- Mehmed II

-

"Fatih Sultan Mehmet" redirects here. For the bridge that spans the Bosphorus strait, see Fatih Sultan Mehmet Bridge.

Mehmed II

Mehmed IIOttoman Sultan

Miniature of Mehmed II Reign 1444–46 Reign 2 1451–81 Period Rise of the Ottoman Empire Full Name Fatih Sultan Mehmet Ottoman Turkish محمد ثانى Born March 30, 1432 Birthplace Edirne Died May 3, 1481 (aged 49) Place of death Hünkârçayırı, near Gebze Predecessor Murad II Successor Murad II Predecessor 2 Murad II Successor 2 Bayezid II Royal House House of Osman Dynasty Ottoman Dynasty Valide Sultan Hüma Hatun Mehmed II (March 30, 1432 – May 3, 1481) (Arabic: محمد الفاتح) (Persian: محمد دوم) (Ottoman Turkish: محمد ثانى Meḥmed-i s̠ānī, Turkish: II. Mehmet), (also known as el-Fātiḥ (الفاتح), "the Conqueror" in Ottoman Turkish, or, in modern Turkish, Fatih Sultan Mehmet; also called Mahomet II[1][2] in early modern Europe) was Sultan of the Ottoman Empire (Rûm until the conquest) for a short time from 1444 to September 1446, and later from February 1451 to 1481. At the age of 21, he conquered Constantinople and brought an end to the Byzantine Empire, absorbing its administrative apparatus into the Ottoman state. Mehmet continued his conquests in Asia, with the Anatolian reunification, and in Europe, as far as Belgrade. Mehmed II is regarded as a national hero in Turkey, and his name is given to Istanbul's Fatih Sultan Mehmet Bridge.

Contents

Early reign

Mehmed II was born on March 30, 1432, in Edirne, then the capital city of the Ottoman state. His father was Sultan Murad II (1404–51) and his mother Valide Sultan Hüma Hatun, born in Devrekani county of Kastamonu province, was a daughter of Abdullah of Hum.

When Mehmed II was eleven years old he was sent to Amasya to govern and thus gain experience, as per the custom of Ottoman rulers before his time. After Murad II made peace with the Karaman Emirate in Anatolia in August 1444, he abdicated the throne to his 12-year-old son Mehmed II. Sultan Murad II had sent him a number of teachers for him to study under.[3]

This Islamic education had a great impact in molding the mindset of Mehmed and reinforcing his Muslim beliefs. He began to praise and promote the application of Sharia law. He was influenced in his practice of Islamic epistemology by contemporaneous practitioners of science - particularly by his mentor, Molla Gürani - and he followed their approach. The influence of Ak Şemseddin in Mehmed's life became predominant from a young age, especially in the imperative of fulfilling his Islamic duty to overthrow the Byzantine empire by conquering Constantinople.[4]

In his first reign, he defeated the crusade led by János Hunyadi after the Hungarian incursions into his country broke the conditions of the truce Peace of Szeged. Cardinal Julian Cesarini, the representative of the pope, had convinced the king of Hungary that breaking the truce with Muslims was not a betrayal.[5] At this time Mehmed II asked his father Murad II to reclaim the throne, but Murad II refused. Angry at his father, who had long since retired to a contemplative life in southwestern Anatolia, Mehmed II wrote: "If you are the Sultan, come and lead your armies. If I am the Sultan I hereby order you to come and lead my armies." It was only after receiving this letter that Murad II led the Ottoman army and won the Battle of Varna in 1444.

It is said Murad II's return to the throne was forced by Çandarlı Halil Paşa, the grand vizier at the time, who was not fond of Mehmed II's rule, because Mehmed II's influential teacher had a rivalry with Çandarlı. Çandarlı was later executed by Mehmed II during the siege of Constantinople on the grounds that he had been bribed by or had somehow helped the defenders.

During his early reign, he married a Christian Albanian, Valide Sultan Emine Gülbahar, the step-mother of his successor and son Bayezid II whose biological mother was Mükrime Hatun.[6][7]

Conquest of Constantinople

When Mehmed II ascended the throne in 1451 he devoted himself to strengthening the Ottoman Navy, and in the same year made preparations for the taking of Constantinople. In the narrow Bosporus Straits, the fortress Anadoluhisarı had been built by his great-grandfather Bayezid I on the Asiatic side; Mehmed erected an even stronger fortress called Rumelihisarı on the European side, and thus having complete control of the strait. Having completed his fortresses, Mehmet proceeded to levy a toll on ships passing within reach of their cannon. A Venetian vessel refusing signals to stop, was sunk with a single shot and all the surviving sailors beheaded.[8]

MEHMED THE CONQUEROR ( Fatih Sultan Mehmed Khan Ghazi ) Left and Right: Portraits of MEHMED THE CONQUEROR

Two at Center: The Conquest of Constantinople on 29 May 1453

Ottoman miniature depicting Fatih Sultan Mehmed Khan smelling a rose Entry of Fatih Sultan Mehmed into Constantinople by Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant. Fatih Sultan Mehmed Khan

Fall of Constantinople by

Fausto Zonaro (1854-1929).Fatih Sultan Mehmed Khan

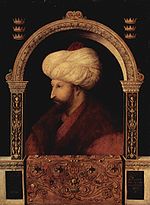

Portrait by Gentile Bellini, 1479

(70 x 52 National Gallery, London).In 1453 Mehmed commenced the siege of Constantinople with an army between 80,000 to 200,000 troops and a navy of 320 vessels, though the bulk of them were transports and storeships. The city was now surrounded by sea and land; the fleet at the entrance of the Bosphorus was stretched from shore to shore in the form of a crescent, to intercept or repel any assistance from the sea for the besieged.[8]

In early April, the Siege of Constantinople began. After several failed assaults, the city's walls held off the Turks with great difficulty, even with the use of the new Orban's bombard, a cannon similar to the Dardanelles Gun. The harbor of the Golden Horn was blocked by a boom chain and defended by twenty-eight warships.

On April 22, Mehmed transported his lighter warships overland, around the Genoese colony of Galata and into the Golden Horn's northern shore; eighty galleys were transported from the Bosphorus after paving a little over one-mile route with wood. Thus the Byzantines stretched their troops over a longer portion of the walls. A little over a month later, Constantinople fell on May 29 following a fifty-seven day siege.[8] After this conquest, Mehmed moved the Ottoman capital from Adrianople to Constantinople. On his accession as conqueror of Constantinople, aged 21, Mehmed was reputed fluent in several languages, including Turkish, Greek, Hebrew, Arabic, Persian, and Latin.[9][10]

Reference is made to the prospective conquest of Constantinople in an authentic hadith, attributed to a saying of the Prophet Muhammad. "Verily you shall conquer Constantinople. What a wonderful leader will he be, and what a wonderful army will that army be!"[11] Ten years after the conquest of Constantinople Mehmed II visited the site of Troy and boasted that he had avenged the Trojans by having conquered the Greeks (Byzantines).[12]

When Mehmed stepped into the ruins of the Boukoleon, known to the Ottomans and Persians as the Palace of the Caesars, probably built over a thousand years before by Theodosius II, he uttered the famous lines of Persian poetry:[citation needed]

- The spider weaves the curtains in the palace of the Caesars;

- the owl calls the watches in the towers of Afrasiab.

After the Fall of Constantinople, Mehmed claimed the title of "Caesar" of Rome (Kayser-i Rûm), although this claim was not recognized by the Patriarch of Constantinople, or Christian Europe. Mehmed's claim rested with the concept that Constantinople was the seat of the Roman Empire, after the transfer of its capital to Constantinople in 330 AD and the fall of the Western Roman Empire. Mehmed also had a blood lineage to the Byzantine Imperial family; his predecessor, Sultan Orhan I had married a Byzantine princess, and Mehmed may have claimed descent from John Tzelepes Komnenos.[9] He was not the only ruler to claim such a title, as there was the Holy Roman Empire in Western Europe, whose emperor, Frederick III, traced his titular lineage from Charlemagne who obtained the title of Roman Emperor when he was crowned by Pope Leo III in 800 - although never recognized as such by the Byzantine Empire.

The Byzantine historian Doukas,[13] stated that after the conquest of Constantinople, Mehmed II ordered the 14-year old son of the Grand Duke Lucas Notaras brought to him "for his pleasure". When the father refused to deliver his son to such a fate he had them both decapitated on the spot.[14] Another contemporary Greek source, Leonard of Chios, professor of theology and Archbishop of Mytilene, tells the same story in his letter to Pope Nicholas. He describes Mehmed II requesting for the 14 year old handsome youth to be brought "for his pleasure".[15] This story was originally recorded by Doukas, a Byzantine Greek living in Constantinople at the time of the fall of the city, and does not appear in accounts by other Greeks who witnessed the conquest.[16] Some modern scholars believe that this tale is merely one of a long series of attempts to portray Muslims as morally inferior, and point to the story of Saint Pelagius as its probable inspiration.[16]

Conquests in Asia

The Fatih Mosque built by order of Sultan Mehmed II in Constantinople, was the first imperial Ottoman mosque built in the city after the Ottoman conquest

The Fatih Mosque built by order of Sultan Mehmed II in Constantinople, was the first imperial Ottoman mosque built in the city after the Ottoman conquest

The conquest of Constantinople allowed Mehmed II to turn his attention to Anatolia. Mehmed II tried to create a single political entity in Anatolia by capturing Turkish states called Beyliks and the Greek Empire of Trebizond in northeastern Anatolia and allied himself with the Crimean Khanate in the Crimea. Uniting the Anatolian Beyliks was first accomplished by Sultan Bayezid I, more than fifty years earlier than Mehmed II but after the destructive Battle of Ankara back in 1402, the newly formed Anatolian unification was gone. Mehmed II recovered the Ottoman power on other Turkish states. These conquests allowed him to push further into Europe.

Another important political entity which shaped the Eastern policy of Mehmed II was the White Sheep Turcomans. With the leadership of Uzun Hasan, this Turcoman kingdom gained power in the East but because of their strong relations with the Christian powers like Empire of Trebizond and the Republic of Venice and the alliance between Turcomans and Karamanid tribe, Mehmed saw them as a threat to his own power. He led a successful campaign against Uzun Hasan in 1473 which resulted with the decisive victory of the Ottoman Empire in the Battle of Otlukbeli.

Conquests in Europe

After the Fall of Constantinople, Mehmed would also go on to conquer the Despotate of Morea in the Peloponnese in 1460, and the Empire of Trebizond in northeastern Anatolia in 1461. The last two vestiges of Byzantine rule were thus absorbed by the Ottoman Empire. The conquest of Constantinople bestowed immense glory and prestige on the country.

Mehmed II advanced toward Eastern Europe as far as Belgrade, and attempted to conquer the city from John Hunyadi at the Siege of Belgrade in 1456. Hungarian commanders successfully defended the city and Ottomans retreated with heavy losses but at the end, Ottomans occupied nearly all of Serbia.

In 1463, after a dispute over the tribute paid annually by the Bosnian kingdom, Mehmed invaded Bosnia and conquered it very quickly, executing the last Bosnian king Stephen Tomašević and his uncle Radivoj.

In 1462 Mehmed II came into conflict with Prince Vlad III Dracula of Wallachia. Vlad III, who had spent part of his childhood alongside Mehmed,[17] ambushed several Ottoman forces, inflicting heavy casualties and viciously executing the survivors. Vlad III announced that he had impaled over 23,000 Turks, at which point Mehmed II decided to abandon his siege of Corinth and lead the attack against Dracula himself.[18] This nearly proved fatal, when Vlad III counterattacked the much larger Ottoman army in 1462 during the Night Attack. Vlad III led a small force directly into Mehmed's camp as they slept, causing many casualties and attempting to personally assassinate Mehmed II.[19] Forced to retreat from Wallachia due to Vlad's scorched earth policies and demoralizing brutality, Mehmed II left Radu cel Frumos, Vlad's brother, with a small force in order to win over the local boyars, who had been persecuted by Vlad III. Radu eventually managed to take control of Wallachia and was honored the title of Bey in the same year. After several more battles, his brother Vlad lost hold of his power and escaped from his country to Hungary, where he was imprisoned due to forged documents questioning his loyalty.

In 1475, the Ottomans suffered a great defeat at the hands of Stephen the Great of Moldavia at the Battle of Vaslui. In 1476, Mehmed won a pyrrhic victory against Stephen at the Battle of Valea Albă. He besieged the capital of Suceava, but could not take it, nor could he take the Castle of Târgu Neamţ. With a plague running in his camp and food and water being very scarce, Mehmed was forced to retreat.

The Albanian resistance in Albania between 1443 and 1468 led by George Kastrioti Skanderbeg (İskender Bey), an Albanian noble and a former member of the Ottoman ruling elite, prevented the Ottoman expansion into the Italian peninsula. Skanderbeg had united the Albanian Principalities in a fight against the Empire in the League of Lezhë in 1444. Mehmed II couldn't subjugate Albania and Skanderbeg while the latter was alive, even though twice (1466 and 1467) he led the Ottoman armies himself against Krujë. After death of Skanderbeg in 1468, Albanians couldn't find a leader to replace him and Mehmed II eventually conquered Krujë and Albania on 1478.

Mehmed II invaded Italy in 1480. The intent of his invasion was to capture Rome and "reunite the Roman Empire", and, at first, looked like he might be able to do it with the easy capture of Otranto in 1480 but Otranto was retaken by Papal forces in 1481 after the death of Mehmed.

Administrative actions

Mehmed II amalgamated the old Byzantine administration into the Ottoman state.[citation needed] He first introduced the word Politics into Arabic "Siyasah" from a book he published and claimed to be the collection of Politics doctrines of the Byzantine Caesars before him. He gathered Italian artists, humanists and Greek scholars at his court, allowed the Byzantine Church to continue functioning, ordered the patriarch to translate Christian doctrine into Turkish, and called Gentile Bellini from Venice to paint his portrait. Mehmed II also tried to get Muslim scientists and artists to his court in Constantinople, started a University, built mosques e.g. the Fatih Mosque, waterways, and the Topkapı Palace.

Mehmed II's reign is also well known for the religious tolerance with which he treated his subjects, especially among the conquered Christians, which was very unusual for Europe in the Middle Ages. His army recruited from the Devshirme, a group that took first-born Christian subjects at a young age that were destined for the sultans court. The less able, but physically strong were put into the army or the sultan's personal guard, the Janissaries.

Within Constantinople, Mehmed established a millet or an autonomous religious community, and appointed the former Patriarch[who?] as religious governor of the city.[citation needed] His authority extended only to the Orthodox Christians within the city, and this excluded the Genoese and Venetian settlements in the suburbs, and excluded Muslim and Jewish settlers entirely. This method allowed for an indirect rule of the Christian Byzantines and allowed the occupants to feel relatively autonomous even as Mehmed II began the Turkish remodeling of the city, turning it into the Turkish capital, which it remained until the 1920s.

Personal life

Mehmed II had several wives: Validā Khātûn Âminā Kul-Bahar Khātûn, a Christian Albanian, who died in 1492,[6][7] Gevher Khātûn; Gül-Şâh (Kulshah) Khātûn; Mûkrîmā (Sitt-î Mükrime) Khātûn;[20] Çiçek Khātûn; Helenā Khātûn, who died in 1481, daughter of Demetrios Palaiologos and the Despot of Morea; briefly Anna Khātûn, the daughter of the Emperor of Trebizond; and Alexias Khātûn, a Byzantine princess. Another son of his was Djem Zizim, who died in 1495.

Fatih Sultan Mehmet Bridge was named after him that straddles the Bosporus Straits in Istanbul in the twentieth century.

Fatih Sultan Mehmet Bridge was named after him that straddles the Bosporus Straits in Istanbul in the twentieth century.

Death

Mehmed died on May 3, 1481, at the age of forty-nine. Mehmed's primary doctor, "Jacob Pasha" an Italian born convert to Islam was suspected of administering poison to Mehmed over a period of time and was executed.[citation needed]

Another source states that: "The likeliest possibility is that Mehmed was also poisoned by his Persian doctor. Despite numerous Venetian assassination attempts over the years, the finger of suspicion points most strongly at his son, Bayezit."[21]

Mehmed was buried in his Türbe in the cemetery within the Fatih Mosque Complex [22]

Legacy

After the fall of Constantinople, he founded many universities and colleges in the city, some of which are still active. Mehmed II is also recognized as the first Sultan to codify criminal and constitutional law long before Suleiman the Magnificent and he thus established the classical image of the autocratic Ottoman sultan. Mehmed II's tomb is located at Fatih Mosque in Istanbul.

During his thirty-one year rule, he waged several wars expanding the Ottoman Empire. The conquest of Constantinople, and all the Turkish kingdoms and territories of Asia Minor, Bosnia, Kingdom of Serbia, and Albania. He carried out many internal administrative reforms that put his country on the path to prosperity and paved the way for subsequent sultans to focus on expanding the State and the expansion into new territories. he also put the first principles of civil law and the Penal Code, changed corporal punishment, that was completed through Suleiman the Magnificent later.[citation needed]

Mehmed left behind an imposing reputation in both the Islamic and Christian worlds. The Fatih Sultan Mehmet Bridge was named after him that straddles the Bosporus Straits in Istanbul in the twentieth century. His name and picture appears on the paper currency of the Turkish thousand Lira note, which was in circulation between 1986 to 1992.[23]

Mehmed II is the eponymous subject of Rossini's 1820 opera Maometto II.

Mehmed II's portrait was depicted on the reverse of the Turkish 1000 lira banknotes of 1986-1992.[24]

It is notable that Mehmet II is not considered the first ruler of Constantinople of Turkic origin.[25][26] Before him, the Christian Leo IV the Khazar was a de jure Roman Emperor.

Freedom of the Bosnian Franciscans

The Firman given to the Bosnian Franciscans

The Firman given to the Bosnian Franciscans

- Mehmed II's Firman on the freedom of the Bosnian Franciscans

"I, the Sultan Khan the Conqueror,

hereby declare the whole world that,

The Bosnian Franciscans granted with this sultanate firman are under my protection. And I command that:

No one shall disturb or give harm to these people and their churches! They shall live in peace in my state. These people who have become emigrants, shall have security and liberty. They may return to their monasteries which are located in the borders of my state.

No one from my empire notable, viziers, clerks or my maids will break their honour or give any harm to them!

No one shall insult, put in danger or attack these lives, properties, and churches of these people!

Also, what and those these people have brought from their own countries have the same rights...

By declaring this firman, I swear on my sword by the holy name of Allah who has created the ground and sky, Allah's prophet Mohammed, and 124,000 former prophets that; no one from my citizens will react or behave the opposite of this firman!"

This oath firman, which has provided independence and tolerance to the ones who are from another religion, belief, and race was declared by Mehmed II the Conqueror and granted to Angjeo Zvizdovic of the Franciscan monastery in Fojnica, after the conquest of Bosnia and Herzegovina on May 28 of 1463.[27][28] The firman has been recently raised and published by the Ministry of Culture of Turkey for the 700th anniversary of the foundation of the Ottoman State. The edict was issued by the Sultan Mehmed II the Conqueror to protect the basic rights of the Bosnian Christians when he conquered that territory in 1463. The original edict is still kept in the same monastery in Fojnica.

It is one of the oldest documents on religious freedom. Mehmed II's oath was entered into force in the Ottoman Empire on May 28, 1463. In 1971, the United Nations published a translation of the document in all the official U.N. languages.

See also

- General

- Sultan, Byzantine Empire, Ottoman Empire

- Events

- Expansion of the Ottoman Empire, Decline of the Byzantine Empire, Fall of Constantinople, Battle of Varna

- Locations

- Turkey, Fatih Sultan Mehmet Bridge

- Other

- Cem (His younger son)

Further reading

- Babinger, Franz, Mehmed the Conqueror and his Time. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 1978. ISBN 0691 0 1078 1

- Dwight, Harrison Griswold, Constantinople, Old and New. New York: C. Scribner's Sons, 1915

- Hamlin, Cyrus, Among the Turks. New York: R. Carter & Bros, 1878

- Harris, Jonathan, The End of Byzantium. New Haven CT and London: Yale University Press, 2010. ISBN 978 0 30011786 8

- Imber, Colin, The Ottoman Empire. London: Palgrave/Macmillan, 2002. ISBN 0 333 613872

- Philippides, Marios, Emperors, Patriarchs, and Sultans of Constantinople, 1373-1513: An Anonymous Greek Chronicle of the Sixteenth Century. Brookline MA: Hellenic College Press, 1990. ISBN 0917 653 165

- Nehme, Lina Murr, "1453, Mahomet II impose le Schisme Orthodoxe". Lebanon, Aleph & Taw, 2003. ISBN 2-86839-816-2.

References

- General information

- Lord Kinross (1977). The Ottoman Centuries: The Rise And Fall Of The Turkish Empire. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-688-08093-6.

- Murr Nehme, Lina (2003). 1453: The Fall of Constantinople. Aleph Et Taw. ISBN 2868398162.

- Silburn, P. A. B. (1912). The evolution of sea-power. London: Longmans, Green and Co.

- Dyer, T. H., & Hassall, A. (1901). A history of modern Europe From the fall of Constantinople. London: G. Bell and Sons.

- Fredet, Peter (1888). Modern History; From the Coming of Christ and Change of the Roman Republic into an Empire, to the Year of Our Lord 1888. Baltimore: J. Murphy & Co. Page 383+

- Footnotes

- ^ "Dates of Epoch-Making Events", The Nuttall Encyclopaedia. (Gutenberg version)

- ^ Related to the Mahomet archaisms used for Mohammad. See Medieval Christian view of Muhammad for more information.

- ^ ^ الشقائق النعمانية في علماء الدولة العثمانية، صفحة 52 نقلاً عن تاريخ الدولة العثمانية، صفحة 43

- ^ الفتوح الإسلامية عبر العصور، د. عبد العزيز العمري، صفحة 358-359

- ^ تاريخ الدولة العليّة العثمانية، تأليف: الأستاذ محمد فريد بك المحامي، تحقيق: الدكتور إحسان حقي، دار النفائس، الطبعة العاشرة: 1427 هـ - 2006 م، صفحة: 157 ISBN 9953-18-084-9

- ^ a b Edmonds, Anna. Turkey's religious sites. Damko. p. 1997. ISBN 9758227009. http://books.google.com/books?ei=2do8TIGfMKOcOISUsJsP&ct=result&hl=en&id=xVbkAAAAMAAJ&dq=Gülbahar+Albanian&q=An+Albanian+by+birth,+legend+also+has+it+that+Gulbahar+Hatun+was+a+French+princess+kidnapped+for+the+sultan's+harem.#search_anchor.

- ^ a b Babinger, Franz (1992). Mehmed the Conqueror and His Time. Princeton University Press. p. 51. ISBN 0691010781. http://books.google.com/books?id=PPxC6rO7vvsC&pg=PA175&dq=Kladas+%2B+Albanian&hl=en&ei=TtY8TIrFJ4SoOKbF1Y8P&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CCoQ6AEwATgK#v=onepage&q=Albanian&f=false.

- ^ a b c Silburn, P. A. B. (1912).

- ^ a b Norwich, John Julius (1995). Byzantium:The Decline and Fall. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 81–82. ISBN 0-679-41650-1.

- ^ Runciman, Steven (1965). The Fall of Constantinople: 1453. London: Cambridge University Press. pp. 56. ISBN 0-521-39832-0.

- ^ Haddad, GF. "Conquest of Constantinople". http://www.sunnah.org/msaec/articles/Constantinople.htm. Retrieved August 4, 2006.

- ^ Turks.org.uk

- ^ Crowley, Roger (2006). Constantinople: The Last Great Siege, 1453. Oxford: A.P.R.I.L. Publishing.

- ^ Steven Runciman, The Fall of Constantinople 1453. Cambridge University Press, 1965.

- ^ John R. Melville-Jones, "The Siege of Constantinople 1453: Seven Contemporary Accounts"

- ^ a b Andrews, Walter G.; Mehmet Kalpaklı (2005). The Age of Beloveds: Love and the Beloved in Early Modern Ottoman and European Culture and Society. Duke University Press. pp. 2. ISBN 0822334240.

- ^ http://www.exploringromania.com/young-dracula-childhood.html

- ^ Mehmed the Conqueror and his time pp. 204-5

- ^ Dracula: Prince of many faces - His life and his times p. 147

- ^ Wedding portrait, Nauplion.net

- ^ 1453: The Holy War for Constantinople and the Clash of Islam and the West, Roger Crowley, 2005

- ^ culturecityistanbul.blogspot.com/2009/10/fatih-sultan-mehmed-mausoleum.html.

- ^ تاريخ الدولة العليّة العثمانية، تأليف: الأستاذ محمد فريد بك المحامي، تحقيق: الدكتور إحسان حقي، دار النفائس، الطبعة العاشرة: 1427 هـ - 2006 م، صفحة: 177-178 ISBN 9953-18-084-9

- ^ Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey. Banknote Museum: 7. Emission Group - One Thousand Turkish Lira - I. Series & II. Series. – Retrieved on 20 April 2009.

- ^ # Finkel, Caroline, Osman's Dream, (Basic Books, 2005), 57; "Istanbul was only adopted as the city's official name in 1930..".

- ^ BYU.edu; ARTICLE 91 - All grants of patents and registrations of trade-marks, as well as all registrations of transfers or assignments of patents or trade marks which have been duly made since the 30th October, 1918, by the Imperial Ottoman Government at Constantinople or elsewhere.

- ^ Croatia and Ottoman Empire, Ahdnama, Sultan Mehemt II

- ^ Light Millennium: A Culture of Peaceful Coexistence: The Ottoman Turkish Example; by Prof. Dr. Ekmeleddin IHSANOGLU

External links

- Biography page at OttomanOnline

- Contemporary portraits

- Chapter LXVIII: Reign Of Mahomet The Second, Extinction Of Eastern Empire by Edward Gibbon

Mehmed IIBorn: March 30, 1432 Died: May 3, 1481[aged 49]Regnal titles Preceded by

Murad IISultan of the Ottoman Empire

1444–1446Succeeded by

Murad IIPreceded by

Murad IISultan of the Ottoman Empire

Feb 3, 1451 – May 3, 1481Succeeded by

Bayezid IITitles in pretence Preceded by

Constantine XI— TITULAR —

Caesar of Rome

(Roman Emperor)

1444–1446Succeeded by

Bayezid IIOttoman Sultans / Caliphs Osman I · Orhan · Murad I · Bayezid I · Interregnum · Mehmed I · Murad II · Mehmed II · Murad II · Mehmed II · Bayezid II · Selim I · Suleiman I · Selim II · Murad III · Mehmed III · Ahmed I · Mustafa I · Osman II · Mustafa I · Murad IV · Ibrahim · Mehmed IV · Suleiman II · Ahmed II · Mustafa II · Ahmed III · Mahmud I · Osman III · Mustafa III · Abdülhamid I · Selim III · Mustafa IV · Mahmud II · Abdülmecid I · Abdülaziz · Murad V · Abdülhamid II · Mehmed V · Mehmed VI · Abdülmecid II (Caliph)Related Templates: Claimants · Valide SultansCategories:- Mehmed II

- 1432 births

- 1481 deaths

- 1481 crimes

- East–West Schism

- Medieval child rulers

- Murdered monarchs

- Rulers deposed as children

- People from Edirne

- People illustrated on Turkish banknotes

- 15th-century caliphs

- 15th-century Ottoman sultans

- Deaths by poisoning

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.