- Danube Valley Railway (Baden-Württemberg)

-

This article is about the railway line by this name in Baden-Württemberg. For the line running from Regensburg to Ulm in Bavaria, see Danube Valley Railway (Bavaria).

Danube Valley Railway

(Donautalbahn)

Ulm–DonaueschingenRoute number: See text Line number: 4540 Ulm–Sigmaringen

4630 Sigmaringen–Inzigkofen

4660 Inzigkofen–Tuttlingen

4630 Tuttlingen–Immendingen

4250 Immendingen–DonaueschingenLine length: 164 km (101.9 mi) Gauge: 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) Maximum incline: ? % Route Information Country: Germany Land: Baden-Württemberg Type of route: Main Line Legend

from Neu-Ulm:

Danube Valley Railway (Bavaria) from Regensburg,

Ulm–Augsburg railway from Munich,

Iller Valley Railway from Oberstdorf

Bridge over the Danube

Southern Railway from Friedrichshafen

0,0 Ulm Hbf 478 m

Brenz Railway to Aalen,

Fils Valley Railway to Stuttgart

0,8 B10 overbridge

1,7 Ulm Rbf 482 m

2,0 overbridge near Blaubeurer Tor in Ulm (30 m)

2,4 Ulm-Söflingen 484 m

3,1 Bridge over the Blau

5,7 Blaustein 492 m

6,7 Klingenstein

7,0 Bridge over the Blau

7,5 Herrlingen 497 m

13,0 Bridge over the B28

15,3 Gerhausen 516 m

15,9 Bridge over the Blau

16,5 Blaubeuren 518 m

22,7 Schelklingen 535 m

Swabian Alb Railway to Kleinengstingen

24,2 Schmiechen 543 m

28,3 Allmendingen 519 m

32,1 Berkach

32,7 B311 overbridge

33,6 Ehingen (Donau) 510 m

36,9 Dettingen (b Ehingen)

40,7 Rottenacker 501 m

45,0 Munderkingen 506 m

47,8 Untermarchtal

48,3 B311 overbridge

52,6 Rechtenstein 516 m

Feldbahn to Rechtenstein hydro-electric power station

52,7 Bridge over the Danube at Rechtenstein

57,3 Bridge over the Danube at Zwiefaltendorf

57,7 Zwiefaltendorf 524 m

58,4 Bridge over the Danube

61,7 Unlingen

Federsee Railway from Bad Schussenried

64,5 Bridge over the B312

65,2 Riedlingen 530 m

67,7 Neufra (Donau)

71,0 Ertingen 539 m

Zollernalb Railway from Aulendorf

76,4 Herbertingen 548 m

81,8 Bridge over the B311

82,4 Mengen 560 m

Hegau-Ablachtal Railway to Radolfzell

83,9 Ennetach

86,0 Scheer

86,2 Schlossberg Tunnel in Scheer (95 m)

92,2 Bridge over the Danube at Scheer

89,1 Sigmaringendorf 575 m

Bridge over the Danube at Sigmaringen

Zollernalb Railway 2 from Hechingen

Sigmaringen–Krauchenwies railway

92,6 41,2 Sigmaringen 572 m

Bridge over the Danube at Sigmaringen

37,1 Inzigkofen 580 m

Zollernalb Railway to Tübingen

34,3 Bridge over the Schmeie

34,3 Bridge over the Danube near Dietfurth

34,2 Dietfurth Tunnel near Gutenstein (74 m)

33,0 Gutenstein 587 m

32,3 Bridge over the Danube at Gutenstein

31,6 Bridge over the Danube

31,1 Thiergarten Tunnel near Thiergarten (275 m)

30,9 Bridge over the Danube near Thiergarten

30,5 Thiergarten (Hohenz) 595 m

23,6 Hausen im Tal 599 m

19,3 Käpfle Tunnel near Beuron (181 m)

19,1 Bridge over the Danube

17,4 Beuron 618 m

16,5 Bridge over the Danube

14,4 Schanz Tunnel near Fridingen (684 m)

14,4 Bridge over the Bära

Junction to the Fridingen hammer works

13,7 Fridingen an der Donau 632 m

13,2 Bridge over the Danube

12,1 Bridge over the Danube

9,0 Mühlheim an der Donau 638 m

7,9 Stetten an der Donau

5,7 Nendingen 642 m

2,0 Tuttlingen Nord 646 m

0,9 Tuttlingen Zentrum

0,2 Bridge over the Danube at Tuttlingen

Gäu Railway from Stuttgart

0,0 151,0 Tuttlingen station 649 m

Gäu Railway to Singen

Tuttlingen Gänsäcker

153,7 Bridge over the Danube

154,3 Möhringen station 652 m

Möhringen Rathaus

Immendingen Mitte

Black Forest Railway from Singen/Konstanz

161,0 119,0 Immendingen 658 m

Immendingen-Zimmern

115,8 Hintschingen

Wutach Valley Railway to Waldshut

113,0 Geisingen

Bridge over the Danube near Geisingen

110,2 Gutmadingen

106,3 Neudingen

103,5 Pfohren

Hölle Valley Railway from Freiburg

and to the Breg Valley Railway to Bräunlingen

99,7 Donaueschingen 677 m

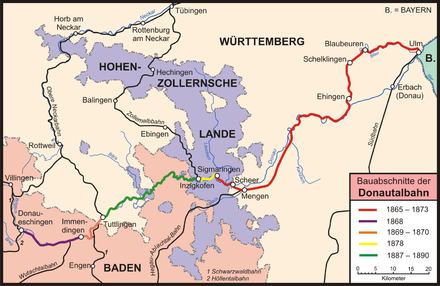

Black Forest Railway to Offenburg The Danube Valley Railway (German: Donautalbahn or Donaubahn) in Baden-Württemberg in south-western Germany is a 164-kilometer-long railway running from the city of Ulm to Donaueschingen, which is largely single-tracked and for the most part not electrified. The line is famous especially for its charming course through the Upper Danube Nature Park (Naturpark Obere Donau), and is particularly attractive to bicycle tourists. The Royal Württemberg State Railways and the Grand Duchy of Baden State Railways built the line as part of the railway projects undertaken between 1865 and 1890. The construction of the section between Tuttlingen and Inzigkofen was pushed through by the German general staff, for whom the Danube Valley Railway was seen as a strategic railway in case of another war with France. Since 1901, the Danube Valley Railway, together with the Höllentalbahn (Schwarzwald), form part of the pan-regional railway link from Ulm to Freiburg im Breisgau.

Route details

The Danube Valley Railway in the Upper Danube Nature Park seen from Knopfmacherfelsen

The Danube Valley Railway in the Upper Danube Nature Park seen from Knopfmacherfelsen

The Donautalbahn runs alongside the Danube river and crosses it several times. From the river's origin near Donaueschingen to Immendingen, the line shares tracks with the Schwarzwaldbahn (Baden), then runs across the Upper Danube Nature Park (Naturpark Obere Donau), brushing up against the southern edge of the Schwäbische Alb, all the while following the course of the Danube. Between the towns of Inzigkofen and Herbertingen, the Donautalbahn again shares its tracks, this time with the Zollernalbbahn. At Ehingen (Donau), the line leaves what is known as the Danube valley today, and follows the valley formed by the Danube in times past, along the rivers Schmiech, Ach, and Blau. The railway again touches the border of the Schwäbische Alb between Allmendingen and Blaustein, and meets its eponymous river again at the line's terminus in Ulm.

The Donauradweg (Danube Bicycle Trail), which also goes from Donaueschingen to Ulm, and continues on to Vienna, runs parallel to the line for much of the way. The Donautalbahn has a reputation as one of the most beautiful railways in Germany, and its charming course through the Naturpark Obere Donau, and the boom in bicycle tourism on the Donauradweg, have made the line especially popular with bicyclists and hikers. The Donautalbahn is 164 kilometers in length, and traverses 5 districts of the state of Baden-Württemberg, as well as Ulm, which is not a constituent of a district, and is managed by a total of four public transport associations (Verkehrsbund). In Ulm, as well as in the districts of Alb-Donau and Biberach, namely between the stations Ulm Hauptbahnhof and Riedlingen, the Donautalbahn is part of the Donau-Iller-Nahverkehrsverbund (DING) transport association. In the district of Sigmaringen, between Herbertingen and Beuron, the railway is part of the public transport association Verkehrsverbund Neckar-Alb-Donau (naldo). Between Fridingen an der Donau and Geisingen, the line traverses the district of Tuttlingen, and its transport association TUTicket. The station in Donaueschingen is the one and only part of the Donautalbahn in the district of Schwarzwald-Baar, and its transport association Verkehrsverbund Schwarzwald-Baar (VSB).

The Donautalbahn is classified as a main line, even though it largely features just a single track, and is for the most part not electrified. Only the section between Ulm and Herrlingen, and the section between Immendingen and Donaueschingen, which is shared with the Schwarzwaldbahn (Baden), feature twin tracks. In the section between Ulm and Sigmaringen, the railway is certified to be used by trains with tilting technology.

Pan-regional significance

Together with the Höllentalbahn, which runs from Donaueschingen to Freiburg im Breisgau, the Donautalbahn forms what is easily the shortest railway connection between the major cities of Ulm and Freiburg, both located in Baden-Württemberg. The line was therefore significant outside of the immediate region, especially in terms on connections between Augsburg and Munich to Freiburg, and from Ulm via Tuttlingen into Switzerland. However, the importance of this pan-regional East-West connection has been markedly reduced in recent times, primarily due to the relatively low average speed on the line. This low speed is caused by the limitations imposed by the single track, which means often lengthy halts at node stations, and required stops at crossing points. In addition, the route along the Schmiech and Blau rivers also adds to the length of the trip. Today, connections via Stuttgart and Karlsruhe are significantly quicker for the trip from Munich or Ulm to Freiburg. In addition, in 2003 the Deutsche Bahn discontinued the Kleber-Express, which had used large portions of the Donautalbahn since 1954 to make a daily direct trip between Munich and Freiburg. This meant the end of the use of the line in providing direct connections between major cities in the area.

History

Border politics and first railway construction initiatives

The Donautalbahn was never conceived as one comprehensive railway from Ulm to Donaueschingen, and certainly not all the way to Freiburg im Breisgau, but came together as individual pieces of several railway projects, which were constructed over the course of about 25 years. Especially the borders between the states of Baden, Württemberg, and the Province of Hohenzollern, which became part of Prussia in 1850, made such comprehensive railway planning difficult. In just the section between Mengen in Württemberg and Immendingen in Baden, the Donautalbahn crosses state borders a total of ten times. The section between Ulm and Immendingen was built by the Royal Württemberg State Railways (Königlich Württembergischen Staats-Eisenbahnen or K.W.St.E.), while the section between Immendingen and Donaueschingen was constructed by the Baden State Railways (Badische Staatseisenbahnen). Prussia did not take part in the construction of the line, even though parts of it do run across the areas belonging to the Province of Hohenzollern.

Initial considerations of a rail line from Ulm along the Danube can be dated back to the 1850s. As was the case in other areas, cities and towns along the Danube started railway committees, which worked on finding support for the construction of a railway. In 1861, 17 of these committees published a memorandum, which argued for the construction of a line from Ulm via Ehingen, Mengen, Messkirch, and Singen to Schaffhausen in Switzerland, with a connection to Tuttlingen as well as to the Schwarzwaldbahn (Baden), which was still in its planning phase at the time. In addition, the construction of a railway along the Danube as part of a trans-European line between Vienna and Paris was under discussion. A connection between Ulm and Vienna already existed in the 1860s, and since Paris was already connected to Chaumont, Haute-Marne, closing the gap via construction of a railway from Ulm along the Danube to Donaueschingen, then further through the Schwarzwald to Freiburg, and across the Rhine river and the Vosges mountain range to Chaumont, found proponents amongst the committees along the Danube, and other parties, as the shortest route between Paris and Vienna. However, not only were there major topographical issues, which were difficult to solve given the knowledge of the day, but the many border crossings necessary to build this railway also added to the list of problems with the concept.

1865–1873: Construction of the section Ulm–Sigmaringen and Tuttlingen–Donaueschingen

Württemberg started with plans on a smaller scale, and, after negotiations with Baden and Prussia, received the right to build a railway to Sigmaringen in Hohenzollern, as well as to connect to the rail network of the state of Baden via the Hegau-Ablachtal-Bahn in Mengen, which meant a connection to the western edge of the Bodensee. On the 28th of April 1865, the legislative body (Landtag) of the state of Württemberg passed into law a bill to construct a railway from Ulm along the rivers Blau, Ach, and Schmiech to Ehingen, and further along the Danube to Sigmaringen. An alternative route, which would have been much shorter and less expensive, and which would have branched off the already extant Südbahn at Erbach and followed the course of the Danube, was dropped in favor of a railway that would connect the towns of Blaubeuren und Schelklingen to the rail network. Crucial to this decision was the influence wielded by the member of the legislature from Blaubeuren, Ferdinand von Steinbeis, who was given an honorary citizenship of the town of Blaubeuren for his support.[1] Construction started in 1865, and on the 13th of June 1868, the section between Ulm and Blaubeuren was opened for service.

In 1869 Ehingen was connected to the line, and the railway reached the town of Scheer on the border between Württemberg and Hohenzollern in 1870, with Charles I of Württemberg using the occasion to travel the line on a special train to Mengen. For the construction of the numerous tunnels and bridges across the Danube, the Royal Württemberg State Railways in particular hired workers from Italy. The advent of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870/71, as well as issues with the construction of some of the bridges, delayed the completion of the section from Scheer to Sigmaringen until 1873.

When the Royal Württemberg State Railways put into service the first section of the Donautalbahn between Ulm and Blaubeuren in 1868, construction by the Baden State Railways on the Schwarzwaldbahn in Baden from Singen to Offenburg had reached an advanced stage. On the 15th of June 1868, two days after the opening of the Donautalbahn section, the Schwarzwaldbahn-section between Engen and Donaueschingen was also opened for service, which, between Immendingen and Donaueschingen, follows the course of the Danube. Württemberg, which was following the progress of the Schwarzwaldbahn construction with great interest, now formulated the goal to connect their rail network to the new line in Baden. However, building an extension to the Donautalbahn from Sigmaringen to the connection point in Immendingen in Baden, which would have meant the early completion of the line, was not in the plans. Instead, Württemberg wanted to extend the Obere Neckarbahn, which parted ways from the Filstalbahn near Plochingen, and then reached Reutlingen, Tübingen, and, in 1867, Rottenburg am Neckar, with the extension going through Horb and Rottweil, and further through the Neckar valley in a south-westerly direction to the border between the two states, to establish a connection to the Schwarzwaldbahn (Baden) there. In addition to a route between Rottweil and Villingen, another railway was built from Rottweil to Tuttlingen, which was completed on the 15th of July 1869. Württemberg then further constructed the connecting line from Tuttlingen to Immendingen through the Danube valley, which was completed on the 26th of July 1870. This meant that the Donautalbahn-section between Tuttlingen and Immendingen was complete as a connecting line to the Schwarzwaldbahn (Baden), and the section between Immendingen and Donaueschingen was complete as part of the Schwarzwaldbahn (Baden).

In the year 1873 railway lines now ran between Ulm and Sigmaringen, as well as between Tuttlingen and Donaueschingen. The connecting section between Tuttlingen and Sigmaringen was still outstanding.

1873–1890: Closing of the gap under pressure from the military

To close this gap, on the 22nd of May 1875 Württemberg and Baden signed a treaty permitting Württemberg to construct a railway between Sigmaringen and Tuttlingen sometime in the next 15 years, but without setting firm dates for the start of construction.

The next 10 years saw little activity, notwithstanding the fact that many of the towns on the Danube between Sigmaringen and Tuttlingen, as well as the city of Tuttlingen, continued to press for further railway construction. Only an additional 5 kilometers were finished by the Royal Württemberg State Railways between Sigmaringen and Inzigkofen, which was reached in 1878. That particular construction, however, did not have the goal of finishing the Donuatalbahn in mind, but was a section built as part of a different railway construction project: The state of Württemberg had agreed via a treaty with Prussia to build a rail line from Tübingen via the Hohenzollern/Prussian towns of Hechingen, Balingen, and Ebingen, to Sigmaringen. The final section of that line, between Balingen and Sigmaringen, met up with the Donautalbahn near Inzigkofen, and it was decided to extend the Donautalbahn to Sigmaringen. The gap between Inzigkofen and Tuttlingen remained in place.

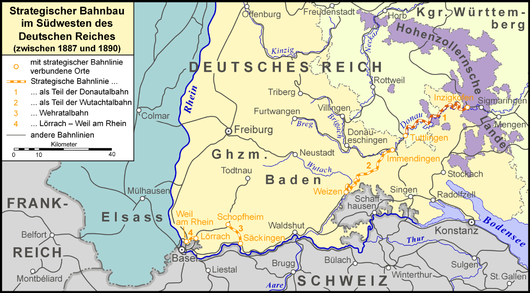

This situation only changed when the German general staff began to take interest in the railway in the middle of the 1880s. The generals remembered well the experience made during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71. Rail transport had played a very significant role in that conflict, and it was assumed that an efficient East-West rail connection would be needed in case of another war with France. In particular, the military had issues with the transport of troops and equipment from Bavaria and Württemberg into the Alsace region across the Rhine, annexed in 1871. A rail connection from the Federal Fort of Ulm (Bundesfestung Ulm) to Belfort was of primary interest. The Hochrheinbahn, which could have served for this purpose, ran through the Canton of Schaffhausen, as well as Basel, in Switzerland. A treaty between Baden and Switzerland, signed in 1865, precluded any military use of this railway, which therefore made this connection unusable in case of war. For this reason, the German general staff initiated plans to build so-called strategic railways, which would avoid going through Swiss territory, and could be used during a military conflict. The construction of the section Inzigkofen–Tuttlingen now became an important part of this rail network for military purposes.

The existing line Ulm–Sigmaringen–Inzigkofen was now to be extended to Tuttlingen, and then to be connected to the existing railway and taken to Immendingen. Further, a new railway, which was to go around the Canton of Schaffhausen to Waldshut, was to be built, which led to the construction of the Wutach Valley Railway. From Waldshut to Säckingen trains would then travel on the Hochrheinbahn in exclusively German territory. In Säckingen trains would then branch off the Hochrheinbahn, which leads to Basel, and take a new railway connection to Schopfheim, which led to the construction of the Wehratalbahn. From Schopfheim to Lörrach the extant Wiesentalbahn was to be used, and a final railway section from Lörrach to Weil am Rhein, which is today known as the Gartenbahn, needed to be built to connect to the existing line to Saint-Louis, Haut-Rhin. There, a connection could be made to Belfort.

Under pressure from the military, construction was undertaken to build these new railways, collectively known as the Kanonenbahnen. In 1887, the general staff contractually agreed to close the gap between Inzigkofen and Tuttlingen, and on the 26th of November 1890, 15 years after the signing of the treaty between Baden and Württemberg, this section was opened for service. The first train was a special train carrying not only the President of Württemberg, Hermann von Mittnacht, and representatives from Baden and Hohenzollern, but also leading generals of the German general staff. The Deutsche Reich (German Empire), whose military had been responsible for the impetus for the construction, financed a large part of the construction expenses. Württemberg, who had a civilian interest in the closing of the gap between Inzigkofen and Tuttlingen, came up with the rest of the funds.

1890–1950: Expansion and destruction

The high expectations, which the military had placed in the Donautalbahn in connection with the other railways in the southwest of Germany, were not met in either World War I or World War II. Up until World War I, there were just a few efforts at expanding the Donautalbahn from the single-track formation it had featured since 1890. In 1912, the connection to the new shunting yard for the city of Ulm, which was located in Söflingen, was expanded by the Royal Württemberg State Railways to twin tracks on the 3-kilometer-long section between Söflingen and Ulm Hauptbahnhof. By 1913, twin tracks had been laid to Herrlingen. Also prior to World War I, the state of Württemberg had planned to expand the section between Tuttlingen and Immendingen, which was also used by long-distance trains on the Gäubahn (Stuttgart–Singen), to feature twin tracks. The advent of World War I put a stop to these plans, and the plans were then cancelled in favor of the construction of a new railway between Tuttlingen and Hattingen in Baden, which had trains from the Gäubahn running on it, starting in 1934. The section of the Donautalbahn between Tuttlingen and Immendingen therefore saw much less traffic, and has been kept as a single-track rail line to today. The expansion of the Schwarzwaldbahn (Baden) to feature twin tracks, which was completed in 1921, had the side effect of expanding the westerly section of the Donautalbahn, between Immendingen and Donaueschingen, to feature twin tracks soon after the end of World War I.

Plans formulated by the Deutsche Reichsbahn for military reasons in 1937 to expand to twin tracks the section between Herrlingen and Immendingen, which had been entirely single-tracked, had strong proponents during the course of World War II, but were not further pursued after the end of the war. After the completion of the Donautalbahn, the railway property around the railway node Ulm were expanded several times, namely between 1899 and 1911 by the Royal Württemberg State Railways, and between 1924 and 1928 by the Deutsche Reichsbahn. In Tuttlingen, which became a railway node with the completion of the section from Inzigkofen, the railway division Stuttgart (Reichsbahndirektion Stuttgart) replaced the entire station and property between 1928 and 1933 with new construction.

The completion of the Höllentalbahn from Donaueschingen to Freiburg in 1901 made possible for the first time a direct connection between Ulm and Freiburg, something that had been under discussion since the 1850s. Starting in 1909, express trains were used to make this trip, which, starting in 1912, sometimes continued on to Colmar in the Alsace region. From 1913, express service was also provided from Munich via the Donautalbahn to Freiburg, which sometimes featured trains with a dining car. The average speed on the line, notwithstanding the use in long-distance connections, remained rather low, at under 50 kilometers per hour (km/h). With the exception of a few service issues during the two wars, service provided by express trains and local service trains, which stopped at every station and halt on the line, remained stable until 1945. This service was initially largely provided by the steam locomotives of the class Württemberg Fc[2], which were heavily used to the mid-1920s, but were then replaced by the Bavarian class P 3/5 H locomotives. After 1929, until the end of World War II, the modern engines of the class DRG Class 24 saw service. Freight service was of little significance on the Donautalbahn due to the lack of industrialization along the route.

Towards the end of World War II, Allied air strikes reached the cities and towns along the railway. In December 1944, Allied bomber squadrons completely destroyed Ulm Hauptbahnhof, as well as the nearby shunting yard at Söflingen. Heavy damage was also caused during the course of 1944 at the stations in Mengen and Tuttlingen. The railway itself escaped most harm, and was serviceable, with some limitations, throughout the war. Heavy damage to the line was then caused by the retreating Wehrmacht, which blew up several railway bridges, disabling through traffic on the Donautalbahn until 1950. Sections of the line were back in service as soon as 1946.

Since 1950: Rebuilding and service improvements

Major improvements in the railway infrastructure on the Donautalbahn were not undertaken, with the exception of the reconstruction of the destroyed railway property at Ulm Hauptbahnhof by 1962, and the electrification of the short section between Immendingen and Donaueschingen, completed in 1977. The Deutsche Bundesbahn did modernize some of the signaling equipment, but also removed many of the passing tracks, and closed the shunting yard at Söflingen as well as several stations experiencing reduced passenger numbers. In the early 1990s, the Bundesbahn sold several railway properties along the line to private companies; for example, large parts of the railway property at the station in Tuttlingen are in private hands, and the entire station hall in Scheer has been privatized. However, closure of sections of the Donautalbahn never did become reality. In the 1950s and 1960s, a collection of older, and an ever-changing variety of steam locomotives saw express train service on the line. Until about 1955 engines of the class Württemberg C dominated the picture, but starting in 1953, the Bavarian class S 3/6 started to replace the Württemberg C, until 1961. Then it was the turn of the class DRG Class 03 until 1971, which started to be replaced from 1966 by the diesel locomotives of the DB Class V 200.

In terms of local service, until 1963 it was initially the Württemberg T 5 leading the trains, which started to be replaced from 1961 by the DRG Class 64. As was the case before the war, freight service was of little significance, and the freight that was carried on the line was handled by the DRB Class 50 steam locomotives until 1976, which started to be replaced, from 1969, by the diesel-powered DB Class V 90. As early as the 1950s, passenger service would sometimes see the use of diesel rail cars. The first diesel-powered vehicle on the Donautalbahn was the VT 60. Starting in 1961, units of the Uerdingen railbus, which dominated traffic in the 1970s, were added into service, and these units were seen up to 1995, but were replaced from 1988 with the diesel units of the DB Class 628, which provided most local passenger service until the turn of the century, and can still be seen now and then on the Donautalbahn today. The diesel engines of the DB Class V 160 led the longer-distance trains starting in 1966, and the DB Class 218 locomotives were added to this service in 1975. The service schedule in the 1950s was similar to the pre-1945 schedule, with the exception that through-traffic from Ulm to France was eliminated, as well as, starting in 1953, the elimination of direct service between Munich and Freiburg, which was replaced in 1954 by the Kleber-Express, using the route Memmingen–Aulendorf–Herbertingen instead of running via Ulm.

The express service offering remained stable until about the 1980s, and the average speed on the line by that time had been increased to 70 km/h. However, the local service schedule was reduced by the Deutsche Bundesbahn by the beginning of the 1990s. In 1988, the Bundesbahn introduced synchronized schedules on the Donautalbahn, which was boosted by a few trains operating outside of the repetitive schedule. Every two hours, services operated as regional express trains from Ulm to Donaueschingen, and on via the Höllentalbahn to Titisee-Neustadt, where a train change to the electrically-operated trains to Freiburg was necessary. In 1996, the DB boosted service by adding other trains, running every two hours between Sigmaringen and Ulm, which then meant trains once an hour on the section between Sigmaringen and Ulm. In 2003, the section between Immendingen and Fridingen was integrated into the Ringzug network, which meant an improvement in service for the western part of the Donautalbahn. By 2004, the Deutsche Bahn AG had expanded the section between Sigmaringen and Ulm to be certified for the use of tilting technology trains.

Operations

Passenger service

Today, service runs every two hours in the form of RegionalExpress (RE) trains between Donaueschingen and Ulm, and this service further takes the Höllentalbahn to Neustadt in the Black Forest. Another set of trains, running every two hours on a schedule in between the first service, travel between Sigmaringen and Ulm, which means trains once an hour on the section between Sigmaringen and Ulm. In the section between Ehingen and Ulm, additional RegionalBahn trains run every hour, boosting service on this section yet further to two trains per hour. These RB trains travel on from Ulm via the Illertalbahn to Memmingen. Similar service is provided between Herbertingen and Sigmaringen, where, in addition to the hourly trains Neustadt-Ulm and Sigmaringen-Ulm, on the section between Sigmaringen and Aulendorf, hourly trains on the Zollernalbbahn further boost service.

On the section between Immendingen and Fridingen, the Donautalbahn was integrated into the Ringzug network. Trains of the Hohenzollerische Landesbahn travel between Rottweil and Tuttlingen on the Gäubahn (Stuttgart–Singen), then on the Donautalbahn to Immendingen, and further on the Wutach Valley Railway to Zollhaus-Blumberg. Under the week, this service is provided hourly, and every two hours on weekends. Between Fridingen and Tuttlingen, train schedules are not synchronized, and individually scheduled trains operate, with no service on weekends on that section. Between May and October, this section is used on the weekend by the Naturpark-Express, which travels between Sigmaringen, Tuttlingen, and Blumberg, and has additional capacity to carry bicycles.

Between Immendingen and Donaueschingen, the service provided every two hours by the RE trains between Neustadt and Ulm is boosted by service provided every two hours by trains on the Schwarzwaldbahn (Baden) between Konstanz and Offenburg, which results in hourly service on that section. Except for the Ringzug trains and the Naturpark-Express, which are operated by the Hohenzollerische Landesbahn, all other service is provided by subsidiaries of the Deutsche Bahn AG. The top speed for long-distance trains from Neustadt to Ulm is still under 70 km/h, and has not improved in recent times.

Freight service

The Hohenzollerische Landesbahn (HzL) uses the Donautalbahn for limited freight service. Between Sigmaringendorf und Ulm the HzL operates freight trains primarily to transport salt.[3] HzL also operates trains to transport freight cars to the tank farm of the energy company Tyczka Totalgaz in Sigmaringen, to a forge in Fridingen, and to a shredding company on Herbertingen. Agricultural equipment manufactured at the factory of the company CLAAS in Bad Saulgau make their way via Mengen across the Donautalbahn. In the district of Alb-Donau, the railway is used by the cement manufacturers Schwenk in Allmendingen and HeidelbergCement in Schelklingen for their transport needs, and the same is true for the paper-and-pulp company Sappi in Ehingen and the company Bohnacker in Rottenacker.[4]

Equipment

The RegionalExpress trains between Neustadt and Ulm and between Ulm and Sigmaringen are largely operated by units of the DBAG Class 611. The Ringzug trains, the RegionalBahn service between Tübingen and Aulendorf, and parts of the RB service between Ehingen and Memmingen, are operated by units of the Stadler Regio-Shuttle RS1. Between Ehingen and Memmingen, units of the DB Class 628 also see service. The Interregio-Express trains of the Zollernalbbahn from Stuttgart via Sigmaringen to Aulendorf, which travel on the Donautalbahn in the section between Sigmaringen and Herbertingen, also use the Class 611 units. The Naturpark-Express is serviced by NE 81 diesel units. For the RegionalExpress trains running between Konstanz and Offenburg, which travel on the Donautalbahn between Donaueschingen and Immendingen, the DB AG uses electric locomotives of the class 146, and double-decker cars. Freight service is primarily handled by DB Class V 90.

Future plans

In 2006, after the shortfall of funds allocated to regionalize local rail service, the section of the Donautalbahn between Inzigkogen and Tuttlingen had been practically put out of service. Today, however, the continued existence of the line is assured[5], and there are even plans to expand sections of the railway. The westerly section of the Donautalbahn, between Donaueschingen and Immendingen, has been discussed in terms of being added to the Ringzug network. Between Sigmaringen and Ulm, the hope is that with the use of tilting technology trains, top speeds of 160 km/h may be reached, which would connect the two points with a trip time of under one hour. Certifying the section between Sigmaringen and Tuttlingen for tilting technology is also being discussed, which would significantly drop the trip time there as well. A study by the name Bodan Rail 2020, which looked into the potential provided by rail service in the greater Bodensee area, namely between southern Germany, the Vorarlberg region in Austria, the north of Switzerland, and Liechtenstein, predicted the tripling or even quadrupling of passenger counts on the Donautalbahn section between Tuttlingen and Ulm, if trip times were reduced by the use of tilting technology.[6]

Shorter trip times, as well as the move of the single-track train crossing points between Tuttlingen and Sigmaringen, would also be the pre-requisites for the development of a Stadtbahn Tuttlingen, which has been under discussion since 2006. This model would use the Donautalbahn, which runs through the city center, as well as residential and industrial areas in the Tuttlingen area, as a city rail line (Stadtbahn), and would connect the communities east of Tuttlingen, which are poorly served by the Ringzug, to this network.[7] Probably the most ambitious plans are the ones for a S-Bahn network Ulm/Neu-Ulm. These plans, extant since the 1990s, envision the construction of a new rail line, which would branch off the existing Donautalbahn in Ehingen (Donau) and go to Erbach (Donau) on the Südbahn. This new railway would see only the RegionalExpress trains going from Ulm via Sigmaringen to Neustadt (Schwarzwald), which would significantly cut the trip times. The old section between Ehingen via Blaubeuren, which is densely populated, would be served by a new S-Bahn in the Ulm area. The new section has been tagged with a cost of 75 million Euros. The regional association Donau-Iller is in favor of these plans, which are opposed by the state government of the state of Baden-Württemberg.[8]

Listing in the Kursbuch

The Donautalbahn cannot be found under a single listing in the Kursbuchstrecke (KBS) listing of the Deutsche Bahn.

- KBS 755 includes the entire Donautalbahn route, but also includes large portions of the Höllentalbahn. In addition, listings under KBS 755 do not list many of the services provided on the Donautalbahn, such as the service Ehingen (Donau)–Ulm–Memmingen, or the Ringzug services, which are found in other KBS listings.

- KBS 756 includes all services on the section Ehingen–Ulm. In addition, all of the services provided on the Illertalbahn on the section Ulm–Memmingen are also included, plus the services on the Schwäbische Albbahn on the section Münsingen–Schelklingen.

- KBS 759.2, which is the primary KBS for the Schwäbische Albbahn, also includes the services on the Donautalbahn in the section Schelklingen–Ulm.

- KBS 766, which is the primary KBS for the Zollernalbbahn, covers all service offerings of both the Zollernalbbahn and the Donautalbahn in the section Herbertingen–Sigmaringen.

- KBS 743, which covers parts of the Gäubahn, the Donautalbahn, as well as all of the services on the Wutach Valley Railway, covers the Donautalbahn section from Fridingen to Immendingen, and also covers the Ringzug services.

- KBS 720, which is the primary KBS for the Schwarzwaldbahn (Baden), covers the Donautalbahn section Donaueschingen–Immendingen.

- KBS 740, which is the primary KBS of the Gäubahn (Stuttgart–Singen), covers the section Immendingen–Tuttlingen of the Donautalbahn.

See also

- History of the railway in Württemberg

- Royal Württemberg State Railways

- Grand Duchy of Baden State Railway

- Danube Valley Railway (Bavaria), the railway line from Ulm to Regensburg

- Strategic railway

References

- ^ http://steinbeis.st.funpic.de/ "Wer war Ferdinand von Steinbeis?" an audio-visual biography by Siegfried Gmeiner

- ^ The types of engines used on the Donautalbahn in its early days are very difficult to ascertain. Especially before 1894, the available literature does not specify the locomotives used. After this time, Hans-Wolfgang Scharf (see Literature) attempts to determine the engines in use by looking at the classes of locomotives being kept in train depots on and near the Donautalbahn.

- ^ Bahn-Report 5/2007, p. 79

- ^ Report in the Südwestpresse of the 9th of November 2007 about the engineer strike of 2007 [1]

- ^ Stuttgarter Zeitung of the 27th of September 2006

- ^ please see CD-ROM (full version) of the Bodan Rail 2020-Studie, particularly Plan 6.7 and Plan 9.14. The study compares passenger counts of 1997 with predicted numbers of 2020. The study was concluded in 2001.

- ^ Local version of the Schwäbischen Zeitung Tuttlingen (Gränzbote) of the 21st of August 2006

- ^ detailed article in the Südwestpresse of the 21st of February 2007, the position of the state government is found here and here

Literature

- Willi Hermann and others: Die Donautalbahn (Gesammelte Aufsätze zur Fridinger Geschichte, Bd. 16, published by the Heimatkreis Fridingen e. V.). Tuttlingen: Typodruck, 2004.

- Richard Leute: 100 Jahre Donautalbahn; in: „Tuttlinger Heimatblätter“ (1988), p. 8–26. (Other issues of the Tuttlinger Heimatblätter also discuss the Donautalbahn in the past decades.)

- Hans-Wolfgang Scharf: Die Eisenbahn im Donautal und im nördlichen Oberschwaben. EK-Verlag, Freiburg [Breisgau] 1997, ISBN 3-88255-765-6 (out-of-print; this is the main source, upon which the article is largely based.)

- Zweckverband Ringzug Schwarzwald-Baar-Heuberg (Hrsg.), Der 3er Ringzug: Eine Investition für die Zukunft der Region Schwarzwald-Baar-Heuberg, Villingen-Schwenningen 2006. (includes descriptions of all of the Donautalbahn properties between Immendingen-Zimmern and Fridingen) Information beim Zweckverband

External links

- Route description at www.ulmereisenbahnen.de (Fahrzeugeinsatz, Bilder)

- Report on the upgrade for tilting trains on the Ulm–Sigmaringen section

- Tunnelportale.de/lb/inhalt/ Tunnelportale/4540.html Tunnels between Ulm and Sigmaringen

- Tunnelportale.de/lb/inhalt/ Tunnelportale/4660.html Tunnels between Inzigkofen and Tuttlingen

- Extract from the DR 1944/45 timetable – Danube Valley Railway

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.