- Economic history of modern China

-

For developments before 1911, see Economic history of China (Pre-1911). For economic history since 1949, see Economy of the People's Republic of China.

The economic history of modern China began with the fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1911. Following the Qing, China underwent a period of instability and disrupted economic activity. Under the Nanjing decade (1927–1937), China advanced several industries, in particular those related to the military, in an effort to catch up with the west and prepare for war with Japan. The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) and the following Chinese civil war caused the collapse of the Republic of China and formation of the People's Republic of China.[1]

The new ruler of China, Mao Zedong, initially promised to develop "a socialist alliance with petit-bourgeois, workers, and nationalist bourgeois", but enacted collectivization upon consolidation of this regime. Collectivization resulted in the success of the first five-year plan, but Mao's second five-year plan, which included the Great Leap forward, did not meet with the same success. A new party faction who supported private plots eventually challenged Mao's economic policy. Unwilling to give up power, Mao launched the Cultural Revolution, which led to the collapse of the Chinese economy.

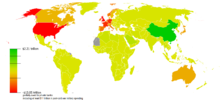

Following Mao's death, one of the most senior officials who had advocated private plots in the early 1960s, Deng Xiaoping, initiated gradual market reforms that abolished the communes and collectivized industries of Mao, replacing them with the free-market system. Deng's reforms vastly improved the standard of living of the Chinese people, the competitiveness of the Chinese economy, and caused China to become one of the fastest growing and most important economies in the world. It also led to one of the most rapid industrializations in world history. For this achievement he is sometimes known as "The Venerated Deng" (Chinese:邓公). As a result of Deng's reforms, China is widely regarded as a returning superpower.

By mid-2000s China had become the second largest economy in the world by GDP (PPP), while in the early 2011 it was confirmed that China surpassed Japan by nominal GDP.[2] At the end of 2010, Japan had GDP worth $5.474 trillion (£3.414 trillion). At the same time, China's GDP was around $5.8 trillion.[2] According to one source, if the current relative growth rates persist, in about 10 years China will be at rough parity with the USA by any type of GDP measure.[2]

Republic of China (1911-1949)

The Republic of China was a period of turmoil for China after the collapse of the Qing dynasty. From 1911 to 1927, China virtually disintegrated into regional warlords, fighting for authority and causing economic misery and contraction. After 1927, Chiang Kai-shek managed to reunify China and bring in the Nanjing decade, a period of relative prosperity despite civil war and Japanese aggression. In 1937, the Japanese invaded and literally laid China to waste in eight years of war. The era also saw the first boycott of Japanese products. Afterwards, the Chinese civil war further devastated China and led to the fall of the Republic in 1949.

Civil war, famine and turmoil in the early republic

The early republic was marked by frequent wars and factional struggles. From 1911 to 1927, famine, war and change of government was the norm in Chinese politics, with provinces periodically declaring "independence". The collapse of central authority caused the economic contraction that was in place since Qing to speed up, and was only reversed when Chiang reunified China in 1927 and proclaimed himself its leader[3].

Development of domestic industries

Chinese domestic industries developed rapidly after the downfall of the Manchu Qing dynasty, despite turmoil in Chinese politics. Development of these industries peaked during World War I, which saw a great increase in demand for Chinese goods, which benefitted China's industries. In addition, imports to China fell drastically after total war broke out in Europe. For example, China's textile industry had 482,192 needle machines in 1913, while by 1918 (the end of the war) that number had gone up to 647,570. The number increased even faster to 1,248,282 by 1921. In addition, bread factories went up from 57 to 131[4].

The May 4th movement, in which Chinese students called China's population to boycott foreign goods, also helped spur development. Foreign imports fell drastically from 1919–1921 and from 1925 to 1927.[5]

Chinese industries continue to develop in the 1930s with the advent of the Nanking decade in the 1930s, when Chiang Kai-shek unified most of the country and brought political stability. China's industries developed and grew from 1927 to 1931. Though badly hit by the Great Depression from 1931 to 1935 and Japan's occupation of Manchuria in 1931, industrial output recovered by 1936. By 1936, industrial output had recovered and surpassed its previous peak in 1931 prior to the Great Depression's effects on China. This is best shown by the trends in Chinese GDP. In 1932, China's GDP peaked at 28.8 billion, before falling to 21.3 billion by 1934 and recovering to 23.7 billion by 1935.[6]

The rural economy of the Republic of China

The rural economy retained much of the characteristics of the Late Qing. While markets had been forming since the Song and Ming dynasties, Chinese agriculture by the Republic of China was almost completely geared towards producing cash crops for foreign consumption, and was thus subject to the say of the international markets. Key exports included glue, tea, silk, sugar cane, tobacco, cotton, corn and peanuts.[7]

The rural economy was hit hard by the Great Depression of the 1930s, in which an overproduction of agricultural goods lead to massive falling prices for China as well as an increase in foreign imports (as agricultural goods produced in western countries were "dumped" in China). In 1931, imports of rice in China amounted to 21 million bushels compared with 12 million in 1928. Other goods saw even more staggering increases. In 1932, 15 million bushels of grain were imported compared with 900,000 in 1928. This increased competition lead to a massive decline in Chinese agricultural prices (which were cheaper) and thus the income of rural farmers. In 1932, agricultural prices were 41 percent of 1921 levels.[8]. Rural incomes had fallen to 57 percent of 1931 levels by 1934 in some areas[8].

Foreign direct investment in the Republic of China

Foreign direct investment in China soared during the Republic of China. Some 1.5 billion of investment was present in China by the beginning of the 20th century, with Russia, The United Kingdom and Germany being the largest investors. However, with the outbreak of WWI, investment from Germany and Russia stopped while England and Japan took a leading role. By 1930, foreign investment in China totalled 3.5 billion, with Japan leading (1.4 billion) and England at 1 billion. By 1948, however, the capital stock had halted with investment dropping to only 3 billion, with the US and Britain leading[9].

Currency of the Republic of China

The currency of China was initially silver-backed, but the nationalist government seized control of private banks in the notorious banking coup of 1935 and replaced the currency with the Fabi, a fiat currency issued by the ROC. Particular effort was made by the ROC government to instill this currency as the monopoly currency of China, stamping out earlier Silver and gold-backed notes that had made up China's currency. Unfortunately, the ROC government used this privilege to issue currency en masse; a total of 1.4 billion Chinese yuan was issued in 1936, but by the end of the second Sino-Japanese war some 1.031 trillion in notes was issued[10]. This trend worsened with the outbreak of the Chinese Civil war in 1946. By 1947, some 33.2 trillion of currency was issued as a result of massive budget deficits resulting from war (taxation revenue was just 0.25 billion, compared with 2500 billion in war expenses). By 1949, the total currency in circulation was 120 billion times more than in 1936.[11].

The Chinese war economy (1937-1945)

In 1937, Japan invaded China and the resulting warfare literally laid waste to China. Most of the prosperous east China coast was occupied by the Japanese, who carried out various atrocities such as the Rape of Nanjing in 1937 and random massacres of whole villages. In one anti-guerilla sweep in 1942, the Japanese killed up to 200,000 civilians in a month. The war was estimated to have killed between 20 and 25 million Chinese, and destroyed literally all that Chiang had built up in the preceding decade[12]. Development of industries was severely hampered after the war by devastating conflict as well as the inflow of cheap American goods. By 1946, Chinese industries operated at 20% capacity and had 25% of the output of pre-war China[13].

One effect of the war was a massive increase in government control of industries. In 1936, government-owned industries were only 15% of GDP. However, the ROC government took control of many industries in order to fight the war. In 1938, the ROC established a commission for industries and mines to control and supervise firms, as well as instilling price controls. By 1942, 70% of the capital of Chinese industry were owned by the government[14].

Hyperinflation, civil war and the relocation of the republic to Taiwan

Following the war with Japan, Chiang acquired Taiwan from Japan and renewed his struggle with the communists. However, the corruption of the KMT, as well as hyperinflation as a result of trying to fight the civil war, resulted in mass unrest throughout the Republic[15] and sympathy for the communists. In addition, the communists' promise to redistribute land gained them support among the massive rural population. In 1949, the communists captured Beijing and later Nanjing as well. The People's Republic of China was proclaimed on 1 October 1949. The Republic of China relocated to Taiwan where Japan had laid an educational groundwork.[16] Taiwan continued to prosper under the Republic of China government and came to be known as one of the Four Asian Tigers due to its "economic miracle", and later became one of the largest sources of investment in mainland China after the PRC economy began its rapid growth following Deng's reforms.[17]

People's Republic of China (1949 onwards)

Main article: Economic history of the People's Republic of China A 1950 postage stamp of Mao Zedong, Chairman of the Communist Party of China, shaking hands with Joseph Stalin, General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

A 1950 postage stamp of Mao Zedong, Chairman of the Communist Party of China, shaking hands with Joseph Stalin, General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The People's Republic of China is marked by two distinctly different periods: the Mao Era, characterized by a soviet-style planned economy that extinguished the market and eventually became unresponsive, and the post-Mao Era, more properly called the Deng Era (after the reformer who started it) characterized by a transition to a relatively free market economy which was one of the most prosperous periods in China's history. Many Chinese are hopeful that this newfound prosperity will last and China will reclaim her place at the top of nations.

The Mao Era (1949-1976)

The Mao Era was marked by a soviet-style planned economy which was instituted, despite his promises, in 1949-52. A decade of relatively peaceful development and collectivization followed, but in 1959 Mao launched the disastrous Great Leap forward, an attempt to collectivize all aspects of life (even the peasants' cooking pots), a disaster that was exacerbated by famine. Following this, a reformist faction led by Deng Xiaoping and Liu Shaoqi forced Mao out of office and experimented with market reforms such as giving peasants private plots. However, these reform efforts were disrupted by Mao's Cultural Revolution, a period of virtually total anarchy and street fighting(武鬥) that resulted in the collapse of the Chinese economy and ended with the arrest of the Gang of Four.

Early policies of tolerance

Mao initially promised to work with "patriotic capitalists, the petit-bourgeois and other classes" in a period of "New Democracy" in which some capitalism would be allowed. However, in 1952 he broke his promise and accused capitalists of sabotaging China's war effort in Korea. Following this, businesses were collectivized(國有化)[18].

Collectivization of industry and agriculture

Collectivization of industry took place from 1951 to 1954, by which time industry was entirely in state hands. Despite the communist party's original plans not to finish collectivization of agriculture until 1971, Mao pushed ahead with mutual aid teams by 1953, and People's commune (人民公社) by 1955, forcing the collectivization of agriculture.

Economic development in the 1950s

With Soviet aid, Mao set up a basic industrial base that included a small set of industries, mostly related to military matters, that was to become the basis of the later modernization by Deng Xiaoping. New buildings, roads, railroads, and a basic infrastructure was put in place to sustain Chinese development. Illiteracy and a whole host of parasites were eradicated. For these reasons, the 1950s is usually regarded as the high point of the Mao Era.

Great Leap Forward

The progression of China’s economy is broken down into two different processes. The first step to China’s growth involved improving agriculture, foreign investment, and the birth of entrepreneurs. In the late 1970s, food production and supplies became so scarce that the Chinese people were scared to relive the famine that swept away millions of people in 1959. The government officials mandated more of an individualized farming rather than communal plotting. This move “increased agricultural production, increased the living standards of hundreds of millions of farmers and stimulated rural industry” (CBC News). The second stage to China’s economic growth involved privatization of state-owned industry and rise of price controls. China’s private sector grew so immensely that it was accounted for “over 70% of China’s GDP in 2005” (CBC News).

In 1959, Mao launched a crash industrialization program under the official title the Great Leap forward. This involved making many peasants urban workers, collectivizing virtually everything (including cooking tools) and setting up backyard furnaces to improve steel production. However, the program was a disastrous failure[19]. The new collectivization destroyed the incentive of the peasants, and distorted priorities. Most of the new steel produced from backyard furnaces was useless. The food system collapsed and millions—estimated to have been as high as 45 million—people died, usually from starvation or vulnerability to disease caused by severe malnutrition.[20]

Attempts at reform

China’s open economy is defined after 1978 when economic reforms were started within the Communist Party of China. Ever since China’s economy opened, the transformation positively affected not only china, but the whole world. The last several decades record the history of one of the fastest reduction of poverty and growth of income, simultaneously.

Reformists, such as Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping, began to push for reform, after the disastrous Great Leap Forward. They undid some of Mao's priorities, such as disbanding the People's communes and giving peasants private plots. Mao was infuriated and, in 1966, struck against the reformers, calling them Capitalist roaders and launching the Cultural Revolution.[21]

Cultural Revolution and collapse of the economy

The Cultural Revolution party program is almost universally assessed to bring about one of the most catastrophic periods ever in China.[citation needed] Youth groups aligned with Mao, known as Red Guards, deposed, brutalised and frequently executed city and provincial government officials, and then took control themselves. This began in Shanghai and quickly spread across the country. By 1966, most of the country was in the hands of revolutionary committees which battled each other for power.[21]

This disruption, as well as the purge of millions of intellectuals, workers, and officials as counter-revolutionaries, had a severe impact on the economy.[21] Economic output fell some 30% over three years, and stagnated for the rest of the period. In addition, an entire generation was deprived of education while China's development was hampered for years to come. Referring to this period, Deng Xiaoping said it had created "an entire generation of mental cripples".

Deng Xiaoping's rise

An old party stalwart, Deng had been of the reformist faction in the early 1960s and purged in the Cultural Revolution. After Mao's death, however, a coup overthrew the Gang of Four and instilled old party officials such as Deng back in power. However, it was not until 1978 that Hua Guofeng, Mao's appointed successor, resigned and Deng took power, though he was never officially the leader, instead holding the position of chairman of the Central military commission.

From planned economy to free market powerhouse: The post-Mao Era (1976 onwards)

Main article: Chinese economic reformWhile, in 1976, at the end of the Cultural Revolution, China's planned economy was in ruins and its people barely surviving, the country was to witness, in the next two years, one of the most rapid periods of change in her 5,000-year history. Deng Xiaoping initiated free-market reforms that transformed China's economy.[22] Only 30 years later, China moved from being an economically desolate country into an industrial powerhouse, rapidly overtaking developed western nations in recession.[22] The agent of this dramatic change, Deng Xiaoping, is sometimes known as "Deng Gong" (The Venerated Deng) for his achievements.

De-collectivization of agriculture

One of Deng's first actions was to break up the People's communes that Mao instated and grant a system of "Bao Chang Dao Hu" (包產到户), in which each plot of land was given to each household to farm. This system was successful enough to allow Deng in 1983 to lift limits on consumption of many agricultural goods that were instated during the Mao Era due to scarcity. However, these limits were not completely lifted until 1994[23].

Liberalization and privatization of business

A Shanghai branch of Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, largest in the world.

A Shanghai branch of Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, largest in the world. See also: Chengbao system

See also: Chengbao systemPrivate businesses, which were banned in the Mao Era for being "Capitalist exploiters”, were reinstated in the Deng Era. Early on, a citizen could opt to become "Ge Ti Hu"(個体户) or self-employed household, and to set up a business instead of taking on state jobs. These "Ge Ti Hu" quickly became extremely wealthy. In the 1990s, many state enterprises were privatized and private individuals were allowed to create companies. In 1990, the Shanghai Stock Exchange was reopened after Mao first closed it 41 years earlier.

Another innovation instated during this period was the Chengbao system[24] or contracting system, in which state assets were given to private operators, who gave the state the money needed for expenses as well as a share of the profits. This system was also rapidly adopted; in the 1980s and 1990s, many schools, hospitals and even bus lines passed from the state to private operators. However, this system was also criticized as many felt that the change in operation for these schools and hospitals, now for-profit, was detrimental to the poor. In addition, some private contractors were accused of gaining their positions solely because of nepotism.

Although privatizations had occurred in the 1980s, it was sped up in the 1990s by Premier Zhu Rongji, who started a policy of privatizing all state enterprises which were losing money. In 1997, the CPC issued a verdict declaring that state-owned companies were now "people-owned companies" who would be subject to mergers and bankruptcy. Thousands of state companies were privatized or partly floated on the stock exchange. In 1978, more than 90% of GDP was produced in state enterprises, which, up to 1992, dominated China's economy. That figure, not accounting for state assets that were contracted, had fallen to 30% by 2009.

Foreign investment and industrialization

In addition to internal liberalization, Deng also established a series of "special economic zones" in which foreigners could invest in China taking advantage of lower labor costs. This investment helped the Chinese economy boom. In addition, the Chinese government established a series of joint ventures with foreign capital to establish companies in industries hitherto unknown in China. By 2001, China became a member of the World Trade Organization, which has boosted its overall trade in exports/imports—estimated at $851 billion in 2003—by an additional $170 billion a year.[25]

Despite a brief period in 1989 in which foreign capital withdrew from China, China continued to be one of the biggest recipients of foreign investment[26]. In 2006, an estimated $699.5 billion of foreign investment was present in China. A great deal of this investment came from Chinese-speaking regions such as Hong Kong and Taiwan, who were the first to invest in China. Japanese and Western investment followed.

Deng's liberalization of the Chinese economy, along with foreign investment, helped to power China's industrialization. From virtually an industrial backwater in 1978, China is now the world's biggest producer of concrete, steel, ships, textiles as well as the world's biggest auto market. For example, from 2000 to 2006, China's steel production rose from 140 million tons to 416 million tons[27]. From 1975 to 1992, China's auto production rose from 139,800 to 1.1 million automobiles before jumping to 9.35 million in 2008[28].

Developments post-Deng

In 1997, Deng Xiaoping died. However, his reformist policies were continued by his successor, Jiang Zemin. The result was a vibrant, growing economy.

Under Hu and Wen, who became leaders of China in 2003, the Chinese government continued to give up grounds to private enterprise, yet increased its control in other areas. The new premier, Wen Jiabao, reinstated some Mao-Era social systems, such as social security, as well as sponsoring a new initiative in health care in which the state retook control of hospitals from many contractors who had run them for two decades. However, this was reversed in 2009. Nevertheless, China's economy continued to grow. In 2008, however, it was affected by the global financial meltdown and the growth rate fell to 9.0%. As of 2008, China's GDP (PPP) was between 50 and 60 percent of the GDP (PPP) of the US, while over 10 percent of world GDP (PPP).

To offset the effects of the global economic crisis, the government announced a financial stimulus of around 4 trillion yuan spread over two years. However, new spending by the government was actually only about 1 trillion yuan; the rest was already part of the government's budget.[29]

In mid-2005, China began to experience an enormous property bubble, largely caused by loose monetary policy under premier Wen Jiabao. Property prices tripled from 2005 to 2009, and are continuing to rise[30].

Some analysts also discovered a new management style in China. The Chinese managers refrain from the American management model, where short-dated success are more important than long-dated strategies, and take more care of the environment, the people and the culture of an area, where they do business.[31]

World's second largest economy

In July 2010, Yi Gang, Deputy Governor of the Bank of China, claimed China's economy had overtaken Japan as the world's second biggest economy by nominal GDP.[32] This fact was confirmed in February 2011, when the official economic statistics was issued by Japan (Chinese statistics for 2010 was published earlier), which showed that Japan's 2010 GDP was worth $5.474 trillion, when China's 2010 GDP was around $5.8 trillion.[2]

See also

- Economy of the Han Dynasty

- Economy of Hong Kong

- Economy of the Song Dynasty

- Economic history of China (Pre-1911)

- Economy of Macau

- Economy of the Ming Dynasty

- Economic history of the People's Republic of China

- Economy of the People's Republic of China

- Economy of Taiwan

Further reading

- Fengbo Zhang : Analysis of Chinese Macroeconomy .

- Chow, Gregory C. China's Economic Transformation (2nd ed. 2007) excerpt and text search

- Duara, Prasenjit, State Involution: A Study of Local Finances in North China, 1911-1935, in Comparative Studies in Society and History, Vol. 29, No. 1 (Jan., 1987), pp. 132–161, Cambridge University Press

- Eastman Lloyd et al. The Nationalist Era in China, 1927-1949 (1991) excerpt and text search

- Fairbank, John K., ed. The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 12, Republican China 1912-1949. Part 1. (1983). 1001 pp., the standard history, by numerous scholars

- Fairbank, John K. and Feuerwerker, Albert, eds. The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 13: Republican China, 1912–1949, Part 2. (1986). 1092 pp., the standard history, by numerous scholars

- Ji, Zhaojin. A History of Modern Shanghai Banking: The Rise and Decline of China's Finance Capitalism. (2003. 325) pp.

- MacFarquhar, Roderick and Fairbank, John K., eds. The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 15: The People's Republic, Part 2: Revolutions within the Chinese Revolution, 1966-1982. Cambridge U. Press, 1992. 1108 pp.

- Naughton, Barry. The Chinese Economy: Transitions and Growth (2007)

- Rawski, Thomas G. and Lillian M. Li, eds. Chinese History in Economic Perspective, University of California Press, 1992 complete text online free

- Rubinstein, Murray A., ed. Taiwan: A New History (2006), 560pp

- Sheehan, Jackie. Chinese Workers: A New History. Routledge, 1998. 269 pp.

- Shiroyama, Tomoko. China during the Great Depression: Market, State, and the World Economy, 1929-1937 (2008)

- Young, Arthur Nichols. China's nation-building effort, 1927-1937: the financial and economic record (1971) 553 pages full text online

References

- ^ Sun Jian, page 616-618

- ^ a b c d BBC: China overtakes Japan as world's second-biggest economy

- ^ Sun Jian, page 613-614

- ^ Sun Jian, page 894-895

- ^ Sun Jian, page 897

- ^ Sun Jian, pg 1059-1071

- ^ Sun Jian, page 934-935

- ^ a b Sun Jian, page 1089

- ^ Sun Jian, pg 1353

- ^ Sun Jian, pg 1234-1236

- ^ Sun Jian, page 1317

- ^ Sun Jian, page 615-616

- ^ Sun Jian, page 1319

- ^ Sun Jian, pg 1237-1240

- ^ Sun Jian, page 617-618

- ^ Gary Marvin Davison. A short history of Taiwan: the case for independence. Praeger Publishers. p. 64. ISBN 0-275-98131-2. "Basic literacy came to most of the school-aged populace by the end of the Japanese tenure on Taiwan. School attendance for Taiwanese children rose steadily throughout the Japanese era, from 3.8 percent in 1904 to 13.1 percent in 1917; 25.1 percent in 1920; 41.5 percent in 1935; 57.6 percent in 1940; and 71.3 percent in 1943."

- ^ Top 10 Origins of FDI US-China Business Council, February 2007

- ^ Zhou Enlai: Twenty years since the building of the nation, Ch.1.

- ^ Chan, Alfred (2001), Mao's Crusade: Politics and Policy Implementation in China's Great Leap Forward, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0199244065

- ^ Frank Dikötter, Mao's Great Famine: The History of China's Most Devastating Catastrophe (2010) pp. 91, 146-64, 209, 292

- ^ a b c William A. Joseph (Editor), Christine P.W. Wong (Editor), David Zweig (Editor) (1991). New Perspectives on the Cultural Revolution. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674617584

- ^ a b Donald and Benewick (2005), pg 13.

- ^ China's Great Transformation

- ^ www.chinca.org

- ^ Donald and Benewick (2005), pg 14, 33.

- ^ Foreign investment in China rebounds - International Herald Tribune

- ^ Output of Major Industrial Products AllCountries.org

- ^ 8:47 p.m. ET (2009-02-04). "China poised to be world’s largest auto market - Autos- msnbc.com". MSNBC. http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/29022484/. Retrieved on 2009-04-28.

- ^ Barboza, David (2008-11-10). "China Unveils Sweeping Plan for Economy". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/11/10/world/asia/10china.html.

- ^ Chovanec, Patrick (2009-06-08). "China's Real Estate Riddle". Far East Economic Review. http://www.feer.com/economics/2009/june53/Chinas-Real-Estate-Riddle. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ^ Charles-Edouard Bouée: China's Management Revolution - Spirit, Land, Energy, Palgrave Macmillan, New York 2010, ISBN 978-0-230-28545-3.

- ^ "China Overtakes Japan As No. 2" Business World, 7 August 2010

Sources

- Brandt, Loren et al., China's Great Transformation, ISBN 978-0-511-39680-9 (ebook), April 2008

- Sun, Jian, (Chinese) Economic history of China, Vol 2 (1840–1949), China People's University Press, ISBN 7300029531, 2000.

- Zhou, Enlai: Twenty years since the building of the nation, Ch.1.

- Spence, Jonathan D. (1999). The Search For Modern China. Second Edition. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-97351-4 (Paperback).

- Donald, Stephanie Hemelryk and Robert Benewick. (2005). The State of China Atlas: Mapping the World's Fastest Growing Economy. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press. ISBN 0520246276.

- Chan, Alfred (2001). Mao's Crusade: Politics and Policy Implementation in China's Great Leap Forward. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199244065.

External links

Economic history of China Economic history of China (pre-1911) Economic history of Modern China People's Republic of China · Industralization · Economic Reform · Technological and industrial history ·

Economy of TaiwanCategories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.