- Ozymandias

-

This article is about Shelley's poem. For other uses, see Ozymandias (disambiguation).OZYMANDIAS

I met a traveller from an antique land

Who said: Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desart. Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them and the heart that fed:

And on the pedestal these words appear:

"My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!"

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.[1]"Ozymandias" (

/ˌɒziˈmændiəs/,[2] also pronounced with four syllables in order to fit the poem's meter) is a sonnet by Percy Bysshe Shelley, published in 1818 (see 1818 in poetry) in the January 11 issue of The Examiner in London. It is frequently anthologised and is probably Shelley's most famous short poem. It was written in competition with his friend Horace Smith, who wrote another sonnet entitled "Ozymandias" seen below.

/ˌɒziˈmændiəs/,[2] also pronounced with four syllables in order to fit the poem's meter) is a sonnet by Percy Bysshe Shelley, published in 1818 (see 1818 in poetry) in the January 11 issue of The Examiner in London. It is frequently anthologised and is probably Shelley's most famous short poem. It was written in competition with his friend Horace Smith, who wrote another sonnet entitled "Ozymandias" seen below.In addition to the power of its themes and imagery, the poem is notable for its virtuosic diction. The rhyme scheme of the sonnet is unusual[3] and creates a sinuous and interwoven effect.

Contents

Analysis

1817 draft by Percy Bysshe Shelley, Bodleian Library

1817 draft by Percy Bysshe Shelley, Bodleian Library

The central theme of "Ozymandias" is the inevitable complete decline of all leaders, and of the empires they build, however mighty in their own time.[4]

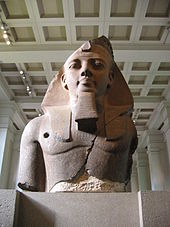

Ozymandias was another name for Ramesses the Great, Pharaoh of the nineteenth dynasty of ancient Egypt.[5] Ozymandias represents a transliteration into Greek of a part of Ramesses' throne name, User-maat-re Setep-en-re. The sonnet paraphrases the inscription on the base of the statue, given by Diodorus Siculus in his Bibliotheca historica, as "King of Kings am I, Osymandias. If anyone would know how great I am and where I lie, let him surpass one of my works."[6][7]

Shelley's poem is often said to have been inspired by the arrival in London of a colossal statue of Ramesses II, acquired for the British Museum by the Italian adventurer Giovanni Belzoni in 1816.[8] Rodenbeck and Chaney, however,[9] point out that the poem was written and published before the statue arrived in Britain, and thus that Shelley could not have seen it. Its repute in Western Europe preceded its actual arrival in Britain (Napoleon had previously made an unsuccessful attempt to acquire it for France, for example), and thus it may have been its repute or news of its imminent arrival rather than seeing the statue itself which provided the inspiration.

The 2008 edition of the travel guide Lonely Planet's guide to Egypt says that the poem was inspired by the fallen statue of Ramesses II at the Ramesseum, a memorial temple built by Ramesses at Thebes, near Luxor in Upper Egypt.[10] This statue, however, does not have "two vast and trunkless legs of stone", nor does it have a "shattered visage" with a "frown / And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command." Nor does the base of the statue at Thebes have any inscription, although Ramesses's cartouche is inscribed on the statue itself.

Among the earlier senses of the verb "to mock" is "to fashion an imitation of reality" (as in "a mock-up"),[11] but by Shelley's day the current sense "to ridicule" (especially by mimicking) had come to the fore.

This sonnet is often incorrectly quoted or reproduced.[12] The most common misquotation – "Look upon my works, ye Mighty, and despair!" – replaces the correct "on" with "upon", thus turning the regular decasyllabic (iambic pentameter) verse into an 11-syllable line.[13]

Publication history

Both Percy Bysshe Shelley and Horace Smith submitted a sonnet on the subject to The Examiner published by Leigh Hunt in London. Shelley's was published on January 11, 1818 under the pen name Glirastes, appearing on page 24 under Original Poetry. Smith's was published on February 1, 1818 with the initials H.S. Shelley's poem was later republished under the title "Sonnet. Ozymandias" in his 1819 collection Rosalind and Helen, A Modern Eclogue; with Other Poems by Charles and James Ollier and in the 1826 Miscellaneous and Posthumous Poems of Percy Bysshe Shelley by William Benbow, both in London. The poem also appeared in The Complete Works of Percy Bysshe Shelley, edited by Roger Ingpen and Walter E. Peck, published in New York by Gordian Press, 1965, a collection first published in 1904 in London and Boston by Virtue and Company.

Smith's poem

IN Egypt's sandy silence, all alone,

Stands a gigantic Leg, which far off throws

The only shadow that the Desart knows:—

"I am great OZYMANDIAS," saith the stone,

"The King of Kings; this mighty City shows

"The wonders of my hand."— The City's gone,—

Nought but the Leg remaining to disclose

The site of this forgotten Babylon.

We wonder,—and some Hunter may express

Wonder like ours, when thro' the wilderness

Where London stood, holding the Wolf in chace,

He meets some fragment huge, and stops to guess

What powerful but unrecorded race

Once dwelt in that annihilated place.—Horace Smith.[14]Percy Bysshe Shelley wrote this poem in competition with his friend Horace Smith, who published his sonnet a month after Shelley's in the same magazine.[15] It takes the same subject, tells the same story, and makes a similar moral point, but one related more directly to modernity, ending by imagining a hunter of the future looking in wonder on the ruins of an annihilated London. It was originally published under the same title as Shelley's verse; but in later collections Smith retitled it "On A Stupendous Leg of Granite, Discovered Standing by Itself in the Deserts of Egypt, with the Inscription Inserted Below".[16]

Musical settings

Edward Elgar started on a setting but never finished it. The best known setting appears to be that in Russian for baritone by the Ukrainian composer Borys Lyatoshynsky.

In popular culture

- Terry Carr's science fiction short story Ozymandias was inspired by the poem.

- In John Christopher's science fiction "Tripods" trilogy, Ozymandias is one of the rebels who recruits children to fight the extraterrestrial "Tripods".

- Ozymandias (real name Adrian Veidt) is a character in the comic book limited series Watchmen. The inscription in Shelley's poem forms the epigraph to the penultimate issue of the series.

- In Marvel Comics, Ozymandias is a former Egyptian warlord, turned into immortal living stone, who was the slave and chronicler of the villain Apocalypse.

- Jefferson Starship's 1976 album Spitfire starts its second side with "Song to the Sun: Part I: Ozymandias / Part II: Don't Let It Rain".

- The Sisters of Mercy recorded a song called "Ozymandias", which featured as a B-side on the 12-inch single of "Dominion/Mother Russia". The lyrics of "Dominion" include the final line of Shelley's poem.

- The album Rattus Norvegicus by The Stranglers mentions Ozymandias in the track "Ugly".

- The B-side of Jean-Jacques Burnel's 1979 7" single Freddie Laker (Concorde & Eurobus) was Ozymandias, which contained a recitation of Shelley's poem.

- In Piers Anthony's book "For Love of Evil" Ozymandias is imprisoned in hell. The sonnet plays a central role to a sub-plot that has Satan recruiting Ozymandias as an administrator for Hell.

- Gatsbys American Dream has recorded a song with the title "My Name is Ozymandias".

- Fourth studio album of German neofolk band Qntal is called Ozymandias. Lyrics for the tracks Ozymandias 1 and Ozymandias 2 are taken from Shelley's poem.

- Parodied in Monty Python S4E2 Michael Ellis by Percy Bysshe Shelley reciting "Ozymandias, King of Ants"

References

- ^ Text of the poem from Shelley, Percy Bysshe (1819). Rosalind and Helen, a modern eclogue, with other poems.. London: C. and J. Ollier. OCLC 1940490. http://books.google.com/?id=Zy0PYRAv4lsC.. See also: Shelley, Percy Bysshe (1826). Miscellaneous and posthumous poems of Percy Bysshe Shelley. London: W. Benbow. OCLC 13349932. http://books.google.com/?id=MZY9AAAAYAAJ.. The two texts are identical except that in the earlier "desert" is spelled "desart".

- ^ Wells, John C. (1990). Longman pronunciation dictionary. Harlow, England: Longman. p. 508. ISBN 0582053838. entry "Ozymandias"; and OED, Third edition, March 2005; online version June 2011, accessed 22 July 2011, entry "Ozymandias, n.".

- ^ "SparkNotes: Shelley's Poetry: "Ozymandias"". SparkNotes. http://www.sparknotes.com/poetry/shelley/section2.rhtml. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- ^ MacEachen, Dougald B. CliffsNotes on Shelley's Poems. 18 July 2011.

- ^ Luxor Temple: Head of Ramses the Great

- ^ (Greek Text) Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica, 1.47.4 at the the Perseus Project

- ^ RPO Editors. "Percy Bysshe Shelley : Ozymandias". University of Toronto Department of English. University of Toronto Libraries, University of Toronto Press. http://rpo.library.utoronto.ca/poem/1904.html. Retrieved 2006-09-18.

- ^ "Colossal bust of Ramesses II, the 'Younger Memnon', British Museum. Accessed 10-01-2008

- ^ "Travelers from an antique land".; Edward Chaney, 'Egypt in England and America: The Cultural Memorials of Religion, Royalty and Revolution', in: Sites of Exchange: European Crossroads and Faultlines, eds. M. Ascari and A. Corrado (Rodopi, Amsterdam and New York,2006), 39-74.

- ^ Lonely Planet 2008 guide to Egypt, 271

- ^ OED: mock, v. "4...†b. To simulate, make a false pretense of. Obs. [citations for 1593 and 1606; both from Shakespeare]"

- ^ Reiman, Donald H; Powers, Sharon.B (1977). Shelley's Poetry and Prose. Norton. ISBN ISBN 0-393-09164-3.

- ^ For an example of this misquotation, see Postel, Sandra (1999). Pillar of sand: can the irrigation miracle last?. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0393319377. http://books.google.com/?id=QbCxGMTWWmwC. where the misquotation appears twice: at pp. xvi and 254

- ^ Ozymandias – Smith

- ^ The Examiner. Shelley's poem appeared on January 11 and Smith's on February 1.Treasury of English Sonnets. Ed. from the Original Sources with Notes and Illustrations, David M. Main

- ^ Habing, B. "Ozymandias – Smith". PotW.org. http://www.potw.org/archive/potw192.html. Retrieved 2006-09-23. "The iambic pentameter contains five 'feet' in a line. This gives the poem rhythm and pulse, and sometimes is the cause of rhyme."

Further reading

- Reiman, Donald H. and Sharon B. Powers. Shelley's Poetry and Prose. Norton, 1977. ISBN 0-393-09164-3.

- Shelley, Percy Bysshe and Theo Gayer-Anderson (illust.) Ozymandias. Hoopoe Books, 1999. ISBN 977-5325-82-X

- Rodenbeck, John. “Travelers from an Antique Land: Shelley's Inspiration for ‘Ozymandias,’” Alif: Journal of Comparative Poetics, no. 24 (“Archeology of Literature: Tracing the Old in the New”), 2004, pp. 121–148.

- Edward Chaney, 'Egypt in England and America: The Cultural Memorials of Religion, Royalty and Revolution', in: Sites of Exchange: European Crossroads and Faultlines, eds. M. Ascari and A. Corrado (Rodopi, Amsterdam and New York,2006), 39-74.

- Burt, Mary E., ed. Poems Every Child Should Know: A Selection of the Best Poems of All Times for Young People. NY: Doubleday, Page and Company, 1904.

- Johnstone Parr. "Shelley's 'Ozymandias,'" Keats-Shelley Journal, Vol. VI (1957).

- Waith, Eugene M. "Ozymandias: Shelley, Horace Smith, and Denon." Keats-Shelley Journal, Vol. 44, (1995), pp. 22–28.

- Richmond, H. M. "Ozymandias and the Travelers." Keats-Shelley Journal, Vol. 11, (Winter, 1962), pp. 65–71.

- Bequette, M. K. "Shelley and Smith: Two Sonnets on Ozymandias." Keats-Shelley Journal, Vol. 26, (1977), pp. 29–31.

- Pollin, Burton R. "'Ozymandias' and the Dormouse." Dalhousie Review, 47 (1967), 361.

- Diamond, Jared M. Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed. New York: Penguin Books, 2005.

- Griffiths, J. Gwyn. "Shelley's 'Ozymandias' and Diodorus Siculus." The Modern Language Review, Vol. 43, No. 1 (January, 1948), pp. 80–84.

- Freedman, William. "Postponement and Perspectives in Shelley's 'Ozymandias'." Studies in Romanticism, Vol. 25, No. 1 (Spring, 1986), pp. 63–73.

- Thompson, D. W. "Ozymandias." PQ, XVI (1937): 59-64.

- Pottle, Frederick A. "The Meaning of Shelley's 'Glirastes'." Keats-Shelley Journal, 7, 1958.

- Edgecombe, R. S. "Displaced Christian Images in Shelley's 'Ozymandias'." Keats Shelley Review, 14 (2000), 95-99.

- Labriola, Albert C. "Sculptural Poetry: The Visual Imagination of Michelangelo, Keats, and Shelley." Comparative Literature Studies, Vol. 24, No. 4 (1987), pp. 326–334.

- Stephens, Walter. "Ozymandias: Or, Writing, Lost Libraries, and Wonder." MLN, Volume 124, Number 5, Supplement, December 2009, pp. S155-S168.

- Sng, Zachary. "The Construction of Lyric Subjectivity in Shelley's 'Ozymandias'." Studies in Romanticism, Vol. 37, No. 2 (Summer, 1998), pp. 217–233.

- Merry, Robert W. Sands of Empire: Missionary Zeal, American Foreign Policy, and the Hazards of Global Ambition. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2005. "Introduction: The Ozymandias Syndrome."

- Fagan, Brian M. The Great Warming: Climate Change and the Rise and Fall of Civilizations. New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2008.

- Geddes, Barbara. Paradigms and Sand Castles: Theory Building and Research Design in Comparative Politics. (Analytical Perspectives on Politics). Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2003.

- Volney, Constantin-François. Les ruines, ou Méditations sur les révolutions des empires (Paris: Desenne, 1791); English translation, The Ruins, or a Survey of the Revolutions of Empires (New York: Davis, 1796).

- Huang, Zhong. "A Reading of Artistic Features in Narrative Poem 'Ozymandias'." Journal of Hefei University of Technology, Hefei, China, 2005.

- Watson, Richard A. "Ozymandias, King of Kings: Postprocessual Radical Archaeology as Critique." American Antiquity, Vol. 55, No. 4 (October, 1990), pp. 673–689.

- Janowitz, A. "Shelley's Monument to Ozymandias." Philological Quarterly, Vol. 63, No. 4 (1984), pp. 477–491.

- Tom Newman's Ozymandias was recorded in 1988, the album only made it as far as test pressings before Newman's label, Oceanvoice, went out of business. Voiceprint finally released it as part of their extensive Newman reissue series in the mid-'90s

External links

- Audiorecording of "Ozymandias" by the BBC.

- LibriVox recording of "Ozymandias", selection 22, read by Leonard Wilson.

- Representative Poetry Online: Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822), "Ozymandias" (text of poem with notes)

- World Treasures (National Library of Australia) (autograph fair copy of the text from one of Shelley's notebooks; shows slight variants against modern editions)

- Horace Smith's poem of the same name, and of the same themes

- "Ozymandias" and Stanley Marsh 3

- A popular Machinima adaption of the poem by Machinima pioneers Strange Company, praised as an adaptation by film critic Roger Ebert

- "Ozymandias" an example of a modern setting of this poem.

- "Ozymandias" set to music From the 1990 concept album “Tyger and Other Tales”

- "Ozymandias" cartoon parody, Atlantea the Beautful by L. Neil Smith and Rex May, No. 48, October 25, 2009.

Categories:- Poetry by Percy Bysshe Shelley

- 1818 poems

- Ancient Egypt in fiction

- Sonnets

- Works by Percy Bysshe Shelley

- 1818 works

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.