- Costero

-

Costero

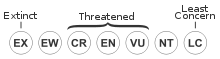

Size comparison against an average human Conservation status Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Mammalia Order: Cetacea Family: Delphinidae Genus: Sotalia Species: S. guianensis Binomial name Sotalia guianensis

(van Bénéden, 1864)

Costero's range (coastal–blue fill) The Costero (Sotalia guianensis) is found in the coastal waters to the north and east of South America. The common name "costero" has been suggested by Caballero and colleagues[2] due to the species' affinity for coastal habitats. The Costero is a member of the oceanic dolphin family (Delphinidae). Physically it resembles the Bottlenose Dolphin. However, this species is sufficiently different from the Bottlenose Dolphin that it is given its own genus, Sotalia. It is also known as the Guyana dolphin.

Contents

Description

The Costero is frequently described as looking similar to the bottlenose dolphin. However it is typically smaller, at only up to 210 cm length. The dolphin is colored light to bluish grey on its back and sides. The ventral region is light gray. The dorsal fin is typically slightly hooked. The beak is well-defined and of moderate length.

Researchers have recently shown that the Costero has a electroreceptive sense, and speculate this may also be the case for other toothed whales.[3]

Taxonomy

Although described as species distinct from the Tucuxi Sotalia fluviatilis by Pierre-Joseph van Bénéden in 1864, the Costero Sotalia guianensis has subsequently been synonymized with Sotalia fluviatilis with the two species being treated as subspecies, or marine and freshwater varieties.[4] The first to reassert differences between these two species was a three-dimensional morphometric study of Monteiro-Filho and colleagues.[5] Subsequently a molecular analysis by Cunha and colleagues[6] unambiguously demonstrated that Sotalia guianensis was genetically differentiated from Sotalia fluviatilis. This finding was reiterated by Caballero and colleagues[2] with a larger number of genes. The existence of two species has been generally accepted by the scientific community, however, the IUCN still treats both species as a single species Sotalia fluviatilis.

Distribution

The Costero is found close to estuaries, inlets and other protected shallow water areas around the eastern and northern South America coast. It has been reported as far south as southern Brazil and north as far as Nicaragua. One report exists of an animal reaching Honduras.

Behavior

This species forms small groups of about 10-15 individuals, occasionally up to 30 and swim in tight-knit groups, suggesting a highly developed social structure. They are quite active and may jump clear of the water (a behavior known as breaching), somersault, spy-hop or tail-splash. They are unlikely however to approach boats. They feed on a wide variety of fish. Studies of growth layers suggest that the species can live up to 30 years.

In December 2006, researchers from the Southern University of Chile and the Rural Federal University of Rio de Janeiro witnessed attempted infanticide by a group of costero dolphins in Sepetiba Bay, Brazil.[7] A group of six adults separated a mother from her calf, four then keeping her at bay by ramming her and hitting her with their flukes. The other two adults rammed the calf, held it under water then threw it into the air and held it under water again. The mother was seen again in a few days, but not her calf. Since females become sexually receptive within a few days of losing a calf, and the group of attacking males was sexually interested in the female, it is possible that the infanticide occurred for this reason.[8] Infanticide has been reported twice before in bottlenose dolphins, but is thought to be generally uncommon among cetaceans.[8]

Conservation

The Costero appears to be relatively common, however, it gets frequently entangled in nets of the coastal fishing fleets. It is estimated that at least 2,000 animals are killed by entanglement per year in the Amazon River delta region.[9] Many of these animals are used as shark fishing bait, and their organs are sold as fetishes.[10] Another major problem in some areas are collisions with boats. Possible natural predators are the Orca and the bull shark.

The Guiana dolphin is listed on Appendix II[11] of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS). It is listed on Appendix II[11] as it has an unfavourable conservation status or would benefit significantly from international co-operation organised by tailored agreements.

References

- ^ Reeves, R.R., Crespo, E.A., Dans, Jefferson, T.A., Karczmarski, L., Laidre, K., O’Corry-Crowe, G., Pedraza, S., Rojas-Bracho, L., Secchi, E.R., Slooten, E., Smith, B.D., Wang, JY. & Zhou, K. (2008). Sotalia. In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Downloaded on 25 February 2009. Includes a lengthy justification of the data deficient category. Treats Sotalia guianensis and Sotalia fluviatilis as subspecies.

- ^ a b Caballero, S., F. Trujillo, J. A. Vianna, H. Barrios-Garrido, M. G. Montiel, S. Beltrán-Pedreros, M. Marmontel, M. C. Santos, M. R. Rossi-Santos, F. R. Santos, and C. S. Baker (2007). "Taxonomic status of the genus Sotalia: species level ranking for "tucuxi" (Sotalia fluviatilis) and "costero" (Sotalia guianensis) dolphins". Marine Mammal Science 23: 358–386. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2007.00110.x.

- ^ Nicole U. Czech-Damal, Alexander Liebschner, Lars Miersch, Gertrud Klauer, Frederike D. Hanke, Christopher Marshall, Guido Dehnhardt and Wolf Hanke (2011). "Electroreception in the Guiana dolphin (Sotalia guianensis)". Proc. R. Soc. B. doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.1127.

- ^ Borobia, M., S. Siciliano, L. Lodi, and W. Hoek (1991). "Distribution of the South American dolphin Sotalia fluviatilis". Canadian Journal of Zoology 69: 1024–1039. doi:10.1139/z91-148.

- ^ Monteiro-Filho, E.L.D.A., L. Rabello-Monteiro, and S.F.D. Reis (2008). "Skull shape and size divergence in dolphins of the genus Sotalia: A morphometric tridimensional analysis". Journal of Mammalogy 83: 125–134. doi:10.1644/1545-1542(2002)083<0125:SSASDI>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Cunha, H.A., V.M.F. da Silva, J. Lailson-Brito Jr., M.C.O. Santos, P.A.C. Flores, A.R. Martin, A.F. Azevedo, A.B.L. Fragoso, R.C. Zanelatto, and A.M. Solé-Cava (2005). "Riverine and marine ecotypes of Sotalia dolphins are different species". Marine Biology 148: 449–457. doi:10.1007/s00227-005-0078-2.

- ^ "Dolphins seen trying to kill calf". BBC News. 18 May 2009. http://news.bbc.co.uk/earth/hi/earth_news/newsid_8048000/8048288.stm. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ a b Nery, M. F., and S. M. Simão (2009). "Sexual coercion and aggression towards a newborn calf of marine tucuxi dolphins (Sotalia guianensis)". Marine Mammal Science 25: 450–454. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2008.00275.x.

- ^ Beltrán, S. (1998) Captura accidental de Sotalia fluviatilis (Gervais, 1853) na pescaria artesanal do estuário Amazônico. Masters Thesis in Biology. Universidade Federal do Amazonas, Manaus, AM, Brazil

- ^ Gravena, W., T. Hrbek, V.M.F. da Silva, and I.P. Farias (2008). "Amazon River dolphin love fetishes: From folklore to molecular forensics". Marine Mammal Science 24: 969–978. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2008.00237.x.

- ^ a b "Appendix II" of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS). As amended by the Conference of the Parties in 1985, 1988, 1991, 1994, 1997, 1999, 2002, 2005 and 2008. Effective: 5th March 2009.

- Flach L, Flach PA, Chiarello AG (2008) Density, abundance and distribution of the Guiana dolphin (Sotalia guianensis van Benéden, 1864) in Sepitiba Bay, southeast Brazil. J Cetacean Res Manage 10:31-36.

- Rosas FCW, Monteiro-Filho ELA (2003) Reproduction of the estuarine dolphin (Sotalia guianensis) on the coast of Parana, Southern Brazil. J Mammal 83: 507-515

External links

- Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society (WDCS)

- Convention on Migratory Species page on the Guiana dolphin

Categories:- IUCN Red List data deficient species

- Oceanic dolphins

- Mammals of South America

- Mammals of Brazil

- Megafauna of South America

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.