- Charles Young (United States Army)

-

This article is about the United States Army officer. For other uses of the name, see Charles Young (disambiguation).

Charles Young Born March 12, 1864

May's Lick, KentuckyDied January 8, 1922 (aged 57)

NigeriaAllegiance United States of America Years of service 1884–1922 Rank Colonel Charles Young (March 12, 1864 - January 8, 1922) was the third African American graduate of West Point, the first black U.S. national park superintendent, first black military attaché, first black to achieve the rank of colonel, and highest-ranking black officer in the United States Army until his death in 1922.

Contents

Early life and education

Charles Young was born in 1864 into slavery to Gabriel Young and Arminta Bruen in May's Lick, Kentucky, a small village near Maysville, but he grew up a free person.[1] His father Gabriel escaped from slavery, in 1865 going across the Ohio River to Ripley, Ohio to enlist as a private in the Fifth Regiment of the Colored Artillery (Heavy) Volunteers during the American Civil War. Accounts differ as to whether he took his wife and child with him then.[1] His service earned him and his wife freedom. As a young woman Arminta had learned to read and write, and may have had status as a house slave before becoming free.

After the war, the entire family migrated to Ripley in 1866, where the parents decided opportunities were better than in postwar Kentucky. Gabriel had earned a bonus by continuing to serve in the Army after the war and had a stake to buy land. As a youth, Charles Young attended the all-white high school in Ripley, the only one available. He graduated at age 16 at the top of his class. Following graduation, he taught school for a few years at the newly established black high school of Ripley.[1]

West Point

While teaching, Young took a competitive examination for appointment as a cadet at United States Military Academy at West Point. He achieved the second highest score in the district in 1883, and after the primary candidate dropped out, Young reported to the academy in 1884. He was not the only black student in the academy,(John Hanks Alexander entered West Point Military Academy in 1883 and graduated in 1887, Alexander and Young shared a room for three years at West Point). Young made some lifelong friends among his classmates. He had to repeat his first year because of failing mathematics. Failing an engineering class later, he passed after being personally tutored during the summer by George Washington Goethals, a brilliant engineer and assistant professor who took an interest in him. (Goethals later directed construction of the Panama Canal.) It was not unusual for candidates to require additional help in some subjects. Young's strength was in languages, and he learned several.[1]

Young graduated with his commission as a second lieutenant in 1889, the third black man to do so at the time. He was first assigned to the Tenth U.S. Cavalry Regiment. Through a reassignment, he served first with the Ninth U.S. Cavalry Regiment, serving first in Nebraska. His subsequent service of 28 years was chiefly with black troops — the Ninth U.S. Cavalry and the Tenth U.S. Cavalry, black troops nicknamed the "Buffalo Soldiers" since the Indian Wars. The armed services were racially segregated until 1948, when President Harry S. Truman integrated them by Executive order.[2]

Marriage and family

After getting established in his career, Young married Ada Mills on February 18, 1904 in Oakland, California. They had two children: Charles Noel, born in 1906 in Ohio, and Marie Aurelia, born in 1909 when Young and his family were stationed in the Philippines.[3]

Military service

Young began his service with the Ninth Cavalry in the American West: from 1889-1890 he served at Fort Robinson, Nebraska, and from 1890-1894 at Fort Duchesne, Utah.

Beginning in 1894 as a lieutenant, Young was assigned to Wilberforce College in Ohio, a historically black college (HBCU), to lead the new military sciences department, which was established under a special federal grant.[4] As a professor for four years, he was one of a number of outstanding men on the staff, including W.E.B. Du Bois, with whom he became friends.[1]

National Park assignments

In 1903, Young served as Captain of a black company at the Presidio of San Francisco. When appointed acting superintendent of Sequoia and General Grant national parks, he was the first black superintendent of a national park. At the time the military supervised the parks. Because of limited funding, the Army assigned personnel for short-term assignments during the summers, making it difficult for the officers to accomplish longer term goals, such as construction of infrastructure. Young supervised payroll accounts and directed the activities of rangers.

Young's greatest impact on the park was managing road construction, which helped to improve the underdeveloped park and enable more visitors to travel within it. Young and his troops accomplished more that summer than had teams under the three military officers who had been assigned the previous three summers. Captain Young and his troops completed a wagon road to the Giant Forest, home of the world's largest trees, and a road to the base of the famous Moro Rock. By mid-August, wagons of visitors were able to enter the mountaintop forest for the first time.[5]

With the end of the brief summer construction season, Young was transferred on November 2, 1903, and reassigned as the troop commander of the Tenth Cavalry at the Presidio. In his final report on Sequoia Park to the Secretary of the Interior, he recommended the government acquire privately held lands there, to secure more park area for future generations. This recommendation was noted in legislation to that purpose introduced in the United States House of Representatives.

Other military assignments

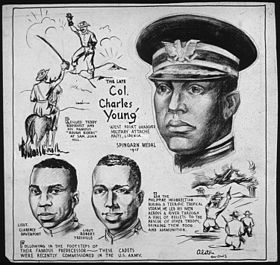

Charles Young cartoon by Charles Alston, 1943

Charles Young cartoon by Charles Alston, 1943

With the Army's founding of the Military Intelligence Department, in 1904 it assigned Young as one the first military attachés, serving in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. He was to collect intelligence on different groups in Haiti, to help identify forces that might destabilize the government. He served there for three years.

In 1908 Young was sent to the Philippines to join his Ninth Regiment and command a squadron of two troops. It was his second tour there. After his return to the US, he served for two years at Fort D.A. Russell, Wyoming.

In 1912 Young was assigned as military attaché in Liberia, the first African American to hold that post. For three years, he served as an expert adviser to the Liberian Government and also took a direct role, supervising construction of the country's infrastructure. For his achievements, in 1916 the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) awarded Young the Spingarn Medal, given annually to the African American demonstrating the highest achievement and contributions.[6]

During the 1916 Punitive Expedition by the United States into Mexico, then Major Young commanded the 2nd squadron of the 10th United States Cavalry. While leading a cavalry pistol charge against Pancho Villa's forces at Agua Caliente (1 April 1916), he routed the opposing forces without losing a single man. His swift action saved the wounded General Beltran and his men of the 13th Cavalry squadron, who had been outflanked.

Because of his exceptional leadership of the 10th Cavalry in the Mexican theater of war, Young was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel in September 1916. He was assigned as commander of Fort Huachuca, the base in Arizona of the Tenth Cavalry, nicknamed the "Buffalo Soldiers", until mid 1917.[6] He was the first African American to achieve the rank of colonel in the US Army.[7] With the outbreak of World War I, Young likely hoped for a chance to gain a promotion to general. Resistance to black officers and health problems meant he never reached this goal. He was sidelined by a diagnosis of high blood pressure, which forced him to accept a medical furlough, and was placed temporarily on the inactive list on June 22, 1917.

He returned to Wilberforce University, where he was a Professor of Military Science through most of 1918. On November 6, 1918, after Young traveled by horseback from Wilberforce, Ohio to Washington, D.C. to prove his physical fitness, he was reinstated on active duty in the Army and promoted to full Colonel.[5] In 1919, he was assigned again as military attaché to Liberia.

Young died January 8, 1922 of a kidney infection while on a reconnaissance mission in Nigeria. His body was returned to the United States, where he was given a full military funeral and buried at Arlington National Cemetery near Washington, DC. He had become a public and respected figure because of his unique achievements in the US Army, and his obituary was carried in the New York Times.[8]

Honors and legacy

- 1903 - The Visalia, California Board of Trade presented Young with a citation in appreciation of his performance as Acting Superintendent of Sequoia National Park.

- 1916 - The NAACP awarded him the Spingarn Medal for his achievements in Liberia and the US Army.

- He was elected an honorary member of the Omega Psi Phi fraternity.

- 1922 - Young's obituary appeared in the New York Times, demonstrating his national reputation

- 1922 - His funeral was one of few held at the Memorial Amphitheater at Arlington National Cemetery, where he was buried in Section 3.[8]

- Charles E. Young Elementary School, named in his honor, was built in Washington, D.C. The school is the first elementary school in Northeast D.C., and was built explicitly to improve education in the city's black neighborhoods.

- 1974 - The house where he had lived when teaching at Wilberforce University was designated a National Historic Landmark, in recognition of his historic importance.[6]

- 2001 - Senator DeWine introduced Senate Resolution 97, to recognize the contributions of the Buffalo Soldiers of the Ninth and Tenth Cavalry, and Colonel Charles D. Young.[9]

This article is based in part on a document created by the National Park Service, which is part of the U.S. government. As such, it is presumed to be in the public domain.

References

- ^ a b c d e Brian Shellum, Black Cadet in a White Bastion: Charles Young at West Point, Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska, 2006, pp. 6-13, accessed 8 Jun 2010

- ^ "Chapter 12: The President Intervenes". Center of Military History. US Army. http://www.history.army.mil/books/integration/IAF-12.htm. Retrieved 2010-04-06.

- ^ Brian G. Shellum, Black Officer in a Buffalo Soldier Regiment: The Military Career of Charles Young, Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska, 2010, p. xx, accessed 9 Jun 2010

- ^ James T. Campbell, Songs of Zion, New York: Oxford University Press, 1995, p. 262, accessed 13 Jan 2009

- ^ a b "Sequoia National Park"

- ^ a b c "Colonel Charles Young". Buffalo Soldier. Davis, Stanford L.. 2000. http://www.buffalosoldier.net/CharlesYoung.htm. Retrieved 2010-01-18.

- ^ "COL. CHARLES YOUNG DIES IN NIGERIA; Noted U.S. Cavalry Commander Was the Only Negro to Reach Rank of Colonel.". New York Times. January 13, 1922. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=9C06E4DF1531EF33A25750C1A9679C946395D6CF. Retrieved 2008-08-08.

- ^ a b "Charles D. Young", Arlington National Cemetery, accessed 9 Jun 2010

- ^ Charles Davis, "Colonel Charles Young", Buffalosoldier.net, accessed 9 Jun 2010

Additional reading

- Sweeney, W. Allison (1919), History of the American Negro in the Great World War, http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/16598 - Infobox photograph

- Chew, Abraham. A Biography of Colonel Charles Young, Washington, D.C.: R. L. Pendelton, 1923

- Greene, Robert E. Colonel Charles Young: Soldier and Diplomat, 1985

- Kilroy, David P. For Race and Country: The Life and Career of Charles Young, 2003

- Shellum, Brian G., Black Cadet in a White Bastion: Charles Young at West Point, Lincoln, NE: Bison Books, 2006.

- Shellum, Brian G., Black Officer in a Buffalo Soldier Regiment, The Military Career of Charles Young, Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2010.

- Stovall, TaRessa. The Buffalo Soldier, Philadelphia: Chelsea House Publishers, 1997

- Stewart, T. G. Buffalo Soldiers: The Colored Regulars in the United States Army, Amherst, NY: Humanity Books, 2003

External links

- "Charles Young", National Park Service

Predecessors Original units Medal of Honor recipients

(1866–1918)Edward L. Baker, Jr. · Dennis Bell · Thomas Boyne · Benjamin Brown · George Ritter Burnett · Louis H. Carpenter · John Denny · Clinton Greaves · Henry Johnson · George Jordan · Fitz Lee · Isaiah Mays · William McBryar · Thomas Shaw · Emanuel Stance · Freddie Stowers · William H. Thompkins · Augustus Walley · George H. Wanton · Moses Williams · William Othello Wilson · Brent WoodsNotable battles

(1866–1918)American Indian Wars Saline River · Texas–Indian wars · Beecher Island · Wichita I · Beaver Creek · North Fork · Red River War · Wichita II · Apache Wars · Victorio Campaign · Fort Tularosa · Bannock Uprising · Yaqui Uprising · Bear ValleySpanish–American War Philippine–American War Border War World War I See Also Categories:- Buffalo Soldiers

- 1864 births

- 1922 deaths

- African-American military personnel

- Burials at Arlington National Cemetery

- United States Army officers

- United States Military Academy alumni

- Wilberforce University

- Spingarn Medal winners

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.