- NoMad

-

Coordinates: 40°44′39″N 73°59′18″W / 40.7442°N 73.9883°W

NoMad

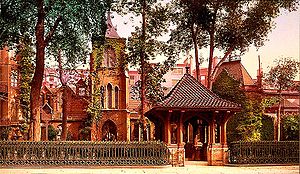

Parts of Broadway in NoMad, such as this block between 26th and 27th Streets remain full of small "wholesale" import shops.The Church of the Transfiguration (seen here in 1900), special to theatre people since 1870, when another church's pastor refused the funeral of an actor, George Holland, and suggested it go to "the little church around the corner."[1]The Armory Show in 1913 was a seminal event in the history of Modern ArtNoMad ("NOrth of MADison Square Park") is a neighborhood centered around the Madison Square North Historic District in the borough of Manhattan in New York City.

The name NoMad, which has been in use since 1999,[3][4] is derived from the area’s location north and west of Madison Square Park. The neighborhood extends roughly from 25th Street to 30th Street between the Avenue of the Americas (Sixth Avenue) and Lexington Avenue. NoMad is bounded on the west by Chelsea, on the northwest by Midtown South, on the northeast by Murray Hill on the east by Rose Hill, and on the south by the Flatiron District. It encompasses Little India, aka "Curry Hill",[5] as well as a variety of businesses of all sizes in landmarked office buildings.[6] NoMad is part of New York City's Manhattan Community Board 5.[7]

Contents

History

NoMad's early history is closely aligned with that of Madison Square Park, which has been a public space since 1686. The park extends from Fifth Avenue to Madison Avenue between 23rd and 26th Streets.[8] Formerly a military parade ground that to this day serves as the starting point for the city's annual Veterans Day Parade, Madison Square Park and the surrounding area have undergone a number of changes since pre-Revolutionary War days, serving at various times as a potter’s field, an army arsenal and a facility for juvenile delinquents.[9]

New Yorkers began establishing residences around the park in the mid-nineteenth century. Private brownstone dwellings and mansions springing up around the perimeter of the park soon boasted such respected, well-to-do families as the Haights, Stokeses, Scheifflins, Wolfes, and Barlows. Leonard and Clara Jerome, the grandparents of Winston Churchill, lived at 41 East 26th Street. The Jerome Mansion later became the clubhouse of the Union League Club of New York (its second location), the University Club and, finally, the Manhattan Club, birthplace of the Manhattan cocktail and congregating place of such famous Democrats as Franklin D. Roosevelt, Grover Cleveland and Al Smith.[10] The mansion was demolished in 1967[11] and was replaced in 1974 by the Merchandise Mart, which also extends onto the site of the adjacent Madison Square Hotel, where actors Henry Fonda and James Stewart roomed in the 1930s.[12]

The famous families in the area nurtured the spiritual life of the neighborhood, founding such landmark houses of worship as the Church of the Transfiguration (the "Little Church Around the Corner"), Trinity Chapel (site of the wedding between writer Edith Newbold Jones and Edward Wharton and now the home of the Serbian Orthodox Cathedral of Saint Sava) and Marble Collegiate Church.[13]

The area became a meeting place for the Gilded Age elite, and a late-nineteenth century mecca for shoppers, tourists and after-theater restaurant patrons. A list of celebrities who ate at Delmonico's is a who’s who of the day, including Diamond Jim Brady, Mark Twain, Jenny Lind, Lillian Russell, Charles Dickens, Oscar Wilde, J.P. Morgan, James Gordon Bennett, Jr., Walter Scott, Edward VII of the United Kingdom (then the Prince of Wales), and Napoleon III of France.

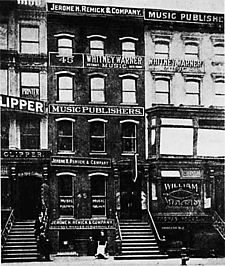

Tin Pan Alley on West 28th Street

Tin Pan Alley on West 28th Street

A commercial boom followed with the growth of hotels, restaurants, entertainment venues and office buildings, many of which are still standing. By the late nineteenth century, business activity began to eclipse the residential scene around the park, and the area along Broadway above the park began to be subsumed into the Tenderloin, an entertainment-and-vice red-light district full of nightclubs, saloons, bordellos, gambling casinos, dance halls and "clip joints". At about this time, on August 14, 1894, the world's first kinetoscope parlor opened in a former shoe store at 1155 Broadway, on the corner of 27th Street. For 25 cents, patrons could stand and watch a short film through a shaded "peephole" on William Dickson's device. The store had 10 of these machines, and netted $120 for its opening day.[14]

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century the area around 28th Street between Fifth Avenue and the Avenue of the Americas (Sixth Avenue) was dubbed Tin Pan Alley thanks to the collection of music publishers and songwriters there who dominated the American commercial music world of the time. Around the same time, the 1913 Armory Show, which took place at the 69th Regiment Armory on Lexington Avenue between 25th and 26th Streets, was a seminal event in the history of Modern Art.

The neighborhood deteriorated somewhat during the mid- and late-twentieth century. Tee-shirt, luggage, perfume and jewelry wholesalers began lining the storefronts along Broadway from Madison Square to Herald Square, and wholesalers continue to dominate that stretch. By the second half of the twentieth century, Madison Square Park was suffering from neglect and petty crime.[15] The massive 2001 park restoration project, spearheaded by the Madison Square Park Conservancy[16] spurred a transformation of the neighborhoods around the park – the Flatiron District, Rose Hill and NoMad – from primarily commercial to places attractive for residences, upscale businesses and trendy restaurants and nightspots.

Notable persons

- Buried under Worth Square at the intersection of Broadway, Fifth Avenue, West 24th and West 25th Street is Mexican War hero Major General William Jenkins Worth, for whom Fort Worth, Texas was named.[9]

- Roscoe Conkling, whose statue stands at the southeast corner of Madison Square Park, was a kingmaker in the Republican Party in the last half of the nineteenth century and is closely associated with the Fifth Avenue Hotel and political scandals during the James A. Garfield and Chester Alan Arthur administrations.

- Stanford White, partner in the respected architectural firm of McKim, Mead and White, designed the magnificent Madison Square Garden, which stood from 1890–1925 between 26th and 27th Streets at Madison Avenue on the north corner of Madison Square Park. Featuring the largest amphitheater in the US, the building’s tower contained White’s apartment and love nest topped by a scantily draped statue of Diana. There, he entertained Evelyn Nesbit Thaw, one of the Garden’s rooftop Floradora Girls. In a jealous rage, her husband, Harry Thaw, shot White in the middle of a musical production on the roof. Six years into the twentieth century, the media was touting the trial of the murderer of Stanford White, one of the country’s most prolific architects and womanizers, as "The Trial of the Century."[17]

- Nikola Tesla, who lived in the Radio Wave Building on 27th Street between Broadway and Sixth, is renowned today as the leading electrical engineer of his time. Tesla developed AC current, the radio, power transmission techniques and the first robotics. His demonstration of remotely controlled boats at Madison Square Garden was a sensation in 1898. The craft alarmed those in the crowd who saw it and who claimed it to be everything from magic and telepathy to being piloted by a trained monkey hidden inside.[18]

Architecture

French Renaissance revivial architectural detail of a building in NoMadThe top of the New York Life Building at nightAmong the notable buildings in the area are New York Life Building, the Gift Building, which has been converted to a luxury condominium, and the Toy Center, which has been converted to an office complex.[19]

Designed in 1904 by Stanford White as the prestigious Colony Club for socialites, the building at 120 Madison Avenue has been occupied since 1963 by the American Academy of Dramatic Arts.[20] Long before the Academy began training its young hopefuls in the NoMad area, the Madison Square Theater opened in 1880. Boasting the first electric footlights and a backstage double-decker elevator, the theater also provided an early air-conditioning system.[21]

Along Broadway, the Townsend (1896) and St. James (1896) were the tallest buildings in New York for a short while, and remain historic landmarks. Slightly up the street, the Baudouine Building at 28th Street was heavily decorated with escutcheons of anthemions with lion heads over many windows. At the same corner, the Johnston Building (soon to be the Hotel NoMad) was built in 1900 and faced in all limestone with beautiful exterior decoration. One block up, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis’s grandfather built a classically designed loft building, next to the Breslin.[22]

Hotels past and present

The Fifth Avenue Hotel in 1860

The Fifth Avenue Hotel in 1860

NoMad was once home to some of New York’s most luxurious hotels, and the area has recently seen the development of new, imaginative boutique hotels.

The luxurious Fifth Avenue Hotel, completed in 1859 by Amos R. Eno, whose gleaming white-marble building, housing 100 apartment suites, contained a few startling firsts, such as private bathrooms, elevators and a fourth meal, or "late supper", and was a popular meeting place for politicians, brokers and speculators. Initially dubbed "Eno’s Folly" for its opulence and location at the far uptown edge of the city – the site had previously been an inn where travellers leaving the city opr returning to it could get a meal or lodging before contuning their trip. The hotel stood between 23rd and 24th Streets facing Madison Square, where the Toy Center South stands today.[23][24]

The Fifth Avenue Hotel stood without serious competition for a decade, but by the 1870s, numerous hotels catering to much the same clientele had opened in the area, including the Hoffman House (24th Street), the Victoria (27th Street), the Gilsey House (29th Street), whose building still stands, the Grand (31st Street), also still standing – both were converted for residential use – and the Brunswick.[25]

The Brunswick, at 26th Street and Fifth Avenue, was the hotel favored by the horsey set.[25] The male-only New York Coaching Club, established in 1875 by Col. Delancey Astor Kane and William Jay, was headquartered there, and elevated "four-in-hand" carriage riding to an art form.[26] Holding the reins of all four horses in one fist, the drivers ("whips") guided their horses from the Brunswick to the carriage drives in Central Park and staged parades twice a year.[27]

The St. James Hotel at Broadway and 26th Street, where the St. James Building now stands, was built in 1874 to accommodate a stylish crowd. With its 30 parlors, bar, cigar stand, barber shop, dining room and full-service amenities, the hotel served the needs of typical mid- to late-nineteenth century business and upscale clientele.

Known since 1987 as the Carlton, the Hotel Seville, named for the original investor Maitland E. Graves’ infatuation with the Spanish city, was designed by Harry Allen Jacobs, and opened its doors on East 29th Street and Madison Avenue in 1904, months before the unveiling of the city’s first subway. Renovated and transformed at a cost of $60 million more than a century later by David Rockwell, the hotel’s "Tiffany-style glass skylight" on the mezzanine was discovered under layers of paint “used to deter air raids during World War II.”[28][29]

The Breslin Hotel, built in 1904, was transformed in 2009 into the Ace Hotel, a 300-room hotel whose restaurant has attracted a trendy crowd.[30] Slated to open in 2011, the NoMaD Hotel at 28th Street and Broadway, will occupy the Johnston Building, a landmark 1900 French Renaissance limestone space.[22][31] The Gershwin Hotel, on East 27th Street, and named after George Gershwin, has a unique facade, a combination of red paint and whimsical decorative touches.

Named for one of New York’s most oldest families, the 19-floor Gansevoort Park, is planned to open at Park Avenue and 29th Street, complete with a "glass column containing light-emitting diodes" that change color.[32] Rounding out the host of boutique hotels in and around NoMad is Hotel Thirty Thirty, aptly located at 30 East 30 Street.

Restaurants

The neighborhood was once the home of Delmonico's, New York elite society's favorite restaurant and the birthplace of Lobster Newburg. Today it has a numerous restaurants serving a wide range of cuisines, including San Rocco, Hill Country Barbecue, Bamiyan Afghan Restaurant, Antique Cafe, SD26, A Voce, Country, Ben & Jack’s Steakhouse and Illi. Eataly, a 44,000-square-foot (4,100 m2) Italian food market comprising Italian restaurants, cafes and wine and food shops opened in Summer 2010.[33]

Culture, art and nightlife

NoMad is home to the Museum of Sex, the New York Comedy Club and Tada! Youth Theater, and is also a center for antique galleries and one of the city’s largest collections of weekend flea markets. Nightspots and clubs include the Breslin Lobby Bar, Jay Z’s 40/40, the rooftop bar at 230 Fifth Avenue, Gstaad, Hillstone’s, and the Park Avenue Country Club.

See also

- Chelsea, Manhattan

- Flatiron District

- Kip's Bay

- Madison Square North Historic District

- Murray Hill

- Rose Hill, Manhattan

Gallery

- Around NoMad

-

The 69th Regiment Armory, completed in 1906, is a National Historic Landmark

-

Marble Collegiate Church (1851-1854); for many years Norman Vincent Peale was its pastor[1]

References

- Notes

- ^ a b c White, Norval & Willensky, Elliot (2000). AIA Guide to New York City (4th ed.). New York: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 0812931076.

- ^ "New York Architecture Images- Gilsey House". Nyc-architecture.com. http://www.nyc-architecture.com/GRP/GRP026.htm. Retrieved 2010-06-06.

- ^ Louie, Elaine (August 5, 1999). "The Trendy Discover NoMad Land, And Move In". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/1999/08/05/garden/the-trendy-discover-nomad-land-and-move-in.html. Retrieved 2010-05-15.

- ^ Feirstein, Sanna (2001). Naming New York: Manhattan Place & How They Got Their Names. New York: New York University Press. p. 103. ISBN 9780814727126.

- ^ Melwani, Lavina (June 12, 2006). "New York! New York!". Little India. http://www.littleindia.com/news/154/ARTICLE/1127/2006-06-12.html. Retrieved 2010-05-15.

- ^ Neighborhoods in New York City do not have official status, and their boundaries are not specifically set by the city. (There are a number of Community Boards, whose boundaries are officially set, but these are fairly large and generally contain a number of neighborhoods and the neighborhood map issued by the Department of City Planning only shows the largest ones, and the neighborhood map issued by the Department of City Planning only shows the largest ones.) Because of this, the definition of where neighborhoods begin and end is subject to a variety of forces, including the efforts of real estate concerns to promote certain areas, the use of neighborhood names in media news reports, and the everyday usage of people. The eastern boundary of NoMad, an up-and-coming negihborhood, and the western boundary of Rose Hill, a revived name for the neighborhood north and east of Madison Square Park, is thus uncertain, and propnents of both may make claim to the assests that lie in the borderlands between them.

- ^ Community Board 5

- ^ Berman, Miriam (2001). Madison Square: The Park and its Celebrated Landmarks. Salt Lake City: Gibbs Smith. p. 9. ISBN 1586850377.

- ^ a b Feirstein, Sanna (2001). Naming New York: Manhattan Place & How They Got Their Names. New York: New York University Press. p. 106. ISBN 9780814727126.

- ^ Mendelsohn, p.26

- ^ Mendelsohn, p.15

- ^ Jim Naureckas (1920-04-03). "Madison Avenue: New York Songlines". Nysonglines.com. http://www.nysonglines.com/madison.htm. Retrieved 2010-06-06.

- ^ Tarver, Denton (June 2006). "From Farmland to High Rises". The Cooperator. http://www.cooperator.com/articles/1293/1/From-Farmland-to-High-Rises/Page1.html. Retrieved 2010-05-15.

- ^ Alexiou, Alice Sparberg. The Flatiron: the New York landmark and the incomparable city that arose with it. New York: Thomas Dunne/St. Martin's, 2010. ISBN 978-0-312-38468-5, p.130

- ^ Sternbergh, Adam (April 11, 2010). "Soho. Nolita. Dumbo. NoMad?". New York. http://nymag.com/realestate/neighborhoods/2010/65365/. Retrieved 2010-05-15.

- ^ https://www.madisonsquarepark.org/Home/Default.aspx

- ^ "New York Architecture Images- Madison Square Garden". Nyc-architecture.com. http://www.nyc-architecture.com/GON/GON016.htm. Retrieved 2010-06-06.

- ^ Eger, Christopher (April 1, 2007) "The Robot Boat of Nikola Tesla: The Beginnings of the UUV and remote control weapons"

- ^ Gregor, Alison (March 1, 2005). "Commercial Madison Square Park Going Condo". The Real Deal. http://therealdeal.com/newyork/articles/commercial-madison-square-park-going-condo. Retrieved 2010-05-15.

- ^ "New York Architecture Images- Colony Club". Nyc-architecture.com. http://www.nyc-architecture.com/UES/UES015.htm. Retrieved 2010-06-06.

- ^ "Madison Square Theatre". Wayneturney.20m.com. http://www.wayneturney.20m.com/madisonsquaretheatre.htm. Retrieved 2010-06-06.

- ^ a b Gray, Christopher (February 10, 2010). "A Hip Replacement for a Down-at-the-Heels ’Hood". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/14/realestate/14streets.html. Retrieved 2010-05-15.

- ^ Morris, Lloyd (1951) Incredible New York; high life and low life from 1850 to 1950. Wakefield, MA.: The Murray Printing Company, pp. 6-7. ISBN 0815603347

- ^ "The Fifth-Avenue Hotel". The New York Times: p. 4. August 23, 1859. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=9D04E2D81F31EE34BC4B51DFBE668382649FDE. Retrieved 2010-05-21.

- ^ a b {[cite gotham}}, 9.959

- ^ "The Carriage Era in New York". Antiquesandthearts.com. http://antiquesandthearts.com/archive/era.htm. Retrieved 2010-06-06.

- ^ "Flatiron Flashbacks". Flatiron 23rd Street Partnership. http://www.flatironbid.org/flashback. Retrieved 2010-05-21.

- ^ "Our Story". The Carlton Hotel. http://www.carltonhotelny.com/hotel/Hotel_History.html. Retrieved 2010-05-21.

- ^ "A Brief History of New York's Quintessential Madison Avenue Landmark" (PDF) (Press release). The Carlton Hotel. July 2009. http://www.carltonhotelny.com/data/uploads/TheCarlton_Hotel_History.pdf. Retrieved 2010-05-21.

- ^ Bernstein, Fred A. (September 27, 2009). "Ace Hotel, New York". The New York Times. http://travel.nytimes.com/2009/09/27/travel/27checkin.html. Retrieved 2010-05-15.

- ^ NoMaD Hotel website

- ^ Hughes, C.J. (August 22, 2007). "Counting on a Hotel to Make a Neighborhood Hot". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2007/08/22/realestate/commercial/22hotel.html. Retrieved 2010-05-15.

- ^ "L&L Leases 40,000 s/f Retail Showpiece to Italian Phenom". Real Estate Weekly: p. 11. July 22, 2009. http://www.ll-holding.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=45&Itemid=4&nid=128&gid=1. Retrieved 2010-05-15.[dead link]

- Bibliography

- Mendelsohn, Joyce. Touring the Flatiron. New York: New York Landmarks Conservancy, 1998. ISBN 0-964-7061-2-1

External links

- Madison Square Park News

- "Madison Square North Historic District Designation Report" of the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission

Categories:- Neighborhoods in Manhattan

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.