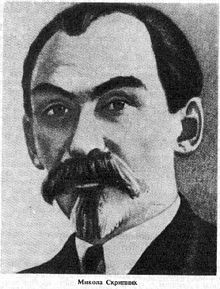

- Mykola Skrypnyk

-

Mykola Skrypnyk

Микола Олексійович Скрипник

Chairman of the People's Secretariat In office

March 4, 1918 – April 18, 1918President Yukhym Medvedev

Volodymyr Zatonsky

(chairman of Central Executive Committee)Preceded by Yevgenia Bosch (acting) Succeeded by reorganized as The Uprising Nine People's Secretary of Labor Affairs In office

March 4, 1918 – April 18, 1918Prime Minister Mykola Skrypnyk Preceded by position created Succeeded by position disbanded People's Commissar of Internal Affairs In office

July 1921 – April 1922Prime Minister Christian Rakovsky People's Commissar of Justice In office

April 1922 – 1920sPrime Minister Christian Rakovsky Preceded by Yevgeniy Terletsky Prosecutor General of Ukraine In office

January 1923 – 1920sPresident Grigory Petrovsky People's Commissar of Education In office

March 1927 – February 1933Prime Minister Vlas Chubar Head of Derzhplan UkrSSR In office

February 1933 – July 7, 1933Prime Minister Vlas Chubar Preceded by Yakym Dudnyk Succeeded by Yuriy Kotsiubynsky Personal details Born January 25, 1872

Yasynuvata, Yekaterinoslav Governorate, Russian EmpireDied July 7, 1933 (aged 61)

Kharkiv, Soviet UnionCitizenship Russia, Soviet Nationality Ukrainian Political party RSDLP(b) Alma mater Saint Petersburg State Institute of Technology Mykola Oleksiyovych Skrypnyk (Ukrainian: Микола Олексійович Скрипник, January 25 [O.S. January 13], 1872–July 7, 1933) was a Ukrainian Bolshevik leader who was a proponent of the Ukrainian Republic's independence, and led the cultural Ukrainization effort in Soviet Ukraine. When the policy was reversed and he was removed from his position, he committed suicide rather than be forced to recant his policies in a show trial. He also was the Head of the Ukrainian People's Commissariat, the post of the today's Prime-Minister.

Contents

Ukrainian independentist

Skrypnyk was born in the village Yasynuvata of Bakhmut uyezd, Yekaterinoslav Governorate, Russian Empire in family of a railway serviceman. At first he studied at the Barvinkove elementary school, then realschules of the cities Izium and Kursk. While studying at Saint Petersburg State Institute of Technology, he was arrested on political charges in 1901, prompting him to become a full-time revolutionary. Skrypnyk was eventually excluded from the Institute. He was arrested fifteen times and exiled seven times. He was convicted for the total term of 34 years and one time to the death sentence, while six times had chance to run away. In 1913 Skrypnyk was an editor of the Bolshevik's legal magazine Issues of Insurance and in 1914 was a member of the editorial collegiate of the Pravda newspaper.

After the February Revolution Skrypnyk arrived from one of his exiles to Morshansk (Tambov Governorate) to Petrograd where he was elected as a secretary of the Central Council of Factories Committees. During the October Revolution Skrypnyk was a member of the MilRevKom of the Petrograd Soviet of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies.

In December 1917, Skrypnyk was elected in absentia to the first Bolshevik government of Ukraine in Kharkiv (Respublika Rad Ukrayiny), and in March 1918 Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin appointed him its head. He replaced at that assignment Yevgenia Bogdan (Gotlieb) Bosch, daughter of a German immigrant. Skrypnyk was a leader in the so-called Kiev faction of the Ukrainian Bolsheviks, the independentists, sensitive to the issue of nationality, and promoting a separate Ukrainian Bolshevik party, while members of the predominantly Russian Katerynoslav faction preferred joining the All-Russian Communist Party in Moscow, according to Lenin's internationalist doctrine. The Kiev faction won a compromise at a conference in Taganrog, Soviet Russia in April 1918, when the Bolshevik government was dissolved and the delegates voted to form an independent Communist Party (Bolshevik) of Ukraine, CP(b)U. But in July, a Moscow congress of Ukrainian Bolsheviks rescinded the resolution, and the Ukrainian party was declared a part of the Russian Communist Party.

Skrypnyk worked for the Cheka secret police during the winter of 1918–19, then returned to Ukraine as People's Commissar of Worker-Peasant Inspection (1920–21), and Internal Affairs (1921–22).

During debates leading up to the formation of the Soviet Union in late 1922, Skrypnyk was a proponent of independent national republics, and denounced the proposal of the new General Secretary, Joseph Stalin, to absorb them into a single Russian SFSR state as thinly-disguised Russian chauvinism. Lenin temporarily swayed the decision in favour of the republics, but after his death, the Soviet Union's constitution was finalized in January 1924 with very little political autonomy for the republics. Having lost this battle, Skrypnyk and other autonomists would turn their attention towards culture.

Skrypnyk was Commissar of Justice between 1922 and 1927.

Ukrainization

Skrypnyk was appointed head of the Ukrainian Commissariat of Education in 1927.

He convinced the Central Committee of the CP(b)U, to introduce the policy of Ukrainization, encouraging Ukrainian culture and literature. He worked for this cause with almost obsessive zeal, and despite a lack of teachers and textbooks and in the face of bureaucratic resistance, achieved tremendous results during 1927–29. Ukrainian language was institutionalized in the schools and society, and literacy rates reached a very high level. As Soviet industrialization and collectivization drove the population from the countryside to urban centres, Ukrainian started to change from a peasants' tongue and the romantic obsession of a small intelligentsia, into a primary language of a modernizing society.

Skrypnyk convened an international Orthographic Conference in Kharkiv in 1927, hosting delegates from Soviet and western Ukraine (former territories of Austro-Hungarian Galicia, then part of the Second Polish Republic). The conference settled on a compromise between Soviet and Galician orthographies, and published the first standardized Ukrainian alphabet accepted in all of Ukraine. The Kharkiv orthography, or Skrypnykivka, was officially adopted in 1928.

Although he was a supporter of an autonomous Ukrainian republic and the driving force behind Ukrainization, Skrypnyk's motivation was what he saw as the best way to achieve communism in Ukraine, and he remained politically opposed to Ukrainian nationalism. He gave public testimony against "nationalist deviations" such as writer Mykola Khvylovy's literary independence movement, political anticentralism represented by former Borotbist Oleksander Shumsky, and Mykhailo Volobuev's criticism of Soviet economic policies which made Ukraine dependent on Russia.

From February to July 1933 Skrypnyk headed the Ukrainian State Planning Commission, became a member of the Politburo of the CP(b)U and served on the Executive Committee organizing the Communist International, as well as leading the CP(b)U's delegation to the Comintern.

Purged

In January 1933, Stalin sent Pavel Postyshev to Ukraine, with free rein to centralize the power of Moscow. Postyshev, with the help of thousands of officials brought from Russia, oversaw the violent reversal of Ukrainization, enforced collectivization of agriculture, including massive confiscation of grain contributing to the Great Famine or Holodomor, and conducted a purge of the CP(b)U, anticipating the wider Soviet Great Purge which was to follow in 1937.

Skrypnyk was removed as head of Education. In June, he and his "nefarious" policies were publicly discredited, and his followers condemned as "wrecking, counterrevolutionary nationalist elements". Rather than recant, on July 7 he shot himself at his desk at his apartment in Derzhprom at Dzerzhynsky Square (Dzerzhynsky Municipal Raion of Kharkiv city).

During the remainder of the 1930s, Skrypnyk's "forced Ukrainization" was reversed. Orthographic reforms were abolished and decrees were passed to bring the language steadily closer to Russian[citation needed]. The study of Russian was made obligatory and publishing of Ukrainian-language newspapers declined[citation needed]. Skrypnyk was posthumously rehabilitated only in 1990[citation needed].

See also

- People's Secretariat, the first government of the Soviet Ukraine

Preceded by

introducedDirector of All-Ukrainian Institute of Marxism–Leninism

1922–1931Succeeded by

Aleksandr ShlikhterChairman of VUTsVK First Secretary of the

Communist Party of the

Ukrainian SSR (1918–1938)Georgy Pyatakov · Serafima Hopner · Emmanuil Kviring · Stanislav Kosior · Rafail Farbman · Nikolai Nikolayev · Vyacheslav Molotov · Feliks Kon · Dmitry Manuilsky · Lazar Kaganovich · Nikita KhrushchevPeople's Secretariat / Sovnarkom Evgenia Bosh · Nikolai Skripnik · Georgy Pyatakov · Fyodor Sergeyev · Christian Rakovsky · Vlas Chubar · Panas Lyubchenko · Mikhail Bondarenko · Demian KorotchenkoInternational Representatives

(until 1923)Yuriy Kotsiubynsky (Austria) · Waldemar Aussem (Germany) · Mikhail Levitskiy (Czechoslovakia) · Mikhail Frunze (Turkey) · Mieczislaw Loganowski/Oleksandr Shumsky (Poland) · Yevgeniy Terletskiy (Baltics)References

- Chernetsky, Vitaly (2002) (PDF). The NKVD File of Mykhaylo Drai-Khmara. Kyiv: Naukova Dumka. pp. 74–75. http://www.sipa.columbia.edu/REGIONAL/HI/hi-review/vol15-i2-3-chp4.pdf#search=%22skrypnykivka%22. Includes a concise biography of Skrypnyk in annotation no. 25.

- Magocsi, Paul Robert (1996). A History of Ukraine. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-0830-5.

- Subtelny, Orest (1988). Ukraine: A History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-5808-6.

- "Mykola Skrypnyk biography" (in Ukrainian). Ukrainian government portal. http://www.kmu.gov.ua/control/uk/publish/article?art_id=1261066&cat_id=661258.

- "Mykola Skrypnyk biography" (in Ukrainian). Ukrainian encyclopedia. http://www.encyclopediaofukraine.com/display.asp?AddButton=pages\S\K\SkrypnykMykola.htm.

Categories:- 1872 births

- 1933 deaths

- People from Yasynuvata

- Old Bolsheviks

- Deaths by firearm in Ukraine

- Russian Social Democratic Labour Party members

- Politicians of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic

- Ukrainian communists

- Cheka

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.