- Dunster Castle

-

Dunster Castle Dunster, Somerset, England

Dunster CastleShown within SomersetType Motte and bailey castle, later fortified manor house and country house Coordinates grid reference SS991434 ; Construction

materialsRed sandstone Current

ownerNational Trust Open to

the publicYes Events The Anarchy, English Civil War, the Glorious Revolution Dunster Castle is a former motte and bailey castle, now a country house, in the village of Dunster, Somerset, England. The castle lies on the top of a steep hill called the Tor, and has been fortified since the late Anglo-Saxon period. After the Norman conquest of England in the 11th century, William de Mohun constructed a timber castle on the site as part of the pacification of Somerset. A stone shell keep was built on the motte by the start of the 12th century, and the castle survived a siege during the early years of the Anarchy. At the end of the 14th century the de Mohuns sold the castle to the Luttrell family, who continued to occupy the property until the late 20th century.

The castle was expanded several times by the Luttrell family during the 17th and 18th centuries; they built a large manor house within the Lower Ward of the castle in 1617, and this was extensively modernised, first during the 1680s and then during the 1760s. The medieval castle walls were mostly destroyed following the siege of Dunster Castle at the end of the English Civil War, when Parliament ordered the defences to be slighted to prevent their further use. In the 1860s and 1870s, the architect Anthony Salvin was employed to remodel the castle to fit Victorian tastes; this work extensively changed the appearance of Dunster to make it appear more Gothic and Picturesque.

Following the death of Alexander Luttrell in 1944, the family was unable to afford the death duties on his estate. The castle and surrounding lands were sold off to a property firm, the family continuing to live in the castle as tenants. The Luttrells bought back the castle in 1954, but in 1976 Colonel Walter Luttrell gave Dunster Castle and most of its contents to the National Trust. As of 2011 the castle is operated by the trust as a tourist attraction; it is a Grade I listed building and scheduled monument.

Contents

History

11th to 12th centuries

Dunster Castle was positioned on a steep, 200-foot (61 m) high hill, sometimes called the Tor, overlooking the village of Dunster in Somerset.[1][nb 1] During the early medieval period the sea reached the base of the hill, close to the mouth of the River Avill, offering a natural defence and making the village an inland port.[3] Several Iron Age hillforts were built close to Dunster, including Bat's Castle, Black Ball Camp and Grabbist Hill, but the earliest evidence of a fortification at Dunster was an Anglo-Saxon burgh.[4] This was built on the summit of the hill and was possibly intended to protect the region against sea-borne raiders; by the mid-11th century it was controlled by a local nobleman called Aelfric.[5]

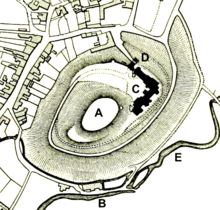

Map of Dunster Castle and immediate area: A — Motte; B – Watermill; C — Castle; D — Great Gatehouse; E River Avill

Map of Dunster Castle and immediate area: A — Motte; B – Watermill; C — Castle; D — Great Gatehouse; E River Avill

In 1066 the Normans invaded south-east England, defeating the English forces at the battle of Hastings: in the aftermath of the victory, William the Conqueror entrusted the conquest of the south-west of England to his half-brother Robert of Mortain.[6] Expecting stiff resistance, Robert marched west into Somerset, supported by forces under Walter of Douai, who entered from the north; a third force, under the command of William de Mohun, landed by sea along the Somerset coast.[7] William had been granted 68 manors in the region and by 1086 had established a castle at Dunster; this would form both the caput, or principal castle, for his new lands, and help guard the coast against the threat of any fresh sea-borne attack, as well as controlling the coastal road running from Somerset to Gloucestershire.[8] This first castle was a motte and bailey design, built upon the former Anglo-Saxon burgh; the top of the Tor was scarped to form the motte, or Upper Ward, and an area below shaped to form the bailey, or Lower Ward.[9][nb 2]

Somerset became more stable in the aftermath of the post-invasion period and the unsuccessful 1068 rebellion against Norman rule. It was common in the period for the Normans to build religious houses to accompany major castles, and accordingly William de Mohun endowed a Benedictine priory at Dunster in 1090, along with its parent abbey at Bath.[11] The River Avill was important for trade; the region around Dunster was rich with fisheries and vineyards, and Dunster Castle prospered. Stone fortifications were built on the site during the early 12th century, probably forming a shell keep around the top of the motte.[12]

In the late 1130s England began to descend into a period of civil war known as the Anarchy, during which the supporters of King Stephen fought with those of the Empress Matilda for control of the kingdom. William de Mohun's eldest son, also called William, was a noted supporter of Matilda, and Dunster was considered one of her faction's strongest castles in the south-west.[13] In 1138 forces loyal to Stephen besieged the castle; a siege castle was built nearby, but all trace of it has been lost.[14] William successfully held the castle and was made the Earl of Somerset by the grateful Empress. Chroniclers subsequently complained of the way in which he subsequently raided and controlled the region by force during the war, causing much destruction.[15] In the aftermath of the conflict, William's son, another William, inherited the castle after a short period of royal ownership under Henry II.[16] William appears to have insisted that his tenants agree to help repair and maintain the castle walls as part of their feudal service.[17]

13th to 17th centuries

The 14th-century Great Gatehouse; when first built, the Lower Ward on the right would have been at the same height as the gateway

The 14th-century Great Gatehouse; when first built, the Lower Ward on the right would have been at the same height as the gateway

In the 13th century the Lower Ward was rebuilt in stone by Reynold Mohun; this was paid for in part by Reynold commuting his tenants' ongoing duty to repair the castle walls into a single, one-off financial payment to their lord, and partially through his marriage to a rich local heiress.[18] A survey of the castle in 1266 described the Upper Ward on the top of the motte as containing a hall with a buttery, a pantry, a kitchen, a bakehouse, the chapel of Saint Stephen and a knight's hall, guarded by three towers.[19] The Lower Ward included a granary, two towers and a gatehouse; one of the towers, called the Fleming Tower, was used as a prison.[20] The castle stables lay outside the defences, further down the slope.[20] By the end of the 13th century some of the castle's roofing had been covered in lead, while other parts still used wooden shingles.[21]

In 1330 Sir John de Mohun inherited the castle; John, although a notable knight, was childless and fell into considerable debt.[22] His wife Joan took over the running of their estates, and when John died in 1376 she agreed to sell the castle to Lady Elizabeth Luttrell, the leading member of another major Norman family, for 5,000 marks, with the castle to transfer to Elizabeth on Joan's death.[23][nb 3][nb 4] At some point during this period additional stone buildings were constructed along the Lower Ward, on the side of the current mansion, and records suggest that a ditch, or moat, may have existed around the base of the Tor in the 14th century.[25]

Joan outlived Elizabeth, and in the event Sir Hugh Luttrell, who was Henry V's seneschal in Normandy, finally took over the castle on Joan's death in 1404. The castle had suffered from a lack of investment during the final years of the Mohan's ownership, and Luttrell repaired and extended the castle at a cost of £252, constructing the Great Gatehouse and a barbican between 1419 and 1424.[26][nb 5] The new entrance lay at right-angles to the old and was three storeys high, built of imported Bristol red sandstone, and contained extensive apartments; it formed a grand, if ill-defended, ceremonial route into the castle.[28] The castle was reroofed with Cornish stone tiles.[29] By the 15th century the sea had receded, and the Luttrells created a deer park for the castle at Marshwood.[30] Such a park would have been highly prestigious and allowed the Luttrell's to engage in hunting, providing the castle with a supply of venison as well as generating income.[31]

During the 15th century, England was divided by the prolonged period of civil war called the Wars of the Roses: the Luttrells were supporters of the House of Lancaster. In 1461, Sir James Luttrell died following the Lancastrian defeat at the Second Battle of St Albans, and his family were deprived of their estates by the Yorkist Edward IV.[23] The castle was given to the Herberts, but the Luttrells regained it on the accession of the Lancastarian Henry VII in 1485, when Dunster was restored to James' son, Sir Hugh Luttrell.[21] Hugh repaired the castle chapel and in the early 16th century his son, Sir Andrew Luttrell, built a new wall on the east side of the castle.[32] Andrew's son John Luttrell, who inherited the castle, was a famous soldier, diplomat, and courtier under Henry VIII and Edward VI, serving in France and in Scotland during the conflicts of the Rough Wooing.[33]

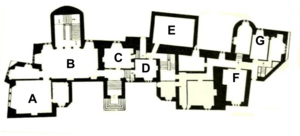

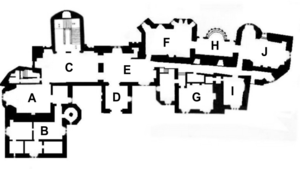

In 1542 the antiquarian John Leland reported the castle keep and buildings to be considerable disrepair, with the exception of the chapel, and by the time Sir George Luttrell inherited in 1571 the castle was dilapidated, with the family preferring to live in their house at East Quantoxhead.[34] In 1617 Sir George employed the architect William Arnold to create a new house in the Lower Ward of the castle; Arnold was an important architect in the south-west of England, and had managed the building of Montacute and Cranborne House.[35] The redesign expanded on some of the existing buildings and walls to create a 16th-century Jacobean mansion with a symmetrical front and square towers, set within the older castle walls and overlooked by the keep above.[36] The building was decorated in the latest styles, including ornamental plaster ceilings.[37] The project ran almost three times over budget, costing Luttrell more than £1,200.[35][nb 6]

English Civil War and the Restoration

In the 1640s the English Civil War broke out between the supporters of King Charles I and Parliament. Thomas Luttrell supported Parliament and after the outbreak of war William Russell, the Duke of Bedford and Parliamentary commander in Devon and Somerset, ordered him to increase the garrison at Dunster to resist a potential Royalist attack.[39] The Royalist commander William Seymour, the Duke of Somerset, attacked the castle in 1642 but was driven back by the garrison, led by Thomas' wife, Jane.[40] The war in the south-west turned in favour of the King, and on 7 June 1643 the Royalists mustered forces to attack the castle again: this time Luttrell surrendered, switching sides to support the Royalists until his death the following February.[39] Colonel Wyndham was appointed the Royalist governor of the castle.[39] The young Prince Charles, the later Charles II, stayed at the castle in May 1645.[41]

During 1645 the Royalist military cause largely collapsed, and Colonel Robert Blake led a Parliamentary force against Dunster in October.[42] In November Blake began his siege of the castle, setting up his artillery in Dunster village and starting to dig tunnels to plant mines beneath the walls.[40] The castle was briefly relieved by reinforcements in February 1646, but the siege was resumed and by April the Royalists situation was untenable – an honourable surrender was negotiated and a Parliamentary garrison installed.[42] After the end of the Second English Civil War in 1649, however, Parliament decided to deliberately destroy, or slight, the defences of castles in key Royalist areas, including the south-west.[43] In the case of Dunster, Thomas's son George Luttrell was able to convince the authorities to destroy only the medieval defensive walls, rather than the entire castle, leaving Dunster damaged from the recent siege but still habitable; the walls were demolished over 12 days in August 1650 by a team of 300 workmen.[44] The only parts of the medieval walls to survive were the Great Gatehouse and the bases of the two towers in the Lower Ward.[45]

George Luttrell died without children, and Dunster Castle passed to his brother Francis, who survived the political turmoil of both the Commonwealth years and the Restoration of Charles II to power in 1660.[46] Francis' heir, another Francis, married a wealthy heiress worth £2,500 a year (£331,000 at 2009 prices) and with this income set about modernising the castle during the 1680s, in particular building a grand staircase in the latest style.[47] Francis was a colonel in the local militia and in 1688 backed William of Orange's attempt to oust James II; when William landed in Devon, Francis mustered a number of companies of infantry at Dunster on 19 November to support him, which formed the basis for the later Green Howards regiment.[46] During this period the castle still kept an armoury of 43 muskets.[48] Francis died heavily in debt in 1690, and his widow Mary moved the contents of the castle to London, where they were destroyed in a fire in 1696.[46]

18th century

At the start of the 18th century the Luttrells and Dunster Castle faced many financial challenges.[49] Alexander, Francis's son, inherited the castle in 1704, but it was still mostly empty and carried large debts with it.[49] Alexander died young and his widow, Dorothy, spent almost twenty years paying off the debts.[49] Dorothy built a new chapel, designed by Sir James Thornhill in white Portland stone, on the rear of the mansion at a cost of £1,300 (£178,000 at 2009 prices); few records of this remain, but the interior probably resembled that of the chapel at Wimpole Hall.[50] A safer, if less grand, approach road to the castle was created, called the New Way, and the remains of the Upper Ward on top of the motte were flattened to be used as a bowling green, complete with an octagonal summer house.[51] Dorothy's son, Alexander Luttrell, took over the castle in 1726 but ran up new debts, and the castle was handed over into the control of a receiver.[49]

Henry Luttrell, who married Alexander's daughter and took the Luttrell name, moved to Dunster in 1747.[49] The couple redesigned and redecorated the castle in a Rococo style, including the extensive use of the recently invented and highly fashionable wallpaper.[52] Henry Luttrell raised the ground height of the Lower Ward between 1764 and 1765 to extend the New Way all around to the front of his mansion, adding additional ornamental towers onto the inside of the Great Gatehouse in the process.[53] A folly, Conygar Tower, was constructed by architect Richard Phelps to improve the view from the castle, and a larger park of 141 hectares (348 acres) was built just to the south of the castle, requiring the eviction of a number of tenant farmers.[54]

19th and 20th centuries

The Justice's Desk in the Justice Room[nb 7]

The Justice's Desk in the Justice Room[nb 7]

Henry's son, John, inherited the castle in 1780, but when his son, also called John, inherited in 1816 he chose to live in London instead, opening up Dunster Castle to the public.[56] By 1845 the castle appeared to visitors to be past its prime: with only two of John's sisters living there and no horses or hunting dogs left in the castle grounds, the remaining servants had little to do.[57] John's brother Henry inherited in 1857, but he too lived in London rather than at Dunster.[57]

George Luttrell inherited the castle in 1867 and began an extensive modernisation, backed by the considerable income from the Dunster estates – in a period of agricultural boom in England, the estates were producing £22,000 in revenue a year (£1.49 million at 2010 prices).[58] It was fashionable during the mid-Victorian period to remodel existing castles to produce what was felt to be a more consistent Gothic or sometimes Picturesque appearance and George, a keen historian, decided to follow this trend at Dunster; in the process, he also hoped to accommodate the larger household and facilities required for a 19th-century landowner: by 1881, the castle required 15 "living-in" servants alone.[59] He employed Anthony Salvin, a noted architect then most famous for his work at Alnwick Castle, to carry out the work between 1868 and 1872 at a total cost of £25,350 (equivalent to £1.76 million as of 2010).[60]

Salvin aimed to create a castle that would appear to have grown up organically over time, but still appeal to Victorian aesthetic taste. Accordingly, a large, square tower was built on the west side of the castle and another smaller tower on the east, both creating additional space but also making the castle deliberately asymmetrical.[61] The 18th-century chapel at the rear was demolished and replaced with another tower, alongside a modern conservatory.[62] A variety of windows in the styles of different historical periods were inserted in the walls, while modern Victorian technology, including gas lighting-supported by a gas plant in the basement-central heating and new kitchens were installed within the castle.[62] The roof of the Great Gatehouse was raised to create a more uniform sequence of battlements, and a large hall for gatherings of the local farmers installed.[63] A new wing of servants' quarters and offices were sunk into the hill, spread over two floors leading away from the main part of the mansion.[64]

Internally, Salvin knocked through existing rooms to create the Outer Hall, a new gallery on the first floor, a billiard room, a new library and a drawing room.[65] Much of the wooden 17th-century panelling in the parlour and the hall had to be stripped out as part of the renovations.[66] As part of his work, Salvin appears to have used a number of rolled wrought-iron beams to span the resulting structural gaps in the building, an advanced use of that technology for the time.[67] The house was refurnished with newly bought 16th and 17th-century artwork, two brass Italian cannons and a stuffed polar bear.[68]

Alexander Luttrell, who inherited Dunster Castle in 1910, chose to live at East Quantoxhead instead, and it was left empty until his son Geoffrey reoccupied the castle in 1920, redecorating some of the rooms in a contemporary style and building a polo ground alongside the castle.[69] The castle and the surrounding countryside at this time was very popular with the Luttrells for fox hunting and shooting.[48] During the Second World War the castle was used as a convalescent home for injured naval and American officers between 1943 and 1944.[70]

Alexander died in 1944, and the death duties proved crippling to Geoffrey. In 1949 he sold the castle and 3,480 hectares (8,600 acres) of the lands to the Ashdale Property Company, retaining a tenancy of the castle for himself.[70] The Crown Estate bought the estate from Ashdale and sold the castle back to Geoffrey in 1954.[70] His son Colonel Walter Luttrell lived away from Dunster, and following the death of his mother – the last Luttrell to live in the property – gave the castle and most of its contents to the National Trust in 1976.[70]

Today

As of 2011 Dunster Castle is operated by the National Trust as a tourist attraction. Little remains of the medieval castle except for the Great Gatehouse and the remains of several towers in the Lower Ward; the heart of the modern castle today is the much altered 17th-century manor house.[71] The key features of the castle include the original 13th-century gates and several pieces of art, including a a Tudor copy of Hans Eworth's famous allegorical portrait of Sir John Luttrell, and a sequence of leather tapestries showing scenes from the story of Antony and Cleopatra.[72] The gardens surrounding the castle cover approximately 6 hectares (15 acres) and include the National Plant Collection of Strawberry Trees; the wider parkland beyond totals 277 hectares (680 acres).[73] Just to the south of the castle is the restored 18th-century castle watermill.[74] In 2010 the castle received 128,242 visitors.[75]

Dunster Castle has been designated by English Heritage as a Grade I listed building[76] and Scheduled Ancient Monument.[77] The castle has required continuing maintenance work, in particular to its roof, itself an important historical feature. Efforts have been made to gradually redecorate the castle in a period style, using reproductions of original wallpapers and materials.[78] The National Trust installed solar panels behind the battlements on the roof in 2008 to provide electricity and make the premises more environmentally friendly. This was the first time the National Trust have taken this approach to a Grade I listed building, and it is expected to save 1,714 kg (3,778 lb) of carbon a year.[79]

See also

- List of Grade I listed buildings in West Somerset

- Castles in Great Britain and Ireland

- List of castles in England

Notes

- ^ Geologically, the hill is an outcrop of Hangman Grits, a type of red sandstone.[2]

- ^ William de Mohun also built nearby Montacute Castle in Somerset.[10]

- ^ It is impossible to accurately compare 14th-century and modern prices or incomes. For comparison, 5,000 marks equated to £3,333 in 14th century pounds and represented over three times the typical average annual income for an early 15th-century baron.[24]

- ^ Historian Oliver Garnett notes that this sale of property from one woman to another was extremely unusual for the period.[23]

- ^ It is impossible to accurately compare 14th-century and modern prices or incomes. For comparison, £252 is around a tenth of the cost of rebuilding the greater part of Hadleigh Castle in the 1360s.[27]

- ^ It is difficult to accurately compare 17th-century and modern prices or incomes. £1,200 could equate to between £171,000 to £2,140,000, depending on the measure used.[38]

- ^ The Justice Room and the Desk are named after George Luttrell's role as a Justice of the Peace.[55]

References

- ^ Mackenzie, p.54.

- ^ Dunster Castle Roof Repairs 2006–2008, (PDF) p.1, Michael Heaton Heritage Consultants, accessed 24 September 2011.

- ^ Dunning, pp.37–39; Creighton, pp.41–42.

- ^ Black Ball Camp, Arts and Humanities Data Service, accessed 28 September 2007; Univallate Hillfort, Arts and Humanities Data Service, accessed 28 September 2007; Gathercole, ClareAn archaeological assessment of Dunster (PDF) Somerset County Council accessed 1 October 2011

- ^ Mackenzie, p.54; Garnett, p.38.

- ^ Prior, pp.74–75.

- ^ Prior, p.75.

- ^ Prior, p.76; Garnett, p.38.

- ^ Prior, p.108.

- ^ Lyte (1880), p.59.

- ^ Creighton, p.187; Lyte (1880), p.60.

- ^ Prior, pp.108–109; Mackenzie, p.58; Lyte (1880), p.60; Garnett, p.5.

- ^ Lyte (1880), p.61.

- ^ Creighton, p.56; Mackenzie, p.58.

- ^ Lyte (1880), p.61; Garnett, p.38.

- ^ Lyte (1880), p.62.

- ^ Lyte (1909), p.350.

- ^ Lyte (1909), pp.349–352.

- ^ Garnett, p.30; Lyte (1909), p.353.

- ^ a b Lyte (1909), p.353.

- ^ a b Dunning, pp.37–39.

- ^ Garnett, pp.38–39.

- ^ a b c Garnett, p.39.

- ^ Pounds, p.148.

- ^ Lyte (1909), pp.354, 362.

- ^ Dunning, pp.37–39; Emery, p.677; Garnet p.39.

- ^ Alexander and Westlake, p.14.

- ^ Emery, pp.677–678; Garnett, p.30.

- ^ Garnett, p.30.

- ^ Dunster New Park, Dunster, Somerset Historic Environment Record, Somerset County Council, accessed 9 July 2011; Garnett, p.29.

- ^ Creighton, pp.190–191; Creighton and Higham, p.57.

- ^ Lyte (1909), p.364.

- ^ Phillips, pp.197, 207; Garnett, p.39.

- ^ Garnett, pp.30, 39.

- ^ a b Garnett, p.31.

- ^ Garnett, pp.5, 31; Lyte (1909), p.365.

- ^ Lyte (1909), p.365.

- ^ Five Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a UK Pound Amount, 1830 to Present, Lawrence H. Officer, MeasuringWorth, accessed 24 September 2011.

- ^ a b c Carter, p.2.

- ^ a b Garnett, p.40.

- ^ Garnett, p.45.

- ^ a b Garnett, p.40; Carter, p.3.

- ^ Thompson, p.154.

- ^ Garnett, pp.40–41; Thompson, p.156; Lyte (1909), p.367.

- ^ Carter, p.3; Garnett, p.31.

- ^ a b c Garnett, p.41.

- ^ Garnett, p.41; Lyte (1909), p.368; price ref.

- ^ a b National Trust Arts , Buildings, Collections Bulletin, February 2011, p.3, (PDF) Felicity Baber and Brian Godwin, the National Trust, accessed 24 September 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Garnett, p.42.

- ^ Garnett, pp.31, 41, Lyte (1909), p.373; Five Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a UK Pound Amount, 1830 to Present, Lawrence H. Officer, MeasuringWorth, accessed 24 September 2011.

- ^ Garnett, p.31; Lyte (1909), pp.372–373.

- ^ Garnett, p.42; Lyte (1909), p.376.

- ^ Emery, p.677; Lyte (1909), pp.378–379.

- ^ Garnett, pp.27, 29.

- ^ Garnett, p.21.

- ^ Garnett, pp.44, 48.

- ^ a b Garnett, p.44.

- ^ Garnett, p.44; Five Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a UK Pound Amount, 1830 to Present, Lawrence H. Officer, MeasuringWorth, accessed 24 September 2011.

- ^ Garnett, pp.32, 35.

- ^ Garnett, p.32; Five Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a UK Pound Amount, 1830 to Present, Lawrence H. Officer, MeasuringWorth, accessed 24 September 2011.

- ^ Garnett, pp.32–33.

- ^ a b Garnett, p.33.

- ^ Emery, p.677; Garnett, p.27.

- ^ Garnett, p.36.

- ^ Garnett, p.6, 16, 21–24.

- ^ Lyte (1909), p.382.

- ^ Dunster Castle Roof Repairs 2006–2008, p.17, (PDF) Michael Heaton Heritage Consultants, accessed 24 September 2011.

- ^ Lyte (1909), p.382; Garnett, p.6.

- ^ Garnett, pp.29, 33, 46.

- ^ a b c d Garnett, p.47.

- ^ Emery, p.677.

- ^ Garnett, pp.9, 16–17, 30.

- ^ Explore the Garden, National Trust, accessed 24 September 2011; Dunster Castle, Parks and Gardens UK, Parks and Gardens Data Services Ltd., accessed 9 July 2011.

- ^ Garnett, p.28.

- ^ Visits Made in 2010 to Visitor Attractions with ALVA, Association of Leading Visitor Attractions, accessed 9 July 2011.

- ^ "Dunster Castle and gatehouse". Images of England. English Heritage. http://www.imagesofengland.org.uk/details/default.aspx?id=264651. Retrieved 7 February 2008.

- ^ "Dunster Castle". Pastscape National Monuments Record. English Heritage. http://www.pastscape.org.uk/hob.aspx?hob_id=36863. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- ^ Dunster Castle Roof Repairs 2006–2008, (PDF) pp.4, 15, Michael Heaton Heritage Consultants, accessed 24 September 2011; Garnett, pp.21, 15.

- ^ The 1,000-year-old Castle Fighting Climate Change, Steven Morris, 7 February 2008, The Guardian, accessed 24 September 2011; Sustainable Technology Case Study, (PDF) the National Trust, accessed 24 September 2011.

Bibliography

- Alexander, Magnus and Susan Westlake. (2009) Hadleigh Castle Essex, Earthwork Analysis: Survey Report. English Heritage Research Department Report 32/2009. ISSN 17498775

- Carter, Susan. (2011) "Dunster Castle during the Civil War," Fortified England, Vol. 5 (3), pp.2–6.

- Creighton, Oliver Hamilton. (2005) Castles and Landscapes: Power, Community and Fortification in Medieval England. London: Equinox. ISBN 9781904768678.

- Creighton, Oliver Hamilton and Robert Higham. (2003) Medieval Castles. Princes Risborough, UK: Shire Publications. ISBN 9780747805465.

- Dunning, Robert. (1995) Somerset Castles. Tiverton, UK: Somerset Books. ISBN 9780861832781.

- Emery, Anthony. (2006) Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales, 1300–1500: Southern England. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521581325.

- Garnett, Oliver. (2003) Dunster Castle, Somerset.London: The National Trust. ISBN 9781843590491.

- Lyte, H. C. Maxwell. (1880) "Dunster and its Lords," The Archaeological Journal, Vol. 37, pp.57–93.

- Lyte, H. C. Maxwell. (1909) A History of Dunster and of the Families of Mohun and Luttrell, Part 2. London: St. Catherine Press. OCLC 77783795.

- Mackenzie, James D. (1896) The Castles of England: Their Story and Structure, Vol II. New York: Macmillan. OCLC 504892038.

- Pounds, Norman John Greville. (1994) The Medieval Castle in England and Wales: a social and political history. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521458283.

- Prior, Stuart. (2006) The Norman Art of War: a Few Well-Positioned Castles. Stroud, UK: Tempus. ISBN 0752436511.

- Phillips, Gervase. (1999) The Anglo-Scots Wars 1513–1550: a Military History. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 0851157467.

- Thompson, M. W. (1994) The Decline of the Castle. Leicester, UK: Harveys Books. ISBN 1854226088.

External links

Categories:- Castles in Somerset

- Historic house museums in Somerset

- Gardens in Somerset

- National Trust properties in Somerset

- Grade I listed buildings in Somerset

- Grade I listed castles

- Scheduled Ancient Monuments in Somerset

- Country houses in Somerset

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.