destiny for each man and each woman in life and society. The Mismeasure of Man (1981) is an analysis of statistical correlation, the mathematics applied by psychologists to establish the validity of IQ tests, and the heritability of intelligence. For example, to establish the validity of the proposition that IQ is supported by a general intelligence factor (g factor), the answers to several tests of cognitive ability must positively correlate; thus, for the g factor to be a heritable trait, the IQ-test scores of close-relation respondents must correlate more than the IQ-test scores of distant-relation respondents. Hence, correlation does not imply causation; in example, Gould said that the measures of the changes, over time, in “my age, the population of México, the price of Swiss cheese, my pet turtle’s weight, and the average distance between galaxies” have a high, positive correlation — yet that correlation does not indicate that Gould’s age increased because the Mexican population increased. More specifically, a high, positive correlation between the intelligence quotients of a parent and a child can be presumed either as evidence that IQ is genetically inherited, or that IQ is inherited through social and environmental factors. Moreover, because the data from IQ tests can be applied to arguing the logical validity of either proposition — genetic inheritance and environmental inheritance — the psychometric data have no inherent value.

Gould proposed that if the genetic heritability of IQ were demonstrable within a given racial or ethnic group, it would not explain the causes of IQ differences among the people of a group, or if said IQ differences can be attributed to the environment. For example, the height of a person is genetically determined, but there exist height differences within a given social group that can be attributed to environmental factors (e.g. the quality of nutrition) and to genetic inheritance. The evolutionary biologist Richard Lewontin, a colleague of Gould’s, is a proponent of said argument in relation to the cognitive ability tests that determine a person’s intelligence quotient. An example of the intellectual confusion about what heritability is and is not, is the statement: “If all environments were to become equal for everyone, heritability would rise to 100 percent because all remaining differences in IQ would necessarily be genetic in origin”, which Gould said is misleading, at best, and false, at worst.[3] First, it is very difficult to conceive of a world wherein every man, woman, and child grew up in the same environment, because their spatial and temporal dispersion upon the planet Earth makes it impossible. Second, were people to grew up in the same environment, not every difference would be genetic in origin, because of the randomness of molecular and genetic development. Therefore, heritability is not a measure of phenotypic (physiognomy and physique) differences among racial and ethnic groups, but of differences between genotype and phenotype in a given population.

Furthermore, he dismissed the proposition that an IQ score measures the general intelligence (g factor) of a person, because cognitive ability tests (IQ tests) present different types of questions, and the responses tend to form clusters of intellectual acumen. That is, different questions, and the answers to them, yield different scores — which indicate that an IQ test is a combination method of different examinations of different things. As such, Gould proposed that IQ-test proponents assume the existence of “general intelligence” as a discrete quality within the human mind, and thus they analyze the IQ-test data to produce an IQ number that establishes the definitive general intelligence of each man and of each woman. Hence, Dr. Gould dismissed the IQ number as an erroneous artifact of the statistical mathematics applied to the raw IQ-test data; especially because psychometric data can be variously analyzed to produce multiple IQ scores.

Reception

Praise

As an author, Stephen Jay Gould said that the most positive review of the first edition of The Mismeasure of Man (1981) was by the British Journal of Mathematical & Statistical Psychology, which reported that “Gould has performed a valuable service in exposing the logical basis of one of the most important debates in the social sciences, and this book should be required reading for students and practitioners alike.”[4] In the New York Times newspaper, the journalist Christopher Lehmann-Haupt said that the critique of factor analysis “demonstrates persuasively how factor analysis led to the cardinal error in reasoning, of confusing correlation with cause, or, to put it another way, of attributing false concreteness to the abstract.”[5] The British journal Saturday Review praised the book as a “fascinating historical study of scientific racism”, and that its arguments “illustrate both the logical inconsistencies of the theories and the prejudicially motivated, albeit unintentional, misuse of data in each case.”[6] In the American Monthly Review magazine, Richard York and the sociologist Brett Clark praised the book’s thematic concentration, saying that “rather than attempt a grand critique of all ‘scientific’ efforts aimed at justifying social inequalities, Gould performs a well-reasoned assessment of the errors underlying a specific set of theories and empirical claims.”[7]

Awards

The first edition of The Mismeasure of Man (1981) won the non-fiction award from the National Book Critics Circle; the Outstanding Book Award for 1983 from the American Educational Research Association; the Italian translation was awarded the Iglesias prize in 1991; and in 1998, the Modern Library ranked it as the 24th-best non-fiction book of all time.[8] In December 2006, Discover magazine ranked The Mismeasure of Man as the 17th-greatest science book of all time.[9]

Criticism

Miscalculation

In a study published in 1988, John S. Michael reported that Samuel G. Morton’s original 19th-century data were more accurate than Gould had described; that “contrary to Gould’s interpretation . . . Morton’s research was conducted with integrity”. Nonetheless, Michael's analysis suggested that there were discrepancies in Morton’s craniometric calculations.[10] In another study, published in 2011, Jason E. Lewis and colleagues re-measured the cranial volumes of the skulls in Morton’s collection, and re-examined the respective statistical analyses by Morton and by Gould, concluding that, contrary to Gould’s analysis, Morton did not falsify craniometric research results to support his racial and social prejudices, and that the "Caucasians" possessed the greatest average cranial volume in the sample. To the extent that Morton’s craniometric measurements were erroneous, the error was away from his personal biases. Ultimately, Lewis and colleagues disagreed with most of Gould’s criticisms of Morton, finding that Gould’s work was “poorly supported”, and that, in their opinion, the confirmation of the results of Morton’s original work “weakens the argument of Gould, and others, that biased results are endemic in science.” Nonetheless, they concluded that, “While we differ with Gould in regards to his analysis of Morton, we find other things to admire in Gould’s body of work.”[11]

Misrepresentation

In a review of The Mismeasure of Man, Bernard Davis, professor of microbiology at Harvard Medical School, said that Gould erected a straw man argument based upon incorrectly defined key terms — specifically reification — which Gould furthered with a “highly selective” presentation of statistical data, all motivated more by politics than by science.[12] That Philip Morrison’s laudatory book review of The Mismeasure of Man in Scientific American, was written and published because the editors of the journal had “long seen the study of the genetics of intelligence as a threat to social justice.” Davis also criticized the popular-press and the literary-journal book reviews of The Mismeasure of Man as generally approbatory; whereas, most scientific-journal book reviews were generally critical. Nonetheless, in 1994, Gould contradicted Davis by arguing that of twenty-four academic book reviews written by experts in psychology, fourteen approved, three were mixed opinions, and seven disapproved of the book.[13] Furthermore, Davis accused Gould of having misrepresented a study by Henry H. Goddard (1866–1957) about the intelligence of Jewish, Hungarian, Italian, and Russian immigrants to the U.S., wherein Gould reported Goddard’s qualifying those people as “feeble-minded”; whereas, in the initial sentence of the study, Goddard said the study subjects were atypical members of their ethnic groups, who had been selected because of their suspected sub-normal intelligence. Countering Gould, Davis further explained that Goddard proposed that the low IQs of the sub-normally intelligent men and women who took the cognitive-ability test likely derived from their social environments rather than from their respective genetic inheritances, and concluded that “we may be confident that their children will be of average intelligence, and, if rightly brought up, will be good citizens.”[14]

Intellectual error

In his review, psychologist John B. Carroll said that Gould did not understand “the nature and purpose” of factor analysis.[15] Statistician David J. Bartholomew, of the London School of Economics, said that Dr. Gould erred in his use of factor analysis, irrelevantly concentrated upon the fallacy of reification (the abstract as concrete thing), and ignored the contemporary scientific consensus about the existence of the psychometric general intelligence factor (g factor).[16][17]

Propaganda

Reviewing the book, Stephen F. Blinkhorn, a senior lecturer in psychology at the University of Hertfordshire, wrote that The Mismeasure of Man was “a masterpiece of propaganda” that selectively juxtaposed data to further a political agenda.[18] Psychologist Lloyd Humphreys, then editor-in-chief of The American Journal of Psychology and Psychological Bulletin, wrote that The Mismeasure of Man was “science fiction” and “political propaganda”, and that Gould had misrepresented the views of Alfred Binet, Godfrey Thomson, and Lewis Terman.[19]

In his review, psychologist Franz Samelson wrote that Gould was wrong in asserting that the psychometric results of the intelligence tests administered to soldier-recruits by the U.S. Army contributed to the legislation of the Immigration Restriction Act of 1924.[20] In their study of the Congressional Record and committee hearings related to the Immigration Act, Mark Snyderman and Richard J. Herrnstein reported that “the [intelligence] testing community did not generally view its findings as favoring restrictive immigration policies like those in the 1924 Act, and Congress took virtually no notice of intelligence testing.”[21]

Responses by subjects of the book

In his review ofThe Mismeasure of Man, Arthur Jensen, a University of California (Berkeley) educational psychologist whom Gould much criticized in the book, wrote that Gould used straw man arguments to advance his opinions, misrepresented other scientists, and propounded a political agenda. According to Jensen, the book was “a patent example” of the bias that political ideology imposes upon science — the very thing that Gould sought to portray in the book. Jensen also criticized Gould for concentrating on long-disproven arguments, rather than addressing “anything currently regarded as important by scientists in the relevant fields”, suggesting that drawing conclusions from early human intelligence research is like condemning the contemporary automobile industry based upon the mechanical performance of the Ford Model T.[22]

Charles Murray, co-author of The Bell Curve (1994), said that his views about the distribution of human intelligence, among the races and the ethnic groups who compose the U.S. population, were misrepresented in The Mismeasure of Man.[23]

Psychologist Hans Eysenck wrote that The Mismeasure of Man is a book that presents a “a paleontologist’s distorted view of what psychologists think, untutored in even the most elementary facts of the science.”[24]

Responses to the second edition (1996)

Arthur Jensen and Bernard Davis argued that if the g factor (general intelligence factor) were replaced with a model that tested several types of intelligence, it would change results less than one might expect. Therefore, according to Jensen and Davis, the results of standardized tests of cognitive ability would continue to correlate with the results of other such standardized tests, and that the intellectual achievement gap between black and white people would remain.[22]

Psychologist J. Philippe Rushton accused Stephen J. Gould of “scholarly malfeasance” for misrepresenting and for ignoring contemporary scientific research pertinent to the subject of his book, and for attacking dead hypotheses and methods of research. He faulted The Mismeasure of Man because it did not mention the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies that showed the existence of statistical correlations among brain-size, IQ, and the g factor, despite Rushton having sent copies of the MRI studies to Gould. Rushton further criticized the book for the absence of the results of five studies of twins reared corroborating the findings of Cyril Burt — the contemporary average was 0.75 compared to the average of 0.77 reported by Burt.[25]

James R. Flynn, a researcher critical of racial theories of intelligence, repeated the arguments of Arthur Jensen about the second edition of The Mismeasure of Man. Flynn wrote that “Gould’s book evades all of Jensen’s best arguments for a genetic component in the black–white IQ gap, by positing that they are dependent on the concept of g as a general intelligence factor. Therefore, Gould believes that if he can discredit g no more need be said. This is manifestly false. Jensen’s arguments would bite no matter whether blacks suffered from a score deficit on one or ten or one hundred factors.”[26]

According to psychologist Ian Deary, Gould's claim that there is no relation between brain size and IQ is outdated. Furthermore, he reported that Gould refused to correct this in new editions of the book, even though newly available data were brought to his attention by several researchers.[27]

See also

- History of the race and intelligence controversy

External links

Praise

- "Debunking as Positive Science" by Richard York and Brett Clark

- "The Mismeasure of Man." by John H. Lienhard, NPR, The Engines of Our Ingenuity.

- "The Mismeasure of Man" by Martin A. Silverman and Ilene Silverman, Psychoanalytic Quarterly

- "Intelligence and Some of its Testers" by Franz Samelson, Science

- "Review of The Mismeasure of Man" by Karen Murphy

Criticism

- "Reflections on Stephen Jay Gould's The Mismeasure of Man" by John B. Carroll

- "The Mismeasures of Gould" by J. Philippe Rushton, National Review

- "Race, Intelligence, and the Brain" by J. Philippe Rushton

- "The Debunking of Scientific Fossils and Straw Persons" by Arthur Jensen

- "Neo-Lysenkoism, IQ and the press" by Bernard Davis, The Public Interest

- Scientists Measure the Accuracy of a Racism Claim, New York Times, June 13, 2011.

Further reading

- Goodfield, June (1981). "A mind is not described in numbers." The New York Times Book Review (Nov. 1): 11.

- Gould, S. J. (1984). "Human Equality Is a Contingent Fact of History." Natural History 93 (Nov.): 26-33.

- Gould, S. J. (1994). "Curveball: Review of The Bell Curve." The New Yorker 70 (Nov. 28): 139-149.

- Gould, S. J. (1995). "Ghosts of Bell Curves Past." Natural History 104 (Feb.): 12-19.

- Janik, Allan (1983). "The Mismeasure of Man." Ethics 94 (1): 153–155.

- Junker, Thomas (1998). "Blumenbach's Racial Geometry." Isis 89 (3): 498–501.

- Korb, K. B. (1994). "Stephen Jay Gould on Intelligence." Cognition 52 (2): 111-23.

- Leach, Sir Edmund (1982). "Review: The Mismeasure of Man." New Scientist 94 (May 13): 437.

- Lewis J. E. et al. (2011) "The Mismeasure of Science: Stephen Jay Gould versus Samuel George Morton on Skulls and Bias." PLoS Biol 9(6): e1001071.

- Oeijord, Nils K. (2003). Why Gould Was Wrong. iUniverse.com.

- Ravitch, Diane (2008). "The Mismeasure of Man." Commentary 73 (June).

- Sulloway, Frank (1997). "Still Mismeasuring Man." Skeptic 5 (1): 84.

References

- ^ Gould, S. J. (1981). The Mismeasure of Man. New York: W.W. Norton & Co. p. 20.

- ^ Gould, S. J. (1981). The Mismeasure of Man pp. 24–25.

- ^ Gottfredson, Linda (1994). "Mainstream Science on Intelligence." Wall Street Journal 13 December, p. A18.

- ^ Gould, S. J. (1994). The Mismeasure of Man: Revised edition. New York: W.W. Norton & Co. p. 45.

- ^ Lehmann-Haupt, Christopher (1981). "Books of the Times"

- ^ Saturday Review (October 1981 pg. 74)

- ^ York, R., and B. Clark (2006). "Debunking as Positive Science." Monthly Review 57 (Feb.):315.

- ^ American Library (1998). 100 "Best Nonfiction." July 20.

- ^ Discover Editors (2006). "25 Greatest Science Books of All Time." Discover 27 (Dec. 8).

- ^ Michael, J. S. (1988). "A New Look at Morton's Craniological Research." Current Anthropology 29: 349-354.

- ^ Lewis, Jason E.; Degusta, David; Meyer, Marc R.; Monge, Janet M.; Mann, Alan E.; Holloway, Ralph L. (2011), "The Mismeasure of Science: Stephen Jay Gould versus Samuel George Morton on Skulls and Bias", PLoS Biol 9: e1001071+, doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001071, http://www.plosbiology.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pbio.1001071, retrieved 2011-06-08

- ^ Davis, Bernard (1983). "Neo-Lysenkoism, IQ and the press." The Public Interest 74 (2): 41-59.

- ^ Gould, Stephen Jay (1994). "The mismeasure of Man." [Second edition] 1994:45.

- ^ Davis, Bernard (1983). "Neo-Lysenkoism, IQ and the press." The Public Interest 74 (2): 45.

- ^ Carroll, J. B. Reflections on Stephen Jay Gould's The Mismeasure of Man (1981). (1995). Intelligence, 21, 121-134.

- ^ Bartholomew, D. J. (2004). Measuring Intelligence, Facts and Fallacies. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. p. 73.

- ^ Bartholomew, D. J. (2004). Measuring Intelligence, Facts and Fallacies. p. 145-46.

- ^ Blinkhorn, Steve (1982). "What Skulduggery?" Nature 296 (April 8): 506.

- ^ Humphreys, L. (1983). Review of The Mismeasure of Man by Stephen Jay Gould. American Journal of Psychology 96, pp. 407–415.

- ^ Samelson, F. (1982). "Intelligence and Some of its Testers." Science 215 (Feb. 5): 656–657.

- ^ Snyderman, M. and Herrnstein, R. J. (1983). Intelligence Tests and the Immigration Act of 1924. American Psychologist, pp. 986–995.

- ^ a b Jensen, Arthur (1982). "The Debunking of Scientific Fossils and Straw Persons" Contemporary Education Review 1 (2): 121- 135.

- ^ Miele, Frank (1995). "For Whom the Bell Curve Tolls." Skeptic 3 (2):34-41.

- ^ Eysenck, Hans (1998). Intelligence – A New Look. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, p. 3.

- ^ Rushton, J. P. (1997). "Race, Intelligence, and The Brain." Personality and Individual Differences 23:169-180.

- ^ Flynn, J. R. (1999). Evidence against Rushton: The Genetic Loading of the Wisc-R Subtests and the Causes of Between-Group IQ Differences. Personality and Individual Differences 26, pp. 373–393.

- ^ Deary, I. J. (2001). Intelligence: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 125.

Books by Stephen Jay Gould General An Urchin in the Storm · The Mismeasure of Man · Time's Arrow, Time's Cycle · Wonderful Life · Full House · Questioning the Millennium · Rocks of Ages · The Hedgehog, the Fox, and the Magister's Pox

Essay collections

in Natural HistoryTechnical Categories:- 1981 books

- Biology books

- Books by Stephen Jay Gould

- Psychology books

- Race and intelligence controversy

- Eugenics

- National Book Critics Circle Award winner

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.