- Aztec codices

-

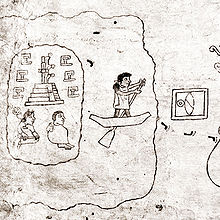

Detail of first page from the Boturini Codex, depicting the departure from Aztlán.

Detail of first page from the Boturini Codex, depicting the departure from Aztlán.

Aztec codices are books written by pre-Columbian and colonial-era Aztecs. These codices provide some of the best primary sources for Aztec culture.

The pre-Columbian codices differ from European codices in that they are largely pictorial; they were not meant to symbolize spoken or written narratives.[1] The colonial era codices not only contain Aztec pictograms, but also Classical Nahuatl (in the Latin alphabet), Spanish, and occasionally Latin.

Although there are very few surviving pre-conquest codices, the tlacuilo (codex painter) tradition endured the transition to colonial culture; scholars now have access to a body of around 500 colonial-era codices.

According to the Madrid Codex, the fourth tlatoani Itzcoatl (ruling from 1427 (or 1428) to 1440) ordered the burning of all historical codices because it was "not wise that all the people should know the paintings".[2] Among other purposes, this allowed the Aztec state to develop a state-sanctioned history and mythos that venerated Huitzilopochtli.

Contents

Codex Borbonicus

Page 13 of the Codex Borbonicus. Main article: Codex Borbonicus

Main article: Codex BorbonicusThe Codex Borbonicus is a codex written by Aztec priests shortly before or after the Spanish conquest of Mexico. Like all pre-Columbian codices, it was originally entirely pictorial in nature, although some Spanish descriptions were later added. It can be divided into three sections:

- An intricate tonalamatl, or divinatory calendar;

- A documentation of the Mesoamerican 52 year cycle, showing in order the dates of the first days of each of these 52 solar years; and

- A section of rituals and ceremonies, particularly those that end the 52 year cycle, when the "new fire" must be lit.

Boturini Codex

The Boturini Codex was painted by an unknown Aztec author some time between 1530 and 1541, roughly a decade after the Spanish conquest of Mexico. Pictorial in nature, it tells the story of the legendary Aztec journey from Aztlán to the Valley of Mexico.

Rather than employing separate pages, the author used one long sheet of amatl, or fig bark, accordion-folded into 21½ pages. There is a rip in the middle of the 22nd page, and it is unclear whether the author intended the manuscript to end at that point or not. Unlike many other Aztec codices, the drawings are not colored, but rather merely outlined with black ink.

Also known as “Tira de la Peregrinación” ("The Strip Showing the Travels"), it is named after one of its first European owners, Lorenzo Boturini Bernaducci (1702 – 1751). It is now held in the Museo Nacional de Antropología in Mexico City.

Codex Mendoza

Main article: Codex MendozaThe Codex Mendoza is a pictorial document, with Spanish annotations and commentary, composed circa 1541. It is divided into three sections: a history of each Aztec ruler and their conquests; a list of the tribute paid by each tributary province; and a general description of daily Aztec life.

Florentine Codex

Main article: Florentine CodexThe Florentine Codex is a set of 12 books created under the supervision of Bernardino de Sahagún between approximately 1540 and 1585. It is a copy of original source materials which are now lost, perhaps destroyed by the Spanish authorities who confiscated Sahagún's manuscripts. Perhaps more than any other source, the Florentine Codex has been the major source of Aztec life in the years before the Spanish conquest even though a complete copy of the codex, with all illustrations, was not published until 1979. Before then, only the censored and rewritten Spanish translation had been available.

Codex Osuna

The Codex Osuna is a set of seven separate documents created in early 1565 to present evidence against the government of Viceroy Luis de Velasco during the 1563-66 inquiry by Jerónimo de Valderrama. In this codex, indigenous leaders claim non-payment for various goods and for various services performed by their people, including building construction and domestic help.

The Codex was originally solely pictorial in nature. Nahuatl descriptions and details were then entered onto the documents during its review by Spanish authorities, and a Spanish translation of the Nahuatl was added.

Aubin Codex

The Aubin Codex is a pictorial history of the Aztecs from their departure from Aztlán through the Spanish conquest to the early Spanish colonial period, ending in 1607. Consisting of 81 leaves, it was most likely begun in 1576, it is possible that Fray Diego Durán supervised its preparation, since it was published in 1867 as Historia de las Indias de Nueva-España y isles de Tierra Firme, listing Durán as the author.

Among other topics, the Aubin Codex has a native description of the massacre at the temple in Tenochtitlan in 1520.

Also called "Manuscrito de 1576" (“The Manuscript of 1576”), this codex is held by the British Museum and a copy of its commentary at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. A copy of the original is held at the Princeton University library in the Robert Garrett Collection there. The Aubin Codex is not to be confused with the similarly named Aubin Tonalamatl.

Codex Magliabechiano

Reverse of folio 11 of the Codex Magliabechiano, showing the day signs Flint (knife), Rain, Flower, and Crocodile.

Reverse of folio 11 of the Codex Magliabechiano, showing the day signs Flint (knife), Rain, Flower, and Crocodile.

The Codex Magliabechiano was created during the mid-16th century, in the early Spanish colonial period. Based on an earlier unknown codex, the Codex Magliabechiano is primarily a religious document, depicting the 20 day-names of the tonalpohualli, the 18 monthly feasts, the 52-year cycle, various deities, indigenous religious rites, costumes, and cosmological beliefs.

The Codex Magliabechi has 92 pages made from European paper, with drawings and Spanish language text on both sides of each page.

It is named after Antonio Magliabechi, a 17th century Italian manuscript collector, and is presently held in the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, Florence, Italy.

Codex Cozcatzin

The Codex Cozcatzin is a post-conquest, bound manuscript consisting of 18 sheets (36 pages) of European paper, dated 1572 although was perhaps created later than this. Largely pictorial, it has short descriptions in Spanish and Nahuatl.

The first section of the codex contains a list of land granted by Itzcóatl in 1439 and is part of a complaint against Diego Mendoza. Other pages list historical and genealogical information, focused on Tlatelolco and Tenochtitlan. The final page consists of astronomical descriptions in Spanish.

It named for Don Juan Luis Cozcatzin, who appears in the codex as "alcalde ordinario de esta ciudad de México" ("ordinary mayor of this city of Mexico"). The codex is presently held by the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris.

Codex Ixtlilxochitl

The Codex Ixtlilxochitl is an early 17th century codex fragment detailing, among other subjects, a calendar of the annual festivals and rituals celebrated by the Aztec teocalli during the Mexican year. Each of the 18 months is represented by a god or historical character.

Written in Spanish, the Codex Ixtlilxochitl has 50 pages comprising 27 separate sheets of European paper with 29 drawings. It was derived from the same source as the Codex Magliabechiano. It was named after Fernando de Alva Cortés Ixtlilxochitl (between 1568 & 1578 - c. 1650), a member of the ruling family of Texcoco, and is held in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris.

Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis

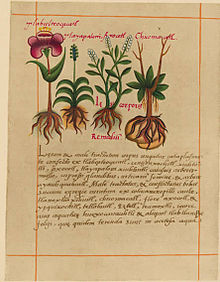

A page of the Libellus illustrating the tlahçolteoçacatl, tlayapaloni, axocotl and chicomacatl plants.

A page of the Libellus illustrating the tlahçolteoçacatl, tlayapaloni, axocotl and chicomacatl plants. Main article: Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis

Main article: Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum HerbisThe Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis (Latin for "Little Book of the Medicinal Herbs of the Indians") is a herbal manuscript, describing the medicinal properties of various plants used by the Aztecs. It was translated into Latin by Juan Badiano, from a Nahuatl original composed in Tlatelolco in 1552 by Martín de la Cruz that is no longer extant. The Libellus is also known as the Badianus Manuscript, after the translator; the Codex de la Cruz-Badiano, after both the original author and translator; and the Codex Barberini, after Cardinal Francesco Barberini, who had possession of the manuscript in the early 17th century.

Other codices

- Codex Borgia - pre-Hispanic ritual codex. The name is also given to a number of codices called the Borgia Group:

- Codex Laud

- Codex Vaticanus B

- Codex Cospi

- Codex Fejérváry-Mayer - pre-Hispanic calendar codex.

- Codex Telleriano-Remensis - calendar, divinatory almanac and history of the Aztec people.

- Codex Ríos - an Italian translation and augmentation of a the Codex Telleriano-Remensis.

- Ramírez Codex - a history by Juan de Tovar.

- Anales de Tlatelolco a.k.a. "Unos Anales Históricos de la Nación Mexicana" - post-conquest.

- Durán Codex - a history by Diego Durán.

- Codex Xolotl - a pictorial codex recounting the history of the Valley of Mexico, and Texcoco in particular, from Xolotl's arrival in the Valley to the defeat of Azcapotzalco in 1428.

- Codex Azcatitlan

- Mapa de Cuauhtinchan No. 2 - a post-conquest indigenous map, legitimazing the land rights of the Cuauhtinchantlacas.

- History of Tlaxcala, aka Lienzo de Tlaxcala - written by and under the supervision of Diego Muñoz Camargo in the years leading up to 1585.

Aztec civilization Human sacrifice Warfare · Aztec codices Aztec Triple Alliance Spanish conquest of Mexico Fall of Tenochtitlan La Noche Triste See also

- Codex Zouche-Nuttall - one of the Mixtec codices. Codex Zouche-Nuttall is currently in the British Museum.

- Crónica X

References

- ^ Elizabeth Hill Boone, "Pictorial Documents and Visual Thinking in Postconquest Mexico". p. 158.

- ^ Madrid Codex, VIII, 192v, as quoted in León-Portilla, p. 155. León-Portilla, Miguel (1963). Aztec Thought and Culture: A Study of the Ancient Náhuatl Mind. Civilization of the American Indian series, no. 67. Jack Emory Davis (trans.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. OCLC 181727. Note that León-Portilla finds Tlacaelel to be the instigator of this burning, despite lack of specific historical evidence.[verification needed]

External links

Categories:- Aztec

- Aztec codices

- Manuscripts by area

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.