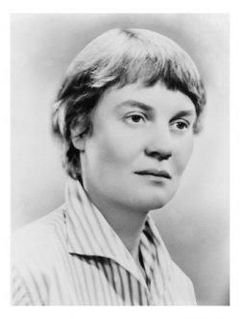

- Iris Murdoch

-

Iris Murdoch

Born 15 July 1919

Dublin, IrelandDied 8 February 1999 (aged 79)

Oxfordshire, EnglandOccupation Novelist

PhilosopherPeriod 1954–97

Dame Iris Murdoch DBE (15 July 1919 – 8 February 1999) was an Irish-born British author and philosopher, best known for her novels about political and social questions of good and evil, sexual relationships, morality, and the power of the unconscious. Her first published novel, Under the Net, was selected in 2001 by the editorial board as one of Modern Library's 100 best English-language novels of the 20th century. In 1987, she was made a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire. In 2008, The Times named Murdoch among their list of "The 50 greatest British writers since 1945".[1]

Contents

Life

Jean Iris Murdoch was born at 59 Blessington Street, Dublin, Ireland, on 15 July 1919. Her father, Wills John Hughes Murdoch, came from a mainly Presbyterian sheep farming family from Hillhall, County Down, and her mother, Irene Alice Richardson, who had trained as a singer until Iris was born, was from a middle class, Church of Ireland (Anglican) family from Dublin. When Iris was very young, her parents moved to London, where her father worked in the Civil Service.

She was educated in private progressive schools, first at the Froebel Demonstration School, and then as a boarder at the Badminton School in Bristol in 1932. She went on to read classics, ancient history, and philosophy at Somerville College, Oxford, and philosophy as a postgraduate at Newnham College, Cambridge, where she met Ludwig Wittgenstein. In 1948, she became a fellow of St Anne's College, Oxford.

She wrote her first novel, Under the Net, in 1954, having previously published essays on philosophy, and the first monograph study in English of Jean-Paul Sartre. It was at Oxford in 1956 that she met and married John Bayley, a professor of English literature and also a novelist. She went on to produce 25 more novels and other works of philosophy and drama until 1995, when she began to suffer the early effects of Alzheimer's disease, the symptoms of which she at first attributed to writer's block. She died, aged 79, in 1999, and her ashes were scattered in the garden at the Oxford Crematorium. She had no children.

Writings

Her philosophical writings were influenced by Simone Weil (from whom she borrows the concept of 'attention'), and by Plato, under whose banner she claimed to fight.[2] In re-animating Plato, she gives force to the reality of the Good, and to a sense of the moral life as a pilgrimage from illusion to reality. From this perspective, Murdoch's work offers perceptive criticism of Sartre and Wittgenstein ('early' and 'late'). Her most central parable concerns a mother-in-law 'M' who works to see her daughter-in-law 'D' "justly or lovingly"[3] and to overcome an obscuring jealousy. The parable is partly meant to show (against Oxford contemporaries including R. M. Hare and Stuart Hampshire) the importance of the 'inner' life to moral action. The parable also draws a connection between loving faith in an individual and seeing them aright. This is of significance for Murdoch's wider theory of knowledge, and for her conception of her craft as a novelist. It is the interest, for Murdoch, of St Anselm's remarks in the ontological argument, "I believe in order to understand".[4]

Her novels, in their attention and generosity to the inner lives of individuals, follow the tradition of novelists like Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, George Eliot, and Proust, besides showing an abiding love of Shakespeare. There is however great variety in her achievement, and the richly layered structure and compelling realistic imagination of The Black Prince is very different from the early comic work Under The Net or The Unicorn. The Unicorn (1963) can be read as a sophisticated Gothic romance, or as a novel with Gothic trappings, or perhaps as a parody of the Gothic mode of writing. The Black Prince (1973), for which Murdoch won the James Tait Black Memorial Prize, is a study of erotic obsession, and the text becomes more complicated, suggesting multiple interpretations, when subordinate characters contradict the narrator and the mysterious "editor" of the book in a series of afterwords. Though novels differ markedly, and her style developed, themes recur. Her novels often include upper middle class intellectual males caught in moral dilemmas, gay characters, refugees, Anglo-Catholics with crises of faith, empathetic pets, curiously "knowing" children and sometimes a powerful and almost demonic male "enchanter" who imposes his will on the other characters — a type of man Murdoch is said[5] to have modelled on her lover, the Nobel laureate Elias Canetti.

Murdoch was awarded the Booker Prize in 1978 for The Sea, the Sea, a finely detailed novel about the power of love and loss, featuring a retired stage director who is overwhelmed by jealousy when he meets his erstwhile lover after several decades apart. Several of her works have been adapted for the screen, including the British television series of her novels An Unofficial Rose and The Bell. J. B. Priestley's dramatisation of her 1961 novel A Severed Head starred Ian Holm and Richard Attenborough.

Politics

From 1938, she was, like a large proportion of her Oxford contemporaries, a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain,[6] The timing of her departure from the party seems uncertain. Conradi notes that she left twice: once technically in 1942, so she could get a job at HM Treasury, and then, at the end of that decade, leaving spiritually, as her philosophical thinking developed and she digested the lessons of Arthur Koestler's Darkness at Noon.[7] A.N. Wilson remarked that Iris Murdoch joined the Communist Party for 'religious' reasons,[8] and Conradi concurs that she left for exactly the same sort of reason.[9] She nevertheless remained close to the left for a long time.[10] She subsequently had trouble getting a visa to the United States because of her former party membership.[11] Around 1988–1990, she commented that her membership in the Communist Party had helped her see "how strong and how awful it [Marxism] is, certainly in its organized form".[11] In 1983 (two years before Neil Kinnock famously confronted Derek Hatton) she writes to Phillipa Foot that she "did not much like the Tories [...] [but] the Labour Party is [...] contaminated by the extreme left".[12] Believing that their extreme aims were "to abolish parliamentary democracy" [12] she vociferously attacked Arthur Scargill, remarking during the 1981 Miners' Strike that "they should be put up against the wall and shot."[13]

Ireland is the other sensitive detail of Murdoch' political life that seems to attract interest. Part of the interest revolves around the fact that, although Irish by both birth and traced descent on both sides, Murdoch does not display the full set of political opinions that are sometimes assumed to go with this origin: "No one ever agrees about who is entitled to lay claim to Irishness. Iris's Belfast cousins today call themselves British, not Irish... [but] with both parents brought up in Ireland, and an ancestry within Ireland both North and South going back three centuries, Iris has as valid a claim to call herself Irish as most North Americans have to call themselves American".[14] Conradi notes A.N. Wilson's record that Murdoch regretted the sympathetic portrayal of the Irish nationalist cause she had given earlier in 'The Red and the Green', and a competing defence of the book at Caen in 1978.[15] The novel while broad of sympathy is hardly an unambiguous celebration of the 1916 rising, dwelling upon bloodshed, unintended consequences and the evils of romanticism, besides celebrating selfless individuals on both sides. Iris Murdoch's father Hughes Murdoch, from Ulster, was an Officer in the British Cavalry in France at the time of the Rising. Her mother Rene Richardson was a Dubliner, and it was in Dublin that Murdoch's parents first met, while Hughes was on leave from the front.[16] Later, of Ian Paisley, Iris Murdoch stated “[he] sincerely condemns violence and did not intend to incite the Protestant terrorists. That he is emotional and angry is not surprising, after 12-15 years of murderous IRA activity. All this business is deep in my soul I’m afraid."[17]

Biographies and memoirs

Peter J. Conradi's 2001 biography was the fruit of long research and authorised access to journals and other papers. It is also a labour of love, and of a friendship with Murdoch that extended from a meeting at her Gifford Lectures to her death. The book was well received. John Updike commented: "There would be no need to complain of literary biographies [...] if they were all as good". The text addresses many popular questions about Murdoch such as how Irish she was, what her politics were. Though not a trained philosopher, Conradi's interest in Murdoch's achievement as a Thinker is evident in the biography, and yet more so in his earlier work of literary criticism The Saint and the Artist: A Study of Iris Murdoch's Works (Macmillan 1986, HarperCollins 2001). He also recalled his personal encounters with Murdoch in Going Buddhist: Panic and Emptiness, the Buddha and Me. (Short Books, 2005). Conradi's archive of material on Murdoch, together with Iris Murdoch's Oxford library, is held at Kingston University.[18]

An account of Murdoch's life with a different ambition is given by A. N. Wilson in his 2003 book Iris Murdoch as I Knew Her. The work was described by The Guardian as "mischievously revelatory" and labelled by Wilson himself as an "anti-biography".[19] It eschews Conradi's objectivity, but is careful to stress his current and past affection for his subject. Wilson's work describes a woman who was "prepared to go to bed with almost anyone" [20] and Conradi is similarly frank. A central difference is that while Murdoch's Thought is for Conradi an inspiration to his "Going Buddhist", Wilson treats Murdoch's philosophical work as at best a distraction. In a BBC Radio 4 discussion of Murdoch and her work in 2009, Wilson assented to Bidisha's view that Murdoch's philosophical output consisted of nothing but “GCSE-style” essays on Plato.,[21] and even suggested that Murdoch's later philosophical work "Metaphysics as a Guide to Morals" was a mistake that precipitated Murdoch into Alzheimers. This would be the area of difference between Wilson and Conradi. This dispute between two literary figures about the status of Murdoch's philosophical contribution has some life also among professional philosophers.The aspect of memoir in Wilson's "anti-biography" is developed in David Morgan's With Love and Rage: A Friendship with Iris Murdoch (Kingston University Press 2010). Morgan is as direct and subjective about Murdoch as is Wilson.

Murdoch was portrayed by Kate Winslet and Judi Dench in Richard Eyre's film Iris (2001), based on Bayley's memories of his wife as she developed Alzheimer's disease. Parts of the movie were filmed at Southwold in Suffolk, one of Murdoch's favourite holiday places.

Works by Iris Murdoch

Fiction

- Under the Net (1954)

- The Flight from the Enchanter (1956)

- The Sandcastle (1957)

- The Bell (1958)

- A Severed Head (1961)

- An Unofficial Rose (1962)

- The Unicorn (1963)

- The Italian Girl (1964)

- The Red and the Green (1965)

- The Time of the Angels (1966)

- The Nice and the Good (1968)

- Bruno's Dream (1969)

- A Fairly Honourable Defeat (1970)

- An Accidental Man (1971)

- The Black Prince (1973), winner of the James Tait Black Memorial Prize

- The Sacred and Profane Love Machine (1974), winner of the Whitbread Literary Award for Fiction

- A Word Child (1975)

- Henry and Cato (1976)

- The Sea, the Sea (1978), winner of the Booker Prize

- Nuns and Soldiers (1980)

- The Philosopher's Pupil (1983)

- The Good Apprentice (1985)

- The Book and the Brotherhood (1987)

- The Message to the Planet (1989)

- The Green Knight (1993)

- Jackson's Dilemma (1995)

- Something Special (Short story reprint, 1999; originally published 1957)

Philosophy

- Sartre: Romantic Rationalist (1953)

- The Sovereignty of Good (1970)

- The Fire and the Sun (1977)

- Metaphysics as a Guide to Morals. (1992) [22]

- Existentialists and Mystics: Writings on Philosophy and Literature. (1997) [23]

Plays

- A Severed Head (with J.B. Priestley, 1964)

- The Italian Girl (with James Saunders, 1969)

- The Three Arrows & The Servants and the Snow (1973)

- The Servants (1980)

- Acastos: Two Platonic Dialogues (1986)

- The Black Prince (1987)

Poetry collections

- A Year of Birds (1978; revised edition, 1984)

- Poems by Iris Murdoch (1997)

Secondary literature

- Journals - Articles on Iris Murdoch at philpapers[24]

- Antonaccio, Maria (2000) Picturing the human: the moral thought of Iris Murdoch OUP. ISBN 0-19-516660-4

- Bayley, John (1999) Elegy for Iris. Picador. ISBN 0-312-25382-6

- Bayley, John (1998 ) Iris: A Memoir of Iris Murdoch. Gerald Duckworth & Co. Ltd. ISBN 0-7156-2848-8

- Bayley, John (1999) Iris and Her Friends: A Memoir of Memory and Desire. W. W. Norton & Company ISBN 0-393-32079-0

- Conradi, P.J. (2001) Iris Murdoch: A Life. W. W. Norton & Company ISBN 0-393-04875-6

- Conradi, P.J. (forward by Bayley, John) The Saint and the Artist. Macmillan 1986, HarperCollins 2001 ISBN 0-00-712019-2

- Dooley, Gillian (ed.) and Murdoch, Iris (ed.) (2003) From a Tiny Corner in the House of Fiction: Conversations With Iris Murdoch. University of South Carolina Press ISBN 1-57003-499-0

- Laverty, Megan (2007) Iris Murdoch's Ethics: A Consideration of Her Romantic Vision. Continuum Press ISBN 0-8264-8535-9.

- Widdows, Heather (2005) "The Moral Vision of Iris Murdoch". Ashgate Press ISBN 0-7546-3625-9

- A.S. Byatt (1965) "Degrees of Freedom: The Early Novels of Iris Murdoch". Chatto & Windus

References

- ^ The 50 greatest British writers since 1945. 5 January 2008. The Times. Retrieved on 2010-02-19

- ^ Murdoch (1997) p. 16

- ^ Murdoch (1997) p. 317)

- ^ Murdoch (1992) p. 393

- ^ Conradi (2001) p. 350-352

- ^ Bove, Cheryl Browning (1993) Understanding Iris Murdoch p.3.

- ^ Conradi (2001) p 129

- ^ Spectator. 18 December 1999.

- ^ Conradi, Peter J. (2001). Iris Murdoch: A Life. W. W. Norton & Companys. p. 172.

- ^ Todd, Richard (1984) Iris Murdoch. Routledge Kegan & Paul ltd. p 15

- ^ a b Dooley and Murdoch (2003) p. 220

- ^ a b Conradi, Peter J. (2001). Iris Murdoch: A Life. W. W. Norton & Companys. p. 573.

- ^ Conradi, Peter J. (2001). Iris Murdoch: A Life. W. W. Norton & Companys. p. 572.

- ^ Conradi, Peter J. (2001). Iris Murdoch: A Life. W. W. Norton & Companys. p. 24.

- ^ Conradi, Peter J. (2001). Iris Murdoch: A Life. W. W. Norton & Companys. p. 465.

- ^ Conradi, Peter J. (2001). Iris Murdoch: A Life. W. W. Norton & Companys. p. 12.

- ^ [1]

- ^ Centre for Iris Murdoch Studies, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Kingston University, retrieved 09 04 2011.

- ^ Galen Strawson (September 6, 2003). "Telling tales". The Guardian. http://books.guardian.co.uk/reviews/biography/0,6121,1036391,00.html.

- ^ Wilson (2003)

- ^ BBC Radio 4 Archive discussion on Murdoch: An Unofficial Iris: 28/06/09

- ^ Penguin ISBN 0-14-017232-7

- ^ Penguin ISBN 0-14-026492-2

- ^ http://philpapers.org/asearch.pl?sqc=&onlineOnly=on&showCategories=on&author=Murdoch%2C%20Iris&newWindow=on&filterMode=keywords&proOnly=on&categorizerOn=&searchStr=iris%20murdoch&publishedOnly=&hideAbstracts=&filterByAreas=&sort=relevance&freeOnly=&year=&

External links

- Iris Murdoch talking to Frank Kermode in 1965 TV programme for school children.

- Jeffrey Meyers (Summer 1990). "Iris Murdoch, The Art of Fiction No. 117". The Paris Review. http://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/2313/the-art-of-fiction-no-117-iris-murdoch.

- The Iris Murdoch Building at the Dementia Services Development Centre, University of Stirling accessed 2010-02-24

- The Centre for Iris Murdoch Studies, Kingston University, London accessed 2010-02-24

- Review of Conradi's Murdoch biography, Guardian 8 September 2001 accessed 2010-02-24

- Collated reviews of Conradi biography accessed 2010-02-24

- Collated reviews of AN Wilson biography accessed 2010-02-24

- A series of Iris Murdoch walks in London accessed 2010-02-24

- Review of A. N. Wilson's Murdoch biography; The Guardian, September 6, 2003 accessed 2010-02-24

- Review of A. N. Wilson's Murdoch biography; The Guardian, September 3, 2003 accessed 2010-02-24

- Joyce Carol Oates on Iris Murdoch

- Archival material relating to Iris Murdoch listed at the UK National Register of Archives

Works by Iris Murdoch Novels: Under the Net (1954) · The Flight from the Enchanter (1956) · The Sandcastle (1957) · The Bell (1958) · A Severed Head (1961) · An Unofficial Rose (1962) · The Unicorn (1963) · The Italian Girl (1964) · The Red and the Green (1965) · The Time of the Angels (1966) · The Nice and the Good (1968) · Bruno's Dream (1969) · A Fairly Honourable Defeat (1970) · An Accidental Man (1971) · The Black Prince (1973) · The Sacred and the Profane Love Machine (1974) · A Word Child (1975) · Henry and Cato (1976) · The Sea, the Sea (1978) · Nuns and Soldiers (1980) · The Philosopher's Pupil (1983) · The Good Apprentice (1985) · The Book and the Brotherhood (1987) · The Message to the Planet (1989) · The Green Knight (1993) · Jackson's Dilemma (1995)

Short stories: "Something Special" (1957)Plays: A Severed Head (with J. B. Priestley, 1964) · The Italian Girl (with James Saunders, 1969) · The Three Arrows & the Servants and the Snow (1973) · The Servants (1980) · Acastos: Two Platonic Dialogues (1986) · The Black Prince (1987)

Poetry: A Year of Birds (1978, rev. 1984) · Poems by Iris Murdoch (1997)

Philosophy: Sartre: Romantic Rationalist (1953) · The Sovereignty of Good (1970) · The Fire and the Sun (1977) · Metaphysics as a Guide to Morals (1992) · Existentialists and Mystics (1997)

Categories:- 1919 births

- 1999 deaths

- People from Dublin (city)

- English novelists

- English dramatists and playwrights

- English poets

- English philosophers

- English women writers

- English socialists

- Women philosophers

- 20th-century philosophers

- Booker Prize winners

- Fellows of St Anne's College, Oxford

- Alumni of Somerville College, Oxford

- Alumni of Newnham College, Cambridge

- Dames Commander of the Order of the British Empire

- British people of Irish descent

- Deaths from Alzheimer's disease

- Communist Party of Great Britain members

- Old Badmintonians

- Gifford Lecturers

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.