- Trepanning

-

"Trepanation" redirects here. For other uses, see Trepanation (disambiguation).

A detail from "The Extraction of the Stone of Madness", a painting by Hieronymus Bosch depicting trepanation (c.1488-1516)

A detail from "The Extraction of the Stone of Madness", a painting by Hieronymus Bosch depicting trepanation (c.1488-1516)

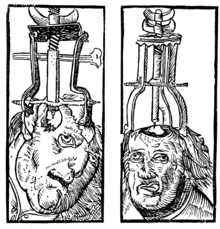

Trepanning, also known as trephination, trephining or making a burr hole, is a surgical intervention in which a hole is drilled or scraped into the human skull, exposing the dura mater in order to treat health problems related to intracranial diseases. It may also refer to any "burr" hole created through other body surfaces, including nail beds. It is often used to relieve pressure beneath a surface. A trephine is an instrument used for cutting out a round piece of skull bone.

Evidence of trepanation has been found in prehistoric human remains from Neolithic times onward. Cave paintings indicate that people believed the practice would cure epileptic seizures, migraines, and mental disorders.[1] The bone that was trepanned was kept by the prehistoric people and may have been worn as a charm to keep evil spirits away. Evidence also suggests that trepanation was primitive emergency surgery after head wounds[2] to remove shattered bits of bone from a fractured skull and clean out the blood that often pools under the skull after a blow to the head. Such injuries were typical for primitive weaponry such as slings and war clubs.[3]

There is some contemporary use of the term. In modern eye surgery, a trephine instrument is used in corneal transplant surgery. The procedure of drilling a hole through a fingernail or toenail is also known as trephination. It is performed by a physician or surgeon to relieve the pain associated with a subungual hematoma (blood under the nail); a small amount of blood is expressed through the hole and the pain associated with the pressure is partially alleviated.

Contents

History

Trepanated skull, Iron age. The perimeter of the hole in the skull is rounded off by ingrowth of new bony tissue, indicating that the patient survived the operation.

Trepanated skull, Iron age. The perimeter of the hole in the skull is rounded off by ingrowth of new bony tissue, indicating that the patient survived the operation.

Dr. John Clarke trepanning a skull, ca. 1664, in one of the earliest American portraits. Clarke was allegedly the first physician to perform the operation in the U.S.

Dr. John Clarke trepanning a skull, ca. 1664, in one of the earliest American portraits. Clarke was allegedly the first physician to perform the operation in the U.S.

Prehistoric evidence

Trepanation is perhaps the oldest surgical procedure for which there is forensic evidence,[4] and in some areas may have been quite widespread. Out of 120 prehistoric skulls found at one burial site in France dated to 6500 BC, 40 had trepanation holes.[5] Many prehistoric and premodern patients had signs of their skull structure healing; suggesting that many of those subjected to the surgery survived.

Pre-Columbian Mesoamerica

Main article: Trepanation in MesoamericaIn pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, evidence for the practice of trepanation and an assortment of other cranial deformation techniques comes from a variety of sources, including physical cranial remains of pre-Columbian burials, allusions in iconographic artworks and reports from the post-colonial period.

Among New World societies, trepanning is most commonly found in the Andean civilizations such as the pre-Incan culture such as the Paracas Ica situated in what now is Ica located South of Lima. Its prevalence among Mesoamerican civilizations is much lower, at least judging from the comparatively few trepanated crania that have been uncovered.[6]

The archaeological record in Mesoamerica is further complicated by the practice of skull mutilation and modification carried out after the death of the subject, to fashion "trophy skulls" and the like of captives and enemies. This was a widespread tradition, illustrated in pre-Columbian art that occasionally depicts rulers adorned with or carrying the modified skulls of their defeated enemies, or of the ritualistic display of sacrificial victims. Several Mesoamerican cultures used a skull-rack (known by its Nahuatl term, tzompantli ), on which skulls were impaled in rows or columns of wooden stakes. Even so, some evidence of genuine trepanation in Mesoamerica (i.e., where the subject was living) has survived.

The earliest archaeological survey published of trepanated crania was a late 19th-century study of several specimens recovered from the Tarahumara mountains by the Norwegian ethnographer Carl Lumholtz.[6][7] Later studies documented cases identified from a range of sites in Oaxaca and central Mexico, such as Tilantongo, Oaxaca and the major Zapotec site of Monte Albán. Two specimens from the Tlatilco civilization's homelands (which flourished around 1400 BC) indicate the practice has a lengthy tradition.[8]

A study of ten low-status burials from the Late Classic period at Monte Albán concluded that the trepanation had been applied non-therapeutically, and, since multiple techniques had been used and since some people had received more than one trepanation, concluded it had been done experimentally. Inferring the events to represent experiments on people until they died, the study interpreted that use of trepanation as an indicator of the stressful sociopolitical climate that not long thereafter resulted in the abandonment of Monte Alban as the primary regional administrative center in the Oaxacan highlands.[citation needed]

Specimens identified from the Maya civilization region of southern Mexico, Guatemala and the Yucatán Peninsula show no evidence of the drilling or cutting techniques found in central and highland Mexico. Instead, the pre-Columbian Maya apparently used an abrasive technique that ground away at the back of the skull, thinning the bone and sometimes perforating it, similar to the examples from Cholula. Many skulls from the Maya region date from the Postclassic period (ca. 950–1400), and include specimens found at Palenque in Chiapas, and recovered from the Sacred Cenote at the prominent Postclassic site of Chichen Itza in northern Yucatán.[9]

Pre-modern Europe

Trepanation was also practiced in the classical and Renaissance periods. Hippocrates gave specific directions on the procedure from its evolution through the Greek age, and Galen also elaborates on the procedure. During the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, trepanation was practiced as a cure for various ailments, including seizures and skull fractures. Out of eight skulls with trepanations from the 6th to 8th centuries found in southwestern Germany, seven skulls show clear evidence of healing and survival after trepanation suggesting that the survival rate of the operations was high and the infection rate was low.[2]

In the graveyards of pre-Christian (Pagan) Magyars, archeologists found a surprisingly high frequency (12.5%) of skulls with trepanation.[10] The trepanation was performed on adults only, with similar frequencies for males and females, but increasing frequency with age and wealth. This custom suddenly disappears with the onset of Christian era.

Modern medical practices

Trepanation is a treatment used for epidural and subdural hematomas, and for surgical access for certain other neurosurgical procedures, such as intracranial pressure monitoring. Modern surgeons generally use the term craniotomy for this procedure. The removed piece of skull is typically replaced as soon as possible. If the bone is not replaced, then the procedure is considered a craniectomy. Trepanation instruments are now available with diamond coated rims (Diamond Bone Cutting System), which are less traumatic than the classical trephines with sharp teeth. They are smooth to soft tissues and cut only bone.

Voluntary trepanation

Although widely considered today to be pseudoscience, the practice of trepanation for other purported medical benefits continues. Moreover, some proponents point to recent research on the increase in cranial compliance following on trepanation, with resulting increase in blood flow,[11] as providing some justification for the practice. Individuals have practiced non-emergency trepanation for psychic purposes. A prominent proponent of the modern view is Peter Halvorson, who drilled a hole in the front of his own skull to increase "brain blood volume".[5]

The most prominent folk theory for the benefits of self-trepanation is offered by Bart Huges (alternatively spelled Bart Hughes and sometimes called "Dr. Bart Hughes", although he did not complete his medical degree). Hughes claims that trepanation increases "brain blood volume" and thereby enhances cerebral metabolism in a manner similar to cerebral vasodilators such as ginkgo biloba. No published results have supported these claims.

In a chapter of his book, Eccentric Lives & Peculiar Notions, John Michell cites Huges as pioneering the idea of trepanation in his 1962 monograph, Homo Sapiens Correctus, which is most often cited by advocates of self-trepanation. Among other arguments, Huges contends that children have a higher state of consciousness and since children's skulls are not fully closed one can return to an earlier, childlike state of consciousness by self-trepanation. Further, by allowing the brain to freely pulsate Huges argues that a number of benefits will accrue.

Michell quotes a book called Bore Hole written by Joey Mellen. At the time the passage below was written, Joey and his partner, Amanda Feilding, had made two previous attempts at trepanning Mellen. The second attempt ended up placing Mellen in the hospital, where he was reprimanded severely and sent for psychiatric evaluation. After he returned home, Mellen decided to try again. He describes his third attempt at self-trepanation:

After some time there was an ominous sounding schlurp and the sound of bubbling. I drew the trepan out and the gurgling continued. It sounded like air bubbles running under the skull as they were pressed out. I looked at the trepan and there was a bit of bone in it. At last!

Feilding also performed a self-trepanation with a drill, while Mellen shot the operation for the film Heartbeat in the Brain, which has since been lost. Portions of the film can be seen, however, in the documentary A Hole in the Head.

Michell also describes a British group that advocates self-trepanation to allow the brain access to more space and oxygen. Other modern practitioners of trepanation claim that it holds other medical benefits, such as a treatment for depression or other psychological ailments. In 2000, two men from Cedar City, Utah were prosecuted for practicing medicine without a license after they performed a trepanation on an English woman to treat her chronic fatigue syndrome and depression.[12]

In popular culture

- Films

- In the movie Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World a trepanation is performed on a crew member by the ship's doctor, with the hole filled by using a coin.

- In the movie π, the protagonist Max Cohen cures his headaches by performing a trepanation on his right temple.

- In the movie Ghostbusters, Peter Venkman mentions that Egon Spengler had attempted self-trepanation prior to the events of the movie. Peter notes that Egon "tried to drill a hole through [his] head," to which Egon replies, "That would have worked if you hadn't stopped me."

- Filmmaker John Waters advocated trepanation in a 2011 interview, saying that it would be a "nice Christmas present" and a way to be "high forever."[13]

- Television

- In the episode Orison of the seventh season of The X-Files, reverend Orison is said to have drilled holes in his skull to boost his mental capabilities and so he could perform certain mental tricks one of which is called "stopping the world."

- In the television series Dead Like Me, the character Mason, played by Callum Blue, died in 1966 by drilling a hole in his head to achieve "the permanent high."

- In the television series Bones, Dr. Brennan and Zack Addy notice a skull with an abnormal hole in it. They realize that the person had undergone trepanation before passing away.

- In the episode "Live Show" of 30 Rock, Dr. Leo Spaceman has an informational brochure entitled "Trepanation" on his desk.

- In the episode "Demons" of Stargate SG-1, A villager on a planet visited by Jack O'Neill is about to perform a trepanation on his niece.

- In an episode of Grey's Anatomy, Izzie makes some "burr-holes" to save a man's life

- In an episode of Rome, the character Titus Pullo requires the operation after a head injury sustained during a barroom brawl.

- In an episode of House MD, Dr. House directs a mechanic at a research facility in Antarctica through the procedure to relieve the internal swelling in the facility doctor's head.

- In an episode of Strangers with Candy, the character Jerri Blank uses a hand drill to "free the beasties" from the head of her crazy stepfather, Stew by drilling into his temple.

- In an episode of Doc Martin ("On the Edge, Pt. 2"), Doc Martin saves someone's life by performing an emergency trepanation.

- Literature

- In the His Dark Materials series by Philip Pullman, trepanation is referenced as a method to draw Dust, the agent of human consciousness and creativity, to the trepanned person in greater quantity. The character Jopari underwent trepanation in becoming a shaman among the Tartars.

- Trepanning is featured in the 2011 novel Bible of the Dead by Tom Knox

- The Vertigo Comics graphic novel Area 10 by Christos N. Gage and Chris Samnee revolves around a serial killer who performs trepanations on his victims.[14]

- Video games

- In the video game Tales of Monkey Island - The Trial and Execution of Guybrush Threepwood, Guybrush uses an "Auto-trepanation" device.

- In the video game Fable III, a poster promoting the benefits of trepanning explains that it can stop "unclean" thoughts.

- In the 2011 video game Alice: Madness Returns, Alice undergoes a trepanation by Tweedle-dum and Tweedle-dee

- In the 2010 video game Fallout: New Vegas, the Courier sarcastically recommends trepanation to treat Michael Angelo's agoraphobia.

- In the 1998 video game Fallout 2, Sulik tells The chosen one to "go see shaman, get hole in head...big hole...very big...huge!" If the PC has a low intelligence.

- Other

- The Dance Gavin Dance album Happiness contains a song entitled "Self-Trepanation".

- In the Japanese manga Homunculus, Susumu Nakoshi, the protagonist, has trepanation performed on himself for money. Afterwards, he finds that when he covers or closes his right eye he can see a person's homunculus.

See also

References

- Notes

- ^ Brothwell, Don R. (1963). Digging up Bones; the Excavation, Treatment and Study of Human Skeletal Remains. London: British Museum (Natural History). pp. 126. OCLC 14615536.

- ^ a b Weber, J.; and A. Czarnetzki (2001). "Trepanationen im frühen Mittelalter im Südwesten von Deutschland - Indikationen, Komplikationen und Outcome" (in German). Zentralblatt für Neurochirurgie 62 (1): 10. doi:10.1055/s-2001-16333.

- ^ The Skull Doctors - www.trepanation.com

- ^ Capasso, Luigi (2002) (in Italian). Principi di storia della patologia umana: corso di storia della medicina per gli studenti della Facoltà di medicina e chirurgia e della Facoltà di scienze infermieristiche. Rome: SEU. ISBN 8887753652. OCLC 50485765.

- ^ a b Restak, Richard (2000). "Fixing the Brain". Mysteries of the Mind. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society. ISBN 0-792-27941-7. OCLC 43662032.

- ^ a b Tiesler Blos, Vera (2003) (PDF). Cranial Surgery in Ancient Mesoamerica. Mesoweb. http://www.mesoweb.com/features/tiesler/Cranial.pdf. Retrieved 2006-05-23.

- ^ Lumholtz, Carl (1897). "Trephining in Mexico". American Anthropologist 10 (12): 389. doi:10.1525/aa.1897.10.12.02a00010.

- ^ Romero Molina, Javier (1970). "Dental Mutilation, Trephination, and Cranial Deformation". In T. Dale Stewart (volume ed.). Handbook of Middle American Indians, Vol. 9: Physical Anthropology. Robert Wauchope (series ed.) (2nd. edition (revised) ed.). Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-70014-8. OCLC 277126.

- ^ Tiesler Blos, Vera (1999) (in Spanish). Rasgos Bioculturales Entre los Antiguos Mayas: Aspectos Culturales y Sociales. Doctoral thesis in Anthropology, UNAM.

- ^ http://sirasok.blog.hu/2008/09/10/agyafurt_magyarok_koponylekeles_a_honfoglalaskorban

- ^ http://www.newscientist.com/article/mg20227121.400-like-a-hole-in-the-head-the-return-of-trepanation.html?full=true

- ^ Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press (2000) ABC ordered to hand over unedited head-drilling tapes

- ^ "This Much I Know: John Waters". The Guardian. 15 May 2011. http://www.guardian.co.uk/lifeandstyle/2011/may/15/this-much-know-john-waters.

- ^ "'Area 10': You Need This Comic Like a Hole in the Head (Review)". comicsalliance.com. 2011-05-15. http://www.comicsalliance.com/2011/05/15/area-10-comic/. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

External links

Categories:- Body modification

- History of neuroscience

- Neurosurgery

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.