- Florentine Codex

-

The Florentine Codex is the common name given to a 16th century ethnographic research project in Mesoamerica by Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún. Bernardino originally titled it: La Historia General de las Cosas de Nueva Espana (in English: the General History of the Things of New Spain).[1] It is commonly referred to as "The Florentine Codex" after the Italian archive library where the best-preserved manuscript is preserved. In partnership with Aztec men who were formerly his students, Bernardino conducted research, organized evidence, wrote and edited his findings starting in 1545 up until his death in 1590. It consists of 2400 pages organized into twelve books with over 2000 illustrations drawn by native artists providing vivid images of this era. It documents the culture, religious cosmology (worldview) and ritual practices, society, economics, and natural history of the Aztec people. One scholar described The Florentine Codex as “one of the most remarkable accounts of a non-Western culture ever composed.”[2] Charles E. Dibble and Arthur J. O. Anderson were the first to translate the Codex from Nahuatl to English, in a project that took 30 years to complete.[3]

Contents

Bernardino’s motivations for research

Bernardino’s primary motivation was to evangelize indigenous Mesoamerican peoples, and his writings were devoted to this end. He described this work as an explanation of the “divine, or rather idolatrous, human, and natural things of New Spain.”[4] He compared its body of knowledge to that needed by a physician to cure the “patient” suffering from idolatry. He had three overarching goals for his research:

1. To describe and explain ancient Indigenous religion, beliefs, practices, deities. This was to help friars and others understand this “idolatrous” religion and to evangelize the Aztecs.

2. To create a vocabulary of the Aztec language, Nahuatl. This provides more than definitions from a dictionary, but rather an explanation of their cultural origins, with pictures. This was to help friars and others learn Nahuatl, but also to understand the cultural context of the language.

3. To record and document the great cultural inheritance of the Indigenous peoples of New Spain.[5]

Bernardino conducted research for several decades, edited and revised it over several decades, created several versions of a 2400 page manuscript, and addressed a cluster of religious, cultural and nature themes.[6] Copies of it were sent back to the royal court of Spain and to the Vatican in the late 16th century to explain Aztec culture. The document was essentially lost for about two centuries, until a scholar rediscovered it in an archive library in Florence, Italy. A scholarly community of historians, anthropologists, art historians, and linguists has been actively investigating Bernardino’s work, its subtleties and mysteries, for more than 200 years.[7]

Format and structure

The Florentine Codex is a complex document, assembled, edited, and appended over decades. Bernardino’s goals of orientating fellow missionaries to Aztec culture, providing a rich Nahuatl vocabulary, and recording the indigenous cultural heritage at times compete with each other within it. The manuscript pages are generally of two columns, with Nahuatl, written first, on the right and a Spanish translation on the left. There are diverse voices, views, and opinions in these 2400 pages, and the result is document than can, at times, appear contradictory.[8]

Scholars have proposed several classical and medieval worldbook authors that inspired Bernardino, such as Aristotle, Pliny, Isidore of Seville, and Bartholomew the Englishman. These shaped the late medieval approach to the organization of knowledge.[9] The twelve books of the Florentine Codex are organized in the following way:

1. Gods, religious beliefs and rituals, cosmology, and moral philosophy,

2. Humanity (society, politics, economics, including anatomy and disease),

3. Natural history.

The story of the conquest of Mexico is appended to the end of this presentation.

This follows the organizational flow of logic found in medieval encyclopedias, in particular the 19-volume De proprietatibus rerum of his fellow Franciscan Friar Bartholomew the Englishman. One scholar has argued that Bartholomew’s work served as a conceptual model for Bernardino, although evidence is circumstantial.[10] With more confidence one can assert that both of these present the cosmos, society and nature of the late medieval paradigm.[11]

The 12 books[12]

1. The Gods. Deals with gods worshiped by the natives of this land, which is New Spain.

2. The Ceremonies. Deals with holidays and sacrifices with which these natives honored their gods in times of infidelity.

3. The Origin of the Gods. About the creation of the gods.

4. The Soothsayers. About Indian judiciary astrology or omens and fortune-telling arts.

5. The Omens. Deals with foretelling these natives made from birds, animals, and insects in order to foretell the future.

6. Rhetoric and Moral Philosophy. About prayers to their gods, rhetoric, moral philosophy, and theology in the same context.

7. The Sun, Moon and Stars, and the Binding of the Years. Deals with the sun, the moon, the stars, and the jubilee year.

8. Kings and Lords. About kings and lords, and the way they held their elections and governed their reigns.

9. The Merchants. About merchants, and officials for gold, precious stones and feathers.

10. The People. About general history: it explains vices and virtues, spiritual as well as bodily, of all manner of persons.

11. Earthly Things. About properties of animals, birds, fish, trees, herbs, flowers, metals, and stones, and about colors.

12. The Conquest. About the conquest of New Spain, which is Mexico City.

Ethnographic methodologies

Bernardino was among the first to develop a bundle of strategies for gathering and validating knowledge of indigenous New World cultures. Much later, the scientific discipline of anthropology would later formalize these as ethnography (the scientific research strategy to document the beliefs, behavior, social roles and relationships, and worldview of another culture, but to explain these within the logic of that culture). Ethnography requires the practice of empathy with those very different from oneself, and the suspension of one’s own cultural beliefs in order to understand and explain the worldview of those living in another culture. Bernardino systematically gathered knowledge from a range of diverse informants who were recognized as having expert knowledge of Aztec culture. He gathered knowledge from a range of diverse informants who were recognized as having knowledge of cultural tradition. He did so in the native language of Nahuatl, but then compared the answers from different sources of information. He sought out different kinds of informants, including women (which was unusual). Some passages appear to be the transcription of spontaneous narration of religious beliefs, society or nature. Other parts clearly reflect a consistent set of questions presented to different people designed to elicit specific information. Some sections of text report Bernardino’s own narration of events or commentary. He developed a methodology with the following elements:

1. He used the native language of Nahuatl.

2. He dialogued with elders, cultural authorities publicly recognized as most knowledgeable.

3. He adapted himself to the ways in which Aztec culture recorded and transmitted knowledge.

4. He used the expertise of his former students.

5. He attempted to capture the totality or complete reality of Aztec culture on its own terms.

6. He structured his inquiry, using questionnaires, but was prepared to set this aside when more valuable information was shared through other means.

7. He attended to the diverse ways in which diverse meanings are transmitted through Nahuatl.

8. He undertook a comparative evaluation of information, drawing from multiple sources, in order to determine the degree of confidence with which he could hold that information.

These methodological innovations substantiate the claim Bernardino was the first anthropologist.

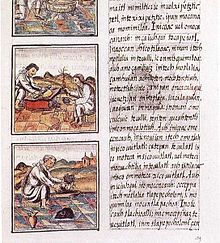

Most of the Florentine Codex is text, but its 2000 pictures provide vivid images of 16th century New Spain. Some of these pictures directly support the text; others are thematically related; others are for decorative purposes. Some are colorful large, and consume most of a page; others are black and white sketches. The illustrations offer remarkable detail about life in New Spain, but they do not bear titles, and the relationship of some to the adjoining text is not always self-evident. They can be considered a “third column of language” in the manuscript. Several different artists’ hands have been identified, and many questions about their accuracy have been raised. The drawings convey a blend of Indigenous and European artistic elements and cultural influences.[13]

Many passages of the texts in the Florentine Codex present descriptions of like items (e.g., gods, classes of people, animals) according to consistent patterns, and it appears that Bernardino deployed a series of questionnaires to structure his interviews.[14] The following questions appear to have been used to gather information about the gods for book one:1. What are the titles, the attributes, or the characteristics of the god?

2. What were his powers?

3. What ceremonies were performed in his honor?

4. What was his attire?

For book ten, a questionnaire may have been used gather information about the social organization of labor and workers, with questions such as:

1. What is the (merchant, artisan) called and why?

2. What particular gods did they venerate?

3. How were their gods attired?

4. How were they worshiped?

5. What do they produce?

6. How did each occupation work?

This book also described the other cultural groups in Mesoamerica.

Bernardino was particularly interested in Aztec medicine. This was not trivial, since many thousands of people died from plagues and diseases, including friars and students at the school. Sections of books ten and eleven describe human anatomy, disease, and medicinal plant remedies.[15] Bernardino named more than a dozen Aztec “doctors” who dictated and edited these sections. The passage on human anatomy appears primarily intended to record vocabulary. A questionnaire such as the following may have been used:1. What is the name of the plant (plant part)?

2. What does it look like?

3. What does it cure?

4. How is the medicine prepared?

5. How is it administered?

6. Where is it found?

The text in this section provides very detailed information about location, cultivation, and medical uses of plants and plant parts. The drawings in this section provide important visual information to supplement the text.

The eleventh book, “Earthly Things,” has the most text and approximately half of the drawings in the codex. Bernardino describes it as a “forest, garden, orchard of the Mexican language.”[16] It describes the Aztec cultural understanding of the animals, birds, insects, fish and trees in Mesoamerica. Apparently Bernardino designed a questionnaire about animals such as the following:1. What is the name of the animal?

2. What animals does it resemble?

3. Where does it live?

4. Why does it receive this name?

5. What does it look like?

6. What habits does it have?

7. What does it feed on?

8. How does it hunt?

9. What sounds does it make?

Plants and animals are described in association with their behavior and natural conditions or habitat. But then the responses of the Aztecs presented their information in a fashion that was consistent with their worldview. This led in some cases to contradictory and somewhat confusing presentations of information. There are also sections on minerals, mining, bridges, roads and food crops.

The Florentine Codex is one of the most remarkable social science research projects ever conducted. It is not unique as a chronicle of encountering the new world and its people, for there were others in this era. Bernardino’s methods for gathering information from the perspective from within a foreign culture were highly unusual for this time. He reported the worldview of people of Mesoamerica as they understood it, and not exclusively from the European perspective. “The scope of the Historia's coverage of contact-period Central Mexico indigenous culture is remarkable, unmatched by any other sixteenth-century works that attempted to describe the native way of life.”[17] Foremost in his own mind, Bernardino was a Franciscan missionary, but he may also rightfully claim the title as Father of American Ethnography.[18]Gallery of Images from the Florentine Codex

See also

References

- ^ Bernardino de Sahagún, Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain (Translation of and Introduction to Historia General De Las Cosas De La Nueva España; 12 Volumes in 13 Books ), trans. Charles E. Dibble and Arthur J. O Anderson (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1950-1982). Images are taken from Fray Bernadino de Sahagún, The Florentine Codex. Complete digital facsimile edition on 16 DVDs. Tempe, Arizona: Bilingual Press, 2009. Reproduced with permission from Arizona State University Hispanic Research Center.

- ^ H. B. Nicholson, "Fray Bernardino De Sahagún: A Spanish Missionary in New Spain, 1529-1590," in Representing Aztec Ritual: Performance, Text, and Image in the Work of Sahagún, ed. Eloise Quiñones Keber (Boulder: University of Colorado Press, 2002).

- ^ http://unews1.utah.edu/news_releases/u-distinguished-professor-of-anthropology-professor-charles-dibble-dies

- ^ H. B. Nicholson, "Fray Bernardino De Sahagún: A Spanish Missionary in New Spain, 1529-1590," in Representing Aztec Ritual: Performance, Text, and Image in the Work of Sahagún, ed. Eloise Quiñones Keber (Boulder: University of Colorado Press, 2002). Prologue to Book XI, Introductory Volume, page 46.

- ^ Alfredo López Austin, "The Research Method of Fray Bernardino De Sahagún: The Questionnaires," in Sixteenth-Century Mexico: The Work of Sahagún, ed. Munro S. Edmonson (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1974). Page 121.

- ^ Edmonson, M. S. (Ed.) (1974) Sixteenth-century Mexico: The Work of Sahagún, Albuquerque, New Mexico, University of New Mexico Press.

- ^ For a history of this scholarly work, see Miguel León-Portilla, Bernardino De Sahagún: The First Anthropologist (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2002).

- ^ For a history of this scholarly work, see Miguel León-Portilla, Bernardino De Sahagún: The First Anthropologist (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2002).

- ^ López Austin, "The Research Method of Fray Bernardino De Sahagún: The Questionnaires."

- ^ D. Robertson, "The Sixteenth Century Mexican Encyclopedia of Fray Bernardino De Sahagún," Journal of World History 4 (1966).

- ^ López Austin, "The Research Method of Fray Bernardino De Sahagún: The Questionnaires."

- ^ Bernardino de Sahagún, Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain (Translation of and Introduction to Historia General De Las Cosas De La Nueva España; 12 Volumes in 13 Books).

- ^ For analysis of the pictures and the artists, see several contributions to John Frederick Schwaller, ed., Sahagún at 500: Essays on the Quincentenary of the Birth of Fr. Bernardino De Sahagún (Berkeley: Academy of American Franciscan History, 2003).

- ^ López Austin, "The Research Method of Fray Bernardino De Sahagún: The Questionnaires."

- ^ Alfredo López Austin, "Sahagún's Work and the Medicine of the Ancient Nahuas: Possibilities for Study," in Sixteenth-Century Mexico: The Work of Sahagún, ed. Munro S. Edmonson (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1974). The ethnobotanic section is an insertion into book eleven, and reads quite differently than the rest of this book.

- ^ Bernardino de Sahagún, Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain (Translation of and Introduction to Historia General De Las Cosas De La Nueva España; 12 Volumes in 13 Books )., Prologue to Book XI, Introductory Volume, page 88.

- ^ Nicholson, "Fray Bernardino De Sahagún: A Spanish Missionary in New Spain, 1529-1590." page 27.

- ^ Arthur J. O Anderson, "Sahagún: Career and Character," in Florentine Codex: Introductions and Indices, ed. Arthur J. O Anderson and Charles E. Dibble (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1982).

Categories:- Mesoamerican codices

- Nahuatl literature

-

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.