- Aztec Triple Alliance

-

This article is about the Aztec Empire as a country. For Aztec society and culture, see Aztec.

Aztec Triple Alliance 1428–1521  →

→Middle section of page 34 of Codex Osuna, from 1565, showing the glyphs for Texcoco, Tenochtitlan, and Tlacopan.

Capital Tenochtitlan Language(s) Nahuatl Religion Aztec religion Government Monarchy Huehuetlatoani of Tenochtitlan complete list - 1427–1440 Itzcoatl (founder of alliance) - 1520–1521 Cuauhtémoc (last) Huetlatoani of Texcoco complete list - 1431–1440 Nezahualcoyotl (founder of alliance) - 1516–1520 Cacamatzin (last) Huetlatoani of Tlacopan - Unknown Totoquihuaztli (founder of alliance) Historical era Pre-Columbian - Foundation of the alliance March 13, 1428 - Spanish conquest August 13, 1521 Currency Quachtli Cocoa Beans

King list:[1] The Aztec Triple Alliance, or Aztec Empire began as an alliance of three Nahua city-states or "altepeme": Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan. These city-states ruled the area in and around the Valley of Mexico from 1428 until they were defeated by the Spanish conquistadores and their native allies under Hernán Cortés in 1521.

The Triple Alliance was formed from the victorious faction in a war between the city of Azcapotzalco and its former tributary provinces.[1] Despite the initial conception of the empire as an alliance of three cities, Tenochtitlan quickly established itself as the dominant partner.[2] By the time the Spanish arrived in 1520, the lands of the Alliance were effectively ruled from Tenochtitlan, and the other partners in the alliance had assumed subsidiary roles.

The alliance waged wars of conquest and expanded rapidly after its formation. At its height, the alliance controlled an empire that covered most of central Mexico as well as some more distant lands. Aztec rule has been described by scholars as "hegemonic" or "indirect".[3] Rulers of conquered cities were usually left in power as long as they agreed to pay semi-annual tribute to the alliance or provided military support in wars with enemy states.

Contents

Etymology

The word "Aztec" is a modern invention and would not have been recognized by the people themselves. It has variously been used to refer to the Triple Alliance empire, the Nahuatl-speaking people of central Mexico prior the Spanish conquest, or the Mexica ethnicity specifically.[4] The name comes from a Nahuatl word meaning "people from Aztlan", reflecting the mythical place of origin for Nahua peoples.[5]

Aztec civilization Human sacrifice Warfare · Aztec codices Aztec Triple Alliance Spanish conquest of Mexico Fall of Tenochtitlan La Noche Triste History

Before the Empire

The Valley of Mexico at the time of the Spanish Conquest.

The Valley of Mexico at the time of the Spanish Conquest.

Nahua peoples were not originally indigenous to central Mexico, and are instead descended from Chichimec peoples who migrated into the region from the north in the early 13th century AD.[6] According to the pictographic codices in which the Aztecs recorded their history, the place of origin was called Aztlán. The early migrants settled the Basin of Mexico and surrounding lands by establishing a series of independent city-states. These early Aztec cities were ruled by petty kings called "tlatoque" (singular "tlatoani"). Most of the cities and towns in the region prior to the Aztec migration were assimilated into Aztec culture.[7]

These early city-states fought various small-scale wars with each other, but due to the shifting nature of alliances no individual city gained dominance.[8] The Mexica were the last of the Aztlan migrants to arrive in Central Mexico. They entered the Basin of Mexico around the year 1250 AD, when most of the good agricultural land was taken.[9] The Mexica persuaded the king of Culhuacan to reluctantly allow them to settle in a relatively infertile patch of land called Tizaapan.[10]

After serving the king of Culhuacan in battle, the Mexica were granted one of his daughters to rule over them. According to mythological native accounts, the Mexica sacrificed her on the command of their god Huitzilopochtli.[11] When the king of Culhuacan witnessed this, he attacked and used his army to drive the Mexica from Tizaapan by force. The Mexica then moved to an island in the middle of Lake Texcoco, where an eagle nested on a nopal cactus. The Mexica interpreted this as a sign from their god, and founded their new city, Tenochtitlan, on this island in the year 2 House (1325 AD).[3]

The new Mexica city allied itself with the city of Azcapotzalco and paid tribute to its king, Tezozomoc.[12] With Mexica assistance, Azcopotzalco began to expand into a small tributary empire. Until this point, the Mexica did not have a legitimate king. Mexica leaders successfully petitioned one of the kings of Culhuacan to provide a daughter to marry into the Mexica line. Their son, Acamapichtli, was enthroned as the first tlatoani of Tenochtitlan in the year 1372.[13]

As the Tepanecs of Azcapotzalco continued to expand their kingdom with the assistance of the Mexica, the Acolhua city of Texcoco grew in power in the eastern portion of the lake basin. War eventually erupted between the two states, and the Mexica played a vital role in the conquest of Texcoco. By this time, Tenochtitlan had grown into a major city and was rewarded for its loyalty to the Tepanecs by receiving Texcoco as a tributary province.[14]

The Tepanec Civil War and the Triple Alliance

In 1426, the Tepanec king Tezozomoc died, and the resulting succession crisis precipitated a civil war.[14] The Mexica supported Tezozomoc's preferred heir Tayahauh who was initially enthroned as king. His brother, Maxtla, soon usurped the throne and turned against those factions that opposed him, including the Mexica king Chimalpopoca. Chimalpopoca died shortly after this, possibly assassinated by Maxtla.[9]

The new Mexica king Itzcoatl remained defiant to Maxtla, and in response Maxtla had Tenochtitlan blockaded and demanded increased tribute payments.[15] Maxtla similarly turned against the Acolhua, and the king of Texcoco, Nezahualcoyotl fled into exile. Nezahualcoyotl recruited the military assistance of the king of Huexotzinco, and the Mexica gained the support of a dissident Tepanec city, Tlacopan. In 1427, Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, Tlacopan, and Huexotzinco went to war with Azcapotzalco and emerged victorious in 1428.[15]

After the war, Huexotzinco withdrew and the three remaining cities formed a treaty known today as the Triple Alliance.[15] The Tepanec lands were carved up between the three cities who agreed to cooperate in future wars of conquest. Land acquired from these conquests was to be held by the three cities together. Tribute was to be divided so that two fifths each went to Tenochtitlan and Texcoco and one fifth went to Tlacopan. Each of the three kings of the alliance in turn assumed the title "huetlatoani" ("Elder Speaker", often translated as "Emperor"), which placed them in a de jure position above the rulers of other city-states ("tlatoani").[16]

The Triple Alliance of Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan would, in the next 100 years, come to dominate the Valley of Mexico and extend its power to both the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific shore. Over this period, Tenochtitlan gradually became the dominant power in the alliance. Two of the primary architects of this alliance were the half-brothers Tlacaelel and Motecuzoma, nephews of Itzcoatl. Motecuzoma would eventually succeed Itzcoatl as the Mexica huetlatoani in 1440. Tlacaelel occupied the newly created title of "Cihuacoatl", roughly equivalent to "Prime Minister".[15]

Imperial Reforms

Shortly after the formation of the Triple Alliance, Itzcoatl and Tlacaelel instigated sweeping reforms the Aztec state and religion. Tlacaelel ordered the burning of most of the extant Aztec books, claiming that they contained lies and that it was "not wise that all the people should know the paintings".[17] He thereafter rewrote the history of the Aztec people, placing the Mexica in a more central role.

After Motecuzoma I succeeded Itzcoatl as the Mexica emperor, more reforms were instigated to maintain control over conquered cities.[18] Uncooperative kings were replaced with puppet rulers loyal to the Mexica. A new imperial tribute system established Mexica tribute collectors that taxed the population directly, bypassing the authority of local dynasties. Nezahualcoyotl also instituted a policy in the Acolhua lands of granting subject kings tributary holdings in lands far from their capitals.[19] This was done to create an incentive for cooperation with the empire; if a city's king rebelled, he lost the tribute he received from foreign land. Some rebellious kings were replaced by "calpixque", or appointed governors rather than dynastic rulers.[19]

Motecuzoma issued new laws that further separated nobles from commoners and instituted the death penalty for adultery and other offenses.[20] By royal decree, a religiously-supervised school was built in every neighborhood.[20] Commoner neighborhoods had a school called a "telpochcalli" where they received basic religious instruction and military training.[21] A second, more prestigious type of school called a "calmecac" served to teach the nobility, as well as commoners of high standing seeking to become priests or artisans. Motecuzoma also created a new title called "quauhpilli" that could be conferred on commoners.[18] This title was a form of non-hereditary lesser nobility awarded for outstanding military or civil service (similar to the English knight). In some rare cases, commoners that received this title married into royal families and became kings.[19]

One component of this reform was the creation of ritual wars called the Flower Wars. These wars created a steady supply of experienced Aztec warriors and war captives for human sacrifice. Flower wars were pre-arranged by the emperors and enemy cities and conducted specifically for the purpose of collecting prisoners for sacrifice.[22] According to native historical accounts, these wars were instigated by Tlacaelel as a means of appeasing the gods in response to a massive drought that gripped the Basin of Mexico from 1450-4.[23] The flower wars were mostly waged between the Aztec Empire and the neighboring cities of Tlaxcala.

Early Wars of Expansion

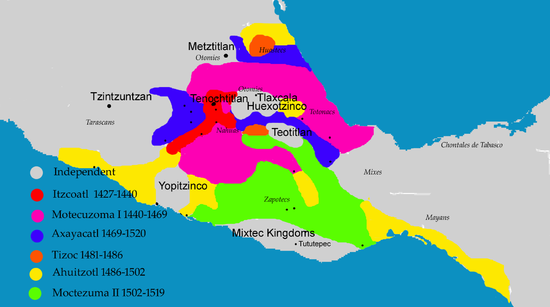

Map showing the expansion of the Aztec empire showing the areas conquered by the Aztec rulers.[24]

Map showing the expansion of the Aztec empire showing the areas conquered by the Aztec rulers.[24]

After the defeat of the Tepanecs, Itzcoatl and Nezahualcoyotl rapidly consolidated power in the Basin of Mexico and began to expand beyond its borders. The first targets for imperial expansion were Coyoacan in the Basin of Mexico and Cuauhnahuac and Huaxtepec in the modern Mexican state of Morelos.[25] These conquests provided the new empire with a large influx of tribute, especially agricultural goods.

On the death of Itzcoatl, Motecuzoma I was enthroned as the new Mexica emperor. The expansion of the empire was briefly halted by a major four-year drought that hit the Basin of Mexico in 1450, and several cities in Morelos had to be re-conquered after the drought subsided.[26] Motecuzoma and Nezahualcoyotl continued to expand the empire east towards the Gulf of Mexico and south into Oaxaca. In 1468, Motecuzoma I died and was succeeded by his son, Axayacatl. Most of Axayacatl's thirteen-year-reign was spent consolidating the territory acquired under his predecessor. Motecuzoma and Nezahualcoyotl had expanded rapidly and many provinces rebelled.[9]

At the same time as the Aztec Empire was expanding and consolidating power, the Tarascan Empire in West Mexico was similarly expanding. In 1455, the Tarascans under their king Tzitzipandaquare had invaded the Toluca Valley, claiming lands previously conquered by Motecuzoma and Itzcoatl.[27] In 1472, Axayacatl re-conquered the region and successfully defended it from Tarascan attempts to take it back. In 1479, Axayacatl launched a major invasion of the Tarascan Empire with 32,000 Aztec soldiers.[27] The Tarascans met them just across the border with 50,000 soldiers and scored a resounding victory, killing or capturing over 90% of the Aztec army. Axayacatl himself was wounded in the battle, retreated to Tenochtitlan, and never engaged the Tarascans in battle again.[28]

In 1472, Nezahualcoyotl died and his son Nezahualpilli was enthroned as the new huetlatoani of Texcoco.[29] This was followed by the death of Axayacatl in 1481.[28] Axayacatl was replaced by his brother Tizoc. Tizoc's reign was notoriously brief. He proved to be ineffectual and did not significantly expand the empire. Due to his apparent incompetence, Tizoc was likely assassinated by his own nobles five years into his rule.[28]

Later Wars of Expansion

Tizoc was succeeded by his brother Ahuitzotl in 1486. Like his predecessors before him, the first part of Ahuitzotl's reign was spent suppressing rebellions which were commonplace due to the indirect nature of Aztec rule.[28] Ahuitzotl then began a new wave of conquests including the Valley of Oaxaca and the Soconusco Coast. Due to increased border skirmishes with the Tarascans, Ahuitzotl conquered the border city of Otzoma and turned the city into a military outpost.[30] The population of Otzoma was either killed or dispersed in the process.[27] The Tarascans subsequently established fortresses nearby to protect against Aztec expansion.[27] Ahuitzotl responded by expanding further west to the Pacific Coast of Guerrero.

By the reign of Ahuitzotl, the Mexica were the largest and most powerful faction in the Aztec Triple Alliance.[31] Building upon the prestige the Mexica had acquired over the course of the conquests, Ahuitzotl began to use the title "huehuetlatoani" ("Eldest Speaker") to distinguish himself from the rulers of Texcoco and Tlacopan.[28] Even though the alliance still technically ran the empire, the Mexica Emperor now assumed nominal if not actual seniority.

Ahuitzotl was succeeded by his brother Motecuzoma II in 1502. Motecuzoma II spent most of his reign consolidating power in lands conquered by his predecessors.[30] In 1515, Aztec armies commanded by the Tlaxcalan general Tlahuicole invaded the Tarascan Empire once again.[32] The Aztec army failed to take any territory and was mostly restricted to raiding. The Tarascans defeated them and the army withdrew.

Motecuzoma II instituted more imperial reforms.[30] After the death of Nezahualcoyotl, the Mexica Emperors had become the de facto rulers of the alliance. Motecuzoma II used his reign to attempt to consolidate power more closely with the Mexica Emperor.[33] He removed many of Ahuitzotl's advisors and had several of them executed.[30] He also abolished the "quauhpilli" class, destroying the chance for commoners to advance to the nobility. His reform efforts were inevitably cut short by the Spanish Conquest in 1519.

Spanish conquest and Aztec defeat

Main article: Spanish conquest of the Aztec EmpireThe empire reached its height during Ahuitzotl's reign in 1486–1502. His successor, Motehcuzōma Xocoyotzin (better known as Moctezuma II or Moctezuma), had been Hueyi Tlatoani for 17 years when the Spaniards, led by Hernán Cortés, landed on the Gulf Coast in the spring of 1519.

Despite some early battles between the two, Hernán Cortés allied himself with the Aztecs' long-time enemy, the Confederacy of Tlaxcala, and arrived at the gates of Tenochtitlan on November 8, 1519.

The Spaniards and their Tlaxcallan allies became increasingly dangerous and unwelcome guests in the capital city. In June, 1520, hostilities broke out, culminating in the massacre in the Main Temple and the death of Moctezuma II. The Spaniards fled the town on July 1, an episode later characterized as La Noche Triste (the Sad Night). They and their native allies returned in the spring of 1521 to lay siege to Tenochtitlan, a battle that ended on August 13 with the destruction of the city. During this period the now crumbling empire went through a rapid line of ruler succession. After the death of Moctezuma II, the empire fell into the hands of severely weakened emperors, such as Cuitláhuac, before eventually being ruled by puppet rulers, such as Andrés de Tapia Motelchiuh, installed by the Spanish.

Despite the decline of the Aztec Empire, most of the Mesoamerican cultures were intact after the fall of Tenochtitlan. Indeed, the freedom from Aztec domination may have been considered a positive development by most of the other cultures. The upper classes of the Aztec empire were considered noblemen by the Spaniards and generally treated as such initially. All this changed rapidly and the native population were soon forbidden to study by law, and had the status of minors[citation needed].

The Tlaxcalans remained loyal to their Spanish friends and were allowed to come on other conquests with Cortés and his men.

See also

- Aztec

- Spanish conquest of Mexico

- Flower war

Reference

- ^ a b Smith 1997

- ^ Hassig 1988

- ^ a b Smith 2001

- ^ Smith 2007 pp.3-4

- ^ Smith 1984

- ^ Davies 1973, pp. 3-22

- ^ Smith 2001 p. 37

- ^ Calnek 1978

- ^ a b c Davies 1973

- ^ Alvarado Tezozomoc 1975 pp. 49-51

- ^ Smith 2001 p. 43

- ^ Smith 2001 p. 44

- ^ Alvarado Tezozomoc 1975

- ^ a b Smith 2001 p. 46

- ^ a b c d Smith 2001 p.47

- ^ Evans 2008, p. 460

- ^ Leon-Portilla 1963 p.155

- ^ a b Smith 2001 p. 48

- ^ a b c Evans 2008 p. 462

- ^ a b Duran 1994, pp. 209-210

- ^ Evans 2008 p. 456-457

- ^ Evans 2008, p. 451

- ^ Duran 1994

- ^ Based on Hassig 1988.

- ^ Smith 2001 p. 47-48

- ^ Smith 2001 p. 49

- ^ a b c d Pollard 1993, p.169

- ^ a b c d e Smith 2001 p. 51

- ^ Evans 2008, p.450

- ^ a b c d Smith 2001 p. 54

- ^ Smith 2001 p.50-51

- ^ Pollard 1993 pp. 169-170

- ^ Davies 1973 p. 216

Bibliography

- Alvarado Tezozomoc, Hernando de (1975). Crónica Mexicáyotl. Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico, Mexico City.

- Calnek, Edward (1978). R. P. Schaedel, J. E. Hardoy, and N. S. Kinzer. ed. Urbanization of the Americas from its Beginnings to the Present. pp. 463–470.

- Davies, Nigel (1973). The Aztecs: A History. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman.

- Duran, Diego (1992). History of the Indies of New Spain. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman.

- Evans, Susan T. (2008). Ancient Mexico and Central America: Archaeology and Culture History, 2nd edition. Thames & Hudson, New York. ISBN 978-0-500-28714-9.

- Hassig, Ross (1988). Aztec Warfare: Imperial Expansion and Political Control. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2121-1.

- Leon-Portilla, Miguel (1963). Aztec Thought and Culture: A Study of the Ancient Náhuatl Mind. University of Oklahoma Press.

- Pollard, H. P. (1993). Tariacuri's Legacy.. University of Oklahoma Press..

- Smith, Michael (1984). "The Aztec Migrations of Nahuatl Chronicles: Myth or History?". Ethnohistory 31(3): 153–168.

- Smith, Michael E. (1997). The Aztecs. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-23015-7.

- Smith, Michael (2001). "The Archaeological Study of Empires and Imperialism in Pre-Hispanic Central Mexico". Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 20: 245–284. doi:10.1006/jaar.2000.0372.

Categories:- Former monarchies of North America

- Former countries in North America

- States and territories established in 1428

- States and territories disestablished in 1521

- 1428 in Mexico

- 1521 in Mexico

- Aztec history

- Former empires of the Americas

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.