- Nihon Shoki

-

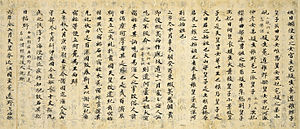

Page from a copy of the Nihon Shoki, early Heian period

Page from a copy of the Nihon Shoki, early Heian period

Shinto

This article is part of a series on ShintoPractices and beliefs Kami · Ritual purity · Polytheism · Animism · Japanese festivals · Mythology · Shinto shrines List of Shinto shrines · Twenty-Two Shrines · Modern system of ranked Shinto Shrines · Association of Shinto Shrines Notable Kami Amaterasu · Sarutahiko · Ame no Uzume · Inari · Izanagi · Izanami · Susanoo · Tsukuyomi Important literature Kojiki · Nihon Shoki · Fudoki · Rikkokushi · Shoku Nihongi · Jinnō Shōtōki · Kujiki See also Religion in Japan · Glossary of Shinto · List of Shinto divinities · Sacred objects · Japanese Buddhism · Mythical creatures

Shinto Portal

The Nihon Shoki (日本書紀), sometimes translated as The Chronicles of Japan, is the second oldest book of classical Japanese history. It is more elaborate and detailed than the Kojiki, the oldest, and has proven to be an important tool for historians and archaeologists as it includes the most complete extant historical record of ancient Japan (its beginning must be considered as largely mythological however ; its very first chapters, moreover, root in Chinese metaphysics). The Nihon Shoki was finished in 720 under the editorial supervision of Prince Toneri and with the assistance of Ō no Yasumaro.[1] The book is also called the Nihongi (日本紀 lit. Japanese Chronicles).

The Nihon Shoki begins with the creation myth (myth), explaining the origin of the world and the first seven generations of divine beings (starting with Kunitokotachi), and goes on with a number of myths as does the Kojiki, but continues its account through to events of the 8th century. It is believed to record accurately the latter reigns of Emperor Tenji, Emperor Temmu and Empress Jitō. The Nihon Shoki focuses on the merits of the virtuous rulers as well as the errors of the bad rulers. It describes episodes from mythological eras and diplomatic contacts with other countries. The Nihon Shoki was written in classical Chinese, as was common for official documents at that time. The Kojiki, on the other hand, is written in a combination of Chinese and phonetic transcription of Japanese (primarily for names and songs). The Nihon Shoki also contains numerous transliteration notes telling the reader how words were pronounced in Japanese. Collectively, the stories in this book and the Kojiki are referred to as the Kiki stories.[2]

One of the stories that first appear in the Nihon Shoki is the tale of Urashima Tarō, which has been identified as the earliest example of a story involving time travel.[3]

Contents

Chapters

The Nihon Shoki entry of 15 April 683 CE (Tenmu 12th year), mandates the use of copper coins, an early mention of Japanese currency. Excerpt of the 11th century edition.

The Nihon Shoki entry of 15 April 683 CE (Tenmu 12th year), mandates the use of copper coins, an early mention of Japanese currency. Excerpt of the 11th century edition.

- Chapter 01: (First chapter of myths) Kami no Yo no Kami no maki.

- Chapter 02: (Second chapter of myths) Kami no Yo no Shimo no maki.

- Chapter 03: (Emperor Jimmu) Kamuyamato Iwarebiko no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 04:

- (Emperor Suizei) Kamu Nunakawamimi no Sumeramikoto.

- (Emperor Annei) Shikitsuhiko Tamatemi no Sumeramikoto.

- (Emperor Itoku) Ōyamato Hikosukitomo no Sumeramikoto.

- (Emperor Kōshō) Mimatsuhiko Sukitomo no Sumeramikoto.

- (Emperor Koan) Yamato Tarashihiko Kuni Oshihito no Sumeramikoto.

- (Emperor Kōrei) Ōyamato Nekohiko Futoni no Sumeramikoto.

- (Emperor Kōgen) Ōyamato Nekohiko Kunikuru no Sumeramikoto.

- (Emperor Kaika) Wakayamato Nekohiko Ōbibi no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 05: (Emperor Sujin) Mimaki Iribiko Iniye no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 06: (Emperor Suinin) Ikume Iribiko Isachi no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 07:

- (Emperor Keiko) Ōtarashihiko Oshirowake no Sumeramikoto.

- (Emperor Seimu) Waka Tarashihiko no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 08: (Emperor Chūai) Tarashi Nakatsuhiko no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 09: (Empress Jingū) Okinaga Tarashihime no Mikoto.

- Chapter 10: (Emperor Ōjin) Homuda no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 11: (Emperor Nintoku) Ōsasagi no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 12:

- (Emperor Richū) Izahowake no Sumeramikoto.

- (Emperor Hanzei) Mitsuhawake no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 13:

- (Emperor Ingyō) Oasazuma Wakugo no Sukune no Sumeramikoto.

- (Emperor Ankō) Anaho no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 14: (Emperor Yūryaku) Ōhatsuse no Waka Takeru no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 15:

- (Emperor Seinei) Shiraka no Take Hirokuni Oshi Waka Yamato Neko no Sumeramikoto.

- (Emperor Kenzō) Woke no Sumeramikoto.

- (Emperor Ninken) Oke no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 16: (Emperor Buretsu) Ohatsuse no Waka Sasagi no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 17: (Emperor Keitai) Ōdo no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 18:

- (Emperor Ankan) Hirokuni Oshi Take Kanahi no Sumeramikoto.

- (Emperor Senka) Take Ohirokuni Oshi Tate no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 19: (Emperor Kimmei) Amekuni Oshiharaki Hironiwa no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 20: (Emperor Bidatsu) Nunakakura no Futo Tamashiki no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 21:

- (Emperor Yōmei) Tachibana no Toyohi no Sumeramikoto.

- (Emperor Sushun) Hatsusebe no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 22: (Empress Suiko) Toyomike Kashikiya Hime no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 23: (Emperor Jomei) Okinaga Tarashi Hihironuka no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 24: (Empress Kōgyoku) Ame Toyotakara Ikashi Hitarashi no Hime no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 25: (Emperor Kōtoku) Ame Yorozu Toyohi no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 26: (Empress Saimei) Ame Toyotakara Ikashi Hitarashi no Hime no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 27: (Emperor Tenji) Ame Mikoto Hirakasuwake no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 28: (Emperor Temmu, first chapter) Ama no Nunakahara Oki no Mahito no Sumeramikoto, Kami no maki.

- Chapter 29: (Emperor Temmu, second chapter) Ama no Nunakahara Oki no Mahito no Sumeramikoto, Shimo no maki.

- Chapter 30: (Empress Jitō) Takamanohara Hirono Hime no Sumeramikoto.

Process of compilation

Shoku Nihongi notes that "先是一品舍人親王奉勅修日本紀。至是功成奏上。紀卅卷系圖一卷" in the part of May, 720. It means "Up to that time, Prince Toneri had been compiling Nihongi on the orders of the emperor; he completed it, submitting 30 volumes of history and one volume of genealogy". The volume of genealogy is no longer extant.

Contributors

The process of compilation is usually studied by stylistic analysis of each chapter. Although written in classical Chinese, some sections use styles characteristic of Japanese editors, while others seem to be written by native speakers of Chinese. According to recent studies, most of the chapters after #14 (Emperor Yūryaku chronicle) were contributed by native Chinese, except for Chapters 22 and 23 (the Suiko and Jomei chronicle).[citation needed] Also, as Chapter 13 ends with the phrase "see details of the incident in the chronicle of Ōhastuse (Yūryaku) Emperor" referring to the assassination of Emperor Ankō, it is assumed that this chapter was written after the compilation of subsequent chapters. Some believe Chapter 14 was the first to be completed.

References

The Nihon Shoki is said to be based on older documents, specifically on the records that had been continuously kept in the Yamato court since the sixth century. It also includes documents and folklore submitted by clans serving the court. Prior to Nihon Shoki, there were Tennōki and Kokki compiled by Prince Shōtoku and Soga no Umako, but as they were stored in Soga's residence, they were burned at the time of the Isshi Incident.

The work's contributors refer to various sources which do not exist today. Among those sources, three Baekje documents(Kudara-ki,etc.) are cited mainly for the purpose of recording diplomatic affairs.[4]

Records possibly written in Baekje may have been the basis for the quotations in the Nihon Shoki. But textual criticism shows that scholars fleeing the destruction of the Baekje to Yamato wrote these histories and the authors of the Nihon Shoki heavily relied upon those sources.[5] This must be taken into account in relation to statements referring to old historic rivalries between the ancient Korean kingdoms of Silla, Goguryeo, and Baekje. The use of Baekje's place names in Nihon Shoki is another piece of evidence that shows the history used Baekje documents.

Some other sources are cited anonymously as aru fumi (一書; other document), in order to keep alternative records for specific incidents.

Exaggeration of reign lengths

Most scholars agree that the purported founding date of Japan (660 BCE) and the earliest emperors of Japan are legendary or mythical.[6] This does not necessarily imply that the persons referred to did not exist, merely that there is insufficient material available for further verification and study.[7]

For those monarchs, and also for the Emperors Ōjin and Nintoku, the lengths of reign are likely to have been exaggerated in order to make the origins of the imperial family sufficiently ancient to satisfy numerological expectations. It is widely believed that the epoch of 660 BCE was chosen because it is a "xīn-yǒu" year in the sexagenary cycle, which according to Taoist beliefs was an appropriate year for a revolution to take place. As Taoist theory also groups together 21 sexagenary cycles into one unit of time, it is assumed that the compilers of Nihon Shoki assigned the year 601 (a "xīn-yǒu" year in which Prince Shotoku's reformation took place) as a "modern revolution" year, and consequently recorded 660 BCE, 1260 years prior to that year, as the founding epoch.

Kesshi Hachidai ("eight undocumented monarchs")

For the eight emperors of Chapter 4, only the years of birth and reign, year of naming as Crown Prince, names of consorts, and locations of tomb are recorded. They are called the Kesshi Hachidai (欠史八代, "Eight generations lacking history") because no legends are associated with them. Recent studies support the view that these emperors were invented to push Jimmu's reign further back to the year 660 BCE. Nihon Shoki itself somewhat elevates the "tenth" emperor Sujin, recording that he was called the Hatsu-Kuni-Shirasu (御肇国: first nation-ruling) emperor.

See also

- Kokki, 620

- Tennōki, 620

- Teiki, 681

- Iki no Hakatoko no Sho, a historical record used as a reference in the compilation of Nihon Shoki

- Kojiki, 712

- Takahashi Ujibumi, ca.789

- Gukanshō, c. 1220—historical argument, Buddhist perspective

- Shaku Nihongi, 13th century—an annotated version for Nihon Shoki

- Jinnō Shōtōki. 1359—historical argument, Shinto perspective

- Nihon Ōdai Ichiran, 1652—historical argument, neo-Confucian perspective

- Tokushi Yoron, 1712—historical argument, rationalist perspective

- Historiographical Institute of the University of Tokyo

- International Research Center for Japanese Studies

- Historiography

- Philosophy of History

- William George Aston - the first translator of the Nihongi into the English language

Notes

- ^ Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697, translated from the original Chinese and Japanese by William George Aston. page xv (Introduction). Tuttle Publishing. Tra edition (July 2005). First edition published 1972. ISBN 978-0-8048-3674-6

- ^ [1]

- ^ Yorke, Christopher (February 2006), "Malchronia: Cryonics and Bionics as Primitive Weapons in the War on Time", Journal of Evolution and Technology 15 (1): 73–85, http://jetpress.org/volume15/yorke-rowe.html, retrieved 2009-08-29

- ^ Sakamoto, Tarō. (1991). The Six National Histories of Japan: Rikkokushi, John S. Brownlee, tr. pp. 40-41; Inoue Mitsusada. (1999). "The Century of Reform" in The Cambridge History of Japan, Delmer Brown, ed. Vol. I, p.170.

- ^ Sakamoto, pp. 40-41.

- ^ Rimmer, Thomas et al. (2005). The Columbia Anthology of Modern Japanese Literature, p. 555 n1.

- ^ Kelly, Charles F. "Kofun Culture," Japanese Archaeology. April 27, 2009.

References

- Brownlee, John S. (1997) Japanese historians and the national myths, 1600-1945: The Age of the Gods and Emperor Jimmu. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press. ISBN 0-7748-0644-3 Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press. ISBN 4-13-027031-1

- Brownlee, John S. (1991). Political Thought in Japanese Historical Writing: From Kojiki (712) to Tokushi Yoron (1712). Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 0-88920-997-9

- Sakamoto, Tarō. (1991). The Six National Histories of Japan: Rikkokushi, John S. Brownlee, tr. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press. 10-ISBN 0-7748-0379-7; 13-ISBN 978-0-7748-0379-3

External links

- (Japanese) Nihon Shoki TEXT (六国史全文) Downloadable lzh compressed file

- Shinto Documents Online English Translations

- Nihon Shoki Online English Translations

- Manuscript scans at Waseda University Library: [2], [3]

- University of California Berkeley, Office of Resources for International and Area Studies (ORIAS): Yamato glossary/characters

Nihon Shoki · Shoku Nihongi · Nihon Kōki · Shoku Nihon Kōki · Nihon Montoku Tennō Jitsuroku · Nihon Sandai Jitsuroku

Related Ruijū Kokushi · Honchō Seiki · Shinkokushi · Nihongiryaku

Japanese mythology Mythic texts Kojiki | Nihon Shoki | Fudoki | Kujiki | Kogo Shūi | Hotsuma Tsutae | Nihon Ryōiki | Konjaku Monogatarishū | Shintōshū

Japanese creation myth Takamagahara mythology Izumo mythology Yamata no Orochi | Hare of Inaba | ŌkuninushiHyuga mythology Human age Emperor Jimmu | Tagishimimi | Kesshi HachidaiMythical locations Major Buddhist figures Amida Nyorai | Daruma | Five Wisdom BuddhasSeven Lucky Gods Categories:- Japanese history books

- Old Japanese texts

- 8th-century history books

- Japanese mythology

- Shinto

- Nara period

- Japanese literature in Classical Chinese

- 8th-century books

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.