- Poultry farming

-

Agriculture General Agribusiness · Agricultural science

Agronomy · Animal husbandry

Extensive farming

Factory farming · Farm · Free range

Industrial agriculture

Intensive farming

Organic farming · Permaculture

Sustainable agriculture

Urban agricultureHistory History of agriculture

Arab Agricultural Revolution

British Agricultural Revolution

Green Revolution

Neolithic RevolutionTypes Aquaculture · Dairy farming

Grazing · Hydroponics

Livestock · Pig farming

Orchards · Poultry farming

Sheep husbandryCategories Agriculture

Agriculture by country

Agriculture companies

Biotechnology

Livestock

Meat industry

Poultry farming Agropedia portal

Agropedia portalPoultry farming is the practice of raising domesticated birds such as chickens, turkeys, ducks, and geese, as a subcategory of animal husbandry, for the purpose of farming meat or eggs for food.

More than 50 billion chickens are raised annually as a source of food, for both their meat and their eggs. Chickens raised for meat are called broilers, whilst those raised for eggs are called laying hens.[1] In total, the UK alone consumes over 29 million eggs per day. Some hens can produce over 300 eggs a year. Chickens will naturally live for 6 or more years. After 12 months, the hen’s productivity will start to decline. This is when most commercial laying hens are slaughtered.[2]

The majority of poultry are raised using intensive farming techniques. According to the Worldwatch Institute, 74 percent of the world's poultry meat, and 68 percent of eggs are produced this way.[3] One alternative to intensive poultry farming is free range farming.

Friction between these two main methods has led to long term issues of ethical consumerism. Opponents of intensive farming argue that it harms the environment and creates health risks, as well as abusing the animals themselves. Advocates of intensive farming say that their highly efficient systems save land and food resources due to increased productivity, stating that the animals are looked after in state-of-the-art environmentally controlled facilities.[4] A few countries have banned cage system housing, including Sweden and Switzerland. Consumers can still purchase lower cost eggs from other countries' intensive poultry farms.

Contents

Techniques

Free-range

Main article: Free rangeFree-range poultry farming consists of poultry permitted to roam freely instead of being contained in any manner. In the UK, the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs says that a free range chicken must have daytime access to open-air runs during at least half of its life. Unlike in the United States, this definition also applies to eggs. The European Union regulates marketing standards for egg farming which specifies a minimum condition for Free Range Eggs states that "hens have continuous daytime access to open-air runs, except in the case of temporary restrictions imposed by veterinary authorities".[5] In free-range broiler systems, the chickens are given continuous access to an outdoor range during the daytime and sheds where they are housed at night. Free-range chickens grow more slowly than intensive chickens. They live at least 56 days. In the EU, each chicken must have one square metre of outdoor space.[6]

Free-range poultry production requires that the poultry have access to the outside. In some cases this means the poultry are raised on pasture, enabling the poultry to move around, forage for their natural diet and live in cleaner conditions than those in batteries. In some farms, the manure from free-range poultry can be used to benefit crops.[7]

The benefits are also an increased growth rate and opportunities for natural behaviour such as pecking, scratching, foraging and exercise outdoors, as well as fresh air and daylight. Because they grow slower and have opportunities for exercise, free-range chickens have better leg and heart health and a much higher quality of life.[6]

Finding suitable land with adequate drainage to minimise worms and coccidial oocysts, suitable protection from prevailing winds, good ventilation, access and protection from predators can be difficult.[8] Excess heat, cold or damp can have a harmful effect on the animals and their productivity.[8] Unlike battery farms, free range farmers have little control over the food their animals come across, which can lead to unreliable productivity.[8]

Some free range farming in the UK, which accounts for 26% of production,[9] has also come under criticism concerning animal welfare. This is due to some large-scale free range farms where social abnormalities arise due to having large numbers of birds in an outdoor space.[9] Beak trimming due to cannibalism and infighting is common in this form of poultry farming as well as in batteries. Diseases are common and the animals are vulnerable to predators.[9] In South-East Asia, a lack of disease control in free range farming has been associated with outbreaks of Avian influenza.[10]

In organic systems, chickens are also free-range. Organic chickens are slower growing, more traditional breeds and live typically for around 81 days. They grow at half the rate of intensive chickens. They have a larger space allowance outside (at least 2 square metres and sometimes up to 10 square metres per bird).[5]

Yarding

Main article: YardingWhile often confused with free-range farming, yarding is actually a separate method of poultry culture by which chickens and cows are raised together. The distinction is that free-range poultry are either totally unfenced, or the fence is so distant that it has little influence on their freedom of movement. Yarding is common technique used by small farms in the Northeastern US.

Daily releases out of hutches or coops allows for instinctual nature for the chickens with protections from predators. The hens usually lay eggs either on the ground of the coop or in baskets if provided by the farmer. This technique can be complicated if used with roosters though, mostly because of difficulty getting them into the coop and to clean the coop while it is inside. This territorial nature is apparent while outside in which they have a brood of hens and sometimes even informal land claims. This can endanger people unaware of the existence of the territories who are attacked by the larger birds.

Intensive chicken farming

Egg-laying chickens in battery cages

Egg-laying chicken 5 days out of battery cage

Egg-laying chicken 5 days out of battery cage

In egg-producing farms, birds are typically housed in rows of battery cages. Environmental conditions are automatically controlled, including light duration, which mimics summer daylength. This stimulates the birds to continue to lay eggs all year round. Normally, significant egg production only occurs in the warmer months. Critics argue that year-round egg production stresses the birds more than normal seasonal production.

Broilers in a production house

Broilers in a production house

Meat chickens, commonly called broilers, are floor-raised on litter such as wood shavings or rice hulls, indoors in climate-controlled housing. Poultry producers routinely use nationally approved medications, such as antibiotics, in feed or drinking water, to treat disease or to prevent disease outbreaks arising from overcrowded or unsanitary conditions. In the U.S., the national organization overseeing chicken production is the Food and Drug Administration (F.D.A.). Some F.D.A.-approved medications are also approved for improved feed utilization.

In egg-producing farms, cages allow for more birds per unit area, and this allows for greater productivity and lower space and food costs, with more efforts put into egg-laying.[9] In the U.S., for example, the current recommendation by the United Egg Producers is 67 to 86 in² (430 to 560 cm²) per bird, which is about 9 inches by 9 inches. Modern poultry farming is very efficient and allows meat and eggs to be available to the consumer in all seasons at a lower cost than free range production, and the poultry have no exposure to predators.

The cage environment of egg producing does not permit birds to roam. The closeness of chickens to one another frequently causes cannibalism. Cannibalism is controlled by de-beaking (removing a portion of the bird's beak with a hot blade so the bird cannot effectively peck). However, de-beaking does not fully prevent cannibalism it just reduces the damage. Most battery chickens are missing 30-70% of plumage by the time that they are spent. Another condition that can occur in prolific egg laying breeds is osteoporosis. This is caused from year-round rather than seasonal egg production, and results in chickens whose legs cannot support them and so can no longer walk. During egg production, large amounts of calcium are transferred from bones to create eggshell. Although dietary calcium levels are adequate, absorption of dietary calcium is not always sufficient, given the intensity of production, to fully replenish bone calcium.

Under intensive farming methods, a meat chicken will live less than six weeks before slaughter. This is half the time it would take traditionally. This compares with free-range chickens which will usually be slaughtered at 8 weeks, and organic ones at around 12 weeks.[11]

In intensive broiler sheds, the air can become highly polluted with ammonia from the droppings. This can damage the chickens’ eyes and respiratory systems and can cause painful burns on their legs (called hock burns) and feet. Chickens bred for fast growth have a high rate of leg deformities because they cannot support their increased body weight. Because they cannot move easily, the chickens are not able to adjust their environment to avoid heat, cold or dirt as they would in natural conditions. The added weight and overcrowding also puts a strain on their hearts and lungs. In the U.K., up to 19 million chickens die in their sheds from heart failure each year.[12]

Indoor with higher welfare

Chickens are kept indoors but with more space (around 12 to 14 birds per square metre). They have a richer environment for example with natural light or straw bales that encourage foraging and perching. The chickens grow more slowly and live for up to two weeks longer than intensively farmed birds.[citation needed] The benefits of higher welfare indoor systems are the reduced growth rate, less crowding and more opportunities for natural behaviour.[6]

Issues with poultry farming

Humane treatment

Animal welfare groups have frequently criticized the poultry industry for engaging in practices which they believe to be inhumane. Many animal rights advocates object to killing chickens for food, the "factory farm conditions" under which they are raised, methods of transport, and slaughter. Compassion Over Killing and other groups have repeatedly conducted undercover investigations at chicken farms and slaughterhouses which they allege confirm their claims of cruelty.[13]

Conditions in intensive chicken farms may be unsanitary, allowing the proliferation of diseases such as salmonella and E. coli. Chickens may be raised in total darkness; hens are most often kept in crowded wire battery cages with space less than that of a sheet of paper per hen,[14] as opposed to cage-free or free range.[15] Rough handling and crowded transport during various weather conditions and the failure of existing stunning systems to render the birds unconscious before slaughter have also been cited as welfare concerns.

Another animal welfare concern is the use of selective breeding to create heavy, large-breasted birds, which can lead to crippling leg disorders and heart failure for some of the birds. Concerns have been raised that companies growing single varieties of birds for eggs or meat are increasing their susceptibility to disease.

A common practice among hatcheries is the culling of newly born male chicks of egg laying breeds, since they don't lay eggs, and do not grow fast enough to be profitable for meat.

Debeaking

Laying hens are routinely de-beaked when young to prevent fighting and feather pecking. Animal rights activist claim this is bad because beaks are sensitive, and the usual practice of trimming them without anaesthesia is considered inhumane by some.[16] De-beaked chickens will peck much less than chickens with beaks, which animal behaviorist Temple Grandin attributes to guarding against pain.[17] The chicken industry says that de-beaking is not painful.[18] Others argue that the procedure causes life-long chronic pain and discomfort and decreased ability to eat or drink.[16][19]

Intelligence

Some groups which advocate for more humane treatment of chickens claim that chickens are intelligent. Dr. Chris Evans of Macquarie University claims that their range of 20 calls, problem solving skills, use of representational signaling, and the ability to recognize each other by facial features demonstrate the intelligence of chickens.[20]

Antibiotics

Antibiotics have been used on poultry in large quantities since the 1940s, when it was found that the byproducts of antibiotic production, fed because the antibiotic-producing mold had a high level of vitamin B12 after the antibiotics were removed, produced higher growth than could be accounted for by the vitamin B12 alone. Eventually it was discovered that the trace amounts of antibiotics remaining in the byproducts accounted for this growth.[21]

The mechanism is apparently the adjustment of intestinal flora, favoring "good" bacteria while suppressing "bad" bacteria, and thus the goal of antibiotics as a growth promoter is the same as for probiotics. Because the antibiotics used are not absorbed by the gut, they do not put antibiotics into the meat or eggs.[22]

Antibiotics are used routinely in poultry for this reason, and also to prevent and treat disease. Many contend that this puts humans at risk as bacterial strains develop stronger and stronger resistances.[23] Critics point out that, after six decades of heavy agricultural use of antibiotics, opponents of antibiotics must still make arguments about theoretical risks, since actual examples are hard to come by. Those antibiotic-resistant strains of human diseases whose origin is known originated in hospitals rather than farms.

A proposed bill in the United States Congress would make the use of antibiotics in animal feed legal only for therapeutic (rather than preventative) use, but it has not been passed.[24] However, this may present the risk of slaughtered chickens harboring pathogenic bacteria and passing them on to humans that consume them.

In October 2000, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) discovered that two antibiotics were no longer effective in treating diseases found in factory-farmed chickens; one antibiotic was swiftly pulled from the market, but the other, Baytril, was not. Bayer, the company which produced it, contested the claim and as a result, Baytril remained in use until July 2005.[25]

To prevent any residues of antibiotics in chicken meat, any given antibiotics are required to have a "withdrawal" period before they can be slaughtered. Samples of poultry at slaughter are randomly tested by the FSIS, and shows a very low percentage of residue violations [26]

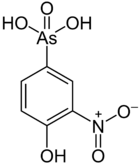

Arsenic

Chicken feed can also include Roxarsone, an antimicrobial drug that also promotes growth. Roxarsone was used as a broiler starter by about 70% of the broiler growers between 1995 to 2000.[27] The drug has generated controversy because it contains arsenic, which is highly toxic to humans. This arsenic could be transmitted through run-off from the poultry yards. A 2004 study by the U.S. magazine Consumer Reports reported "no detectable arsenic in our samples of muscle" but found "A few of our chicken-liver samples has an amount that according to EPA standards could cause neurological problems in a child who ate 2 ounces of cooked liver per week or in an adult who ate 5.5 ounces per week." The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), however, is the organization responsible for the regulation of foods in America, and all samples tested were "far less than the... amount allowed in a food product."[24]

Growth hormones

Hormone use in poultry production is illegal in the United States.[28][29] Similarly, no chicken meat for sale in Australia is fed hormones.[30] Several scientific studies have documented the fact that chickens grow rapidly because they are bred to do so, not because of growth hormones.[31][32] A small producer of natural and organic chickens confirmed this assumption:

“ If this were 1948, you might have something to worry about. Using hormones to boost egg production was a brief fad in the Forties, but was abandoned because it didn't work. Using hormones to produce soft-meated roasters was used to some extent in the Forties and Fifties, but the increased growth rates of broilers made the practice irrelevant--the broilers got as big as anyone wanted them to get when they were still young enough to be soft-meated without chemicals. The only hormone that was ever used in any quantity on poultry (DES) was banned in 1959, after everyone but a few die-hard farmers had given them up as a silly idea. Hormones are now illegal in poultry and eggs. The people who advertise "No hormones" are either woefully ignorant or are indulging in cynical fear-mongering, maybe both.[33]

” E. coli

According to Consumer Reports, "1.1 million or more Americans [are] sickened each year by undercooked, tainted chicken." A USDA study discovered E. coli in 99% of supermarket chicken, the result of chicken butchering not being a sterile process.[34] However, the same study also cautions that the type of E. coli turned up was in every case a non-lethal form distinct from the more dangerous "O157:H7" strain. Many of these chickens, furthermore, had relatively low levels of contamination.[35] Feces tend to leak from the carcass until the evisceration stage, and the evisceration stage itself gives an opportunity for the interior of the carcass to receive intestinal bacteria. (So does the skin of the carcass, but the skin presents a better barrier to bacteria and reaches higher temperatures during cooking). Before 1950, this was contained largely by not eviscerating the carcass at the time of butchering, deferring this until the time of retail sale or in the home. This gave the intestinal bacteria less opportunity to colonize the edible meat. The development of the "ready-to-cook broiler" in the 1950s added convenience while introducing risk, under the assumption that end-to-end refrigeration and thorough cooking would provide adequate protection. E. coli can be killed by proper cooking times, but there is still some risk associated with it, and its near-ubiquity in commercially farmed chicken is troubling to some. Irradiation has been proposed as a means of sterilizing chicken meat after butchering.

Avian influenza

Main article: Avian influenzaThere is also a risk that crowded conditions in chicken farms will allow avian influenza (bird flu) to spread quickly. A United Nations press release states: "Governments, local authorities and international agencies need to take a greatly increased role in combating the role of factory-farming, commerce in live poultry, and wildlife markets which provide ideal conditions for the virus to spread and mutate into a more dangerous form..."[36]

Efficiency

Farming of chickens on an industrial scale relies largely on high protein feeds derived from soybeans; in the European Union the soybean dominates the protein supply for animal feed,[37] and the poultry industry is the largest consumer of such feed.[37] Two kilograms of grain must be fed to poultry to produce 1 kg of weight gain.[38] However, for every gram of protein consumed, chickens yield only 0.33 g of edible protein.[39]

Economic factors

Changes in commodity prices for poultry feed have a direct effect on the cost of doing business in the poultry industry. For instance, a significant rise in the price of corn in the United States can put significant economic pressure on large industrial chicken farming operations.[40]

World chicken population

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations estimated that in 2002 there were nearly sixteen billion chickens in the world, counting a total population of 15,853,900,000.[41] The figures from the Global Livestock Production and Health Atlas for 2004 were as follows:

- China (3,860,000,000)

- United States (1,970,000,000)

- Indonesia (1,200,000,000)

- Brazil (1,100,000,000)

- Mexico (540,000,000)

- India (495,000,000)

- Russia (340,000,000)

- Japan (286,000,000)

- Iran (280,000,000)

- Turkey (250,000,000)

- Bangladesh (172,630,000)

- Nigeria (143,500,000)

See also

- Poultry

- Environmental issues with agriculture

- Poultry farming in the United States

- Controlled-atmosphere killing (CAK)

References

- ^ "Compassion in World Farming - Poultry". Ciwf.org.uk. http://www.ciwf.org.uk/farm_animals/poultry. Retrieved 2011-08-26.

- ^ "Compassion in World Farming - Egg laying hens". Ciwf.org.uk. http://www.ciwf.org.uk/farm_animals/poultry/egg_laying_hens/default.aspx. Retrieved 2011-08-26.

- ^ State of the World 2006 Worldwatch Institute, p. 26

- ^ Avery, Dennis. "Big Hog Farms Help the Environment," Des Moines Register, December 7, 1997, cited in Scully, Matthew. Dominion, St. Martin's Griffin, p. 30.

- ^ "European Union Regulation for marketing standards for eggs - page 25". http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CONSLEG:1991R1274:20020101:EN:PDF. Retrieved 2011-08-26.

- ^ a b c "Compassion in World Farming - Poultry - Higher welfare alternatives". Ciwf.org.uk. http://www.ciwf.org.uk/farm_animals/poultry/meat_chickens/higher_welfare_alternatives.aspx. Retrieved 2011-08-26.

- ^ Chicken feed: Grass-Fed Chickens & Pastured Poultry retrieved July 6, 2007

- ^ a b c DEFRA The welfare of hens in free range systems retrieved July 6, 2007

- ^ a b c d VEGA Laying hens, free range and bird flu retrieved July 6, 2007

- ^ WSPA International 'Free-range farming and avian flu in Asia retrieved July 6, 2007

- ^ "Compassion in World Farming - Meat chickens". Ciwf.org.uk. http://www.ciwf.org.uk/farm_animals/poultry/meat_chickens/default.aspx. Retrieved 2011-08-26.

- ^ "Compassion in World Farming - Meat chickens - Welfare issues". Ciwf.org.uk. http://www.ciwf.org.uk/farm_animals/poultry/meat_chickens/welfare_issues.aspx. Retrieved 2011-08-26.

- ^ "Undercover Investigations :: Compassion Over Killing Investigation". Kentucky Fried Cruelty. http://www.kentuckyfriedcruelty.com/u-cok.asp. Retrieved 2011-08-26.

- ^ "Animal Pragmatism: Compassion Over Killing Wants to Make the Anti-Meat Message a Little More Palatable". Washington Post. 2003-09-03. http://www.cok.net/feat/article-wp.php. Retrieved 2009-07-30.

- ^ Hernandez, Nelson (2005-10-04). "Egg Label Changed After Md. Group Complains". Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/10/03/AR2005100301593.html. Retrieved 2009-07-30.

- ^ a b Singer, Peter (2006). In Defense of Animals. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 176. ISBN 1405119411.

- ^ Grandin, Temple; Johnson, Catherine (2005). Animals in Translation. New York, NY: Scribner. p. 183. ISBN 0743247698.

- ^ Hernandez, Nelson (2005-09-19). "Advocates Challenge Humane-Care Label on Md. Eggs". Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/09/18/AR2005091801449_pf.html. Retrieved 2009-07-30.

- ^ "Md. Egg Farm Accused of Cruelty". Washington Post. 2001-06-06. http://www.isecruelty.com/article.php. Retrieved 2009-07-30.

- ^ Highfield, Roger (2006-11-15). "Telegraph.co.uk". Telegraph.co.uk. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/main.jhtml?xml=/news/2006/11/15/nhen15.xml. Retrieved 2011-08-26.

- ^ Ewing, Poultry Nutrition, 5th ed., 1963, p. 1283.

- ^ Ewing, Poultry Nutrition, 5th ed., 1963, p. 1284.

- ^ "UNL.edu". http://dwb.unl.edu/Teacher/NSF/C10/C10Links/www.sierraclub.org/cafos/toolkit/antibiotic.asp. Retrieved 2011-08-26.

- ^ a b "Chicken: Arsenic and antibiotics". ConsumerReports.org. http://www.consumerreports.org/cro/food/food-safety/animal-feed-and-food/animal-feed-and-the-food-supply-105/chicken-arsenic-and-antibiotics/index.htm?resultPageIndex=1&resultIndex=1&searchTerm=chicken%20arsenic%20and%20antibiotics. Retrieved 2009-03-24.

- ^ Baytril: FDA Bans Bayer Antibiotic for Poultry Use Randy Fabi / Reuters, July 29, 2005[dead link]

- ^ "Chicken from Farm to Table | USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service". Fsis.usda.gov. 2011-04-06. http://www.fsis.usda.gov/fact_sheets/chicken_from_farm_to_table/index.asp. Retrieved 2011-08-26.

- ^ Jones, F. T. (2007). "A Broad View of Arsenic". Poultry Science 86 (1): 2–14. PMID 17179408. http://ps.fass.org/cgi/content/abstract/86/1/2.

- ^ "The Use Of Steroid Hormones For Growth Promotion In Food-Producing Animals"[dead link]

- ^ "Chicken from Farm to Table | USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service". Fsis.usda.gov. 2011-04-06. http://www.fsis.usda.gov/fact_sheets/chicken_from_farm_to_table/index.asp#6. Retrieved 2011-08-26.

- ^ "Landline - 5/05/2002: Challenging food safety myths . Australian Broadcasting Corp". Abc.net.au. 2002-05-05. http://www.abc.net.au/landline/stories/s543233.htm. Retrieved 2011-08-26.

- ^ Havenstein GB, Ferket PR, Qureshi MA (October 2003). "Carcass composition and yield of 1957 versus 2001 broilers when fed representative 1957 and 2001 broiler diets". Poult. Sci. 82 (10): 1509–18. PMID 14601726. http://ps.fass.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=14601726.

- ^ Havenstein GB, Ferket PR, Scheideler SE, Rives DV (December 1994). "Carcass composition and yield of 1991 vs 1957 broilers when fed "typical" 1957 and 1991 broiler diets". Poult. Sci. 73 (12): 1795–804. PMID 7877935.

- ^ Robert Plamondon. "Chicken Myths and Scams". Plamondon.com. http://www.plamondon.com/faq_myths.html. Retrieved 2008-11-24.

- ^ http://www.fsis.usda.gov/OPHS/baseline/broiler1.pdf

- ^ "Revised Young Chicken Baseline" (PDF). http://www.fsis.usda.gov/PDF/Baseline_Data_Young_Chicken.pdf. Retrieved 2011-08-26.

- ^ "UN task forces battle misconceptions of avian flu, mount Indonesian campaign". UN News Center. http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=16342&Cr=bird&Cr1=flu. Retrieved 24 July 2009.

- ^ a b "Protein Sources For The Animal Feed Industry". Fao.org. 2002-05-03. http://www.fao.org/docrep/007/y5019e/y5019e03.htm#bm03. Retrieved 2011-08-26.

- ^ Lester R. Brown (2003). "Chapter 8. Raising Land Productivity: Raising protein efficiency". Plan B: Rescuing a Planet Under Stress and a Civilization in Trouble. NY: W.W. Norton & Co.. ISBN 039305859X. http://www.earthpolicy.org/Books/PB/PBch8_ss4.htm.

- ^ Tom Lovell (1998). Nutrition and feeding of fish. Springer. p. 9. ISBN 9780412077012. http://books.google.com/books?id=2nYaKaddKfkC&pg=PA9.

- ^ Jonathan Starkey (9 April 2011), "Delaware business: Chicken companies feeling pinch as corn prices soar", News Journal (Gannett): DelawareOnline, OCLC 38962480, http://www.delawareonline.com/article/20110410/BUSINESS/104100342/-1/NLETTER01/Chicken-companies-feeling-pinch-as-corn-prices-soar, retrieved 10 April 2011

- ^ "Chicken population". Fao.org. http://www.fao.org/docrep/004/ad452e/ad452e30.htm#TopOfPage. Retrieved 2011-08-26.

Categories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.