- Disfranchisement after Reconstruction era

-

The Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was ratified in 1870 to protect the suffrage of freedmen after the American Civil War. It prevented any state from denying the right to vote to any male citizen on account of his race.

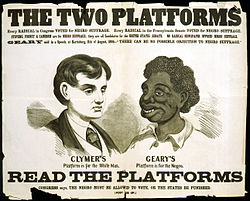

African Americans were an absolute majority of the population in Mississippi, Louisiana and South Carolina, and represented over 40% of the population in four other former Confederate states. Southern conservative whites resisted the freedmen's exercise of political power, fearing black domination. During Reconstruction, blacks controlled a majority of the vote in states such as South Carolina.[1] White supremacist paramilitary organizations allied with the Democratic Party practiced intimidation, violence and assassinations to repress and prevent blacks exercising their civil and voting rights in elections from 1868 through the mid-1870s. In most Southern states, black voting decreased markedly under such pressure, and white Democrats regained political control of Southern legislatures and governors' offices in the 1870s.

In the 1880s, white Southern legislators began devising statutes that created more barriers to voting by blacks and poor whites. Results could be seen in states such as Tennessee. After Reconstruction, Tennessee had the most "consistently competitive political system in the South".[2] A bitter election battle in 1888 marked by unmatched corruption and violence resulted in white Democrats' taking over the state legislature. To consolidate their power, they worked to suppress the black vote and sharply reduced it through changes in voter registration, election procedures and poll taxes.

From 1890 to 1908, starting with Mississippi, Southern Democratic legislators created new constitutions with provisions for voter registration that effectively completed disfranchisement of most African Americans and many poor whites. They created a variety of barriers, including requirements for poll taxes, residency requirements, rule variations, literacy and understanding tests, that achieved power through selective application against minorities, or were particularly hard for the poor to fulfill.[3]

The constitutional provisions survived Supreme Court challenges in cases such as Williams v. Mississippi (1898) and Giles v. Harris (1903). In practice, these provisions, including white primaries, created a maze that blocked most African Americans and many poor whites from voting in Southern states for decades after the turn of the century.[4] Voter registration and turnout dropped sharply across the South. The impact and longevity of disfranchisement can be seen at the feature "Turnout for Presidential and Midterm Elections"[5] at the University of Texas Politics: Historical Barriers to Voting page. It shows results for Texas, the South overall, and the rest of the United States.

Disfranchisement attracted attention of Congress, and some members proposed stripping the South of seats related to the numbers of people who were barred from voting.[6] In the end, Congress did not act to change apportionment. For decades white Southern Democrats exercised Congressional representation derived from a full count of the population, but they disfranchised several million black and white citizens. Southern white Democrats comprised a powerful voting block in Congress until the mid-20th century. Their power allowed them to defeat legislation against lynching, among other issues.[4] Because of the one-party control, many Southern Democrats achieved seniority in Congress and occupied chairmanships of significant Congressional committees, thus increasing their power over legislation, budgets and important patronage projects.

Contents

Reconstruction, KKK, and redemption

Between 1864 and 1866 ten of the eleven Confederate states[7] inaugurated governments that did not provide suffrage and equal civil rights to freedmen. Because of this, Congress refused to readmit these states to the Union and established military districts to oversee affairs until the state governments could be reconstructed.

The Ku Klux Klan (KKK) formed in 1865 and quickly became a powerful secret vigilante group, with chapters across the South, during early Reconstruction. It was one form of insurgency after the Civil War, as armed veterans in the South began varied forms of resistance. The Klan tried to keep black citizens from using their new citizenship and voting power. Starting in 1866, the KKK tried to prevent blacks from voting and from participating in new governments. It carried out lynchings, intimidation, and other attacks against blacks and allied whites, and their property.

The Klan's murders moved the Congress to pass laws to end it. In 1870 the strongly Republican Congress passed an act imposing fines and damages for conspiracy to deprive blacks of the suffrage.[8]

The Force Act of 1870 was used to reduce the power of the KKK. The Federal government banned the use of terror, force or bribery to prevent someone from voting because of his race. It empowered the President to employ the armed forces to suppress organizations which deprived people of rights guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. For such organizations to appear in arms was made rebellion against the United States. The President could suspend habeas corpus in that area.

President Ulysses S. Grant used these provisions in parts of the Carolinas in the fall of 1871. United States marshals supervised state voter registrations and elections, so they could command the help of military or naval forces if needed.[8]

More significant in terms of their effects were paramilitary organizations that arose in the 1870s as part of continuing insurgent resistance in the South. Groups included the White League, formed in Louisiana in 1874 out of white militias, with chapters forming in other Deep South states; the Red Shirts, formed in 1875 in Mississippi but also active in North Carolina and South Carolina; and other "White Liners" such as rifle clubs. Compared to the Klan, they were open societies, better organized, and often solicited newspaper coverage for publicity. Made up of well-armed Confederate veterans, a class that covered most adult men who could have fought in the war, they worked for political aims: to turn Republicans out of office, disrupt their organizing, and use force to intimidate and terrorize freedmen to keep them from the polls. They have been described as "the military arm of the Democratic Party."[9] They were instrumental in many southern states in driving blacks away from the polls and ensuring a white Democratic takeover in most states of legislatures and governorships in the elections of 1876.

State disfranchising constitutions, 1890-1908

See also: Voting rights in the United StatesDespite white Southerners' complaints about Reconstruction, several of the Southern states had kept most provisions of their Reconstruction constitutions for more than two decades, until late in the 19th century.[10] In some states the number of blacks elected to local offices reached a peak in the 1880s. State legislatures passed more restrictions on African Americans. From laws that made election rules and voter registration more complicated, the legislatures moved to new constitutions. Florida passed a new constitution in 1885 that included provisions for poll taxes as a prerequisite for voter registration and voting. From 1890 to 1908, ten of the eleven Southern states rewrote their constitutions. All included provisions that restricted voter registration and suffrage, including new requirements for poll taxes, residency and literacy tests.[11]

With educational improvements, by 1891, the rate of black illiteracy in the South had declined to 58 percent. The white rate of illiteracy in the South was 31 percent.[12] Some states used grandfather clauses to exempt white voters from literacy tests. Other states required black voters to satisfy literacy and understanding administered by white registrars, who subjectively applied criteria, in the process rejecting most black voters. By 1900 the majority of blacks had achieved literacy, but even many of the best-educated "failed" literacy tests administered by white registrars.

The historian J. Morgan Kousser noted, "Within the Democratic party, the chief impetus for restriction came from the black belt members," whom he identified as "always socioeconomically privileged." In addition to wanting to affirm white supremacy, the planter and business elite were also concerned about voting by lower-class and uneducated whites. "They disfranchised these whites as willingly as they deprived blacks of the vote."[13] While other historians have found more complexity in the support of disfranchisement, competition between white elites and lower classes, and the attempt to prevent alliances between lower class whites and African Americans, have both formed part of the motivation for voter restrictions.[11]

With passage of new constitutions, Southern states adopted provisions that caused disfranchisement of large portions of their populations by skirting US constitutional protections of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments. While their voter registration requirements applied to all citizens, in practice they disfranchised most blacks and also "would remove [from voter registration rolls] the less educated, less organized, more impoverished whites as well - and that would ensure one-party Democratic rules through most of the 20th century in the South."[4][14]

There were several negative effects of Reconstruction. For the Republican Party Reconstruction rubbed salt into the wounds of Southern whites, exacerbating their animosity and driving them to the Democrats for virtually a hundred years.[15] For the Democrats, Reconstruction gave them a Southern anchor which was useful for congressional clout but which inhibited the party from fulfilling the role of center-left initiatives prior to President Franklin D. Roosevelt.[16] For the states of the former Confederacy, Reconstruction left behind a one-party Democratic voting pattern which interfered with political competitiveness and with willingness of Republican presidents (and Republicans in Congress as well) to take a positive view of the region. For African Americans, the end of Reconstruction led to disaster, as the reaction epitomized by Jim Crow laws eroded the progress in civil rights and the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution were significantly undone by court decisions such as Plessy v. Ferguson.

Black and white disfranchisement

Poll taxes

In Florida, Alabama, Tennessee, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Georgia, North and South Carolina, and in some northern and western states, proof of having paid taxes or poll taxes was made a prerequisite to voting. The poll tax was sometimes used alone or together with a literacy qualification. Virginia used this policy until 1882 and resumed it again in 1902. Texas added a requirement for a poll tax by state law in 1901.[17] Such taxes excluded poor whites as well at the turn of the century. Many states required payment of the poll tax at a time separate from the election, and then required voters to bring receipts with them to the polls. If they could not locate such receipts, they could not vote. Many states surrounded registration and voting with complex record-keeping requirements.[8] These were particularly difficult for sharecropper and tenant farmers to comply with, as they moved frequently.

Educational and character requirements

Alabama, Arkansas, Mississippi, Tennessee, and South Carolina established an educational requirement, with review by a local registrar of a voter's qualifications. In 1898 Georgia rejected such a device.

Alabama delegates at first hesitated, concerned should illiterate whites lose their votes. But under the stipulation that the new constitution would not disfranchise any white voters and also that it would be submitted to the people for ratification, Alabama was able to pass an educational requirement. It was ratified at the polls November 1901. Its distinctive feature was the "good character clause" (also known as the "grandfather clause"). An appointment board in each county could register "all voters under the present [previous] law" who were veterans or the lawful descendants of such, and "all who are of good character and understand the duties and obligations of citizenship." This gave the board authority essentially to approve voters on a case-by-case basis. They acted to enfranchise whites over blacks.[8]

South Carolina, Louisiana, and later, Virginia incorporated educational requirements as part of their new constitutions. In 1902 Virginia adopted a constitution with the "understanding" clause as a literacy requirement to use until 1904. After that date, Virginia used a poll tax to control suffrage. In addition, application for registration had to be in the applicant's handwriting and written in the presence of the registrar. Thus, someone who could not write, could not vote.[8]

Eight box law

By 1882, the Democrats in South Carolina were firmly in power. Republicans were contained in the heavily black counties of Beaufort and Georgetown. Because the state had a large black majority, white Democrats still feared a possible resurgence of black voters at the polls.

To remove the black threat, the General Assembly created an indirect literacy test, called the "Eight Box Law". The law stipulated that there must be separate boxes for each office, and that the voter had to insert the ballot into the corresponding box or it would not count. The ballots could not have party symbols on them. They had to be of a correct size and type of paper. Many ballots were arbitrarily thrown out because they slightly deviated from the proposed requirements. Ballots would also randomly be thrown out if there were more ballots in a box than registered voters.[18]

The multiple ballot box requirements were challenged in court. On May 8, 1895, Judge Goff of the United States Circuit Court declared the provision unconstitutional and enjoined the state from taking further action under it. But in June 1895 the US Circuit Court of Appeals reversed Judge Goff and dissolved the injunction, leaving the way open for a convention.

The convention met on September 10 and adjourned on December 4, 1895. By the new constitution, South Carolina adopted the Mississippi Plan until January 1, 1898. Any male citizen could be registered who was able to read a section of the constitution or to satisfy the election officer that he understood it when read to him. Those thus registered were to remain voters for life.

After passage of its new constitution, South Carolina white legislators were encouraged by the drop in black voters: by 1896, in a state where African Americans comprised a majority of the population, only 5,500 black voters had succeeded in registering.[19]

Grandfather Clause

The grandfather clause was a provision that allowed a man to vote if his grandfather or father voted on January First, 1867. Because no African American in the South could have voted then, this denied nearly all of the freedmen their right to vote.

Louisiana

With a population evenly divided between races, in 1896 there were 130,334 black voters on the registration rolls and about the same number of whites.[19] State legislators created the constitution of 1898 that enacted the "grandfather" clause. The would-be voter must be able to read and write English or his native tongue, or own property assessed at $300 or more. The test for literacy would be made by the voting registrar. Any citizen who was a voter on January 1, 1867, or his son or grandson, or any person naturalized prior to January 1, 1898, if applying for registration before September 1, 1898, might vote, notwithstanding illiteracy or poverty. Separate registration lists were kept for whites and blacks. The constitution of 1898 required a longer term of residence in the state, county, parish, and precinct before voting than did the constitution of 1879.

The result was predictably devastating to African American voters and by 1900 black voters were reduced to 5,320 on the rolls. By 1910, only 730 blacks were registered, less than 0.5 percent of eligible black men. "In 27 of the state's 60 parishes, not a single black voter was registered any longer; in 9 more parishes, only one black voter was."[19]

North Carolina

In 1894, a coalition of Republicans and Populist Party took control of the North Carolina state legislature (and with it, the ability to elect two US Senators) and elected several US Representatives through electoral fusion.[20] The 1896 election saw even more impressive gains for the fusion coalition; their legislative majority expanded, Republican Daniel Lindsay Russell won the gubernatorial race, and after the election over 1000 elected or appointed black officials, including US Congressman George H. White, served the state. In response to this loss of power, the Democrats decided to run on White Supremacy and disfranchisement in the 1898 in an attempt to scare white voters away from the Republican/Populist coalition. After a bitter race-baiting campaign led by future US Senator Furnifold McLendel Simmons and The Raleigh News & Observer's editor and publisher Josephus Daniels, the North Carolina Democrats won the 1898 election and the following 1900 election, and used their power to disfranchise blacks and ensure that Democratic party and white power would not be threatened again.[2][20][21]

After passing laws restricting voter registration, state Democrats adopted a constitutional suffrage amendment in 1900. It lengthened the term of residence before registration and enacted both an educational qualification (to be assessed by a registrar, which meant that it could be subjectively applied) and prepayment of poll tax. It exempted from the poll tax only those entitled to vote as of January 1, 1867.

The cumulative effect meant that black voters in North Carolina were completely eliminated from voter rolls during the period from 1896-1904. The growth of their thriving middle class was slowed. In North Carolina and other Southern states, there were also the insidious effects of invisibility: "[W]ithin a decade of disfranchisement, the white supremacy campaign had erased the image of the black middle class from the minds of white North Carolinians."[22]

Virginia

In Virginia, disfranchisement was also in response to a coalition of white and black Republicans with populist Democrats, though in Virginia the coalition was formalized as the Readjuster Party. The Readjuster Party held control from 1881 to 1883, electing a governor and controlling the legislature and thereby electing a US Senator. As in North Carolina, state Democrats were able to divide Readjuster supporters through appeals to White Supremacy, and after regaining power changed state laws to disfranchise blacks and ensure that their power would not be threatened. An 80-year stretch of Democratic control would only end in the late 1960s with the collapse of the Byrd Organization machine.

White Primary

About the turn of the century, the Democratic Party in some southern states began to treat its operations as a "private club" and insist on white primaries, barring black and other minority voters who managed to get through other barriers. These became common for all elections, and as the Democratic Party was dominant, barring voters from the primaries meant they could not vote in the only competitive contest. After court challenges overturned party decisions to use the white primary, many states passed laws authorizing the Democratic Party to use the white primary. Texas, for instance, passed such a state law in 1923. It was used to bar Mexican Americans as well as African Americans.[23]

Laws or Constitutions Permitting "White Primaries" in former Confederacy in 1900

No. of African Americans[24] % of Population[24] Year of law or constitution[25] Alabama 827,545 45.26 1901 Arkansas 366,984 27.98 1891 Florida 231,209 43.74 1885–1889 Georgia 1,035,037 46.70 1908 Louisiana 652,013 47.19 1898 Mississippi 910,060 58.66 1890 North Carolina 630,207 33.28 1900 South Carolina 782,509 58.38 1895 Tennessee 480,430 23.77 1889 laws Texas 622,041 20.40 1901 / 1923 laws Virginia 661,329 35.69 1902 Total 7,199,364[26] 37.94[26] — Congressional response

The North had heard the South's version of Reconstruction abuses, such as financial corruption, high taxes and incompetent freedmen. Industry wanted to invest in the South and not worry about political problems. The early 1900s were a peak of reconciliation between white veterans of the North and South armies. As historian David Blight demonstrated in Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory, reconciliation meant the pushing aside by whites of the major issues of race and suffrage. The Southern whites were effective for many years at having their version of history accepted, especially as it was confirmed in ensuing decades by influential historians of the Dunning School at Columbia University and other institutions.

Disfranchisement of African Americans in the South was covered by national newspapers and magazines as new constitutions were created, and many Northerners were outraged and alarmed. In 1900 as the Committee of Census of Congress considered proposals for adding more seats to the House of Representatives because of increased population, Edgar D. Crumpacker (R-IN) proposed stripping Southern states of seats to reflect the numbers of people they had disfranchised. The Committee and House failed to agree on this proposal.[6] Supporters of black suffrage worked to secure Congressional investigation of disfranchisement, but the concerted opposition of the Southern Democratic block was aroused, and the efforts failed.[8]

From 1896-1900, the House of Representatives had acted in over 30 cases to set aside election results from Southern states where the House Elections Committee had concluded that "black voters had been excluded due to fraud, violence, or intimidation." In the late 1890s, however, it began to back off from its enforcement of the Fifteenth Amendment and suggested that state and Federal courts should exercise oversight of this issue.[27]

In 1904 Congress administered a coup de grâce to efforts to investigate disfranchisement in its decision in the 1904 South Carolina election challenge of Dantzler v. Lever. Despite its earlier actions in overturning flawed state elections, the House Committee on Elections upheld Lever's victory. Further, it suggested that citizens of South Carolina who felt their rights were denied should appropriately take their cases to the state courts, and ultimately, the Supreme Court.[28]

Despite that decision, in later sessions, members continued to raise the issue of disfranchisement and apportionment. On December 6, 1920, Representative George H. Tinkham from Massachusetts offered a resolution for the Committee of Census to investigate alleged disfranchisement of blacks. His intention was to enforce the provisions of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments. In addition, he believed there should be reapportionment in the House related to the voting population of southern states, rather than the general population as enumerated in the census. Tinkham detailed how outsized the South's representation was related to its total voters:

- States with 10 representatives:

- Alabama, with total vote of 62,345.

- Minnesota, with total vote of 299,127.

- Iowa, with total vote of 316,377.

- California, with 11 representatives, had a total vote of 644,790.

- States with 12 representatives:

- Georgia, with vote of 59,196.

- New Jersey, with vote of 338,461.

- Indiana, with 13 seats and total vote of 565,216.

- States with 8 representatives:

- Louisiana, with total vote of 44,794.

- Kansas, with vote of 425,641.

- States with four representatives:

- Florida, with total vote of 31,613.

- Colorado, with vote of 208,855.

- Maine, with vote of 121,836.

- States with six or seven representatives:

- South Carolina, 7, with total vote of 25,433.

- Nebraska, 6, with vote of 216,014.

- West Virginia, 6, with vote of 211,643.

20th century Supreme Court decisions

African Americans and their allies worked hard to regain their ability to exercise rights of citizens. Booker T. Washington, better known for what some called an accommodationist approach at Tuskegee Institute, called on northern backers to help finance legal challenges to disfranchisement and segregation. He thus helped raise funds and also arranged for representation on some cases, such as the two for Giles in Alabama.[30]

In its ruling in Giles v. Harris (1903), the United States Supreme Court under Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., effectively upheld such voter registration provisions in dealing with a challenge to the Alabama constitution. Its decision said the provisions were not targeted at African Americans and thus did not deprive them of rights. This has been characterized as the "most momentous ignored decision" in constitutional history.[31]

Trying to deal with the grounds of the Court's ruling, Giles mounted another challenge. In Giles v. Teasley (1904), the U.S. Supreme Court again upheld the disfranchising constitution. That same year the Congress refused to overturn a disputed election, and essentially sent plaintiffs back to the courts. It was not until later in the 20th century that such legal challenges on disfranchisement began to meet some success in the courts.

With the founding of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909, the interracial group based in New York began to provide financial and strategic support to lawsuits on voting issues. What became the NAACP Legal Defense Fund organized and mounted numerous cases in repeated court and legal challenges to the many barriers of segregation, including disfranchisement provisions of the states. The NAACP often represented plaintiffs directly, or helped raise funds to support legal challenges. The NAACP also worked at public education, lobbying of Congress, demonstrations, and encouragement of theater and academic writing. NAACP chapters arose in cities across the country and membership increased rapidly in the South.

Successful challenges

In Guinn v. United States (1915), the Supreme Court invalidated the Oklahoma Constitution's "old soldier" and "grandfather" exemptions from literacy tests, which in practice had resulted in blacks being denied registration to vote, as had occurred in numerous Southern states. This decision affected similar provisions in the constitutions of Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, North Carolina, and Virginia election rules. Oklahoma and other states quickly reacted by passing laws creating other rules for voter registration that worked against blacks and minorities.[32] This was the first of many cases in which the NAACP filed a brief.

In Lane v. Wilson (1939), the Supreme Court again invalidated an Oklahoma provision designed to disfranchise blacks, the one adopted to replace the clause struck down in Guinn. This clause permanently disfranchised everyone qualified to vote who had not registered to vote in a twelve day window between April 30 and May 11, 1916, except for those who voted in 1914. While designed to be more resistant to facial challenges, as the law did not specifically mention race, it was struck down nonetheless, partially because it relied on the 1914 election which itself was held under the rule invalidated in Guinn.[33]

In Smith v. Allwright (1944), the Supreme Court reviewed a Texas case and ruled against the white-only primaries prevalent in the South. In major cities, civil rights organizations moved quickly to register black voters. For instance, in Georgia, in 1940 only 20,000 blacks had managed to register to vote. After the Supreme Court decision, the All-Citizens Registration Committee (ACRC) of Atlanta started organizing. By 1947 they and others had succeeded in getting 125,000 African Americans registered, 18.8% of those of eligible age.[34]

Each legal victory was followed by renewed efforts to control black voting through different schemes. In 1958 Georgia passed a new registration act that required those who were illiterate to satisfy understanding tests by correctly answering 20 of 30 questions related to citizenship posed by the voting registrar. Despite advances by many blacks in education, since the voting registrar was the judge of whether the prospective voter answered correctly, the results in practice were a suppression of black voting. In Terrell County, for instance, which was 64% black, after passage of the act, in 1958 only 48 African Americans managed to register to vote.[35]

Civil Rights Movement

See also: African-American Civil Rights MovementThe NAACP's steady progress on individual cases was thwarted by southern states' continuing resistance and passage of new statutory barriers to expansion of the franchise. Through the 1950s and 1960s, private citizens enlarged the effort by becoming activists throughout the South, led by many African-American churches and their leaders, and joined by young and older activists from northern states. Nonviolent confrontation and demonstrations were mounted in numerous Southern cities, often provoking violent reaction by white bystanders and authorities. The moral crusade of the Civil Rights Movement gained national media coverage, attention across the country, and a growing national outcry for change. Violence and murders in Alabama in 1963 and Mississippi in 1964 gained support for the activists' cause at the national level. President John F. Kennedy introduced civil rights legislation before he was assassinated.

President Lyndon B. Johnson took up the charge. In January 1964, President Lyndon Johnson met with civil rights leaders. On January 8, during his first State of the Union address, Johnson asked Congress to "let this session of Congress be known as the session which did more for civil rights than the last hundred sessions combined." On January 23, 1964, the 24th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, prohibiting the use of poll taxes in national elections, was ratified with the approval of South Dakota, the 38th state to do so.

On June 21, civil rights workers Michael Schwerner, Andrew Goodman, and James Chaney, disappeared in Neshoba County, Mississippi. The three were volunteers aiding in the registration of black voters as part of the Mississippi Freedom Summer Project. Forty-four days later the Federal Bureau of Investigation recovered their bodies from an earthen dam where they were buried. The Neshoba County deputy sheriff Cecil Price and 16 others, all Klan members, were indicted for the murders; seven were convicted.

On July 2, President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964.[36] This Act prohibited segregation in public places and barred unequal application of voter registration requirements. It did not abolish literacy tests, however, and these had been used to disqualify African Americans and poor white voters.

As the United States Department of Justice stated, "By 1965 concerted efforts to break the grip of state disfranchisement had been under way for some time, but had achieved only modest success overall and in some areas had proved almost entirely ineffectual. The murder of voting-rights activists in Philadelphia, Mississippi, gained national attention, along with numerous other acts of violence and terrorism. Finally, the unprovoked attack on March 7, 1965, by state troopers on peaceful marchers crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, en route to the state capitol in Montgomery, persuaded the President and Congress to overcome Southern legislators' resistance to effective voting rights legislation. President Johnson issued a call for a strong voting rights law and hearings began soon thereafter on the bill that would become the Voting Rights Act."[37] This outlawed the requirement that would-be voters in the United States take literacy tests to qualify to register to vote. It also provided for recourse for local voters to Federal intervention and oversight, and monitoring of areas that had had historically low voter turnouts.

See also

- Electoral fraud

- Jim Crow laws

- Nadir of American race relations

- Race legislation in the United States

- Voting rights in the United States

References

- ^ Gabriel J. Chin & Randy Wagner, "The Tyranny of the Minority: Jim Crow and the Counter-Majoritarian Difficulty,"43 Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review 65 (2008)

- ^ a b J. Morgan Kousser, The Shaping of Southern Politics: Suffrage Restriction and the Establishment of the One-Party South, 1880-1910, p.104

- ^ Richard H. Pildes, "Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon", Constitutional Commentary, Vol.17, 2000, pp.12-13 Accessed 10 Mar 2008

- ^ a b c Richard H. Pildes, "Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon", Constitutional Commentary, Vol.17, 2000, p.10 Accessed 10 Mar 2008

- ^ http://cake.la.utexas.edu//txp_media/html/vce/features/0503_02/slide2.html

- ^ a b COMMITTEE AT ODDS ON REAPPORTIONMENT, The New York Times, 20 Dec 1900, accessed 10 Mar 2008

- ^ Tennessee voluntarily ratified the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution and thus averted Reconstruction in the form of military occupation.

- ^ a b c d e f Andrews, E. Benjamin (1912). History of the United States. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- ^ George C. Rable, But There Was No Peace: The Role of Violence in the Politics of Reconstruction, Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1984, p. 132

- ^ W.E.B. DuBois, Black Reconstruction in America, 1868-1880, New York: Oxford University Press, 1935; reprint, New York: The Free Press, 1998

- ^ a b Michael Perman.Struggle for Mastery: Disfranchisement in the South, 1888-1908. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001, Introduction

- ^ 1878-1895: Disfranchisement, Southern Education Foundation, accessed 16 Mar 2008

- ^ J. Morgan Kousser.The Shaping of Southern Politics: Suffrage Restriction and the Establishment of the One-Party South, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1974

- ^ Glenn Feldman, The Disfranchisement Myth: Poor Whites and Suffrage Restriction in Alabama, Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2004, pp. 135–136

- ^ See Solid South.

- ^ Woodrow Wilson, e.g., one of the two Democrats to occupy the White House between Lincoln and FDR, directed the re-segregation of federal facilities in the District of Columbia after they had been de-segregated by Republican administrations.

- ^ Texas Politics: Historical Barriers to Voting, accessed 11 Apr 2008 Archived April 2, 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Holt, Thomas (1979). Black over White: Negro Political Leadership in South Carolina during Reconstruction. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- ^ a b c Richard H. Pildes, "Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon", 2000, p.12 Accessed 10 Mar 2008

- ^ a b North Carolina History Project "Fusion Politics"

- ^ The North Carolina Collection, UNC Libraries "The North Carolina Election of 1898"

- ^ Richard H. Pildes, "Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon", 2000, p.12 and 27 Accessed 10 Mar 2008

- ^ Texas Politics: Historical Barriers to Voting, accessed 11 Apr 2008 Archived April 2, 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Historical Census Browser, 1900 Federal Census, University of Virginia, accessed 15 Mar 2008

- ^ Julien C. Monnet, "The Latest Phase of Negro Disfranchisement", Harvard Law Review, Vol.26, No.1, Nov. 1912, p.42, accessed 14 Apr 2008

- ^ a b Data obtained from existing data in table. Number of African Americans total obtained by 827,545+366,984+231,209+...+661,329=7,199,364. Percentage data: 827,545/45.26%=1,828,425(rounded to nearest whole) for total population of Alabama, 366,984/27.98%=1,311,594(nearest whole) for Arkansas, etc. Total of all state populations=18,975,448. 7,199,364/18,975,448=37.94%

- ^ Richard H. Pildes, "Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon", Constitutional Commentary, Vol. 17, 2000, p.19-20 Accessed 10 Mar 2008

- ^ Richard H. Pildes, "Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon", Constitutional Commentary, Vol. 17, 2000, p.20-21 Accessed 10 Mar 2008

- ^ "Demands Inquiry on Disfranchising: Representative Tinkham Aims to Enforce 14th and 15th Articles of the Constitution", The New York Times, 5 Dec 1920, accessed 18 Mar 2008[dead link]

- ^ Richard H. Pildes, "Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon", Constitutional Commentary, Vol. 17, 2000, p. 21 Accessed 10 Mar 2008

- ^ Richard H. Pildes, "Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon", Constitutional Commentary, Vol. 17, 2000, p.32 Accessed 10 Mar 2008

- ^ Richard M. Valelly, The Two Reconstructions: The Struggle for Black Enfranchisement, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004, p.141

- ^ http://supreme.justia.com/us/307/268/case.html

- ^ Chandler Davidson and Bernard Grofman, Quiet Revolution in the South: The Impact of the Voting Rights Act, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994, p.70

- ^ Chandler Davidson and Bernard Grofman, Quiet Revolution in the South: The Impact of the Voting Rights Act, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994, p.71

- ^ "Civil Rights during the administration of Lyndon B. Johnson". LBJ Library and Museum. http://www.lbjlib.utexas.edu/johnson/lbjforkids/civil_timeline.shtm. Retrieved 2007-02-25.

- ^ "Introduction To Federal Voting Rights Laws". United States Department of Justice. http://www.usdoj.gov/crt/voting/intro/intro_b.htm. Retrieved 2007-02-25.

Categories:- African American history

- Elections in the United States

- Electoral restrictions

- History of African-American civil rights

- History of racial segregation in the United States

- History of voting rights in the United States

- History of the Southern United States

- Taxation in the United States

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.