- Hermann's tortoise

-

Hermann's tortoise

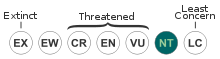

Testudo hermanni hermanni on Majorca Conservation status Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Reptilia Order: Testudines Suborder: Cryptodira Family: Testudinidae Genus: Testudo (disputed) Species: T. hermanni Binomial name Testudo hermanni

Gmelin, 1789

Range map.

Western green population is hermanni, eastern blue boettgeri and red hercegovinensis.Synonyms Eurotestudo hermanni

Testudo hercegovinensis

and see textHermann's tortoise (Testudo hermanni) is one of five tortoise species traditionally placed in the genus Testudo, which also includes the well-known Marginated tortoise (T. marginata), Greek tortoise (T. graeca), and Russian tortoise (T. horsfieldii), for example. Three subspecies are known: the Western Hermann's tortoise (T. h. hermanni), the Eastern Hermann's tortoise (T. h. boettgeri) and Dalmatian tortoise (T. h. hercegovinensis). Sometimes mentioned subspecies T. h. peleponnesica is not yet confirmed to be genetically different to T. h. boettgeri.

Contents

Geographic range

Testudo hermanni can be found throughout southern Europe. The western population (hermanni) is found in eastern Spain, southern France, the Baleares islands, Corsica, Sardinia, Sicily, south and central Italy (Tuscany). The eastern population (boettgeri) inhabits Serbia, Macedonia, Romania, Bulgaria, Albania, and Greece, while hercegovinensis populates coasts of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia and Montenegro.

Subspecies

Testudo hermanni hermanni (Spain)

Testudo hermanni hercegovinensis (Bosnia)

Testudo hermanni boettgeri (Greece/Turkey)

Description and systematics

Hermann's tortoises are small to medium sized tortoises that come from southern Europe. Young animals, and some adults, have attractive black and yellow patterned carapaces, although the brightness may fade with age to a less distinct gray, straw or yellow coloration. They have a slightly hooked upper jaw and, like other tortoises, possess no teeth,[2] just a strong, horny beak.[3] Their scaly limbs are greyish to brown, with some yellow markings, and the tail bears a spur (a horny spike) at the tip.[3] Adult males have particularly long and thick tails,[4] and a well developed spur, distinguishing them from females.[3]

The eastern subspecies Testudo hermanni boettgeri is much larger than the west, reaching sizes up to 28 cm (11 inches) in length. A specimen of this size may weigh 3-4 kg (6-9 lb). T. h. hermanni rarely grow larger than 18 cm (7.5 inches). Some adult specimens are as small as 7 cm (3 inches).

In 2006 it was suggested to move Hermann's tortoise to the genus Eurotestudo and to bring the subspecies to the rank of species (Eurotestudo hermanni and Eurotestudo boettgeri).[5] Though there are some indications that this might be correct,[6] the data at hand is not unequivocally in support and the relationships between Hermann's and the Russian tortoise among each other and to the other species placed in Testudo are not robustly determined. Hence it seems doubtful that the new genus will be accepted for the time being. The elevation of the subspecies to full species was tentatively rejected under the Biological Species Concept at least, as there still seems significant gene flow.[7]

It was also noted that the rate of evolution as measured by mutations accumulating in the mtDNA differs markedly, with the eastern populations having evolved faster. This is apparently due to stronger fragmentation of the population on the mountainous Balkans during the last ice age. While this has no profound implications for taxonomy of this species - apart from suggesting that two other proposed subspecies are actually just local forms at present -, it renders the use of molecular clocks in Testudo even more dubious and unreliable than they are for turtles in general[8].[7]

Testudo hermanni hermanni

The subspecies Testudo hermanni hermanni includes the former subspecies robertmertensi and has a number of local forms. It has a highly arched shell with an intensive coloration, with its yellow coloration making a strong contrast to the dark patches. The colors wash out somewhat in older animals, but the intense yellow is often maintained. The underside has two connected black bands along the central seam.

The coloration of the head ranges from dark green to yellowish, with isolated dark patches. A particular characteristic is the yellow fleck on the cheek found in most specimens, although not in all; robertmertensi is the name of a morph with very prominent cheek spots. Generally, the forelegs have no black pigmentation on their undersides. The base of the claws is often lightly colored. The tail in males is larger than in females and possesses a spike. Generally the shell protecting the tail is divided. A few specimens can be found with undivided shells, similar to the Greek tortoise.

Testudo hermanni boettgeri

The subspecies hercegovinensis (Balkans coast) and the local peloponnesica (SW Peloponnesus coast) are now included here; they constitute local forms that are not yet geographically or in other ways reproductively isolated and apparently derive from relict populations of the last ice age.[7] The Eastern Hermann's tortoise also has an arched, almost round carapace, but some are notably flatter and more oblong. The coloration is brownish with a yellow or greenish hue and with isolated black flecks. The coloring tends to wash out quite strongly in older animals. The underside is almost always solid horn color, and has separate black patches on either side of the central seam.

The head is brown to black, with fine scales. The forelegs similarly possess fine scales. The limbs generally have five claws, which are darkly colored at their base. The hindlegs are noticeably thicker than the forelegs, almost plump. The particularly strong tail ends in a spike, which may be very large in older male specimens. Females have noticeably smaller tailspikes, which are slightly bent toward the body.

-

Adult female, Bulgaria

Ecology

Early in the morning, the animals leave their nightly shelters, which are usually hollows protected by thick bushes or hedges, to bask in the sun and warm their bodies. They then roam about the Mediterranean meadows of their habitat in search of food. They determine which plants to eat by the sense of smell. (In captivity, they are known to eat dandelions, clover and lettuce as well as the leaves, flowers, and pods of almost all legumes.) In addition to leaves and flowers, the animals eat fruits as supplementary nutrition. They only eat a small amount of fruit, just enough to satisfy themselves.

Around midday, the sun becomes too hot for the tortoises, so they return to their hiding places. They have a good sense of direction to enable them to return. Experiments have shown that they also possess a good sense of time, the position of the sun, the magnetic lines of the earth, and for landmarks.[citation needed] In the late afternoon, they leave their shelters again and return to feeding.

In late February, Hermann’s tortoises emerge from under bushes or old rotting wood, where they spend the winter months hibernating, buried in a bed of dead leaves.[3] Immediately after surfacing from their winter resting place, Hermann’s tortoises commence courtship and mating.[3] Courtship is a rough affair for the female, who is pursued, rammed and bitten by the male, before being mounted. Aggression is also seen between rival males during the breeding season, which can result in ramming contests.[4]

Between May and July, female Hermann’s tortoises deposit between two and twelve eggs into flask-shaped nests dug into the soil,[4] up to ten centimetres deep.[3] Most females lay more than one clutch each season.[4] The pinkish-white eggs are incubated for around 90 days and, like many reptiles,[4] the temperature at which the eggs are incubated determines the hatchlings sex. At 26 degrees Celsius, only males will be produced, while at 30 degrees Celsius, all the hatchlings will be female.[3] Young Hermann’s tortoises emerge just after the start of the heavy autumn rains in early September, and spend the first four or five years of their lives within just a few metres of their nest.[4] If the rains do not come, or if nesting took place late in the year, the eggs will still hatch but the young will remain underground and not emerge until the following spring. Until the age of six or eight, when the hard shell becomes fully developed, the young tortoises are very vulnerable to predators, and may fall prey to rats, badgers, magpies, foxes, wildboar and many other animals. If they survive these threats, then Hermann’s tortoises may live for around 30 years.[3]

Breeding

Breeding and upbringing of Hermann's tortoise is quite easy if it is kept in species-appropriate environment. The European Studbook Foundation maintains stud books for both subspecies. With the help of Uva/Uvb emitting bulbs (such as Repti Glo and Creature World) the correct environment for breeding can be created and bring tortoise's into perfect breeding condition.

In captivity

Sanctuaries

There are several tortoise sanctuaries in Europe such as "Carapax" in southern Tuscany, and "Le Village Des Tortues" in the South of France (near Gonfaron). These sanctuaries rescue injured tortoises whilst also taking in unwanted pets. These two sanctuaries specialise in Hermann's tortoises.

Outdoors

In order to keep Hermann's tortoise in a temperate climate, the pen must be placed in a very sunny location. The most important part of the pen is a tortoise house that they can use as a shelter. This should be a weatherproof box with an openable roof and an entry way for the animals. The floor should consist of soil as in the wild to enable burying and thermoregulation. Their life pattern in captivity is the same as in the wild. They leave the house in the early morning to warm themselves and then begin to eat. They should be provided with a wide range of edible materials. They eat for about an hour before returning to the house. In the late afternoon, they come out again for a second meal. They can be kept outdoors approximately from mid-March to the end of October. The pen should normally be constructed from natural stones.

The tortoise house must be relatively large, some 0.4 m³ (14 ft³) in size. It should be made of wood and have no floor to enable the tortoise to thermoregulate its own body temperature via burying itself. Other materials will produce a house that is too hot or too cold. There should be a heat lamp operated by thermostatic control

Indoors

Hatchlings and young specimens can be kept indoors, and although a vivarium is often offered as suitable accommodation, the humidity in such an enclosure can reach levels much higher than commonly found in the wild, leading to respiratory problems. A clamp lamp should be fastened to it so that a 40 to 60-watt reflector bulb is some 20 cm (8 in) above the level of the gravel of the enclosure. The bulb is turned on in the morning so that the animals can bask and then feed, a source of UV must also be provided, in the form of a HighUV fluorescent tube, or similar. The animals should also regularly be put into sunlight in the summer outdoors to provide them with necessary ultraviolet radiation, placing a tortoise on a window sill in winter will not provide the required level of UV, as glass will filter out UV.

The animals must be allowed to self regulate their temperature. This can be achieved by providing a temperature gradient in the enclosure, ranging from around 33 °C at the hot end to 18 °C at the cool end. The animal will then choose a position in the enclosure to reach its desired temperature

Hibernation

In nature, the animals dig their nightly shelters out and spend the relatively mild Mediterranean winters there. During this time, the heart rate and breathing rate drop notably. Domestic animals can be kept in the basement in a roomy rodent-proof box with a thick layer of dry leaves. The temperature should be around 5 degrees C As an alternative, the box can be stored in a refrigerator. For this method to be used, the fridge should be in regular day to day use, to permit air flow. During hibernation, it is vital that the ambient temperature not fall below zero. Full-grown specimens may sleep 4–5 months at a time.

Hatching Hermann's tortoise

See also

- Mediterranean tortoise

- List of reptiles of Italy

Footnotes

- ^ "Testudo hermanni". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2010.4. International Union for Conservation of Nature. 2004. http://www.iucnredlist.org/apps/redlist/details/21648. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ^ Burnie, D. (2001). Animal. London: Dorling Kindersley.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bonin, F. (2006). Turtles of the World. London: A&C Black Publishers Ltd. with Devaux, B. and Dupré, A.

- ^ a b c d e f Ernst, C.H., C.H. (1997). Turtles of the World. Netherlands: ETI Information Systems Ltd. with Altenburg, R.G.M. and Barbour, R.W.

- ^ de Lapparent de Broin (2006)

- ^ e.g. Fritz et al. (2005)

- ^ a b c Fritz et al. (2006)

- ^ Avise et al. (1992), van der Kuyl et al. (2005)

References

This article incorporates text from the ARKive fact-file "Hermann's tortoise" under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License and the GFDL.

- Avise, John C.; Bowen, Brian W.; Lamb, Trip; Meylan, Anne B. & Bermingham, Eldredge (1992): Mitochondrial DNA evolution at a turtle's pace: evidence for low genetic variability and reduced microevolutionary rate in the Testudines. Mol. Biol. Evol. 9(3): 457-473. PDF fulltext

- de Lapparent de Broin, France; Bour, Roger; Parham, James F. & Perälä, Jarmo (2006): Eurotestudo, a new genus for the species Testudo hermanni Gmelin, 1789 (Chelonii, Testudinidae). [English with French abstract] C. R. Palevol 5(6): 803-811. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2006.03.002 PDF fulltext

- Fritz, Uwe; Kiroký, Pavel; Kami, Hajigholi & Wink, Michael (2005): Environmentally caused dwarfism or a valid species - Is Testudo weissingeri Bour, 1996 a distinct evolutionary lineage? New evidence from mitochondrial and nuclear genomic markers. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 37(2): 389–401. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2005.03.007 PDF fulltext

- Fritz, Uwe; Auer, Markus; Bertolero, Albert; Cheylan, Marc; Fattizzo, Tiziano; Hundsdörfer, Anna K.; Sampayo, Marcos Martín; Pretus, Joan L.; Široký, Pavel & Wink, Michael (2006): A rangewide phylogeography of Hermann's tortoise, Testudo hermanni (Reptilia: Testudines: Testudinidae): implications for taxonomy. Zool. Scripta 35(5): 531-548. doi:10.1111/j.1463-6409.2006.00242.x PDF fulltext

- van der Kuyl, Antoinette C.; Ballasina, Donato L. Ph. & Zorgdrager, Fokla (2005): Mitochondrial haplotype diversity in the tortoise species Testudo graeca from North Africa and the Middle East. BMC Evol. Biol. 5: 29. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-5-29 (HTML/PDF fulltext + supplementary material)

- Henley, Jon (December 9, 2005). "Rare tortoise puts brakes on high-speed train link". The Guardian. http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2005/dec/09/france.conservationandendangeredspecies. Retrieved 2008-07-22.

External links

Tortoise family of turtles (Testudinidae) Genus

Aldabrachelys Astrochelys Chelonoidis Chersina Cylindraspis† Geochelone Gopherus Homopus Beaked cape tortoise · Berger's cape tortoise · Boulenger's cape tortoise · Karoo cape tortoise · Speckled padloper tortoiseIndotestudo Elongated tortoise · Forsten's tortoise · Travancore tortoiseKinixys Bell's hinge-back tortoise · Forest hinge-back tortoise · Home's hinge-back tortoise · Lobatse hinge-back tortoise · Natal hinge-back tortoise · Speke's hinge-back tortoiseMalacochersus Manouria Psammobates Pyxis Stigmochelys Testudo Hermann's tortoise · Kleinmann's tortoise · Marginated tortoise · Russian tortoise · Spur-thighed tortoisePhylogenetic arrangement of turtles based on turtles of the world 2010 update: annotated checklist of taxonomy, synonymy, distribution and conservation status. Key: †=extinct. 1=classification unclearOrder Testudines (turtles) Suborder SuperfamilySubfamily

Cryptodira Caretta · Chelonia · Eretmochelys · Lepidochelys · NatatorDermochelysDermatemydidaeDermatemysStaurotypinaeBatagur · Cuora · Cyclemys · Geoclemys · Geoemyda · Hardella · Heosemys · Leucocephalon · Malayemys · Mauremys · Melanochelys · Morenia · Notochelys · Orlitia · Pangshura · Rhinoclemmys · Sacalia · Siebenrockiella · VijayachelysAldabrachelys · Astrochelys · Chelonoidis · Chersina · Cylindraspis · Geochelone · Gopherus · Homopus · Indotestudo · Kinixys · Malacochersus · Manouria · Psammobates · Pyxis · Stigmochelys · TestudoTrionychiaCarettochelyidaeCarettochelysTrionychinaePleurodira ChelidinaeChelodininaeHydromedusinaePhylogenetic arrangement based on turtles of the world 2010 update: annotated checklist. Extinct turtles not included.

See also List of Testudines families

Portal ·

Portal ·  WikiProjectCategories:

WikiProjectCategories:- IUCN Red List near threatened species

- Testudo

- Reptiles of Europe

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.