- Boll weevil

-

Boll Weevil

Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Arthropoda Class: Insecta Order: Coleoptera Family: Curculionidae Genus: Anthonomus Species: A. grandis Binomial name Anthonomus grandis

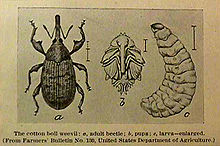

Boheman, 1843The boll weevil (Anthonomus grandis) is a beetle measuring an average length of six millimeters, which feeds on cotton buds and flowers. Thought to be native to Central America, it migrated into the United States from Mexico in the late 19th century and had infested all U.S. cotton-growing areas by the 1920s, devastating the industry and the people working in the American south. During the late 20th century it became a serious pest in South America as well. Since 1978, the Boll Weevil Eradication Program in the U.S. has allowed full-scale cultivation to resume in many regions.

Contents

Life cycle

Adult weevils overwinter in well-drained areas in or near cotton fields after diapause. They emerge and enter cotton fields from early spring through midsummer, with peak emergence in late spring, and feed on immature cotton bolls. The female lays about 200 eggs over a 10-12 day period. The oviposition leaves wounds on the exterior of the flower bud. The eggs hatch in three to five within the cotton squares for eight to ten days, then pupate. The pupal stage lasts five to seven days. The life cycle from egg to adult spans about three weeks during the summer. Under optimal conditions there may be eight to 10 generations per season. According to the book "From Can See to Can't" by Thad Sitton and Dan Utley, "Under ideal conditions for reproduction--which fortunately seldom existed--the progeny of a single pair of weevils emerging in the spring could reach something like 134 million before the coming of frost.

Boll weevils will begin to die at temperatures at or below 23 degrees Fahrenheit. Research at the University of Missouri indicates they cannot survive more than an hour at 5 degrees Fahrenheit. The insulation offered by leaf litter, crop residues, and snow may enable the beetle to survive when air temperatures drop to these levels.

Other limitations on boll weevil populations include extreme heat and drought. Its natural predators include fire ants, insects, spiders, birds, and a parasitic wasp, Catolaccus grandis. The insects at times engage in what seems to be almost suicidal behavior by emerging from diapause before cotton buds are available.

Infestation

The insect crossed the Rio Grande near Brownsville, Texas to enter the United States from Mexico in 1892[1] and reached southeastern Alabama in 1915. By the mid 1920s it had entered all cotton growing regions in the U.S., travelling 40 to 160 miles per year. It remains the most destructive cotton pest in North America. Mississippi State University has estimated that since the boll weevil entered the United States it has cost U.S. cotton producers about $13 billion, and in recent times about $300 million per year.[1]

The boll weevil contributed to the economic woes of Southern farmers during the 1920s, a situation exacerbated by the Great Depression in the 1930s.

The Library of Congress American Memory Project contains a number of oral history materials on the boll weevil's impact.[2] In one of the project's features, a 1939 interview for the Federal Writers' Project, South Carolina native Mose Austin recalled that his employer was adamant. "He don't want nothin' but cotton planted on de place; dat he in debt and hafter raise cotton to git de money to pay wid." Austin let out a long guffaw before recounting, "De boll weevil come...and, bless yo' life, dat bug sho' romped on things dat fall." Austin remembered that the following spring, his employer insisted on planting cotton in spite of warnings from his wife, his employees, and government agricultural experts:

- De cotton come up and started to growin', and, suh, befo' de middle of May I looks down one day and sees de boll weevil settin' up dere in de top of dem little cotton stalks waitin' for de squares to fo'm. So all dat gewano us hauled and put down in 1922 made nuttin' but a crop of boll weevils. [3]

The next year, Austin's employer tried the same ill-fated experiment. Ultimately, the man lost his farm and moved with his disgruntled wife to California.

The boll weevil infestation has been credited with bringing about economic diversification in the southern US, including the expansion of peanut cropping. The citizens of Enterprise, Alabama erected the Boll Weevil Monument in 1919, perceiving that their economy had been overly dependent on cotton, and that mixed farming and manufacturing were better alternatives.

The boll weevil appeared in Venezuela in 1949 and in Colombia in 1950.[4] The Amazon Rainforest was thought to present a barrier to its further spread, but it was detected in Brazil in 1983, and it is estimated that about 90% of the cotton farms in Brazil are now infested. During the 1990s the weevil spread to Paraguay and Argentina. The International Cotton Advisory Committee (ICAC) has proposed a control program similar to that used in the U.S.[4]

Control

Following World War II the development of new pesticides such as DDT enabled U.S. farmers again to grow cotton as an economic crop. DDT was initially extremely effective, but US weevil populations developed resistance by the mid 1950s.[5] Methyl parathion, malathion, and pyrethroids were subsequently used, but environmental and resistance concerns arose as they had with DDT and control strategies changed.[5] In 1978 a test was conducted in North Carolina to determine feasibility of eradicating the weevil from the growing areas. Based on the success of this, area-wide programs were begun in the 1980s to eradicate the insect from whole regions. These are based on cooperative effort by all growers together with the assistance of the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). The program has been successful in eradicating weevils from Virginia and the Carolinas, Georgia, Florida, south Alabama, California, and Arizona. Efforts are ongoing to eradicate the weevil from the rest of the United States. Continued success is also based on prohibition of unauthorized cotton growing, outside of the program, and constant monitoring for any recurring outbreaks.

In the 1980s, entomologists at Texas A&M have pointed to the spread of another invasive pest, fire ants, as a factor in the weevils' population decline.[6]

Other avenues of control that have been explored include weevil-resistant strains of cotton, [7] the parasitic wasp Catolaccus grandis,[8] the fungus Beauveria bassiana,[9] and the Chilo iridescent virus. Genetically engineered Bt cotton is not protected from the boll weevil.[10]

Further reading

- Lange, Fabian, Alan L. Olmstead, and Paul W. Rhode, “The Impact of the Boll Weevil, 1892–1932,” Journal of Economic History, 69 (Sept. 2009), 685–718.

See also

- Lixus concavus, the Rhubarb curculio weevil

- Female Sperm Storage

References

- ^ a b Mississippi State University. Economic impacts of the boll weevil "History of the Boll Weevil in the United States". http://www.bollweevil.ext.msstate.edu/webpage_history.htm Economic impacts of the boll weevil.

- ^ The American Memory Project - Boll weevils

- ^ "Always Agin It" Place Chapin, South Carolina, John L. Dove, interviewer, January 24, 1939. American Life Histories, 1936–1940

- ^ a b ICAC. "Integrated Pest Management Of The Cotton Boll Weevil In Argentina, Brazil, And Paraguay". http://www.icac.org/Projects/CommonFund/Boll/proj_03_proposal.pdf.

- ^ a b Timothy D. Schowalter (31 May 2011). Insect Ecology: An Ecosystem Approach. Academic Press. p. 482. ISBN 978-0-12-381351-0. http://books.google.com/books?id=2KzokTLIysQC&pg=PA482. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ D. A. Fillman and W. L. Sterling. "Fire ant predation on the boll weevil". BioControl: Volume 28, Number 4 / December, 1983. http://www.springerlink.com/content/pl4557w722v04q54/.

- ^ Hedin, P. A. and McCarty, J. C.. "Weevil-resistant strains of cotton". Journal of agricultural and food chemistry:1995, vol. 43, no10, pp. 2735-2739 (19 ref.). http://cat.inist.fr/?aModele=afficheN&cpsidt=2906042.

- ^ Juan A. Morales-Ramos. "Catolaccus grandis (Burks) (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae)". Biological Control: a guide to Natural Enemies in North America. http://www.nysaes.cornell.edu/ent/biocontrol/parasitoids/catolaccus_grandis.html.

- ^ Biological controls of the boll weevil

- ^ Bt susceptibility of insect species

External

External links

Categories:- Curculioninae

- Agricultural pest insects

- Cotton

- Animals described in 1843

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.