- Medieval deer park

-

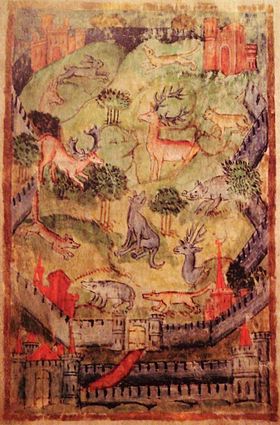

A medieval deer park was an enclosed area containing deer. It was bounded by a ditch and bank with a wooden park pale on top of the bank. The ditch was typically on the inside,[1] thus allowing deer to enter the park[citation needed] but preventing them from leaving.

Contents

History

Some deer parks were established in the Anglo-Saxon era and are mentioned in Anglo-Saxon Charters.

After the Norman conquest of England in 1066 William the Conqueror seized existing game reserves. Deer parks flourished and prolifereated under the Normans, forming a forerunner of the deer parks that became popular among England's landed gentry. The Domesday Book of 1086 records 36 of them.

Initially the Norman kings maintained an exclusive right to keep and hunt deer and established forest law for this purpose. In due course they also allowed members of the nobility and senior clergy to maintain deer parks. At their peak in the 13th century, deer parks may have covered 2% of the land area of England.[citation needed]

James I was an enthusiast for hunting but it became less fashionable and popular after the Civil War. The number of deer parks declined, but during the 18th century, many deer parks were landscaped, and the deer then became a feature of a country gentleman's park.

Deer parks are notable landscape features in their own right. However, where they have survived into the 20th century, the lack of ploughing or development has often preserved other features within the park[2], including barrows, Roman roads and abandoned villages.

Status

To establish a deer park a Royal licence was required — especially if the park was in or near a royal forest. Because of their cost and exclusivity, deer parks became status symbols. Since deer were almost all kept within exclusive hunting reserves used as aristocratic playgrounds, there was no legitimate market for venison.[3] Thus the ability to eat venison or give it to others was also a status symbol. Consequently, many deer parks were maintained for the supply of venison, rather than hunting the deer.

Form

The landscape within a deer park was manipulated to produce a habitat that was both suitable for the deer and also provided space for hunting. "Tree dotted lawns, tree clumps and compact woods" [4] provided "launds" (pasture)[5] over which the deer were hunted and wooded cover for the deer to avoid human contact. The landscape was intended to be visually attractive as well as functional.

Identifying former deer parks

W. G. Hoskins remarked that "the reconstruction of medieval parks and their boundaries is one of the many useful tasks awaiting the field-worker with patience and a good local knowledge".[6] Most deer parks were bounded by significant earthworks topped by a park pale, typically of cleft oak stakes.[7] These boundaries typically have a curving, rounded plan, possibly to economise on the materials and work involved in fencing[7] and ditching.

A few deer parks in areas with plentiful building stone had stone walls instead of a park pale.[7] Examples include Barnsdale in Yorkshire and Burghley in Lincolnshire.[7]

Boundary earthworks have survived "in considerable numbers and a good state of preservation".[8] Even where the bank and ditch do not survive, their former course can sometimes still be traced in modern field boundaries.[9] The boundaries of early deer parks often formed parish boundaries. Where the deer park reverted to agriculture, the newly established field system was often rectilinear, clearly contrasting with the system outside the park.

Examples

- Ashdown Park Upper Wood, Oxfordshire (formerly Berkshire)

- Barnsdale, Yorkshire[7]

- Beckley Park, Beckley, Oxfordshire[10]

- Bucknell Wood, Abthorpe, Northamptonshire

- Burghley, Lincolnshire[7]

- Chetwynd Deer Park, Newport, Shropshire

- Flitteriss Park, Leicestershire

- Hatfield Broad Oak, Essex (surviving but not functioning)[1]

- Henley Park, Lower Assendon, Oxfordshire[11]

- Longnor Deer Park, Shropshire

- Moccas Deer Park, Herefordshire (surviving in use)[1]

- Silchester, Hampshire[12]

- Sutton Coldfield Deer Park (surviving but not functioning)[1]

References

- ^ a b c d Rackham, Oliver (1976). Trees and Woodland in the British Landscape. Archaeology in the Field Series. London: J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd. p. 150. ISBN 0 460 04183 5.

- ^ Beresford, Maurice (1998) [1957]. History on the Ground. Sutton Publishing. p. 187. ISBN 0750918845.

- ^ Rackham, Oliver (1997[clarification needed]) [1975]. The History of the Countryside. Phoenix Giant Paperback. p. 125.

- ^ Muir, Richard (2007). Be Your Own Landscape Detective: Investigating Where You Are. Sutton Publishing. p. 241. ISBN 0750943335.

- ^ Rackham, Oliver (1976). Trees and Woodland in the British Landscape. Archaeology in the Field Series. London: J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd. p. 146. ISBN 0 460 04183 5.

- ^ Hoskins, W.G. (1985) [1955]. The Making of the English Landscape. Penguin Books. p. 94. ISBN 0140079645.

- ^ a b c d e f Rackham, Oliver (1976). Trees and Woodland in the British Landscape. Archaeology in the Field Series. London: J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd. p. 144. ISBN 0 460 04183 5.

- ^ Crawford, O.G.S. (1953). Archaeology in the Field. London: Phoenix House. p. 190.

- ^ Liddiard, R. (2007). The Medieval Deer Park: New Perspectives. Windgather Press. p. 178.

- ^ Lobel, Mary D, ed (1957). A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 5: Bullingdon Hundred. Victoria County History. pp. 56–76.

- ^ Emery, Frank (1974). The Oxfordshire Landscape. The Making of the English Landscape. London: Hodder & Stoughton. p. 206. ISBN 0 340 04301 6.

- ^ Page, W.H., ed (1911). A History of the County of Hampshire, Volume 4. Victoria County History. pp. 51–56.

See also

Categories:- Landscape history

- Landscape design history

- Medieval architecture

- Medieval culture

- Parks

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.