- Mangalorean regionalism

-

Mangalorean regionalism centers on increasing Tulu Nadu's influence and political power through the formation of a separate Tulu Nadu state from Karnataka. Tulu Nadu is a region on the south-western coast of India. It consists of the Dakshina Kannada and Udupi districts of Karnataka, and the northern parts of the Kasargod district up to the Chandragiri river in Kerala.[1] The Chandragiri river is traditionally considered to be a boundary between Tulu Nadu and Kerala.[2][3] Mangalore is the largest and the chief city of Tulu Nadu. Tulu activists have been demanding a separate Tulu Nadu state since the 1990s, considering language and culture as the basis for their demand.[1][4][5][6][7]

Tulu Nadu was ruled by several major Kannada powers, including the Kadambas, Alupas, Vijayanagar dynasty, and the Keladi Nayakas.[8] The region was unified with the state of Mysore (now called Karnataka) in 1956.[9] The region encompassing Tulu Nadu is also known as South Canara.[10] Tulu Nadu is demographically and linguistically diverse with several languages, including Tulu, Konkani, Kannada, and Beary commonly spoken and understood.[11][12][13]

Contents

Distinct identity

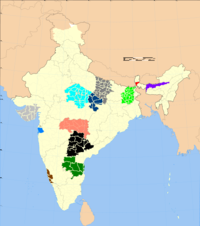

Tulu Nadu (in brown) is shown with other aspirant states of India

.

According to the 1961 Census of India statistics, Tulu speakers (47.27%) outnumber Kannada speakers (20.62%) in South Canara.[14] The four predominant languages in Tulu Nadu are Tulu, Kannada, Konkani, and Beary.[11][12][13] Hinduism is followed by a large number of the population, with Mogaveeras, Billavas, Ganigas and Bunts forming the largest groups. Kota Brahmins, Shivalli Brahmins, Sthanika Brahmins, Havyaka Brahmins, Goud Saraswat Brahmins (GSBs), Daivajna Brahmins, and Rajapur Saraswat Brahmins also form considerable sections of the Hindu population.[15][16] Christians form a sizable section of Mangalorean society, with Konkani-speaking Catholics, popularly known as Mangalorean Catholics, accounting for the largest Christian community in Tulu Nadu.[16][17] Protestants in Tulu Nadu known as Mangalorean Protestants typically speak Kannada.[18] Most Muslims in Tulu Nadu are Bearys, who speak a dialect called Beary bashe.[19] There is also a sizeable group of landowners following Jainism, that form the Tulu Jain community.[16]

According to the 2001 Government of India Census of the Non-Scheduled Languages of India,[20] Tulu is spoken by 1.72 million people in India. Of this 1.7 million Tulu speakers, approximately 1.5 million live in Karnataka State, approximately 0.12 million (one hundred and twenty thousand) live in Kerala State and approximately 0.1 million (one hundred thousand) live in Maharashtra State. The distribution of the 1.5 million Tulu speakers within Karnataka are not provided in this census. Outside Dakshina Kannada district, many Tulu speakers live in Kodagu, Mysore and Bangalore districts.Reasons

As a result of the States Reorganisation Act (1956), South Canara (part of the Madras Presidency under the British) was incorporated into the dominion of the newly created Mysore State (now called Karnataka).[9] Tulu activists have been demanding a separate Tulu Nadu state since the 1990s. Tulu activists had raised some serious issues on the development of Mangalore and Tulu Nadu. One of them was that the Karnataka State Government has been focussing only on the development of Bangalore, the capital of Karnataka, and its periphery, and cities such as Mangalore and Udupi in Tulu Nadu have received a raw deal. They also alleged that the Government had "totally neglected" Dakshina Kannada and Udupi districts. The Kerala Government too showed similar attitude towards the northern parts of Kasargod district.[1]

The Tulu Rajya Horata Samiti, which is now active in the three districts, advocates Self-rule as the only solution for the much awaited developmental works of the region. The Samithi rejected the initiative of the Karnataka State Government to change the name of Mangalore as Mangaluru. It insisted that if it is changed it should be changed as Kudla. Other demands are renaming Mangalore International Airport as "Tulunadu International Airport". Samiti has a drive to create awareness among the Tulu speaking people with regard to the inevitability of a separate state and enthusing them to fight for the cause."[5]

The Mangalore International Airport terminal. The Tulu Rajya Horata Samiti has recommended that the Mangalore International Airport should be renamed as "Tulunadu International Airport"

In the early 21st century, The Tulu Nadu movement again gained momentum in the region with support from notable Mangalorean poet Kayyara Kinyanna Rai and former Member of Parliament Ramanna Rai. In an interview, Kinyanna Rai said "political boundaries might not mean anything to people who were fighting for the survival of a language and its culture. Karnataka and Kerala governments spoke about "tier II cities" and the "Smart City" concept, but investment was not forthcoming". In an interview, Ramanna Rai said that "the work on the Mangalore-Bangalore railway line was completed after 35 years of its launch." He also said that " he would not accept the laying of a meter gauge line between the two cities and converting it into broad gauge as a development project particularly when there was no rail link for nine years."[1]

In 2008, the former president of the Kannada Sahitya Parishat Harikrishna Punaroor said that "all Tulu organisations from Dakshina Kannada, Udupi and Kasaragod districts will meet shortly to chart out a plan for a separate State and to take it up with the Centre. The people of these districts had a legitimate reason to seek a separate State. Noting that most States came into being on the basis of linguistic consideration. People from Tulu-speaking areas too could stake a claim in this regard. Tulu is one of the five Dravidian languages with its own script. The demand for the inclusion of Tulu in the Eighth Schedule of the Constitution had not materialised over the years due to the apathy of the State and Union governments. Creating a separate State would give a fillip to the growth and sustenance of Tulu. It was the responsibility of elected representatives from the region to press for this cause. If the Government failed to fulfil their demand, an organised agitation would be inevitable."[6]

Mangaloreans are also opposing the Netravati Diversion Project project which intends to divert water from rivers of this region to other parts of upland Karnataka.[21][22] Statewide strikes and agitations called by various Pro Kannada organisations does not invoke any response in Tulu Nadu region.

Mahajan Panel Report

The issue of bifurcation and merger of the northern part of Kasaragod district (to the north of the Chandragiri river) with Karnataka, as recommended by the Justice Mahajan Commission as early as in 1968, was discussed in Lok Sabha elections in 2004. The bifurcation issue re-emerged when the Maharashtra Government put forth its demand to bifurcate and merge Belgaum and the neighbouring areas (now in Karnataka) with Maharashtra. The Vileeneekarana Kriya Samithi (VKS) in Kasargod had then urged Kannadigas to unite and take the issue to the apex court. Though considered a non-issue for the people of Kasaragod in general, the bifurcation scheme was important to the linguistic minorities, Tuluvas, Horanadu Kannadigas, Konkanis, Marathis, Beary, in the district, bordering Karnataka on its north and eastern boundary. The implementation of the Justice Mahajan Commission report that recommended the bifurcation of Kasaragod and merger of its northern part with Karnataka topped the agenda of the "Kasaragod Vileeneekarana Kriya Samithi" (Merger Action Council). The 2,500-member strong "Karnataka Samithi", the "Kannada Sahitya Parishad" and a section of the Horanadu Kannadigas have joined hands with the Vileeneekarana Kriya Samithi. The first official resolution demanding the bifurcation of Kasaragod district was moved and passed in the Kasaragod Municipal Council in 1956, then headed by Ramanna Rai.[23]

According to the veteran Kannada literary and social figure, Kayyar Kinhanna Rai, who is also the founder of the Vileenekarana Kriya Samithi (VKS), the linguistic minorities in the district were not against the Malayalis or Kerala State, per se, but were demanding the implementation of the Justice Mahajan Commission report, vis-a-vis the fulfilment of promises made by the former Chief Ministers, E. M. S. Namboodiripad, C. Achutha Menon and Pattam Thanu Pillai, in this regard.[23]

Noted Mangalorean Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) candidate Balakrishna Shetty had categorically declared his support to the cause. According to Mr. Shetty, he would welcome a move in this regard by the Karnataka Government. In an interview to The Hindu, he said "We are not in power either in Karnataka or in Kerala. It is for the State Government to project the issue and seek the implementation of the Mahajan commission report. Taking into consideration the fact that a majority of the people living in the Northeast areas of the district still follow the Karnataka tradition, culturally and educationally, I would certainly support a bill on bifurcation if moved in Parliament."[23]

United Democratic Front (UDF) candidate N.A. Muhammed in an interview to The Hindu said he would not do anything that would distort or topple a bill favouring the implementation of the Mahajan Commission report. He also that he would not press for implementation of the Mahajan Commission report but would certainly not act against it if such a bill was moved in the Parliament.[23]

Karnataka Samithi leader B.V. Kakkillaya said "A resolution demanding the merger of the north of Kasaragod as recommended by Justice Mahajan was moved and approved by the Vidhan Soudha under the Deve Gowda regime in Karnataka. The S.M. Krishna Government also supported this move. It would be up to the new Karnataka Government to press for the expedition of the resolution at the Centre.[23]

See also

Citations

- ^ a b c d "Tulu Nadu movement gaining momentum". Chennai, India: The Hindu. 2006-08-13. http://www.hindu.com/2006/08/13/stories/2006081317290300.htm. Retrieved 2009-05-27.

- ^ Parpola 2000, p. 386

- ^ Bhat 1998, p. 6

- ^ Economic and political weekly (1997), v. 32, Sameeksha Trust, p. 3114

- ^ a b Tulu Rajya Horata Samithi has urged that the region comprising Tulu speaking people should be given the status of a separate state from Daiji World

- ^ a b Tulu organisations to meet soon from The Hindu

- ^ Samithi seeks separate Tulu state from Deccan Herald

- ^ South Kanara District Gazetteer 1973, p. 36

- ^ a b "States Reorganization Act 1956". Commonwealth Legal Information Institute. http://www.commonlii.org/in/legis/num_act/sra1956250/. Retrieved 2008-07-01.

- ^ History of Tinnevelly by Bishop R. Caldwell, p. 49

- ^ a b C. Vasudevan (1998), Koragas: The Forgotten Lot : the Primitive Tribe of Tulu Nadu : History and Culture , p. 94

- ^ a b The Imperial Gazetteer of India, v. 14, p. 359

- ^ a b The Imperial Gazetteer of India, v. 14, p. 360

- ^ Census of India, District Census Handbook, South Kanara District, p. 192

- ^ Bhat 1998, p. 212

- ^ a b c Bhat 1998, p. 213

- ^ Bhat 1998, p. 214

- ^ South Kanara District Gazetteer 1973, p. 93

- ^ "Beary Sahitya Academy set up". Chennai, India: The Hindu. 2007-10-13. http://www.hindu.com/2007/10/13/stories/2007101361130300.htm. Retrieved 2008-01-15.

- ^ http://censusindia.gov.in/Census_Data_2001/Census_Data_Online/Language/partb.htm

- ^ Opposition to Netravati diversion plan

- ^ Netravati Diversion Project opposed

- ^ a b c d e Demand to implement Mahajan panel report from The Hindu

References

- Bhat, N. Shyam (1998). South Kanara, 1799-1860: a study in colonial administration and regional response. Mittal Publications. ISBN 9788170995869. http://books.google.com/books?id=Z0nZzbFDSAoC&printsec=frontcover. Retrieved 2009-06-07.

- Hunter, William Wilson; James Sutherland Cotton, Richard Burn, William Stevenson Meyer, Great Britain India Office (1909). The Imperial Gazetteer of India. Clarendon Press. http://dsal.uchicago.edu/reference/gazetteer/. Retrieved 2009-01-07.

- Parpola, Marjatta (2000). Kerala Brahmins in transition: a study of a Nampūtiri family. Finnish Oriental Society. ISBN 9789519380483.

- "History" (PDF, 3.7 MB). South Kanara District Gazetteer. Karnataka State Gazetteer. 12. Gazetteer Department (Government of Karnataka). 1973. pp. 33–85. http://gazetteer.kar.nic.in/data/gazetteer/postind/11_1973_2.pdf. Retrieved 2008-10-27.

- "People" (PDF, 2.57 MB). South Kanara District Gazetteer. Karnataka State Gazetteer. 12. Gazetteer Department (Government of Karnataka). 1973. pp. 86–125. http://gazetteer.kar.nic.in/data/gazetteer/postind/11_1973_3.pdf. Retrieved 2008-10-26.

Aspirant states of India Bodoland (Assam) · Bundelkhand (Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh) · Delhi · Gondwana (northern Deccan Plateau) · Gorkhaland (West Bengal) · Harit Pradesh (Uttar Pradesh) · Kamtapur / Greater Cooch Behar (West Bengal) · Karbi Anglong (Assam) · Kodagu (Karnataka) · Kongu Nadu (Tamil Nadu) · Kosal/Koshal (Orissa) · Ladakh (Jammu and Kashmir) · Mahakoshal (Madhya Pradesh) · Mithila (Bihar) · Panun Kashmir (Jammu and Kashmir) · Purvanchal (Uttar Pradesh) · Rayalaseema (Andhra Pradesh) · Telangana (Andhra Pradesh) · Tulu Nadu (Karnataka and Kerala) · Vidarbha (Maharashtra) · Maru Pradesh (Rajasthan) · Vindhya Pradesh (Madhya Pradesh)Categories:- Mangalore

- Regionalism in India

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.