- Dumnonia

-

This article is about the kingdom in Southwestern Britain. For Brythonic colony of the same name in Brittany, see Domnonée. For the kingdom in northern Britain, see Damnonii.

Dumnonia is the Latinised name for the Brythonic kingdom in sub-Roman Britain between the late 4th and late 8th centuries, located in the farther parts of the south-west peninsula of Great Britain. It was centred in the area later known as Devon, but also included parts of Somerset and possibly Dorset, its eastern boundary changing over time.

Cadbury Castle, Somerset

Cadbury Castle, Somerset

Some historians interpreted it as including Cornubia or Cornwall, although the kingdom of Cornwall was based on a sub-tribe, the Cornovii, and appears to have been at least semi-independent at times, certainly retaining its independence after parts of Dumnonia came under Anglo-Saxon control between the 7th and 10th centuries.[1]

Contents

Name

The kingdom is named after the Dumnonii, a British Celtic tribe living in the southwest when the Romans arrived in Britain, according to Ptolemy's Geography. Variants of the name Dumnonia include Domnonia and Damnonia, the latter being used by Gildas in the 6th century as a pun on "damnation" to deprecate the area's contemporary ruler Constantine.[2] The name has etymological origins in the proto-Celtic root word *dubno-, meaning both "deep" and "world". Groups with similar names existed in Scotland (Damnonii) and Ireland (Fir Domnann).[2] Later, the area became known to the English of neighbouring Wessex as the kingdom of West Wales, and its inhabitants were also known to them as Defnas (i.e. men of Dumnonia). In Welsh, and similarly in the native Brythonic language, it was Dyfneint and this is the form which survives today in the name of the county of Devon (Modern Welsh: Dyfnaint, Cornish: Dewnans).

After emigration from southwestern Britain to northern Armorica, a sister kingdom also called Domnonia (Breton: Dumnonea, French: Domnonée) was established on the continental north Atlantic coast in what became known as Brittany (Breton: Breizh, French Bretagne, "Britain"), the name of which derives from the French Grande-Bretagne coined to distinguish the island from Bretagne. The main period of emigration from Dumnonia to Armorica is believed to have been in the 5th and 6th centuries, and it is speculated that the Dumnonii saw the end of the Roman empire as an opportunity to establish control in new areas.[3]

Extent

Before the arrival of the Romans, the Dumnonii seem to have inhabited the southwest peninsula of Britain as far east as the River Parrett in Somerset and the River Axe in Dorset, judging by the coin distributions of the Dobunni and Durotriges.[4] In the Roman period there was a provincial boundary between the area governed from Exeter and those governed from Dorchester and Ilchester.

In the post Roman period the eastern boundary of Dumnonia is unclear. The boundary may have been formed by the West Wansdyke, Selwood Forest and Bokerly Dyke. Thus Dumnonia would have included later Cornwall, Devon, most of Somerset and most of Dorset. If so Dumnonia would have included places such as Glastonbury and South Cadbury. With the expansion of Wessex, the boundary was gradually pushed westward, see below.

Culture and industries

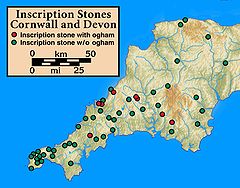

The cultural connections of the pre-Roman Dumnonii, as expressed in their ceramics, are thought to have been with the peninsula of Armorica across the Channel, and with Wales and Ireland, rather than with the southeast of Britain.[3][5][6] The people of Dumnonia are likely to have spoken a Brythonic dialect similar to the ancestor of modern Cornish and Breton. Irish immigrants, the Déisi, are evidenced by the Ogham-inscribed stones:[7][8] they have left behind, confirmed and supplemented by place-name studies. Apart from fishing and agriculture, the main economic resource of the Dumnonii was tin mining, the tin having been exported since ancient times from the port of Ictis [9] (St Michael's Mount or Mount Batten). Tin working continued throughout Roman occupation and appears to have reached a peak during the 3rd century AD.[10] The area maintained trade links with Gaul and the Mediterranean after the Roman withdrawal, and it is likely that tin played an important part in this trade.[2] Post-Roman imported pottery has been excavated from many sites across the region. An apparent surge in late 5th century Mediterranean and/or Byzantine imports is yet to be explained satisfactorily.[11]

Christianity seems to have survived in Dumnonia after the Roman departure from Britain, with a number of late Roman Christian cemeteries extending into the post-Roman period.[3] In the 5th and 6th centuries the area was allegedly evangelized by the children of Brychan and saints from Ireland, like Saint Piran; and Wales, like Saint Petroc or Saint Keyne. There were important monasteries at Bodmin and Glastonbury; and also Exeter where 5th century burials discovered near the cathedral probably represent the cemetery of the foundation attended by St. Boniface (although whether this was Saxon or Brythonic is somewhat controversial). Sporadically, Cornish bishops are named in various records until they submitted to the See of Canterbury in the mid-9th century. Parish organisation was a later development of fully Normanised times.[12]

Settlements

In pre-Roman times the Dumnonii had mostly a subsistence economy with no dominant elites, and many individual farms. Around AD 55, the Romans established a legionary fortress at Isca Dumnoniorum, modern Exeter, but west of Exeter the area remained largely un-Romanized.[9] Most of Dumnonia is notable for its lack of a villa system though there were substantial numbers south of Bath and around Ilchester, and for its many settlements that have survived from the Romano-British period. As in other Brythonic areas, Iron Age hillforts, such as Cadbury Castle, were refortified in Post-Roman times for the use of chieftains or kings, and other high-status settlements such as Tintagel seem to have been reconstructed during the period. Local archaeology has revealed that the isolated enclosed farmsteads known locally as rounds seem to have survived the Roman departure from Britain, but were subsequently replaced, in the 6th and 7th centuries, by unenclosed farms taking the Brythonic toponymic tre-.[1][13]

Exeter, known to the British as Caer Uisc, was later the site of an important Saxon minster, but was still partially inhabited by Dumnonian Britons up until the 10th century when Athelstan expelled them.[3][14] By the mid-9th century, the royal seat may have been relocated further west, during the West Saxon advance, to Lis-Cerruyt (modern Liskeard). Cornish earls in the 10th century were said to have moved to Lostwithiel after Liskeard was seized.[15] It has been suggested that the rulers of Dumnonia were itinerant, stopping at various royal residences, such as Tintagel and Cadbury Castle, at different times of the year, possibly simultaneously holding lands in Brittany across the Channel. There is textual and archaeological evidence that districts such as Trigg were used as martially points for 'war hosts' from across the region,[16] likely to have also included troops from overseas evidenced by corresponding place names in Brittany—a recurring motif of Brythonic Arthurian myth originating in this period, such as Tristan and Iseult.

History and rulers

Main article: Kings of DumnoniaAlthough subjugated by about AD 78, the local population could have retained strong local control, and Dumnonia may have been self-governed under Roman rule.[14] Geoffrey of Monmouth stated that the ruler of Dumnonia, perhaps about the period c290–c305, was Caradoc (Caractacus), who was said to have been the trusted advisor of Eudaf Hen (Octavius the Old). If not an entirely legendary figure, Caradoc would not have been a king in the true sense but may have held a powerful office within the Roman administration.[17] It is possible that the "Caratacus Stone"[18] on Withypool Common near Dulverton, inscribed Carataci nepus--- ("relative of Caradoc"), records one of his co-lateral descendants.

After the Roman withdrawal, Dumnonia's domestic history is obscure, though its geographical position enabled it to survive for centuries.[5] The post-Roman history of Dumnonia comes from a variety of sources and is considered exceedingly difficult to interpret[19] given that historical fact, legend and confused pseudo-history are compounded by a variety of sources in Middle Welsh and Latin. The main sources available for discussion of this period include Gildas's De Excidio Britanniae and Nennius's Historia Brittonum, the Annales Cambriae, Anglo Saxon Chronicle, William of Malmesbury's Gesta Regum Anglorum and De Antiquitate Glastoniensis Ecclesiae, along with texts from the Black Book of Carmarthen and the Red Book of Hergest, and Bede's Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum as well as "The Descent of the Men of the North" (Bonedd Gwŷr y Gogledd, in Peniarth MS 45 and elsewhere) and the Book of Baglan.

Arthurian connections

King Arthur is often said to have been a member of the royal house of Dumnonia, his traditional grandfather, Constantine, being identified with the Constantine denounced by Gildas as the "tyrant whelp of the filthy lioness of Damnonia".[3][5] Geoffrey of Monmouth said that Arthur was conceived at Tintagel Castle.[20] Erbin and his son, Geraint (or Gerren), appear in the Arthurian tale of Geraint and Enid as ruling "on the far side of Severn" (from Caerleon). There is debate about where Arthur's great victory at the Battle of Mount Badon, where the Brythonic Dumnonians fought off Anglo-Saxons, took place. Most historians, however, believe this battle was fought elsewhere, such as at Bath. Geoffrey of Monmouth claimed that Arthur's final Battle of Camlann, was fought in Cornwall; tradition points to Slaughter Bridge near Camelford.[21]

Conflict with the Saxons

The Britons in Dumnonia were cut off from their allies in Wales by Ceawlin of Wessex's victory at Dyrham in 577, but as sea travel was easier than travel by land, the blow may not have been severe; principal trade routes were apparently maintained via the sea ports of neighbouring Brittany, since absorbed into France.[5] Clemen is thought to have been king when the Britons fought the Battle of Beandun (possibly Bindon near Axmouth in Devon[22]) in 614. However, Bampton in Oxfordshire has also been identified as the site of the battle.[23] The former battle site suggests that the Dumnonian army was invading Wessex using the Roman road eastward from Exeter to Dorchester and was intercepted by a West Saxon garrison marching south.[24]

The Flores Historiarum, attributed incorrectly to Matthew of Westminster, states that the Britons were still in possession of Exeter in 632, when it was bravely defended against Penda of Mercia until relieved by Cadwallon, who engaged and defeated the Mercians with "great slaughter to their troops".[25] However this is based on Geoffrey of Monmouth's pseudo-history.[26]

Around 652 Cenwalh of Wessex made a breakthrough against the Dumnonian defensive lines at the battle of Bradford-upon-Avon. The West Saxon victory at the Battle of Peonnum (possibly modern Penselwood in east Somerset), around 658, resulted in the Saxons capturing "as far as the Parrett" and the eastern part of Dumnonia being permanently annexed by Wessex. The Saxons may have expanded westward from eastern Somerset after a battle in 661 at Posentesburh, possibly Posbury near Crediton in Devon. In 682 they "advanced as far as the sea", but it is unclear where this was. In 705 a bishopric was set up in Sherborne for the Saxon area west of Selwood. In 710 a battle was fought between Geraint of Dumnonia and King Ine of Wessex.

The Annales Cambriae claim a heavy defeat of a Saxon force in Cornwall in 722. By about 755, the territory of the "Defnas" was coming under significant pressure from the Saxon army. The campaigns of Egbert of Wessex in Devon between 813 and 822 probably signalled the conquest of insular Dumnonia leaving a rump state in what is today called Cornwall.[27] The Cornish bishop of Bodmin acknowledged the authority of Canterbury in 870 and the last known Cornish King, Dunyarth, died in 875. The east bank of the Tamar was fixed by Æthelstan as the boundary between Cornwall and Devon in 936.

Possible Dumnonian continuity in Cornwall and Brittany

Main article: Kingdom of CornwallDumnonia was sufficiently part of the known world for Aldhelm, later bishop of Sherborne, to address a letter around 680, to its king Geraint regarding the date of Easter, and though Geraint was defeated by Ine of Wessex around 710, the kingdom survived.[5] However, by about 813, Dumnonia was so compressed by the inroads made by Wessex that it had effectively ceased to exist as such. The remaining British territory became known as Cerniu, Cernyw, or Kernow, and to the Anglo-Saxons as Cornwall or "West Wales".

Egbert of Wessex had further victories in the area in 813.[28] In 822 a battle was fought between the "Welsh", presumably those of Cornwall, and the Anglo-Saxons. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle states:- "The Westwealas (Cornish) and the men of Defnas (Devon) fought at Gafulforda" (perhaps Galford in west Devon). However, there is no mention of who won or who lost, or whether the men of Cornwall and Devon were fighting each other or on the same side. A further rebellion in 838, when the "West Welsh" were supported by Danish forces, was crushed by Egbert at Hingston Down, located either near Gunnislake or alternatively near Moretonhampstead.[5] By the 880s Wessex had gained control of at least part of Cornwall, where Alfred the Great had estates.[29] In 927, according to William of Malmesbury writing around 1120, Athelstan evicted the Cornish from Exeter and perhaps the rest of Devon: "Exeter was cleansed of its defilement by wiping out that filthy race".[30] In 936 he set the border between England and Cornwall as the east bank of the River Tamar.[31]

Although the chronology of Wessex expansion into all of Dumnonia is unclear, Devon had long been absorbed into England by the reign of Edward the Confessor.[32][33] In the period up to the Norman Conquest of 1066 there are references to a ruler Cadoc of Cornwall. This last native Earl of Cornwall was deposed by William the Conqueror, effectively bringing to a close the last vestiges of the Dumnonian kings in Britain. However, Cornwall showed a very different type of settlement pattern to that of Wessex and places continued, even after 1066, to be named in the Celtic Cornish tradition with Saxon architecture being uncommon in Cornwall. The earliest record for any Anglo Saxon place names west of the Tamar is around 1040.[30]

The region of Cornouaille (Br. Kernev) in modern France is assumed to owe its name to descendants originating in insular Cornwall—the medieval kingdom of Domnonea, cognate to ancient Dumnonia, has however been lost to modern departemente boundaries.

See also

- Dumnonii

- Kings of Dumnonia

- Kingdom of Cornwall

- Legendary Dukes of Cornwall, for the pseudo-historic rulers of Cornwall mentioned by Geoffrey of Monmouth

- History of Cornwall

- History of Brittany

- Domnonia

- Domnonee

- Cornouaille

References

- ^ a b Pearce, Susan M. (1978), The Kingdom of Dumnonia: Studies in History and Tradition in South-Western Britain A.D. 350-1150 Padstow: Lodenek Press.

- ^ a b c John T. Koch, Celtic Culture: a historical encyclopaedia, 2006

- ^ a b c d e Yorke, Barbara, Wessex in the early Middle Ages, 1995

- ^ Jones, Barri; Mattingly, David (1990), "Britain Before the Conquest: Urbanization", An Atlas of Roman Britain, Cambridge: Blackwell Publishers (published 2007), pp. 47–55, ISBN 9781842170670

- ^ a b c d e f Cannon, J.A., Kingdom of Dumnonia, in The Oxford Companion to British History, 2002

- ^ Cunliffe, Barry (2005). Iron Age Communities in Britain: an Account of England, Scotland and Wales from the Seventh Century BC Until the Roman Conquest (4th ed.). New York: Routledge. pp. 201–206. ISBN 0415347793..

- ^ Thomas, Charles (1994). And Shall These Mute Stones Speak? Post-Roman Inscriptions in Western Britain. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ISBN 0708311601.

- ^ The stones are sometimes inscribed in Latin, sometimes in both: Thomas (1994).

- ^ a b Roman-Britain.org The Dumnonii. Retrieved on 2007-11-25.

- ^ A history of Cornish mining

- ^ Thomas, Charles (1981) reviewing Pearce (1978) in Britannia 12; p. 417

- ^ Pearce (1978), ch. 3 "The Establishment of the Church".

- ^ Kain, Roger; Ravenhill, William (eds.) (1999) Historical Atlas of South-West England. Exeter / provides detailed information

- ^ a b Snyder, Christopher A. (2003). The Britons. Blackwell. ISBN 0631222606.

- ^ Whitaker, John (1804). The Ancient Cathedral of Cornwall, Historically Surveyed. London. p. 48.

- ^ Morris, John (1973). The Age of Arthur: a history of the British Isles from 350 to 650. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 0297176013.

- ^ Caradoc, 'King' of Dumnonia

- ^ http://everythingexmoor.org.uk/page.php?id=164

- ^ Webster, Graham (1991) The Cornovii (Peoples of Roman Britain series)

- ^ *Thomas, Charles (1993) English Heritage Book of Tintagel: Arthur and archaeology. London: B. T. Batsford; pp. 23-28

- ^ Slaughterbridge is said to take its name from two battles which reputedly took place nearby during the Early Middle Ages ( http://www.slaughterbridgedig.blogspot.com/ Archeologist Nick Hanks' website ). As 'slaughter' is an Old English word for 'marsh' it provides no evidence that battles were fought here (see Galford for the battle of Gafulford).

- ^ Morris, John (1995) The Age of Arthur ISBN 1-84212-477-3; p. 307

- ^ Victoria County History, OxfordshireDumnonia

- ^ Morris, John (1995) The Age of Arthur ISBN 1-824212-477-3; p. 308

- ^ Jenkins, Alexander (1806) The History and Description of the City of Exeter. Exeter: P. Hedgeland; p. 11

- ^ Giles, J. A. (1848) Six Old English Chronicles. London: Henry G. Bohn; p. 284

- ^ Major, Albany (1913) Early Wars of Wessex, pp. 92-98. Cambridge: University Press (reissued by: Blandford Press. ISBN 0713720689)

- ^ Major, Albany (1913) Early Wars of Wessex, pp. 95. Blandford Press. ISBN 0713720689.

- ^ Keynes, Simon; Lapidge, Michael (tr.) (1983) Alfred the Great - Asser's Life of King Alfred and other contemporary sources, London, Penguin, p. 175; cf. ibid, p. 89.

- ^ a b Payton, Philip (1996) Cornwall. Fowey: Alexander Associates

- ^ Cornwall timeline 936

- ^ Williams, Ann; Martin, G. H. (2002) (tr.) Domesday Book - a complete translation, London, Penguin; pp. 341-357

- ^ Swanton, Michael (tr.) (2000) The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, (2nd ed.) London, Phoenix Press; p.177

Categories:- Former countries in the British Isles

- History of Devon

- History of Somerset

- History of Cornwall

- Sub-Roman Britain

- West Country

- South West England

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.