- Old English grammar

-

This article is part of a series on:

Old EnglishDialects- Kentish

- Mercian

- Northumbrian

- West Saxon

Use- Orthography

- (Runic alphabet · Latin alphabet)

- Grammar

- Phonology

LiteratureHistory- History of English

- Development of Old English

- (Influences: Germanic · Latin · Old Norse)

The grammar of Old English is quite different from that of Modern English, predominantly by being much more highly inflected, similar to Latin. As an old Germanic language, Old English's morphological system is similar to that of the hypothetical Proto-Germanic reconstruction, retaining many of the inflections theorized to have been common in Proto-Indo-European and also including characteristically Germanic constructions such as umlaut.

Among living languages, Old English morphology most closely resembles that of modern Icelandic, which is among the most conservative of the Germanic languages; to a lesser extent, the Old English inflectional system is similar to that of modern High German.

Nouns, pronouns, adjectives and determiners were fully inflected with five grammatical cases (nominative, accusative, genitive, dative, and instrumental), two grammatical numbers (singular and plural) and three grammatical genders (masculine, feminine, and neuter). First and second person personal pronouns also had dual forms for referring to groups of two people, in addition to the usual singular and plural forms.[1] The instrumental case was somewhat rare and occurred only in the masculine and neuter singular; it could typically be replaced by the dative. Adjectives, pronouns and (sometimes) participles agreed with their antecedent nouns in case, number and gender. Finite verbs agreed with their subject in person and number.

Nouns came in numerous declensions (with deep parallels in Latin, Ancient Greek and Sanskrit). Verbs came in nine main conjugations (seven strong and two weak), each with numerous subtypes, as well as a few additional smaller conjugations and a handful of irregular verbs. The main difference from other ancient Indo-European languages, such as Latin, is that verbs can be conjugated in only two tenses (vs. the six "tenses" – really tense/aspect combinations – of Latin), and have no synthetic passive voice (although it did still exist in Gothic).

Note that gender in nouns was grammatical, as opposed to the natural gender that prevails in modern English. That is, the grammatical gender of a given noun did not necessarily correspond its natural gender, even for nouns referring to people. For example, sēo sunne (the Sun) was feminine, se mōna (the Moon) was masculine, and þæt wīf "the woman/wife" was neuter. (Compare modern German die Sonne, der Mond, das Weib.) Pronominal usage could reflect either natural or grammatical gender, when it conflicted.

Contents

Morphology

Verbs

Verbs in Old English are divided into strong or weak verbs. Strong verbs indicate tense by a change in the quality of a vowel, while weak verbs indicate tense by the addition of an ending.

Strong verbs

Further information: Germanic strong verbStrong verbs use the Germanic form of conjugation known as ablaut. In this form of conjugation, the stem of the word changes to indicate the tense. Verbs like this persist in modern English, for example sing, sang, sung is a strong verb, as are swim, swam, swum and choose, chose, chosen. The root portion of the word changes rather than its ending. In Old English, there were seven major classes of strong verb; each class has its own pattern of stem changes. Learning these is often a challenge for students of the language, though English speakers may see connections between the old verb classes and their modern forms.

The classes had the following distinguishing features to their infinitive stems:

- ī + 1 consonant.

- ēo or ū + 1 consonant.

- Originally e + 2 consonants. By the time of written Old English, many had changed. If we use C to represent any consonant, verbs in this class usually had short e + lC; short eo + rC; short i + nC/mC; or (g̣ +) short ie + lC.

- e + 1 consonant (usually l or r, plus the verb brecan 'to break').

- e + 1 consonant (usually a stop or a fricative).

- a + 1 consonant.

- Other than the above. Always a heavy root syllable (either a long vowel or short + 2 consonants), almost always a non-umlauted vowel – e.g. ō, ā, ēa, a (+ nC), ea (+ lC/rC), occ. ǣ (the latter with past in ē instead of normal ēo). Infinitive distinguishable from class 1 weak verbs by non-umlauted root vowel; from class 2 weak verbs by lack of suffix -ian. First and second preterite have identical stems, usually in ēo (occ. ē), and the infinitive and the past participle also have the same stem.

Stem Changes in Strong Verbs Class Root Weight Infinitive First Preterite Second Preterite Past Participle I heavy ī ā i i II heavy ēo or ū ēa u o III heavy see table below IV light e(+r/l) æ ǣ o V light e(+other) æ ǣ e VI light a ō ō a VII heavy ō, ā, ēa, a(+nC), ea(+rC/lC), occ. ǣ ē or ēo same as infinitive The first preterite stem is used in the preterite, for the first and third persons singular. The second preterite stem is used for second person singular, and all persons in the plural (as well as the preterite subjunctive). Strong verbs also exhibit i-mutation of the stem in the second and third persons singular in the present tense.

The third class went through so many sound changes that it was barely recognisable as a single class. The first was a process called 'breaking'. Before <h>, and <r> + another consonant, <æ> turned into <ea>, and <e> to <eo>. Also, before <l> + another consonant, the same happened to <æ>, but <e> remained unchanged (except before combination <lh>).

The second sound-change to affect it was the influence of palatal sounds <g>, <c>, and <sc>. These turned anteceding <e> and <æ> to <ie> and <ea>, respectively.

The third sound change turned <e> to <i>, <æ> to <a>, and <o> to <u> before nasals.

Altogether, this split the third class into five sub-classes:

- e + two consonants (apart from clusters beginning with l).

- eo + r or h + another consonant.

- e + l + another consonant.

- g, c, or sc + ie + two consonants.

- i + nasal + another consonant.

Stem Changes in Class III Sub-class Infinitive First Preterite Second Preterite Past Participle a e æ u o b eo ea u o c e ea u o d ie ea u o e i a u u Regular strong verbs were all conjugated roughly the same, with the main differences being in the stem vowel. Thus stelan 'to steal' represents the strong verb conjugation paradigm.

Conjugation Pronoun 'steal' Infinitives stelan tō stelanne Present Indicative ic stele þū stilst hē/hit/hēo stilð wē/gē/hīe stelaþ Past Indicative ic stæl þū stæle hē/hit/hēo stæl wē/gē/hīe stælon Present Subjunctive ic/þū/hē/hit/hēo stele wē/gē/hīe stelen Past Subjunctive ic/þū/hē/hit/hēo stǣle wē/gē/hīe stǣlen Imperative Singular stel Plural stelaþ Present Participle stelende Past Participle stolen Weak verbs

Further information: Germanic weak verbWeak verbs are formed by adding alveolar (t or d) endings to the stem for the past and past-participle tenses. Some examples are love, loved or look, looked.

Originally, the weak ending was used to form the preterite of informal, noun-derived verbs such as often emerge in conversation and which have no established system of stem-change. By nature, these verbs were almost always transitive, and even today, most weak verbs are transitive verbs formed in the same way. However, as English came into contact with non-Germanic languages, it invariably borrowed useful verbs which lacked established stem-change patterns. Rather than invent and standardize new classes or learn foreign conjugations, English speakers simply applied the weak ending to the foreign bases.

The linguistic trends of borrowing foreign verbs and verbalizing nouns have greatly increased the number of weak verbs over the last 1,200 years. Some verbs that were originally strong (for example help, holp, holpen) have become weak by analogy; most foreign verbs are adopted as weak verbs; and when verbs are made from nouns (for example "to scroll" or "to water") the resulting verb is weak. Additionally, conjugation of weak verbs is easier to teach, since there are fewer classes of variation. In combination, these factors have drastically increased the number of weak verbs, so that in modern English weak verbs are the most numerous and productive form (although occasionally a weak verb may turn into a strong verb through the process of analogy, such as sneak (originally only a noun), where snuck is an analogical formation rather than a survival from Old English).

There are three major classes of weak verbs in Old English. The first class displays i-mutation in the root, and the second class none. There is also a third class explained below.

Class-one verbs with short roots exhibit gemination of the final stem consonant in certain forms. With verbs in <r> this appears as <ri> or <rg>, where <i> and <g> are pronounced [j]. Geminated <f> appears as <bb>, and that of <g> appears as <cg>. Class one verbs may receive an epenthetic vowel before endings beginning in a consonant.

Where class-one verbs have gemination, class-two verbs have <i> or <ig>, which is a separate syllable pronounced [i]. All class-two verbs have an epenthetic vowel, which appears as <a> or <o>.

In the following table, three verbs are conjugated. Swebban 'to put to sleep' is a class one verb exhibiting gemination and an epenthetic vowel. Hǣlan 'to heal' is a class-one verb exhibiting neither gemination nor an epenthetic vowel. Sīðian 'to journey' is a class-two verb.

Conjugation Pronoun 'put to sleep' 'heal' 'journey' Infinitives swebban hǣlan sīðian tō swebbanne tō hǣlanne tō sīðianne Present Indicative ic swebbe hǣle sīðie þū swefest hǣlst sīðast hē/hit/hēo swefeþ hǣlþ sīðað wē/gē/hīe swebbaþ hǣlaþ sīðiað Past Indicative ic swefede hǣlde sīðode þū swefedest hǣldest sīðodest hē/hit/hēo swefede hǣle sīðode wē/gē/hīe swefedon hǣlon sīðodon Present Subjunctive ic/þū/hē/hit/hēo swebbe hǣle sīðie wē/gē/hīe swebben hǣlen sīðien Past Subjunctive ic/þū/hē/hit/hēo swefede hǣlde sīðode wē/gē/hīe swefeden hǣlden sīðoden Imperative Singular swefe hǣl sīða Plural swebbaþ hǣlaþ sīðiað Present Participle swefende hǣlende sīðiende Past Participle swefed hǣled sīðod During the Old English period the third class was significantly reduced; only four verbs belonged to this group: habban 'have', libban 'live', secgan 'say', and hycgan 'think'. Each of these verbs is distinctly irregular, though they share some commonalities.

Conjugation Pronoun 'have' 'live' 'say' 'think' Infinitive habban libban, lifgan secgan hycgan Present Indicative ic hæbbe libbe, lifge secge hycge þū hæfst, hafast lifast, leofast segst, sagast hygst, hogast hē/hit/hēo hæfð, hafað lifað, leofað segð, sagað hyg(e)d, hogað wē/gē/hīe habbaþ libbað secgaþ hycgað Past Indicative (all persons) hæfde lifde, leofode sægde hog(o)de, hygde Present Subjunctive (all persons) hæbbe libbe, lifge secge hycge Past Subjunctive (all persons) hæfde lifde, leofode sægde hog(o)de, hygde Imperative Singular hafa leofa sæge, saga hyge, hoga Plural habbaþ libbaþ, lifgaþ secgaþ hycgaþ Present Participle hæbbende libbende, lifgende secgende hycgende Past Participle gehæfd gelifd gesægd gehogod Preterite-present verbs

The preterite-present verbs are a class of verbs which have a present tense in the form of a strong preterite and a past tense like the past of a weak verb. These verbs derive from the subjunctive or optative use of preterite forms to refer to present or future time. For example, witan, "to know" comes from a verb which originally meant "to have seen" (cf. OE wise "manner, mode, appearance"; Latin videre "to see" from the same root). The present singular is formed from the original singular preterite stem and the present plural from the original plural preterite stem. As a result of this history, the first-person singular and third-person singular are the same in the present.

Few preterite present appear in the Old English corpus, and some are not attested in all forms.

Note that the Old English meanings of many of the verbs are significantly different than that of the modern descendants; in fact, the verbs "can, may, must" appear to have chain shifted in meaning.

Conjugation Pronoun 'know, know how to' 'be able to, can' 'be obliged to, must' 'know' 'own' 'avail' 'dare' 'remember' 'need' 'be allowed to, may' 'grant, allow, wish' 'have use of, enjoy' Modern Descendant 'can' 'may' 'shall' 'wit (obsolescent)' 'owe' 'dow (archaic)' 'dare' -- -- 'mote (archaic), must’ -- -- Infinitives cunnan magan sculan witan āgan dugan *durran munan þurfan *mōtan unnan *ge-/ *benugan Present Indicative ic cann mæg sceal wāt āh deah dearr man þearf mōt ann geneah þū canst meaht scealt wāst āhst dearst manst þearft mōst hē/hit/hēo cann mæg sceal wāt āh deah dearr man þearf mōt ann geneah wē/gē/hīe cunnon magon sculon witon āgon dugon durron munon þurfon mōton unnon genugan Past Indicative ic cūðe meahte sceolde wisse, wiste āhte dohte dorst munde þorfte mōste uðe benohte þū cūðest meahtest sceoldest wissest, wistest āhte dohte dorst munde þorfte mōste uðe benohte hē/hit/hēo cūðe meahte sceolde wisse, wiste āhte dohte dorst munde þorfte mōste ūðe benohte wē/gē/hīe cūðon meahton sceoldon wisson, wiston uþon Present Subjunctive ic/þū/hē/hit/hēo cunne mæge scyle, scule wite āge dyge, duge dyrre, durre myne, mune þyrfe, þurfe mōte unne wē/gē/hīe cunnen mægen sculen witaþ Past Subjunctive ic/þū/hē/hit/hēo cūðe meahte sceolde wisse, wiste wē/gē/hīe cūðen meahten sceolden [Forms above with asterisk (*) unattested.]

Anomalous verbs

Additionally there is a further group of four verbs which are anomalous, the verbs "want" (modern "will"), "do", "go" and "be". These four have their own conjugation schemes which differ significantly from all the other classes of verb. This is not especially unusual: "want", "do", "go", and "be" are the most commonly used verbs in the language, and are very important to the meaning of the sentences in which they are used. Idiosyncratic patterns of inflection are much more common with important items of vocabulary than with rarely-used ones.

Dōn 'to do' and gān 'to go' are conjugated alike; willan 'to want' is similar outside of the present tense.

Conjugation Pronoun 'do' 'go' 'will' Infinitive – dōn gān willan Present Indicative ic dō gā wille þū dēst gǣst wilt hē/hit/hēo dēð gǣð wile wē/gē/hīe dōð gāð willað Past Indicative ic/hē/hit/hēo dyde ēode wolde þū dydest ēodest woldest wē/gē/hīe dydon ēodon woldon Present Subjunctive (all persons) dō gā wille Past Subjunctive (all persons) dyde ēode wolde Present Participle dōnde – willende Past Participle gedōn gegān – The verb 'to be' is actually composed of three different stems:

Conjugation Pronoun sindon bēon wesan Infinitive – sindon bēon wesan Present Indicative ic eom bēo wese þū eart bist wesst hē/hit/hēo is bið wes(t) wē/gē/hīe sind(on) bēoð wesað Past Indicative ic – – wæs þū – – wǣre hē/hit/hēo – – wæs wē/gē/hīe – – wǣron Present Subjunctive ic/þū/hē/hit/hēo sīe bēo wese wē/gē/hīe sīen bēon wesen Past Subjunctive ic/þū/hē/hit/hēo – – wǣre wē/gē/hīe – – wǣren Imperative (singular) – bēo wes (plural) – bēoð wesað Present Participle – bēonde wesende Past Participle – gebēon – The present forms of wesan are almost never used. Therefore, wesan is used as the past, imperative, and present participle versions of sindon, and does not have a separate meaning. The bēon forms are usually used in reference to future actions. Only the present forms of bēon contrast with the present forms of sindon/wesan in that bēon tends to be used to refer to eternal or permanent truths, while sindon/wesan is used more commonly to refer to temporary or subjective facts. This semantic distinction was lost as Old English developed into modern English, so that the modern verb 'to be' is a single verb which takes its present indicative forms from sindon, its past indicative forms from wesan, its present subjunctive forms from bēon, its past subjunctive forms from wesan, and its imperative and participle forms from bēon.

Nouns

Old English is an inflected language, and as such its nouns, pronouns, adjectives and determiners must be declined in order to serve a grammatical function. A set of declined forms of the same word pattern is called a declension. As in several other ancient Germanic languages, there are five major cases: nominative, accusative, dative, genitive and instrumental.

- The nominative case indicated the subject of the sentence, for example se cyning means 'the king'. It was also used for direct address. Adjectives in the predicate (qualifying a noun on the other side of 'to be') were also in the nominative.

- The accusative case indicated the direct object of the sentence, for example Æþelbald lufode þone cyning means "Æþelbald loved the king", where Æþelbald is the subject and the king is the object. Already the accusative had begun to merge with the nominative; it was never distinguished in the plural, or in a neuter noun.

- The genitive case indicated possession, for example the þæs cyninges scip is "the ship of the king" or "the king's ship". It also indicated partitive nouns.

- The dative case indicated the indirect object of the sentence, for example hringas þæm cyninge means "rings for the king" or "rings to the king". There were also several verbs that took direct objects in the dative.

- The instrumental case indicated an instrument used to achieve something, for example, lifde sweorde, "he lived by the sword", where sweorde is the instrumental form of sweord. During the Old English period, the instrumental was falling out of use, having largely merged with the dative. Only pronouns and strong adjectives retained separate forms for the instrumental.

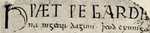

The small body of evidence we have for Runic texts suggests that there may also have a been a separate locative case in early or Northumbrian forms of the language (e.g., ᚩᚾ ᚱᚩᛞᛁ on rodi "on the Cross").[2]

In addition to inflection for case, nouns take different endings depending on whether the noun was in the singular (for example, hring 'one ring') or plural (for example, hringas 'many rings'). Also, some nouns pluralize by way of Umlaut, and some undergo no pluralizing change in certain cases.

Nouns are also categorised by grammatical gender – masculine, feminine, or neuter. In general, masculine and neuter words share their endings. Feminine words have their own subset of endings. The plural of some declension types distinguishes between genders, e.g., a-stem masculine nominative plural stanas "stones" vs. neuter nominative plural scipu "ships" and word "words"; or i-stem masculine nominative plural sige(as) "victories" vs. neuter nominative plural sifu "sieves" and hilt "hilts".

Furthermore, Old English nouns are divided as either strong or weak. Weak nouns have their own endings. In general, weak nouns are easier than strong nouns, since they had begun to lose their declensional system. However, there is a great deal of overlap between the various classes of noun: they are not totally distinct from one another.

Old English language grammars often follow the common NOM-ACC-GEN-DAT-INST order used for the Germanic languages.

Strong nouns

Here are the strong declensional endings and examples for each gender:

The Strong Noun Declension Case Masculine Neuter Feminine Singular Plural Singular Plural Singular Plural Nominative – -as – -u/– -u/– -a Accusative – -as – -u/– -e -a, -e Genitive -es -a -es -a -e -a Dative -e -um -e -um -e -um For the '-u/–' forms above, the '-u' is used with a root consisting of a single short syllable or ending in a long syllable followed by a short syllable, while roots ending in a long syllable or two short syllables are not inflected. (A long syllable contains a long vowel or is followed by two consonants. Note also that there are some exceptions; for example, feminine nouns ending in -þu such as strengþu 'strength'.)

Example of the Strong Noun Declension for each Gender Case Masculine

engel 'angel'Neuter

scip 'ship'Feminine

sorg 'sorrow'Singular Plural Singular Plural Singular Plural Nominative engel englas scip scipu sorg sorga Accusative engel englas scip scipu sorge sorga/sorge Genitive engles engla scipes scipa sorge sorga Dative engle englum scipe scipum sorge sorgum Note the syncope of the second e in engel when an ending follows. This syncope of the vowel in the second syllable occurs with two-syllable strong nouns, which have a long vowel in the first syllable and a second syllable consisting of a short vowel and single consonant (for example, engel, wuldor 'glory', and hēafod 'head'). However, this syncope is not always present, so forms such as engelas may be seen.

Weak nouns

Here are the weak declensional endings and examples for each gender:

The Weak Noun Declension Case Masculine Neuter Feminine Singular Plural Singular Plural Singular Plural Nominative -a -an -e -an -e -an Accusative -an -an -e -an -an -an Genitive -an -ena -an -ena -an -ena Dative -an -um -an -um -an -um Example of the Weak Noun Declension for each Gender Case Masculine

nama 'name'Neuter

ēage 'eye'Feminine

tunge 'tongue'Singular Plural Singular Plural Singular Plural Nominative nama naman ēage ēagan tunge tungan Accusative naman naman ēage ēagan tungan tungan Genitive naman namena ēagan ēagena tungan tungena Dative naman namum ēagan ēagum tungan tungum Irregular strong nouns

In addition, masculine and neuter nouns whose main vowel is short 'æ' and end with a single consonant change the vowel to 'a' in the plural (a result of the phonological phenomenon known as Anglo-Frisian brightening):

Dæg 'day' m. Case Singular Plural Nominative dæg dagas Accusative dæg dagas Genitive dæges daga Dative dæge dagum Some masculine and neuter nouns end in -e in their base form. These drop the -e and add normal endings. Note that neuter nouns in -e always have -u in the plural, even with a long vowel:

Example of the Strong Noun Declensions ending in -e Case Masculine

ende 'end'Neuter

stȳle 'steel'Singular Plural Singular Plural Nominative ende endas stȳle stȳlu Accusative ende endas stȳle stȳlu Genitive endes enda stȳles stȳla Dative ende endum stȳle stȳlum Nouns ending in -h lose this when an ending is added, and lengthen the vowel in compensation (this can result in compression of the ending as well):

Example of the Strong Noun Declensions ending in -h Case Masculine

mearh 'horse'Neuter

feorh 'life'Masculine

scōh 'shoe'Singular Plural Singular Plural Singular Plural Nominative mearh mēaras feorh feorh scōh scōs Accusative mearh mēaras feorh feorh scōh scōs Genitive mēares mēara fēores fēora scōs scōna Dative mēare mēarum fēore fēorum scō scōm Nouns whose stem ends in -w change this to -u or drop it in the nominative singular. (Note that this '-u/–' distinction depends on syllable weight, as for strong nouns, above.)

Example of the Strong Noun Declensions ending in -w Case Neuter

smeoru 'grease'Feminine

sinu 'sinew'Feminine

lǣs 'pasture'Singular Plural Singular Plural Singular Plural Nominative smeoru smeoru sinu sinwa lǣs lǣswa Accusative smeoru smeoru sinwe sinwa, -e lǣswe lǣswa, -e Genitive smeorwes smeorwa sinwe sinwa lǣswe lǣswa Dative smeorwe smeorwum sinwe sinwum lǣswe lǣswum A few nouns follow the -u declension, with an entirely different set of endings. The following examples are both masculine, although feminines also exist, with the same endings (for example duru 'door' and hand 'hand'). Note that the '-u/–' distinction in the singular depends on syllable weight, as for strong nouns, above.

Example of the -u Declension Case Masculine

sunu 'son'Masculine

feld 'field'Singular Plural Singular Plural Nominative sunu suna feld felda Accusative sunu suna feld felda Genitive suna suna felda felda Dative suna sunum felda feldum Mutating strong nouns

There are also some nouns of the consonant declension, which show i-umlaut in some forms.

Example of the Strong Noun Declensions with i-shift Case Masculine

fōt 'foot'Feminine

hnutu 'nut'Feminine

bōc 'book'Singular Plural Singular Plural Singular Plural Nominative fōt fēt hnutu hnyte bōc bēc Accusative fōt fēt hnutu hnyte bōc bēc Genitive fōtes fōta hnyte, hnute hnuta bēc, bōce bōca Dative fēt, fōte fōtum hnyte, hnute hnutum bēc, bōc bōcum Other such nouns include (with singular and plural nominative forms given):

Masculine: tōþ, tēþ 'tooth'; mann, menn 'man'; frēond, frīend 'friend'; fēond, fīend 'enemy' (cf. 'fiend')

Feminine: studu, styde 'post' (cf. 'stud'); hnitu, hnite 'nit'; āc, ǣc 'oak'; gāt, gǣt 'goat'; brōc, brēc 'leg covering' (cf. 'breeches'); gōs, gēs 'goose'; burg, byrg 'city' (cf. 'borough', '-bury' and German cities in -burg); dung, dyng 'prison' (cf. 'dungeon' by way of French and Frankish); turf, tyrf 'turf'; grūt, grȳt 'meal' (cf. 'grout'); lūs, lȳs 'louse'; mūs, mȳs 'mouse'; neaht, niht 'night' Feminine with loss of -h in some forms: furh, fyrh 'furrow' or 'fir'; sulh, sylh 'plough'; þrūh, þrȳh 'trough'; wlōh, wlēh 'fringe'. Feminine with compression of endings: cū, cȳ 'cow' (cf. dialectal plural 'kine')

Neuter: In addition, scrūd 'clothing, garment' has the umlauted dative-singular form scrȳd.

Nouns of relationship

Nouns of Relationship Case Masculine

fæder 'father'Masculine

brōðor 'brother'Feminine

mōdor 'mother'Feminine

sweostor 'sister'Feminine

dohtor 'daughter'Singular Plural Singular Plural Singular Plural Singular Plural Singular Plural Nominative fæder fæd(e)ras brōðor (ge)brōðor mōdor mōdra/mōdru sweostor (ge)sweostor, -tru, -tra dohtor dohtor Accusative fæder fæd(e)ras brōðor (ge)brōðor mōdor mōdra/mōdru sweostor (ge)sweostor, -tru, -tra dohtor dohtor Genitive fæder fæd(e)ra brōðor (ge)brōðra mōdor mōdra sweostor (ge)sweostra dohtor dohtra Dative fæder fæderum brēðer (ge)brōðrum mēder mōdrum sweostor (ge)sweostrum dehter dohtrum Neuter nouns with -r- in the plural

Lamb 'lamb' n. Case Singular Plural Nominative lamb lambru Accusative lamb lambru Genitive lambes lambra Dative lambe lambrum Other such nouns: ǣg, ǣgru 'egg' (ancestor of the archaic/dialectical form 'ey', plural 'eyren'; the form 'egg' is a borrowing from Old Norse); bread, breadru 'crumb'; cealf, cealfru 'calf'; cild 'child' has either the normal plural cild or cildru (cf. 'children', with -en from the weak nouns); hǣmed, hǣmedru 'cohabitation'; speld, speldru 'torch'.

Adjectives

Adjectives in Old English are declined using the same categories as nouns: five cases (nominative, accusative, genitive, dative, and instrumental), three genders (masculine, feminine, neuter), and two numbers (singular, plural). In addition, they can be declined either strong or weak. The weak forms are used in the presence of a definite or possessive determiner, while the strong ones are used in other situations. The weak forms are identical to those for nouns, while the strong forms use a combination of noun and pronoun endings:

The Strong Adjective Declension Case Masculine Neuter Feminine Singular Plural Singular Plural Singular Plural Nominative – -e – -u/– -u/– -e, -a Accusative -ne -e – -u/– -e -e, -a Genitive -es -ra -es -ra -re -ra Dative -um -um -um -um -re -um Instrumental -e -um -e -um -re -um For the '-u/–' forms above, the distinction is the same as for strong nouns.

Example of the Strong Adjective Declension: gōd 'good' Case Masculine Neuter Feminine Singular Plural Singular Plural Singular Plural Nominative gōd gōde gōd gōd gōd gōde, -a Accusative gōdne gōde gōd gōd gōde gōde, -a Genitive gōdes gōdra gōdes gōdra gōdre gōdra Dative gōdum gōdum gōdum gōdum gōdre gōdum Instrumental gōde gōdum gōde gōdum gōdre gōdum Example of the Weak Adjective Declension: gōd 'good' Case Masculine Neuter Feminine Singular Plural Singular Plural Singular Plural Nominative gōda gōdan gōde gōdan gōde gōdan Accusative gōdan gōdan gōde gōdan gōdan gōdan Genitive gōdan gōdena gōdan gōdena gōdan gōdena Dative gōdan gōdum gōdan gōdum gōdan gōdum Instrumental gōdan gōdum gōdan gōdum gōdan gōdum Note that the same variants described above for nouns also exist for adjectives. The following example shows both the æ/a variation and the -u forms in the feminine singular and neuter plural:

Example of the Strong Adjective Declension: glæd 'glad' Case Masculine Neuter Feminine Singular Plural Singular Plural Singular Plural Nominative glæd glade glæd gladu gladu glade Accusative glædne glade glæd gladu glade glade Genitive glades glædra glades glædra glædre glædra Dative gladum gladum gladum gladum glædre gladum Instrumental glade gladum glade gladum glædre gladum The following shows an example of an adjective ending with -h:

Example of the Strong Adjective Declension: hēah 'high' Case Masculine Neuter Feminine Singular Plural Singular Plural Singular Plural Nominative hēah hēa hēah hēa hēa hēa Accusative hēane hēa hēah hēa hēa hēa Genitive hēas hēara hēas hēara hēare hēara Dative hēam hēam hēam hēam hēare hēam Instrumental hēa hēam hēa hēam hēare hēam The following shows an example of an adjective ending with -w:

Example of the Strong Adjective Declension: gearu 'ready' Case Masculine Neuter Feminine Singular Plural Singular Plural Singular Plural Nominative gearu gearwe gearu gearu gearu gearwe Accusative gearone gearwe gearu gearu gearwe gearwe Genitive gearwes gearora gearwes gearora gearore gearora Dative gearwum gearwum gearwum gearwum gearore gearwum Instrumental gearwe gearwum gearwe gearwum gearore gearwum Determiners

Old English had two main determiners: se, which could function as both 'the' or 'that', and þes for 'this'.

the/that Case Masculine Neuter Feminine Plural Nominative se þæt sēo þā Accusative þone þæt þā þā Genitive þæs þæs þǣre þāra, þǣra Dative þǣm þǣm þǣre þǣm, þām Instrumental þȳ, þon þȳ, þon – – Modern English 'that' descends from the neuter nominative/accusative form,[3] and 'the' from the masculine nominative form, with 's' replaced analogously by the 'th' of the other forms.[4] The feminine nominative form was probably the source of Modern English 'she.'[5]

this Case Masculine Neuter Feminine Plural Nominative þes þis þēos þās Accusative þisne þis þās þās Genitive þisses þisses þisse, þisre þisra Dative þissum þissum þisse, þisre þissum Instrumental þȳs þȳs – – Pronouns

Most pronouns are declined by number, case and gender; in the plural form most pronouns have only one form for all genders. Additionally, Old English pronouns reserve the dual form (which is specifically for talking about groups of two things, for example "we two" or "you two" or "they two"). These were uncommon even then, but remained in use throughout the period.

First Person Case Singular Plural Dual Nominative ic, īc wē wit Accusative mec, mē ūsic, ūs uncit, unc Genitive mīn ūre uncer Dative mē ūs unc Second Person Case Singular Plural Dual Nominative þū gē git Accusative þēc, þē ēowic, ēow incit, inc Genitive þīn ēower incer Dative þē ēow inc Third Person Case Singular Plural Masc. Neut. Fem. Nominative hē hit hēo hiē m., hēo f. Accusative hine hit hīe hiē m., hīo f. Genitive his his hire hiera m., heora f. Dative him him hire him Many of the forms above bear strong resemblances to their contemporary English language equivalents: for instance in the genitive case ēower became "your", ūre became "our", mīn became "mine".

Prepositions

Prepositions (like Modern English words by, for, and with) often follow the word which they govern, in which case they are called postpositions. Also, so that the object of a preposition was marked in the dative case, a preposition may conceivably be located anywhere in the sentence, even appended to the verb. e.g. "Scyld Scefing sceathena threatum meodo setla of teoh" means "Scyld took mead settles of (from) enemy threats." The infinitive is not declined.

The following is a list of prepositions in the Old English language. Many of them, particularly those marked "etc.", are found in other variant spellings. Prepositions may govern the accusative, genitive, dative or instrumental cases - the question of which is beyond the scope of this article.

Prepositions Old English Definition Notes æfter after; along, through, during; according to, by means of; about. Ancestor of modern after Related to Dutch achter = behind, after ǣr before Related to modern German eher and Dutch eer, ancestor of modern ere æt at, to, before, next, with, in, for, against; unto, as far as. Ancestor of modern at and against, before, on. andlang along Ancestor of modern along bæftan after, behind; without. be, bī by, near to, to, at, in, on, upon, about, with; of, from, about, touching, concerning; for, because of, after, by, through, according to; beside, out of. Related to modern German bei, ancestor of modern by befōran before. Ancestor of modern before begeondan beyond. Ancestor of modern beyond behindan behind. Ancestor of modern behind beinnan in, within. beneoðan beneath. Ancestor of modern beneath betweonum, betweox, etc. betwixt, between, among, amid, in the midst. Ancestors of modern between and betwixt respectively bīrihte near. būfan above. Ancestor of modern above through compound form onbúfan būtan out of, against; without, except. eāc with, in addition to, besides. Related to modern German auch for for, on account of, because of, with, by; according to; instead of. Ancestor of modern for fōr, fōre before. fram from; concerning, about, of. Ancestor of modern from gemang among Ancestor of modern among geond through, throughout, over, as far as, among, in, after, beyond. Ancestor of modern yonder through comparative form geondra in in, on; into, to. Ancestor of modern in innan in, into, within, from within. intō into Ancestor of modern into mid with, against Ancestor of modern amid through related form onmiddan neāh near Ancestor of modern nigh nefne except of of, from, out of, off. Ancestor of modern of and off ofer above, over; upon, on; throughout; beyond, more than Ancestor of modern over on on; in, at; Ancestor of modern on onbūtan about Ancestor of modern about ongeagn, etc. opposite, against; towards; in reply to. Ancestor of modern again onuppan upon, on. oþ to, unto, up to, as far as. samod with, at. tō to, at. Ancestor of modern to tōeācan in addition to, besides. tōforan before. tōgeagnes towards, against. tōmiddes in the midst of, amidst. tōweard toward. Ancestor of modern toward þurh through Related to modern German durch, ancestor of modern through ufenan above, besides. under under. Ancestor of modern under underneoþan underneath. Ancestor of modern underneath uppan upon, on. Not the ancestor of modern upon, which came from "up on". ūtan without, outside of Related to modern German außen, außer and Swedish utan wið towards, to; with, against; opposite to; by, near. Ancestor of modern with wiðæftan behind. wiðer against. Related to modern German wider wiðinnan within. Ancestor of modern within wiðforan before. wiðoutan without, outside of. Ancestor of modern without ymb about, by. Related to German um and Latin ambi ymbūtan about, around; concerning. Syntax

Old English syntax was similar in many ways to that of modern English. However, there were some important differences. Some were simply consequences of the greater level of nominal and verbal inflection – e.g., word order was generally freer. But there are also differences in the default word order, and in the construction of negation, questions, relative clauses and subordinate clauses.

In addition:

- The default word order was verb-second and more like modern German than modern English.

- There was no do-support in questions and negatives.

- Multiple negatives could stack up in a sentence, and intensified each other (negative concord).

- Sentences with subordinate clauses of the type "When X, Y" did not use a wh-type word for the conjunction, but instead used interrogative pronouns asa word related to "when", but instead a th-type correlative conjunction (e.g. þā X, þā Y in place of "When X, Y").

Word order

There was some flexibility in word order of Old English, since the heavily inflected nature of nouns, adjectives and verbs often indicated the relationships among clause arguments. Scrambling of constituents was common, and even sometimes scrambling within a constituent occurred, as in Beowulf line 708 wrāþum on andan:

wrāþum on andan hostile.DAT.SG on/with malice.DAT.SG "with hostile malice" Something similar occurs in line 713 in sele þām hēan "in the high hall" (lit. "in hall the high").

Extraposition of constituents out of larger constituents is common even in prose, as in the well-known tale of Cynewulf and Cyneheard, which begins

- Hēr Cynewulf benam Sigebryht his rīces ond Westseaxna wiotan for unryhtum dǣdum, būton Hamtūnscīre; ...

- (word-for-word) "Here Cynewulf deprived Sigebryht of his kingdom and West Saxons' counselors for unright deeds, except Hampshire"

- (translated) "Here Cynewulf and the West Saxon counselors deprived Sigebryht of his kingdom, other than Hampshire, for unjust actions"

Note how the words ond Westseaxna wiotan "and the West Saxon counselors" (lit. "and (the) counselors of (the) West Saxons") have been extraposed from (moved out of) the compound subject they belong in, in a way that would be totally impossible in modern English. Case marking helps somewhat: wiotan "counselors" can be nominative or accusative but definitely not genitive, which is the case of rīces "kingdom" and the case governed by benam "deprived"; hence, Cynewulf can't possibly have deprived Sigebryht of the West Saxon counselors, as the order suggests.

Main clauses in Old English tend to have a verb-second (V2) order, where the verb is the second constituent in a sentence, regardless of what comes first. There are echoes of this in modern English, e.g. "Hardly did he arrive when ...", "Never can it be said that ...", "Over went the boat", "Ever onward marched the weary soldiers ...", "Then came a loud sound from the sky above". In Old English, however, it was much more extensive, much as in modern German. Note that if the subject appears first, this yields an SVO order; but it can also yield orders such as OVS, CVSO, etc.

In subordinate clauses, however, the word order is completely different, with verb-final constructions the norm – again as in modern German. Furthermore, in poetry, all these rules were frequently broken. In Beowulf, for example, main clauses frequently have verb-initial or verb-final order, and subordinate clauses often have verb-second order. (However, in clauses introduced by þā, which can mean either "when" or "then" and where word order is crucial for telling the difference, the normal word order is nearly always followed.)

Those linguists who work within the Chomskyan transformational grammar paradigm often believe that it is more accurate to describe Old English (and other Germanic languages with the same word-order patterns, e.g. modern German) as having underlying subject-object-verb (SOV) ordering. According to this theory, all sentences are initially generated using this order, but then in main clauses the verb is moved back to the V2 position (technically, the verb undergoes V-to-T raising). This is said to explain the fact that Old English allows inversion of subject and verb as a general strategy for forming questions, while modern English only uses this strategy with auxiliary verbs and main-verb "to be" (and occasionally main-verb "to have", especially in British English), requiring do-support in other cases.

Questions

Because of its similarity with Old Norse, it is believed that most of the time the word order of Old English changed when asking a question, from SVO to VSO; i.e. swapping the verb and the subject. While many purport that Old English had free word order, this is not quite true and there were conventions for the positioning of subject, object and verb in the clause.

- "I am..." becomes "Am I..."

- "Ic eom..." becomes "Eom ic..."

Relative, subordinate clauses

Old English did not use forms equivalent to "who, when, where" in relative clauses (as in "The man who I saw") or subordinate clauses ("When I got home, I went to sleep").

Instead, relative clauses used one of the following:

- An invariable complementizer þe

- The demonstrative pronoun se, sēo, þat

- The combination of the two, as in se þe

Preposition-fronting ("The man with whom I spoke") did not normally occur.

Subordinate clauses tended to use correlative conjunctions, e.g.

- Þā ic hām ēode, þā slēp ic.

- (word-for-word) "Then I home went, then slept I."

- (translated) "When I went home, I slept."

The word order usually distinguished the subordinate clause (with verb-final order) from the main clause (with verb-second word order).

The equivalents of "who, when, where" were used only as interrogative pronouns and indefinite pronouns, as in Ancient Greek and Sanskrit.

Besides þā ... þā ..., other correlative conjunctions occurred, often in pairs of identical words, e.g.:

- þǣr X, þǣr Y: "Where X, Y"

- þanon X, þanon Y: "Whence (from where) X, Y"

- þider X, þider Y: "Whither (to where) X, Y"

- þēah (þe) X, þēah Y: "Although X, Y"

- þenden X, þenden Y: "While X, Y"

- þonne X, þonne Y: "Whenever X, Y"

- þæs X, þæs Y: "As/after/since X, Y"

- þȳ X, þȳ Y: "The more X, the more Y"

Phonology

Main article: Old English phonologyThe phonology of Old English is necessarily somewhat speculative, since it is preserved purely as a written language. Nevertheless, there is a very large corpus of Old English, and the written language apparently indicates phonological alternations quite faithfully, so it is not difficult to draw certain conclusions about the nature of Old English phonology.

See also

Notes

- ^ Peter S. Baker (2003). "Pronouns". The Electronic Introduction to Old English. Oxford: Blackwell. http://www.wmich.edu/medieval/resources/IOE/inflpron.html.

- ^ Page, An Introduction to English Runes, Boydell 1999, p. 230

- ^ "That". Online Etymology Dictionary. http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=that. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ "The". Online Etymology Dictionary. http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=the. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ "She". Online Etymology Dictionary. http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=she. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

References

- Moore, Samuel, and Thomas A. Knott. The Elements of Old English. 1919. Ed. James R. Hulbert. 10th ed. Ann Arbor, Michigan: George Wahr Publishing Co., 1958.

- The Magic Sheet, one page color PDF summarizing Old English declension, from Peter S. Baker, inspired by Moore and Marckwardt's 1951 Historical Outlines of English Sounds and Inflections

- J. Bosworth & T.N. Toller, An Anglo-Saxon dictionary: Germanic Lexicon Project

Further reading

- Brunner, Karl (1965). Altenglische Grammatik (nach der angelsächsischen Grammatik von Eduard Sievers neubearbeitet) (3rd ed.). Tübingen: Max Niemeyer.

- Campbell, A. (1959). Old English Grammar. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Mitchell, Bruce & Robinson, Fred (2001) A Guide to Old English; 6th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing ISBN 0-631-22636-2

- Quirk, Randolph; & Wrenn, C. L. (1957). An Old English Grammar (2nd ed.) London: Methuen.

Categories:- Old English grammar

- Grammars of specific languages

- Old English language

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.