- Double entendre

-

A double entendre (French pronunciation: [dublɑ̃tɑ̃dʁə]) or adianoeta[1] is a figure of speech in which a spoken phrase is devised to be understood in either of two ways. Often the first (more obvious) meaning is straightforward, while the second meaning is less so: often risqué or ironic.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines a double entendre as especially being used to "convey an indelicate meaning". It is often used to express potentially offensive opinions without the risks of explicitly doing so.

A double entendre may exploit puns to convey the second meaning. Double entendres tend to rely more on multiple meanings of words, or different interpretations of the same primary meaning; they often exploit ambiguity and may be used to introduce it deliberately in a text. Sometimes using a homophone (i.e. a different spelling that yields the same pronunciation) can sometimes be used as a pun as well as a "double entendre" of the subject.

Contents

Structure

A person who is unfamiliar with the hidden or alternative meaning of a sentence may fail to detect its innuendos, aside from observing that others find it humorous for no apparent reason. Perhaps because it is not offensive to those who do not recognize it, innuendo is often used in sitcoms and other comedy considered suitable for children, who may enjoy the comedy while being oblivious to its second meanings. For example, Shakespeare's play Much Ado About Nothing used this ploy to present a surface level description of the play as well as a pun on the Elizabethan use of "nothing" as slang for vagina.[2]

A triple entendre is a phrase that can be understood in any of three ways, such as in the cover of the 1981 Rush album Moving Pictures. The left side of the front cover shows a moving company who are carrying paintings out of a building. On the right side, people are shown crying because the pictures carried by the movers are emotionally "moving". Finally, the back cover features a film crew making a "moving picture" of the whole scene.[3] Another example can be observed in the 1995 film GoldenEye, in which the female villain is crushed to death between a tree, to which James Bond quips, "She always did enjoy a good squeeze." This references her death, her method of executing men (crushing them with her legs) and her sexual appetite.[4] Another example is a sports bar at the bottom of 5th street in Benicia, California, named "Bottom of the Fifth", referring to (1) the address, (2) a period in baseball, and (3) a measure of consumption of a common quantity of alcoholic beverage.

In contrast, comedian Benny Hill, whose television shows included straightforward sexual gags, has been jokingly called "the master of the single entendre".[5]

Etymology

The expression comes from French double = "double" and entendre = "to hear". However, the English formulation is a corruption of the authentic French expression double entente[citation needed] and modern French uses double sens instead.

The term "adianoeta" comes from Greek ἀδιανόητα and means "unintelligible".[6]

Usage

Literature

The title of Damon Knight's story To Serve Man is a double entendre, it can mean "to perform a service for humanity" or "to serve a human as food". An alien cookbook with the title To Serve Man is featured in the story, implying that the aliens eat humans.

Examples of sexual innuendo and double-entendre occur in Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales (14th century), in which the Wife of Bath's Tale is laden with double entendres. The most famous of these may be her use of the word "queynte" to describe both domestic duties (from the homonym "quaint") and genitalia ("queynte" being a root of the modern English word cunt.)

The title of Sir Thomas More's 1516 fictional work Utopia is a double entendre because of the pun between two Greek-derived words that would have identical pronunciation: with his spelling, it means "no place"[7] (as echoed later in Samuel Butler's later Erewhon); spelled as the rare word Eutopia, it is pronounced the same[8] by English-speaking readers, but has the meaning "good place".

The poem Ozymandias by Percy Shelley published in 1818, is an example of ironic double entendre. Looking upon the shattered ruins of a colossus, the traveler reads:

My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!The speaker believes that the king's sole intended meaning of "despair" was that nobody could hope to equal his achievements, but the traveler seems to find another meaning—that the reader might "despair" to find that all beings are mortal, that king and peasant alike inevitably share oblivion in the sands of time.[9] This portrayal of an unintended double entendre exemplifies a case of the double entendre as the poet's figure of speech.

In Homer's "The Odyssey", when Odysseus is captured by the Cyclops Polyphemus, he tells the Cyclops that his name is No-man. When Odysseus attacks the Cyclops later that night and stabs him in the eye, the Cyclops runs out of his cave, yelling to the other cyclopes that "No-man has hurt me!", which leads the other cyclopes to take no action, allowing Odysseus and his men to escape.

Often, older media contain words or phrases that were innocuous at the time of publication, but have a more obscene or sexual meaning today, such as "have a gay old time" from The Flintstones ("gay" means "happy" in this context). One possibly intentional example is the character Charley Bates from Charles Dickens' Oliver Twist, frequently referred to as Master Bates. The word "masturbate" was in use when the book was written.

Stage performances

Shakespeare frequently used innuendos in his plays. Indeed, Sir Toby in Twelfth Night is seen saying, in reference to Sir Andrew's hair, that "it hangs like flax on a distaff; and I hope to see a housewife take thee between her legs and spin it off;" the Nurse in Romeo and Juliet says that her husband had told Juliet when she was learning to walk that "Yea, dost thou fall upon thy face? Thou wilt fall backward when thou hast more wit;", or is told the time by Mercutio: "for the bawdy hand of the dial is now upon the prick of noon"; and in Hamlet, Hamlet torments Ophelia with a series of sexual puns, viz. "country" (similar to "cunt").

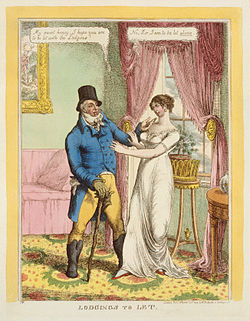

In the UK, starting in the 19th century, Victorian morality disallowed innuendo in the theatre as being unpleasant, particularly for the ladies in the audience. In music hall songs, on the other hand, innuendo remained very popular. Marie Lloyd's song 'She Sits Among The Cabbages And Peas' is an example of this. (Music hall in this context is to be compared with Variety, the one common, low-class and vulgar; the other demi-monde, worldly and sometimes chic.) In the 20th century there began to be a bit of a crackdown on lewdness, including some prosecutions. It was the job of the Lord Chamberlain to examine the scripts of all plays for indecency. Nevertheless, some comedians still continued to get away with it. Max Miller, famously, had two books of jokes, a white book and a blue book, and would ask his audience which book they wanted to hear stories from. If they chose the blue book, it was their own choice and he could feel reasonably secure he was not offending anyone.

Radio and television

In Britain, innuendo humour did not transfer to radio or cinema at first, but eventually and progressively it began to filter through from the late 1950s and 1960s on. Particularly significant in this respect were the Carry On series of films and the BBC radio series Round the Horne, although this humor is carried because of the apparent "nonsense" language that the protagonists use but in fact are having a "rude" conversation in Polari (gay slang). Spike Milligan, writer of The Goon Show, remarked that a lot of blue innuendo came from serviceman's jokes, which most of the cast understood (they all had been soldiers) and many of the audience understood, but which passed over the heads of most of the BBC producers and directors, most of whom were "Officer class."

In 1968, the office of the Lord Chamberlain ceased to have responsibility for censoring live entertainment, after the Theatres Act 1968. By the 1970s innuendo had become widely pervasive across much of the British media, including sitcoms and radio comedy, such as I'm Sorry I Haven't a Clue and Round the Horne. For example, in the 1970s series Are You Being Served?, Mrs. Slocombe frequently referred to her pet cat as her "pussy", apparently unaware of how easily her statement could be misinterpreted, such as "It's a wonder I'm here at all, you know. My pussy got soakin' wet. I had to dry it out in front of the fire before I left." Someone unfamiliar with sexual slang might find this statement funny simply because of the references to her cat, whereas generally a viewer would be expected to detect the innuendo ("pussy" is sexual slang for vulva).

Modern U.S. comedies like The Office do not hide the fact of adding sexual innuendos into the script. One repeated example comes from main character Michael Scott who often deploys the catch-phrase "that's what she said" after another character's innocent statement, to turn it retroactively into a sexual pun.

Movies

Bawdy double entendres, such as "I'm the kinda girl who works for Paramount by day, and Fox all night", and "I feel like a million tonight—but only one at a time", were the trademark of Mae West, in her early-career vaudeville performances as well as in her later plays and movies.

Double entendres are popular in modern movies, as a way to conceal adult humour in a work aimed at general audiences. The James Bond films are rife with such humour. For example, in Tomorrow Never Dies (1997), when Bond is disturbed by the telephone while in bed with a Danish girl, he explains to Moneypenny that he is busy "brushing up on a little Danish". Moneypenny responds in kind by pointing out that Bond was known as "a cunning linguist", a play on the word "cunnilingus". More obvious examples include Pussy Galore in Goldfinger and Holly Goodhead in Moonraker. The double entendres of the Bond films were parodied in the Austin Powers series.

Music

Double entendres are very common in the titles and lyrics of pop songs, such as "If I Said You Had a Beautiful Body Would You Hold It Against Me" by The Bellamy Brothers, which is based on an old Groucho Marx quote, where the person being talked to is asked, by one interpretation if they would be offended, and by the other, if they would press their body against the person doing the talking.

Singer and songwriter Bob Dylan, in his somewhat controversial song "Rainy Day Women #12 & 35", repeats the line "Everybody must get stoned." In context, the phrase refers to the punishment of stoning, as described in the Bible, but on another level it means to get stoned with narcotics. AC/DC's hit Big Balls off their album Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap refers to ballroom dancing, but the lyrics suggest masturbation of the testicles.

Another notable example is the Britney Spears song, "If You Seek Amy" which could be taken two ways. In the music video, she appears to be looking for a girl named Amy in a club, but the lyrics can be interpreted phonetically as "All of the boys and all of the girls are begging to F-U-C-K me."

During the 1940s, Benny Bell recorded several "party records" that contained double entendre including "Everybody Wants My Fanny" where the lyrics state "Everybody wants to seize my fanny, everybody likes to squeeze my fanny, they do everything to please my fanny, still she loves no one but me", where "Fanny" could be either a girl's name or a slang for someone's backside.

Comics and pictoral

The Finbarr Saunders strip in the British comic Viz is built around double entendres. It is one of Viz's longest running strips, often titled 'Finbarr Saunders and his Double Entendres'.

Donald McGill was the creator of many cartoon seaside postcards which used innuendo. The Blues Blues songs are noted for double entendre. When Bessie Smith sings: "Put a little sugar in my bowl" there is a definite sexual allusion. Another blues standard is a reference to thoroughbred racing. "My daddy was no jockey but he sure knowed how to ride. Jes git in the middle and sway from side to side." Or a 1980s blues song with the lines: "Granpa can't fly his kite because grandma won't give him no tail."

Social interaction

Double entendres often arise in the replies given to inquiries. For example, the response to the question "What is the difference between ignorance and apathy?" would be "I don't know and I don't care". The dual meaning arises in the iteration (though from a first-person perspective) of the definitions of both terms within the reply ("I don't know" defining ignorance, and "I don't care" defining apathy). In the more obvious sense, the reply may simply indicate that the replier neither knows nor cares about what the difference is between the two words.

Another instance of double entendre involves responding to a seemingly innocuous sentence that could have a sexual meaning with the phrase "that's what she said". An example might be if one were to say "It's too big to fit in my mouth" upon being served a large sandwich, someone else could say "That's what she said," as if the statement were a reference to oral sex. This phrase was used in the "Wayne's World" Saturday Night Live skits, and was a recurring joke on the US sitcom The Office. The phrase "...as the actress said to the bishop" is used in a similar way. The African American musical idiom known as the blues often employs double entendre. The first meaning is usually rather prosaic while the second meaning is risque. For example, Bessie Smith sang: "I want a little sugar in my bowl." It is clear that on one level she is referring to a sugar bowl, but the second or hidden meaning refers to her female genitalia; the sugar is a man's semen. Another blues double entendre refers to thoroughbred racing. "My daddy was no jockey oh but he could ride/My daddy was no jockey but sho' could ride. He said jes git in the middle and sway from side to side." Finally, a more recent blues song (circa the 1980s) contained the double entendre: "Granpa can't fly his kite because grandma won't give him no tail."

See also

- Albur

- Coincidence

- Doublespeak

- Euphemism

- Paraprosdokian

- Pun

- Spoonerism

- Said the actress to the bishop (also That's what she said)

- Word play

- The Blues

References

- ^ definition of Adianoeta at rhetoric.byu.edu. Accessed on 2009-08-06

- ^ "Taglines Galore". http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Much_Ado_About_Nothing#Noting. Retrieved 2011-04-28.

- ^ http://www.nimitz.net/rush/faq2ans.html#82

- ^ http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0113189/quotes?qt=qt0448546

- ^ "Taglines Galore". http://www.taglinesgalore.com/tags/b.html. Retrieved November 2008.

- ^ definition of Adianoeta at ww.odlt.org. Accessed on 2009-08-06

- ^ Merriam-Webster's Online Search

- ^ A. D. Cousins, Macquarie University. "Utopia." The Literary Encyclopedia. 25 Oct. 2004. The Literary Dictionary Company. 3 January 2008.

- ^ Or the irony that this monarch assets his claim to majesty and awe yet his "works" are in ruin: "Nothing beside remains: round the decay/ Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare."

Categories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.