- Operation Frequent Wind

-

Operation Frequent Wind was the evacuation by helicopter of American civilians and 'at-risk' Vietnamese from Saigon, South Vietnam, on 29–30 April 1975 during the last days of the Vietnam War. More than 7,000 people were evacuated from various points in Saigon, and the airlift left a number of enduring images.

Preparations for the airlift already existed as a standard procedure for American embassies. In the beginning of March, fixed-wing aircraft began evacuating civilians through neighboring countries. By mid-April, contingency plans were in place and preparations were underway for a possible helicopter evacuation. As the imminent collapse of Saigon became evident, Task Force 76 was assembled off the coast near Vung Tau to support a helicopter evacuation and provide air support if required. Air support was not needed as the North Vietnamese recognized that interfering with the evacuation could provoke a forceful reaction from US forces.

On April 28, Tan Son Nhut Air Base came under artillery fire and attack from Vietnamese People's Air Force aircraft. The fixed-wing evacuation was terminated and Operation Frequent Wind commenced.

The evacuation was to take place primarily from Defense Attaché Office compound and began around two in the afternoon on 29 April and was completed that night with only limited small arms damage to the helicopters. The US Embassy, Saigon was intended to only be a secondary evacuation point for Embassy staff, but was soon overwhelmed with evacuees and desperate South Vietnamese. The evacuation of the Embassy was completed at 07:53 on 30 April, but some 400 third country nationals were left behind.

With the collapse of South Vietnam, an unknown number of VNAF helicopters and some fixed-wing aircraft flew out to the evacuation fleet. Helicopters began to clog ship decks and eventually some were pushed overboard to allow others to land. Pilots of other helicopters were told to drop off their passengers and then take off and ditch in the sea, from where they would be rescued.

During the fixed-wing evacuation 50,493 people (including 2678 Vietnamese orphans) were evacuated from Tan Son Nhut. In Operation Frequent Wind a total of 1,373 Americans and 5,595 Vietnamese or third country nationals were evacuated by helicopter.

Contents

- 1 Planning

- 2 Preparations on the ground

- 3 Options 1 and 2 - fixed-wing evacuation

- 4 Task Force 76

- 5 Tan Son Nhut under attack

- 6 Option 4 - White Christmas in April

- 7 Security and air support

- 8 Air America

- 9 The DAO compound

- 10 The Embassy

- 11 Chaos at sea

- 12 Results of the evacuation

- 13 Casualties

- 14 Memorials

- 15 The photo

- 16 In popular culture

- 17 References

- 18 Further reading

- 19 External links

Planning

Evacuation plans are standard for most American embassies, the Talon Vise/Frequent Wind plan had been built up over a number of years.[1] "Frequent Wind" was the second code name chosen when the original code name "Talon Vise" was compromised.[2]

By 1975 the Talon Vise/Frequent Wind plan had a figure of approximately 8000 US citizens and third country nationals to be evacuated, but were never able to conclude a figure for the number of South Vietnamese to be evacuated.[3] There were approximately 17,000 Vietnamese employees on embassy rolls which using an average of seven members per family meant that the number was 119,000 and taken with other categories of Vietnamese the number quickly increased to over 200,000.[4] The Talon Vise/Frequent Wind plan set out four possible evacuation options as follows:[5]

Option 1: Evacuation by commercial airlift from Tan Son Nhut and other South Vietnamese airports as required

Option 2: Evacuation by military airlift from Tan Son Nhut and other South Vietnamese airports as required

Option 3: Evacuation by sea lift from Saigon port

Option 4: Evacuation by helicopter to US Navy ships in the South China Sea

With Option 4, the helicopter evacuation would be expected to closely follow that of Operation Eagle Pull, the American evacuation by air of Phnom Penh, Cambodia, on April 12, 1975.[6] Operation Eagle Pull had been a huge success in terms of meeting all goals set out by military planners.

Preparations on the ground

On 1 April an Evacuation Control Center manned by Army, Navy, USAF and USMC personnel began operating at the Defense Attaché Office compound on 12 hour shifts, increasing to 24 hour shifts the next day.[7] Also on 1 April Plan Alamo was implemented to utilize and defend the DAO compound and Annex as an evacuee holding area, intended to care for 1500 evacuees for 5 days.[8] By 16 April, Alamo was complete, water, C-rations and petroleum, oil and lubricants had been stockpiled, power-generating facilities had been duplicated, sanitary facilities were completed and concertina wire protected the perimeter.[9]

On 7 April, Air America pilot Nikki A. Fillipi, with Marine Lt Robert Twigger, assigned to the DAO as the Marine Corps liaison officer, surveyed 37 buildings in Saigon as possible landing zones (LZ) selecting 13 of them as fit for use.[10] On 9 April, workers from Pacific Architects and Engineers proceeded to visit each of the 13 LZs to remove obstructions and paint H's the exact dimensions of a Huey helicopters skids on each of the LZs.[11] On 11 April President Gerald Ford in an address to the American public promised to evacuate Vietnamese civilians of various categories. On 12 April, the 9th Marine Amphibious Brigade (9th MAB), which was to supply helicopters and a security force for the evacuation, sent a delegation to consult with Ambassador Graham Martin on current plans. Ambassador Martin told them that he would not tolerate any outward signs that the United States intended to abandon South Vietnam. All planning would have to be conducted with the utmost discretion. Brigadier General Richard E. Carey, commander of the 9th MAB, flew to Saigon the next day to see Ambassador Martin, he later said that ‘The visit was cold, non-productive and appeared to be an irritant to the Ambassador’.[10]

On 13 April, 13 Marines from the Marine Security Guard detachment were deployed to the DAO Compound to replace the 8 Marine Guards withdrawn from the closed Danang and Nha Trang Consulates who had been providing security up to that point.[9]

By late April Air America helicopters were flying several daily shuttles from TF76 to the DAO Compound to enable the 9th MAB to conduct evacuation preparations at the DAO without exceeding the Paris Peace Accords' limit of a maximum of 50 military personnel in South Vietnam, this at a time when the North Vietnamese army was overtly breaching the Peace Accords.[12]

The two major evacuation points chosen for Operation Frequent Wind were the DAO Compound adjacent to Tan Son Nhut Airport for American civilian and Vietnamese evacuees and the US Embassy, Saigon for Embassy staff.[13] The plan for the evacuation would see convoy buses prestaged throughout metropolitan Saigon at 28 buildings designated as pick-up points with American civilians, trained to drive those buses, standing by in town at the way stations. The buses would follow one of 4 planned evacuation routes from downtown Saigon to the DAO Compound, each route named after a Western Trail so there was Santa Fe, Oregon, Texas etc.[14][15]

Options 1 and 2 - fixed-wing evacuation

By late March the Embassy began a thinning out of US citizens in Vietnam by encouraging dependents and non-essential personnel to leave the country by commercial flights and on Military Airlift Command C-141 and C-5 aircraft which were still flying in emergency military supplies.[16] In late March 2 or 3 MAC aircraft were arriving each day and these aircraft were used for the evacuation of civilians or as part of Operation Babylift.[17] On 4 April a C-5A aircraft carrying 250 Vietnamese orphans and their escorts suffered explosive decompression over the sea near Vung Tau and made a crash-landing while attempting to return to Tan Son Nhut; 153 died in the crash.[18]

Following the C-5 crash, and with the cause still unknown, the C-5 fleet was grounded and the MAC airlift was reduced to using C-141s and C-130s and rather than combat loading, each evacuee required a seat and a seatbelt reducing the number of passengers that could be carried on each flight. Each C-141 would carry 94 passengers while each C-130 would carry 75, although these requirements were relaxed then ignored altogether as the pace of the evacuation quickened.[19] Armed guards were also present on each flight to prevent the possibility of hijacking.[20] American commercial and contract carriers continued to fly out of Tan Son Nhut, but with decreasing frequency. In addition, military aircraft from Australia, Indonesia, Iran, Poland and others flew in to evacuate their Embassy personnel.[20]

Throughout April the "thinning out" proceeded slowly largely due to difficulties experienced by Americans in obtaining the necessary paperwork from the South Vietnamese Government to enable them to take their Vietnamese dependents with them, with the result that MAC aircraft were often departing empty.[21] Finally on 19 April a simple procedure was implemented that cleared up the paperwork jam and the number of evacuees dramatically increased from 20 April onwards.[22] The fall of Xuân Lộc on 20 April and the resignation of President Nguyễn Văn Thiệu on 21 April brought greater crowds seeking evacuation to the DAO Compound as it became apparent that South Vietnam's days were numbered. By 22 April 20 C-141 and 20 C-130s flights were flying evacuees out of Tan Son Nhut to Clark Air Base.[23] On 23 April President Ferdinand Marcos of the Philippines announced that no more than 2500 Vietnamese evacuees would be allowed in the Philippines at any one time, further increasing the strain on MAC which now had to move evacuees out of Saigon and move some 5000 evacuees from Clark Air Base on to Guam, Wake Island and Yokota Air Base.[24] On 25 April 1975 a USAF C-118 transport left Tan Son Nhut carrying former President Thieu and his family to exile in Taiwan, Thiệu had resigned 4 days earlier.[25] Also on 25 April the Federal Aviation Authority banned commercial flights into South Vietnam. However, this directive was subsequently reversed while some operators had ignored it anyway. In any case this effectively marked the end of the commercial airlift from Tan Son Nhut.[26]

On 27 April NVA rockets hit Saigon and Cholon for the first time since the 1973 ceasefire. It was decided that from that time only C-130s would be used for the evacuation due to their greater manoevurability. There was relatively little difference between the cargo loads of the two aircraft, C-141s had been loaded with up to 316 evacuees while C-130s had been taking off with in excess of 240.[19]

Task Force 76

USAF CH-53 helicopters on the deck of USS Midway during Operation Frequent Wind, April 1975.

USAF CH-53 helicopters on the deck of USS Midway during Operation Frequent Wind, April 1975.

Between 18 and 24 April 1975, with the fall of Saigon imminent, the Navy concentrated off Vung Tau a vast assemblage of ships under Commander Task Force 76 comprising:[6]

Task Force 76 USS Blue Ridge (command ship)

Task Group 76.4 (Movement Transport Group Alpha)

Task Group 76.5 (Movement Transport Group Bravo)

Task Group 76.9 (Movement Transport Group Charlie)

The task force was joined by:

each carrying Marine, and Air Force (8 21st Special Operations Squadron CH-53s and 2 40th Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Squadron HH-53s[27]) helicopters.

Seventh Fleet flagship USS Oklahoma City.

Amphibious ships:

and eight destroyer types for naval gunfire, escort, and area defense, including:

- USS Richard B. Anderson

- USS Cochrane

- USS Kirk

- USS Gurke

- USS Rowan

- USS Cook[citation needed]

- USS Bausell[28]

The USS Enterprise and USS Coral Sea carrier attack groups of Task Force 77 in the South China Sea provided air cover while Task Force 73 ensured logistic support.

The Marine evacuation contingent, the 9th Marine Amphibious Brigade (Task Group 79.1), consisted of three battalion landing teams; 2nd Battalion, 4th Marines (2/4), 2nd Battalion 9th Marines (2/9), 3rd Battalion 9th Marines (3/9) and three helicopter squadrons HMH-462, HMH-463, HMM-165 along with other support units from Marine Aircraft Group 39 (MAG-39).

Tan Son Nhut under attack

On 28 April at 18:06 3 A-37 Dragonflys piloted by former VNAF pilots who had defected to the Vietnamese People's Air Force at the fall of Danang dropped 6 Mk81 250 lb bombs on the VNAF flightline at Tan Son Nhut Air Base destroying several aircraft. VNAF F-5s took off in pursuit, but were unable to intercept the A-37s.[29] C-130s leaving Tan Son Nhut reported receiving 0.51 cal and 37mm ground fire,[30] while sporadic PAVN rocket and artillery attacks also started to hit the airport. C-130 flights were stopped temporarily after the air attack but resumed at 20:00 on 28 April.[31] At 21:00 on 28 April Major General Homer D Smith Jr, the senior Defence Attache informed the Evacuation Control Center that 60 C-130 flights would come in on 29 April to evacuate 10,000 people.[32]

At 03:30 on 29 April a PAVN rocket hit Guardpost 1 at the DAO Compound, instantly killing Marine Corporals McMahon and Judge. They would be the last American ground casualties in Vietnam.[33]

At 03:58, C-130E Hercules, 72-1297, c/n 4519, of the 314th Airlift Wing and flown by a crew from the 776th Tactical Airlift Squadron, 374th Tactical Airlift Wing out of Clark Air Base, Philippines, was destroyed by a 122mm rocket shortly after having offloaded a BLU-82 at Tan Son Nhut Air Base and taxiing to pick up evacuees. The crew evacuated the burning aircraft on the taxiway and departed the airfield on another C-130 that had previously landed.[34] This would be the last USAF fixed-wing aircraft to leave Tan Son Nhut.[35] Between 04:30 and 08:00 up to 40 artillery rounds and rockets hit around the DAO Compound.[36]

At dawn the VNAF began to haphazardly depart Tan Son Nhut Air Base as A-37s, F-5s, C-7s, C-119s and C-130s departed for Thailand while UH-1s took off in search of the ships of TF-76.[37] Some VNAF aircraft did stay to continue to fight the advancing NVA however. One AC-119 gunship had spent the night of 28/29 April dropping flares and firing on the approaching NVA. At dawn on 29 April two A-1 Skyraiders began patrolling the perimeter of Tan Son Nhut at 2500 feet until one was shot down, presumably by an SA-7. At 07:00 the AC-119 was firing on NVA to the east of Tan Son Nhut when it too was hit by an SA-7 and fell in flames to the ground.[38]

At 07:00 on 29 April, Major General Smith advised Ambassador Martin that fixed wing evacuations should cease and that Operation Frequent Wind, the helicopter evacuation of US personnel and at-risk Vietnamese should commence. Ambassador Martin refused to accept General Smith's recommendation and instead insisted on visiting Tan Son Nhut to survey the situation for himself. At 10:00 Ambassador Martin confirmed General Smith's assessment and at 10:48 he contacted Washington to recommend Option 4, the helicopter evacuation.[39] Finally at 10:51 the order was given by CINCPAC to commence Option 4, however due to confusion in the chain of command General Carey did not receive the execute order until 12:15.[40] At 08:00 Lieutenant General Minh, commander of the VNAF and 30 of his staff arrived at the DAO compound demanding evacuation, this signified the complete loss of command and control of the VNAF.[41]

Option 4 - White Christmas in April

In preparation for the evacuation, the American embassy had distributed a 15-page booklet called SAFE, short for "Standard Instruction and Advice to Civilians in an Emergency." The booklet included a map of Saigon pinpointing "assembly areas where a helicopter will pick you up." There was an insert page which read: "Note evacuational signal. Do not disclose to other personnel. When the evacuation is ordered, the code will be read out on Armed Forces Radio. The code is: The temperature in Saigon is 112 degrees and rising. This will be followed by the playing of I'm Dreaming of a White Christmas." Frank Snepp later recalled the arrival of helicopters at the embassy while the song was playing over the radio as a "bizarre Kafkaesque time".[42] Japanese journalists, concerned that they would not recognize the tune, had to get someone to sing it to them.[43]

In the run up to the evacuation, thousands of South Vietnamese supporters wanted to leave the city. With so many desperate people and so many civilians in knowledge of security codes, it is likely that security was broken almost as soon as the code song was given out. In any event the sudden movement of hundreds of Westerners and thousand of high-ranking Vietnamese would not have gone unnoticed for long.[citation needed]

After the evacuation signal was given the buses began to pick up passengers and head to the DAO compound. The system worked so efficiently that the buses were able to make 3 return journeys rather than the expected one. The biggest problem occurred when the ARVN guarding the main gate at Tan Son Nhut refused to allow the last convoy of buses into the DAO compound at about 17:45. As this was happening, a firefight between two ARVN units broke out and caught the rearmost buses in the crossfire, disabling two of the vehicles. Eventually the ARVN commander controlling the gates agreed to permit the remaining buses to enter the compound. General Carey's threat to use the AH-1J SeaCobras flying overhead may have played a role in the ARVN commander's decision.[44]

Security and air support

It was not known whether the PAVN and/or the ARVN would try to disrupt the evacuation and so the planners had to take all possible contingencies into account to ensure the safety and success of the evacuation. The staff of 9th MAB prescribed altitudes, routes, and checkpoints for flight safety for the operation. To avert mid-air collisions, the planners chose altitudes which would not only provide separation of traffic but also a capability to see and avoid the enemy's AAA, SA-2 and SA-7 missile threat (6,500 feet for flights inbound to Saigon and 5,500 feet for those outbound from Saigon to the Navy ships). In addition, these altitudes were high enough to avoid small arms and artillery fire.[45]

In the event that the PAVN or ARVN shot down a helicopter or a mechanical malfunction forced one to make an emergency landing in hostile territory, 2 orbiting CH-46s of MAG-39 each carried 15-man, quick-reaction "Sparrow Hawk" teams of Marines from Company A, 1st Battalion, 9th Marines, ready to land and provide security enabling a search and rescue (SAR) helicopter to pick up the crew. In addition, two CH-46s would provide medical evacuation capabilities while AH-1J Sea-cobras would fly cover for the transport helicopters and for any ground units who requested support. The Sea-cobras could also serve as Tactical Air Coordinators (Airborne) or Forward Air Controllers (Airborne).[46]

The air wings of the USS Enterprise and USS Coral Sea, were ready to provide close air support and SEAD if required with their A-6 and A-7 attack aircraft, and would provide continuous fighter cover the evacuation route including by VF-1 and VF-2, flying from the Enterprise with the first combat deployment of the new F-14 Tomcat.[47] USAF aircraft operating out of Nakhon Phanom Air Base, Korat Air Base and U-Tapao Air Base in Thailand were also overhead for the duration of the helicopter evacuation. A C-130 Airborne Command and Control controlled all US air operations over land. USAF F-4s, F-111s and A-7s provided air cover during daylight, being replaced by AC-130s from the 16th Special Operations Squadron at night. Strategic Air Command KC-135 tankers provided air-to-air refueling.[48]

In fact the evacuation was allowed to proceed without molestation from the PAVN. Aircraft flying air cover for the evacuation reported being tracked with surface to air radar in the vicinity of Bien Hoa Air Base (which had fallen to the NVA on 25 April), but no missile launches took place.[49] The Hanoi leadership, reckoning that completion of the evacuation would lessen the risk of American intervention, had apparently instructed General Dũng not to target the airlift itself.[50] Members of the police in Saigon had been promised evacuation in exchange for protecting the American evacuation buses and control of the crowds in the city during the evacuation.[51] American helicopters were repeatedly hit by small arms fire from disgruntled ARVN troops throughout the evacuation without causing serious damage. Despite receiving AAA fire, no attacks were made by USAF or USN aircraft on AAA or SAM sites during the evacuation.[52]

Despite all the concern over these military threats, the weather presented the gravest danger. At the beginning of the operation, pilots in the first wave reported the weather as 2,000 feet (610 m) scattered, 20,000 feet (6,100 m) overcast with 15 miles (24 km) visibility, except in haze over Saigon, where visibility decreased to one mile. This meant that scattered clouds existed below their flight path while a solid layer of clouds more than two miles above their heads obscured the sun, additionally, the curtain of haze, suspended over Saigon, so altered the diminished daylight that line of sight visibility was only a mile. The weather conditions would deteriorate as the operation continued.[45]

Air America

Main article: Air America (airline)As part of the evacuation plan agreed with the DAO, Air America committed 24 of its 28 available helicopters to support the evacuation and 31 pilots agreed to stay in Saigon to support the evacuation; this meant that each helicopter would have only 1 pilot.[53] At 08:30 on 29 April, with the shelling of Tan Son Nhut Airport subsiding, Air America began ferrying its helicopter and fixed wing pilots from their homes in Saigon out to the Air America compound at Tan Son Nhut, across the road from the DAO compound.[54] Air America helicopters started flying to the rooftop LZs in Saigon and either shuttled the evacuees back to the DAO compound or flew out to the ships of TF76.[55] By 10:30 all Air America's fixed-wing aircraft had departed Tan Son Nhut evacuating all non-essential personnel and as many Vietnamese evacuees as they could carry and headed for Thailand.[56] At some point during the morning RVNAF personnel stole 5 ICCS UH1-H Hueys and one Air America Bell 204 from the Air America ramp.[57]

At 11:00 the security situation at the Air America compound was deteriorating as General Carey did not wish to risk his Marines by extending his perimeter to cover the Air America compound (LZ 40), so all Air America helicopters from this time operated out of the tennis courts in the DAO Annex (LZ 35).[55][58] This move created fuel problems for Air America as they no longer had access to the fuel supplies in their compound and at least initially they were refused fuel by the ships of TF76.[59] According to US Naval Archives, at 12:30 an Air America Bell 205 landed Air Vice Marshal Nguyễn Cao Kỳ, Madame Kỳ, Dorothy Martin (wife of Ambassador Martin) and others on the USS Denver, however contemporary reports and photos state that Marshal Kỳ piloted his own UH-1H Huey to the USS Midway.[60]

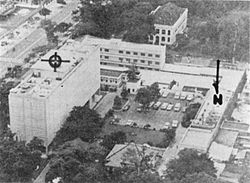

At approximately 14:30, Air America Bell 205 serial number "N47004" landed on the roof of the Pittman Apartment Building at 22 Gia Long Street to collect a senior Vietnamese intelligence source and his family. The Pittman Building wasn't an approved LZ, but when the agreed pickup point at the Lee Hotel at 6 Chien Si Circle was declared unusable, CIA Station Chief Tom Polgar asked Oren B. Harnage, Deputy Chief of the Embassy’s Air Branch to change the pickup to the Pittman Building, which was the home of the Assistant Station Chief and had an elevator shaft that should support the weight of a Huey. Harnage boarded an Air America Huey from the Embassy's rooftop heliport and flew the short distance to the Pittman Building. Harnage leaned out of the Huey and helped approximately 15 evacuees board the Huey from the narrow helipad.[61] The scene was famously captured on film by Hubert van Es (see The Photo below).

Air America helicopters continued to make rooftop pickups until after nightfall by which time navigation became increasingly difficult. Helicopters overflew the designated LZs to check no Americans had been left behind and then the last helicopters (many low on fuel) headed out to TF76, located the USS Midway or the USS Hancock and shut down. All Air America flights had ceased by 21:00.[62] With its available fleet of only 20 Hueys (3 of which were impounded, ditched or damaged at TF76), Air America had moved over 1000 evacuees to the DAO compound, the Embassy or out to the ships of TF76.[63]

The DAO compound

At 14:06 two UH-1E Huey helicopters carrying General Carey and Colonel Gray (commander of Regimental Landing Team 4 (RLT4)) landed at the DAO compound.[64] During their approach to the compound, they experienced a firsthand view of the PAVN's firepower as they shelled nearby Tan Son Nhut Airport with ground, rocket, and artillery fire. They quickly established an austere command post in preparation for the arrival of the Marine CH-53s and the ground security force.[65]

The first wave of 12 CH-53s from HMH-462 loaded with the BLT 2/4's command groups "Alpha" and "Bravo," and Company F and reinforced Company H arrived in the DAO compound at 15:06 and the Marines quickly moved to reinforce the perimeter defenses. As they approached the helicopters had taken rifle and M-79 grenade fire from ARVN troops but without causing any apparent damage.[66] The second wave of 12 CH-53s from HMH-463 landed in the DAO compound at 15:15 bringing in the rest of the BLT. A third wave of two CH-53s from HMH-463 and eight USAF CH-53Cs and two USAF HH-53s of the 40th Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Squadron (all operating from the USS Midway) arrived shortly afterwards.[67]

"Alpha" command group, two rifle companies, and the 81 mm mortar platoon were deployed around the DAO headquarters building (the Alamo) and its adjacent landing zones. Companies E and F respectively occupied the northern and southern sections between the DAO headquarters and the DAO Annex. "Bravo" command group, consisting of two rifle companies and the 106 mm recoilless rifle platoon, assumed responsibility for security of the DAO annex and its adjoining landing zones. Company G occupied the eastern section of the annex, while Company H assumed control of the western section.[68]

The HMH-462 CH-53s loaded with evacuees and left the compound, they unloaded the first refugees delivered by Operation Frequent Wind at 15:40.[69] At about 17:30 General Carey ordered the extraction of 3rd Platoon, Company C of BLT 1/9, which had been landed at the DAO compound on 25 April to assist the Marine Security Guard.[13] Between 19:00 and 21:00 General Carey transferred 3 platoons (130 men) of BLT 2/4 into the embassy compound to provide additional security and assistance for the embassy.[70]

At 19:30 General Carey directed that the remaining elements guarding the annex be withdrawn to DAO headquarters (the Alamo) where the last of the evacuees would await their flight. Once completed, the new defensive perimeter encompassed only LZ 36 and the Alamo. By 20:30 the last evacuees had been loaded onto helicopters.[71] With the evacuation of the landing control teams from the annex and Alamo completed, General Carey ordered the withdrawal of the ground security forces from the DAO compound around 22:50.[71] At 23:40 Marines destroyed the satellite terminal, the DAO compound's last means of direct communication with the outside world.[72] At 00:30 on 30 April, thermite grenades, having been previously placed in selected buildings, ignited as two CH-53s left the DAO parking lot carrying the last elements of 2nd Battalion 4th Marines.[71]

The Embassy

On 25 April 40 Marines from the 9th MAB on the USS Hancock were flown in by Air America helicopters in civilian clothes to the DAO compound to augment the 18 Marine Security Guards assigned to defend the embassy, an additional six Marines were assigned to protect Ambassador Martin. Martin had remained optimistic that a negotiated settlement could be reached whereby the US would not have to pull out of South Vietnam and, in an effort to avert defeatism and panic he specifically instructed Major James Kean, Commanding Officer of the Marine Security Guard Battalion and Ground Support Force Commander United States Embassy Compound, that he could not begin to remove the tamarind tree and other trees and shrubbery which prevented the use of the Embassy parking lot as a helicopter landing zone.[73]

By the morning of 29 April it was estimated that approximately 10,000 people had gathered around the embassy, while some 2,500 evacuees were in the embassy and consular compounds. The crowds prevented the use of buses for transporting evacuees from the Embassy to the DAO Compound for evacuation and the embassy gates were eventually closed to prevent the crowd from surging through. Eligible evacuees would now have to make themselves known to the marine guards or embassy staff manning the walls and they would then be lifted over the walls and into the Embassy compound. Among those arriving at the Embassy were Dr Phan Quang Dan, former Deputy Prime Minister and minister responsible for social welfare and refugee resettlement, an obsessive anti-communist who was constantly making speeches exhorting his countrymen to stand and fight.[74] Lieutenant-General Dang Van Quang "regarded by his countrymen and by many Americans as one of the biggest and richest profiteers in South Vietnam" arrived at the gates of the embassy with three Samsonite suitcases and pockets bulging with US dollars. His name was on the evacuation list and he was lifted over the wall.[75] In addition to such notables were the "beautiful people" of Saigon, including those young men of military age whose wealthy parents had paid large bribes to keep them out of the Army and now were paying even more to evacuate them.[76]

From 10:00 to 12:00 Major Kean and his marines cut down trees and moved vehicles to create an LZ in the embassy parking lot behind the Chancery building. Two LZs were now available in the Embassy compound, the rooftop for UH-1s and CH-46 Sea Knights and the new parking lot LZ for the heavier CH-53s.[77] Air America UH-1s began ferrying evacuees from other smaller assembly points throughout the city and dropping them on the Embassy's rooftop LZ. At 15:00 the first CH-53s were sighted heading towards the DAO compound at Tan Son Nhut. Major Kean contacted the Seventh Fleet to advise them of his airlift requirements, until that time the fleet believed that all evacuees had been bussed from the Embassy to the DAO Compound and that only two helicopters would be required to evacuate Ambassador Martin and the Marines from the Embassy.[78]

The scene inside the Embassy had become surreal. The evacuees had found whatever space was available inside the Embassy compound and evacuees and some staff proceeded to liberate alcohol from the Embassy's stores.[79] From the billowing incinerator on the embassy roof floated intelligence documents and US currency, most charred; some not. An Embassy official said that more than five million dollars were being burned.[80]

At 17:00 the first CH-46 landed at the Embassy. Between 19:00 and 21:00 on 29 April approximately 130 additional Marines from 2nd Battalion 4th Marines were lifted from the DAO Compound to reinforce perimeter security at the Embassy,[70] bringing the total number of Marines at the Embassy to 175.[13] The evacuation from the DAO Compound was completed by about 19:00 after which all helicopters would be routed to the Embassy, however Major Kean was informed that operations would cease at dark. Major Kean advised that the LZ would be well lit and had vehicles moved around the parking lot LZ with their engines running and headlights on to illuminate the LZ.[78] At 21:30 a CH-53 pilot informed Major Kean that Admiral Whitmire, Commander of Task Force 76 had ordered that operations would cease at 23:00. Major Kean saw Ambassador Martin to request that he contact the Oval Office to ensure that the airlift continued. Ambassador Martin soon sent word back to Major Kean that sorties would continue to be flown.[78] At the same time, General Carey met with Admiral Whitmire to convince him to resume flights to the Embassy despite pilot weariness and poor visibility caused by darkness, fires and bad weather.[81]

By 02:15 on 30 April one CH-46 and one CH-53 were landing at the Embassy every 10 minutes. At this time, the Embassy indicated that another 19 lifts would complete the evacuation.[82] At that time Major Kean estimated that there were still some 850 non-American evacuees and 225 Americans (including the Marines), Ambassador Martin told Major Kean to do the best he could.[83] At 03:00 Ambassador Martin ordered Major Kean to move all the remaining evacuees into the parking lot LZ which was the Marines' final perimeter.[83] At 03:27 President Gerald Ford ordered that no more than 19 additional lifts would be allowed to complete the evacuation.[84] At 04:30 with the 19 lift limit already exceeded, Major Kean went to the rooftop LZ and spoke over a helicopter radio with General Carey who advised that Ford had ordered that the airlift be limited to US personnel. Major Kean was then ordered to withdraw his men into the Chancery building and withdraw to the rooftop LZ for evacuation.[83]

Major Kean returned to the ground floor of the Chancery and ordered his men to withdraw into a large semicircle at the main entrance to the Chancery. Most of the Marines were inside the Chancery when the crowds outside the Embassy broke through the gates into the compound. The Marines closed and bolted the Chancery door, the elevators were locked by Seabees on the sixth floor and the Marines withdrew up the stairwells locking grill gates behind them. On the ground floor a water tanker was driven through the Chancery door and the crowd began to surge up through the building toward the rooftop. The Marines on the rooftop had sealed the doors and were using mace to discourage the crowd from trying to break through. Sporadic gunfire from around the Embassy passed over the rooftop.[85]

At 04:58 Ambassador Martin boarded a USMC CH-46 Sea Knight, call-sign "Lady Ace 09" of HMM-165 and was flown to the USS Blue Ridge. When Lady Ace 09 transmitted "Tiger is out," those helicopters still flying thought the mission was complete, thereby delaying the evacuation to the Marines from the Embassy rooftop.[84] CH-46s evacuated the Battalion Landing Team by 07:00 and after an anxious wait a lone CH-46 "Swift 2-2" of HMM-164[84] arrived to evacuate Major Kean and the 10 remaining men of the Marine Security Guards, this last helicopter took off at 07:53 on 30 April and landed on USS Okinawa at 08:30.[86]

At 11:30 PAVN tanks smashed through the gates of the Presidential Palace (now the Reunification Palace) less than 1 km from the embassy and raised the flag of the National Liberation Front for South Vietnam (NLF) over the building; the Vietnam War was over.

Chaos at sea

During the course of the operation an unknown number of VNAF helicopters flew out of what remained of South Vietnam to the fleet. Around 12:00 five or six VNAF UH-1Hs and one of the stolen ICCS UH-1Hs, serial number 69-16715, were circling around the USS Blue Ridge. The VNAF pilots had been instructed after dropping off their passengers to ditch their helicopters and they would then be picked up by the ship's boat. The pilot of the stolen ICCS Huey had been told to ditch off the aft left side of the ship, but seemed reluctant to do so, flying around the ship to the front right side he jumped from his helicopter at a height of 40 feet (12 m). His helicopter turned and hit the side of the USS Blue Ridge before hitting the sea. The tail rotor sheared off and embedded itself in the engine of an Air America Bell 205 that was doing a hot refueling on the helipad at the rear of the ship. The Air America pilot shut down his helicopter and left it and moments later a VNAF UH-1H attempted to land on the helipad, locked rotors with the Air America Bell almost pushing it overboard.[87] The stolen Air America Bell 204, serial number N1305X landed on the USS Kirk, from where it was flown to the USS Okinawa by US Navy pilots.[57]

So many South Vietnamese helicopters landed on the TF76 ships that some 45 UH-1 Hueys and at least one CH-47 Chinook were pushed overboard to make room for more helicopters to land.[88] Other helicopters dropped off their passengers and were then ditched into the sea by their pilots, close to the ships, their pilots bailing out at the last moment to be picked up by rescue boats.[89]

One of the more notable events occurred on the USS Midway when the pilot of a VNAF Cessna O-1 Bird Dog dropped a note on the deck of the carrier, the note read "Can you move these helicopter to the other side, I can land on your runway, I can fly 1 hour more, we have enough time to move. Please rescue me. Major Buang, Wife and 5 child." Midway's CO, Captain L.C. Chambers ordered the flight deck crew to clear the landing area. Once the deck was clear Major Buang approached the deck, bounced once and then touched down and taxied to a halt with room to spare.[90] Major Buang became the first VNAF fixed-wing pilot to ever land on a carrier. A second Cessna O-1 was also recovered by the USS Midway that afternoon.[91]

Results of the evacuation

During the fixed-wing evacuation 50,493 people (including 2,678 Vietnamese orphans) were evacuated from Tan Son Nhut.[92] Marine pilots accumulated 1,054 flight hours and flew 682 sorties throughout Operation Frequent Wind. The evacuation of personnel from the DAO compound had lasted nine hours and involved over 50 Marine Corps and Air Force helicopters. In the helicopter evacuation a total of 395 Americans and 4,475 Vietnamese and third-country nationals were evacuated from the DAO compound[71] and a further 978 U.S. and 1,120 Vietnamese and third-country nationals from the Embassy,[93] giving a total of 1,373 Americans and 5,595 Vietnamese and third country nationals. In addition, Air America helicopters and RVNAF aircraft brought additional evacuees to the TF76 ships. Many of the Vietnamese evacuees were allowed to enter the United States under the Indochina Migration and Refugee Assistance Act. Some 400 evacuees were left behind at the Embassy including over 100 South Korean citizens, among them was General Dai Yong Rhee, former deputy commander of all South Korean forces in Vietnam and subsequently the intelligence chief at the South Korean Embassy in Saigon. The South Korean civilians were evacuated in 1976, while General Rhee and two other diplomats were held captive until April 1980.[94]

While the operation itself was a success, the images of the evacuation symbolized the wastefulness and ultimate futility of American involvement in Vietnam. President Ford later called it "a sad and tragic period in America's history" but argued that "you couldn't help but be very proud of those pilots and others who were conducting the evacuation".[95] Peace With Honor in Vietnam had become a humiliating defeat, which together with Watergate contributed to the crisis of confidence that affected America throughout the 1970s.[citation needed]

Casualties

For an operation of the size and complexity of Frequent Wind, casualties were relatively light. Marine corporals McMahon and Judge killed at the DAO compound were the only KIAs of the operation and were the last US ground casualties in Vietnam[96].

A Marine AH-1J SeaCobra's engines flamed out from fuel starvation while searching for the USS Okinawa and ditched at sea. The two crew members were rescued by a boat from USS Kirk.[93] A CH-46F from the USS Hancock flown by Captain William C Nystul crashed into the sea on its approach to the ship after having flown a long and exhausting night sea and air rescue mission (SAR).[97] and First Lieutenant Michael J. Shea[98] The two enlisted crew members survived, but the bodies of the pilots were not recovered. The cause of the crash was never determined.[93]

Memorials

During the demolition of the embassy, the ladder leading from the rooftop to the helipad was removed and sent back to the United States, where it is now on display at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Museum.[99][100]

The Cessna O-1 Bird Dog that Major Buang landed on the USS Midway is now on display at the National Museum of Naval Aviation at Naval Air Station Pensacola, Florida.[101] Lady Ace 09, CH-46 serial number 154803, is now on display at the Flying Leatherneck Aviation Museum in San Diego, California[102]

The photo

On the afternoon of 29 April 1975, Hubert van Es, a Saigon-based photographer for United Press International, took the iconic photo of Operation Frequent Wind of an Air America UH-1 Huey on a rooftop picking up Vietnamese evacuees.[103][104] The building in the photo has often been identified as the US Embassy, but this is incorrect. The building was, in fact, the Pittman Apartment building at 22 Gia Long Street (now 22 Lý Tự Trọng Street), which was used as a residence by various embassy CIA and USAID employees.[105] Hubert van Es' photo is frequently used in political cartoons commenting on US foreign policy.[106][107]

-

Evacuation of CIA station personnel by Air America on April 29, 1975. Photo: Hubert van Es / UPI

In popular culture

- The stage musical, Miss Saigon, depicts events leading up to, and during Operation Frequent Wind, with the main protagonists (Chris and Kim) becoming separated as a result of the evacuation.[citation needed]

- In The Simpsons at the end of Episode 16 of Season 6, "Bart vs. Australia", the Simpsons are evacuated from the American Embassy as angry Australians gather outside in a scene reminiscent of Hubert van Es's famous photo. Homer asks the helicopter pilot if they are being taken to an aircraft carrier and is told that "the closest vessel is the USS Walter Mondale. It's a laundry ship".[108]

- In episode 11 of Hey Arnold!, Arnold learns that Mr. Hyunh was fortunate enough to have his infant daughter evacuated in Operation Frequent Wind, but without him. He later immigrated to the United States alone. Arnold tries to give Mr. Hyunh the best Christmas gift by reuniting them.[109] He succeeds by the end of the episode.

- One of the final episodes of the 1988-1991 Vietnam War TV series China Beach featured the frantic last minute attempts of the character K.C. Koloski trying to get herself and her daughter out of Saigon as it fell.[110]

References

- ^ Tobin, Thomas (1978). USAF Southeast Asia Monograph Series Volume IV Monograph 6: Last Flight from Saigon. US Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-1410205711.

- ^ Butler, David (1985). The Fall of Saigon: Scenes from the Sudden End of a Long War. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-671-46675-5.

- ^ Tobin, p. 8.

- ^ Tobin, p. 40.

- ^ Tobin, p. 9.

- ^ a b history.navy.mil (2000). "Chapter 5: The Final Curtain, 1973 - 1975". history.navy.mil. http://www.history.navy.mil/seairland/chap5.htm. Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- ^ Tobin, p. 22.

- ^ Tobin, p. 27.

- ^ a b Tobin, p. 35.

- ^ a b "Air America: Played a Crucial Part of the Emergency Helicopter Evacuation of Saigon p.1". History Net. http://www.historynet.com/air-america-played-a-crucial-part-of-the-emergency-helicopter-evacuation-of-saigon.htm. Retrieved 2011-04-29.

- ^ Tobin, p. 37.

- ^ Dunham, George R (1990). U.S. Marines in Vietnam: The Bitter End, 1973-1975 (Marine Corps Vietnam Operational Historical Series). Marine Corps Association. ISBN 978-0160264559.

- ^ a b c Dunham, p. 196.

- ^ Dunham, p. 178-179.

- ^ Tobin, p. 38.

- ^ Tobin, p. 20-21.

- ^ Tobin, p. 24.

- ^ Tobin, p. 30-31.

- ^ a b Tobin, p. 69.

- ^ a b Tobin, p. 34.

- ^ Tobin, p. 44.

- ^ Tobin, p. 46.

- ^ Tobin, p. 60.

- ^ Tobin, p. 62.

- ^ Tobin, p. 67.

- ^ Tobin, p. 66.

- ^ Tilford, Earl (1980). Search and Rescue in Southeast Asia 1961-1975. Office of Air Force History. p. 143. ISBN 9781410222640.

- ^ "USS Bausell Operation Frequent Wind". http://www.ussbausell.com/page4.html. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ^ Tobin, p. 70.

- ^ Tobin, p. 71-72.

- ^ Tobin, p. 72.

- ^ Tobin, p. 73.

- ^ Pilger, John (1975). The Last Day. Mirror Group Books. pp. 56–57. ISBN 978-0859390514.

- ^ Dunham, p. 182.

- ^ Tobin, p. 79.

- ^ Tobin, p. 80.

- ^ Tobin, p. 81.

- ^ Tobin, p. 82.

- ^ Tobin, p. 90.

- ^ Dunham, p. 183.

- ^ Tobin, p. 85-87.

- ^ "Interview with Frank Snepp, 1981." 10/14/1981. WGBH Media Library & Archives. Retrieved 3 November 2010.

- ^ Pilger, p. 63.

- ^ Dunham, p. 179-181.

- ^ a b Dunham, p. 188.

- ^ Dunham, p. 187.

- ^ Tobin, p. 98-99.

- ^ Tobin, p. 92.

- ^ Tobin, p. 99.

- ^ Snepp, Frank (1977). Decent Interval: An Insider's Account of Saigon's Indecent End Told by the CIA's Chief Strategy Analyst in Vietnam. Random House. p. 478. ISBN 0-394-40743-1.

- ^ Tanner, Stephen (2000). Epic Retreats: From 1776 to the Evacuation of Saigon. Sarpedon. p. 314. ISBN 1-885119-57-7.

- ^ Tobin, p. 111.

- ^ Tobin, p. 36.

- ^ Leeker, Dr Joe F (2009). "Air America in South Vietnam III: The Collapse". University of Texas at Dallas. http://www.utdallas.edu/library/collections/speccoll/Leeker/history/Vietnam3.pdf.

- ^ a b Leeker, p. 22.

- ^ Leeker, p. 21.

- ^ a b Leeker, p. 20.

- ^ Dunham, p. 192.

- ^ Leeker, p. 22-24.

- ^ Leeker, p. 29.

- ^ Leeker, p. 27-28.

- ^ Leeker, p. 28-29.

- ^ Leeker, p. 30.

- ^ Tobin, p. 91.

- ^ Dunham, p. 189.

- ^ Tobin, p. 97.

- ^ Dunham, p. 186.

- ^ Dunham, p. 191-192.

- ^ Dunham, p. 191.

- ^ a b Dunham, p. 195.

- ^ a b c d Dunham, p. 197.

- ^ Tobin, p. 103.

- ^ "Major James H, Kean SSN/0802 USMC, After Action Report 17 April ~ 7 May 1975 p. 3". Fallofsaigon.org. http://fallofsaigon.org/final.htm. Retrieved 2011-04-29.

- ^ Pilger, p. 27.

- ^ Pilger, p. 28.

- ^ Pilger, p. 29.

- ^ Kean, p. 5.

- ^ a b c Kean, p. 6.

- ^ Kean, p. 6-7.

- ^ Pilger, p. 30.

- ^ Dunham, p. 198.

- ^ Dunham, p. 199.

- ^ a b c Kean, p. 7.

- ^ a b c Dunham, p. 200.

- ^ Kean, p. 7-8.

- ^ Kean, p. 8.

- ^ Leeker, p. 24-25.

- ^ Tobin, p. 118.

- ^ Bowman, John S. (1985). The Vietnam War: An Almanac. Pharos Books. ISBN 0-911818-85-5. p434. (Cited at Rombough, Julia. "Frequent Wind: The Last Days of the Vietnam War". http://lark.cc.ku.edu/~lance/Family/Julia/5128text.htm. Retrieved 2006-07-01.)

- ^ Warren, JO2 Kevin F (July 1975). Naval Aviation News: Set Down to Sanctuary. Chief of Naval Operations and Naval Air Systems Command. pp. 32–33.

- ^ Tobin, p. 121.

- ^ Tobin, p. 122.

- ^ a b c Dunham, p. 201.

- ^ "Former South Korean diplomat reconciles with his Vietnamese captors". Yonhap News Agency. 11 March 2005. http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1-130156619.html.

- ^ "Interview with Gerald R. Ford, 1982.” 04/29/1982. WGBH Media Library & Archives. Retrieved 3 November 2010

- ^ Pilger, John (1975). The Last Day. Mirror Group Books. pp. 56–57. ISBN 978-0859390514.

- ^ "Capt William C Nystul". The Virtual Wall. http://thewall-usa.com/info.asp?recid=38257.

- ^ "1LT Michael J Shea". The Virtual Wall. http://thewall-usa.com/info.asp?recid=46978.

- ^ "Gerald R. Ford Presidential Museum Leadership in Diplomacy exhibit". Fordlibrarymuseum.gov. http://www.fordlibrarymuseum.gov/museum/exhibits/permanent/Shuttle-Diplomacy.asp. Retrieved 2011-04-29.

- ^ "Gerald R. Ford's Remarks at the Opening of the Ford Museum's Saigon Staircase Exhibit April 1999". Ford.utexas.edu. 1999-04-10. http://www.ford.utexas.edu/LIBRARY/SPEECHES/990410.asp. Retrieved 2011-04-29.

- ^ "OE-1 Bird Dog". http://collections.naval.aviation.museum/emuwebdoncoms/pages/doncoms/Display.php?irn=16007419&QueryPage=%2FDtlQuery.php.

- ^ "CH-46E Sea Knight "Lady Ace 09″ unveiled at aviation museum". 5 May 2010. http://www.helihub.com/2010/05/05/ch-46e-sea-knight-lady-ace-09-unveiled-at-aviation-museum/.

- ^ "Corbis Image archives: Helicopter evacuating crowd from rooftop". Corbisimages.com. 1975-04-29. http://www.corbisimages.com/Enlargement/Enlargement.aspx?id=U1835718-13&caller=search. Retrieved 2011-04-29.

- ^ Hubert van Es (2005-04-29). "Thirty Years at 300 Millimeters". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/imagepages/2005/04/29/opinion/29van_es_CA0.done.html.

- ^ Butterfield, Fox; Haskell, Kari (April 23, 2000). "Getting it wrong in a photo". New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2000/04/23/weekinreview/the-world-getting-it-wrong-in-a-photo.html?pagewanted=1. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ^ "Bremer leaves Baghdad". Le Temps. 2004-06-28. http://www.globecartoon.com/war/040628F.html.

- ^ "Exit Strategy". Politico.com. 2007-09-02. http://images.politico.com/global/edtoon-8-28-336.gif.

- ^ "[2F13 Bart vs. Australia"]. The Simpsons Archive. 2009-06-14. http://www.snpp.com/episodes/2F13.html.

- ^ "Hey Arnold! Character and Episode Guide". hey-arnold.com. 2008-06-06. http://www.hey-arnold.com/Arnold/arn_1spc.html#AC. Retrieved 2008-06-11.

- ^ "China Beach an Episode Guide". epguides.com. 2005-05-14. http://www.epguides.com/chinabeach/guide.shtml. Retrieved 2011-10-11.

Further reading

- Engelmann, Larry. Tears before the Rain: An Oral History of the Fall of South Vietnam. Oxford University Press, USA, 1990. ISBN 978-0-19-505386-9

- Snepp, Frank. Decent Interval: An Insider's Account of Saigon's Indecent End Told by the CIA's Chief Strategy Analyst in Vietnam. University Press of Kansas, 1977. ISBN 0-7006-1213-0

- Todd, Olivier. Cruel April: The Fall of Saigon. W.W. Norton & Company, 1990. ISBN 978-0-393-02787-7

External links

Categories:- 1975 in Asia

- 1975 in Vietnam

- Battles and operations of the Vietnam War

- Battles and operations of the Vietnam War in 1975

- Evacuations

- History of Ho Chi Minh City

- Military history of the United States (1900–1999)

- United States Marine Corps in the Vietnam War

- Vietnamese diaspora

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.