- Khosrau I

-

Khosrau I Shahanshah of the Sassanian (Persian) Empire

Hunting scene showing Shah Khosrau IReign 531 CE to 579 CE (48 years) Titles Anushirvan (of the immortal soul) Died 579 CE Place of death Ctesiphon Predecessor Kavadh I Successor Hormizd IV Father Kavadh I Religious beliefs Zoroastrianism Khosrau I (also called Chosroes I in classical sources, most commonly known in Persian as Anushirvan or Anushirwan, Persian: انوشيروان meaning the immortal soul), also known as Anushiravan the Just or Anushirawan the Just (انوشیروان عادل , Anushiravān-e-ādel or انوشيروان دادگر, Anushiravān-e-dādgar) (r. 531–579), was the favourite son and successor of Kavadh I (488–531), twentieth Sassanid Emperor (Persian: Shahanshah, Great King) of Persia, and the most famous and celebrated of the Sassanid Emperors.

He laid the foundations of many cities and opulent palaces, and oversaw the repair of trade roads as well as the building of numerous bridges and dams. During Khosrau I's ambitious reign, art and science flourished in Persia and the Sassanid Empire reached its peak of glory and prosperity. His rule was preceded by his father's and succeeded by Hormizd IV. "Khosrau of the immortal soul" is one of the most popular emperors in Iranian culture and literature and, outside of Iran, his name became, like that of Caesar in the history of Rome, a designation of the Sasanian kings.[1]

Contents

Early life

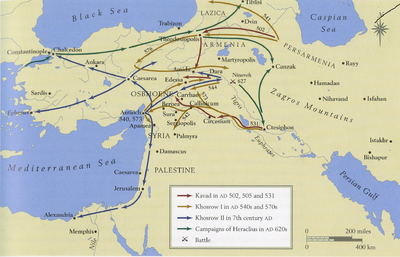

Khosrau I's father, Kavadh I, was involved with a group of Zoroastrians called the Mazdakites. The Mazdakites believed in an egalitarian society and many lower class peasants supported the Mazdakite revolution.[2] Kavadh, wanting to centralize power by taking power away from the great noble families, supported this movement. Upon Kavadh's death in 531, the Mazdakites gave their loyalty to Kavadh's eldest son, Kawus, while the noble families and the Zoroastrian Magi gave their support to Khosrau I. Khosrau presented himself as an anti-Mazdakite supporter.[3] He, much like his father, believed in a strong centralized government. Khosrau met his brother Kawus in war and defeated him as well as his Mazdakite followers. Subsequently Mazdak, as well as a majority of his followers, were executed for his heretical beliefs and Khosrau took the Sassanian throne.[4] At Khosrau's succession, Byzantine and Sassanian Persia were in open conflict with each other. Neither empire was able to get an advantage of the other, causing Emperor Justinian and King Khosrau to agree on a peace treaty in 531.[5]

Khosrau I was married to the daughter of a Turkish khaqan named in Armenian sources as Kayen[6] and in the Persian sources as Qaqim-khaqan[7]

Shahanshah

Summary

Khosrau I represents the epitome of the philosopher king in the Sassanian Empire. Upon his ascension to the throne, Khosrau did not restore power to the feudal nobility or the magi, but centralized his government.[8] Khosrau's reign is considered to be one of the most successful within the Sassanian Empire. The peace agreement between Rome and Persia in 531 gave Khosrau the chance to consolidate power and focus his attention on interior improvement.[9] His reforms and military campaigns marked a renaissance of the Sassanian Empire, which spread philosophic beliefs as well as trade goods from the far east to the far west.

Reforms

The internal reforms under Khosrau were much more important than those on the exterior frontier. The subsequent reforms resulted in the rise of a bureaucratic state at the expense of the great noble families, strengthening the central government and the power of the Shahanshah. The army too was reorganized and tied to the central government rather than local nobility allowing greater organization, faster mobilization and a far greater cavalry corps. Reforms in taxation provided the empire with stability and a much stronger economy, allowing prolonged military campaigns as well as greater revenues for the bureaucracy.[10]

Tax Reforms

Khosrau's tax reforms have been praised by several scholars, the most notable of which is F. Altheim.[11] The tax reforms, which were started under Kavadh I and completely implemented by Khosrau, strengthened the royal court by a great deal.[12] Prior to Khosrau and Kavadh's reigns, a majority of the land was owned by seven great noble families: Suren, Waraz, Karen, Aspahbadh, Spandiyadh, Mihran, and Zik.[13] These great landowners enjoyed tax exemptions from the Sassanian empire, and were tax collectors within their local provincial areas.[14]

With the outbreak of the Mazdakite revolution, there was a great uprising of peasants and lower class citizens who grabbed large portions of land under egalitarian values. As a result of this there was great confusion on land possession and ownership. Khosrau surveyed all the land within the empire indiscriminately and began to tax all land under a single program. Tax revenues that previously went to the local noble family now went to the central government treasury.[14] The fixed tax that Khosrau implemented created a more stable form of income for the treasury.

Because the tax did not vary, the treasury could estimate fairly well how much they were going to make in revenue for the year.[15] Prior to Khosrau's tax reforms, taxes were collected based on the yield that the land had produced. This system was changed to one which calculated and averaged taxation based on the water rights for each piece of property. Lands which grew date palms and olive trees used a slightly different method of taxation based on the amount of producing trees that the land contained.[14] These tax reforms of Khosrau were the stepping stone which enabled subsequent reforms in the bureaucracy and the military to take place.

Bureaucracy Reforms

The hallmark of Khosrau's bureaucratic reform was the creation of a new social class. Before, the Sassanian Empire consisted of only three social classes, magi, nobles, and peasants/commoners. Khosrau added a fourth class to this hierarchy between the nobles and the peasants, called the deghans. The deghans were small land owning citizens of the Sassanian Empire and were considered lower nobility.

Khosrau promoted honest government officials based on trust and honesty, rather than corrupt nobles and magi.[16] The small landowning deghans were favored over the high nobles because they tended to be more trustworthy and owned their loyalty to the Shah for their position in the bureaucracy.[8] The rise of deghans became the backbone of the empire because they were now held the majority of land and positions in local and provincial administration.[17]

The reduction of power of the great families helped to improve the empire. This was because previously, each great family ruled a large chunk of land and each had their own king. The name Shahanshah, meaning King of Kings, derived from the fact that there were many feudal kings in Sassanian Persia with the Shahanshah as the ruler of them all. Their fall from power meant their control was redirected to the central government and all taxes now came to the central government rather than to the local nobility.

Military Reforms

Major reforms to the military made the Persian army capable of fighting sustained wars and on multiple fronts as well deploy armies faster.[18] Prior to Khosrau's reign, much like other aspects of the empire, the military was dependent on the feudal lords of the great families to provide soldiers and cavalry. Each family would provide their own army and equipment when called by the Shahanshah. This system was replaced with the emergence of the lower deghan nobility class, who was paid and provided by the central government.[14]

The main force of the Sassanian army was the Savaran cavalry. Previously only nobles could enlist into the Savaran cavalry which was very limited and created shortages in well trained soldiers. Now that the deghan class was considered nobility, they were able to join the cavalry force and boosted the number of cavalry force significantly.[18]

The military reform focused more on organization and training of troops. The cavalry was still the most important aspect of the Persian military, with foot archers being less important, and mass peasant forces being on the bottom of the spectrum.

Khosrau discarded the old satrap system and replaced it with four military districts with a spahbad, or general, in charge of each district.[14] Before the reforms of Khusrau, the General of the Iranians (Eran-spahbed) controlled the military of the entire empire.[19] The four zones consisted of Mesopotamia in the west, the Caucasus region in the north, the Persian gulf in the central and southwest region, and Central Asia in the east. This new “quatro” system not only created a more efficient military system but also “[administration] of a vast, multiregional, multicultural, and multiracial empire.”[18]

Military

Equipment

By Khosrau's reign, super-heavy cavalrymen were discontinued and replaced with a more efficient form of cavalry. New “composite” cavalrymen were now the main cavalry force, trained to use both lances as well as bows. These versatile knights came in response of defeats from central Asian nomads. The composite cavalrymen wore spangenhelm style helmets, chain mail, and small shields. Their armor was lighter than previous Savaran cavalrymen, but they continued to carry heavy lances as well as bow case containing two bows. These composite cavalrymen proved to be much more versatile on the battlefield and were much more fluid.[20]

War With Justinian

In 532, Khosrau and Justinian, emperor of the Eastern Roman/Byzantine Empire concluded Pax Perpetuum, or the Eternal Peace in hopes of settling all land disputes between the Romans and Sassanians.[21][22] In 540, Khosrau broke the Pax Perpetuum and struck Mesopotamia and Syria. He then moved out to Antioch, taking a path that was south of the usual military route in order to extract tributes from towns along the way to Antioch.[14] The walls of Antioch had been greatly damaged during an earthquake in 525-526, and the Romans had not since repaired them because of western military campaigns, which made it much easier to conquer.[22] Khosrau sacked and burned the city at which point Justinian sued for peace, giving Khosrau a large amount of money. While traveling back to Persia, Khosrau took ransoms from multiple Byzantine towns at which point Justinian called off his truce and prepared to send his great commander Belisarius to move against the Sassanians.[14]

There were many motives behind Khosrau's strike against the Byzantines during their Eternal Peace. Emissaries from the Ostrogoth kingdom in the west appealed to Khosrau to put pressure on the eastern front of East Rome.[14] Gothic envoys spoke to Khosrau's court and spoke of Justinian's goal to unite the world under Roman rule. The Gothic envoys persuasively informed Khosrau that if Persia did not act soon, they would soon become victims of Byzantine aggression.[23] It was the Persian military's fear that once the Roman army had conquered the west, they would turn east and strike down Persia. In order to prevent this, Khosrau preemptively struck Antioch.[24] There were also pressure and unrest in both Arabia and Armenian who were both eager for war.[14]

A year after his sack of Antioch, Khosrau brought his army north to Lazica on request of the Lazic King to fend off Byzantine raids into his territory. At the same time, Belisarius arrived in Mesopotamia and began attacking the city of Nisbis. Although Belisarius had greatly outnumbered the city garrison, the city was too well fortified and he was forced to ravage the country around the Nisbis subsequently getting recalled back west.[14]

After successful campaigns in Armenia, Khosrau was encouraged once again to attack Syria. Khosrau turned south towards Edessa and besieged the city. Edessa was now a much more important city than Antioch was, but the garrison which occupied the city was able to resist the siege. The Persians were forced to retreat from Edessa, but were able to forge a five year truce with the Byzantine Empire. Four years into the five year truce, rebellion against Sassanian control broke out in Lazica. In response, a Byzantine army was sent to support the people of Lazica, effectively ending the established truce and thus continuing the Lazic Wars.[14]

Lazic Wars

The Lazic wars are intertwined with Khosrau's war with Justinian insomuch as there were many battles which overlapped each other, yet they are generally considered different wars. Whereas Khosrau's wars with Justinian were fought at the sake of fighting Romans, the Lazic wars were often fought on behalf of Lazic and Armenian citizens, or in defense of Sassanian outposts in Lazica.

The Caucasus region, especially northern Armenia, has always been a major area of Romano-Sassanian rivalry.[25] The Lazic wars began when the Sassanians intervened on Byzantine encroachments on behalf of the King of Lazica. Khosrau was able to penetrate deep into Lazica and secure the fortress city of Petra, located on the coast of the Black Sea, which provided Persia with a strategic port.[14]

Khosrau was forced to pull out of Lazica, leaving only a 1,500 man garrison in Petra to defend the territory while he went to deal with Belisarius in Mesopotamia.[26] In 542, Justinian attempted to make a truce with Khosrau, but rather than sending peace delegates, Justinian sent a massive 30,000 man army into Armenia. Sassanian general Nabed's army of 4,000 was severely outnumbered and was forced to retreat to the town of Anglon in Armenia.[26] The Byzantine army pursued the Sassanians into the town but to Byzantines' dismay, they walked into an ambush and were completely routed. This massive defeat in 543 gave Sassanians the offensive in the Lazic war as well as in the war against Justinian.[21]

Justinian and Khosrau declared a five year truce in 545 but war continued to ravage the Caucasus region. An uprising of anti-Sassanian control struck the Lazica region in 547. In response, Justinian sent 8,000 troops in support of Lazic King Gubazes.[26] A Byzantine-Lazic army besieged the city of Petra, holding a garrison of 1,500 Sassanian troops. As a result, 1,200 of the Sassanian soldiers were killed, but the Byzantine-Lazic coalition was soon forced to retreat when a relief army of 30,000 pro-Sassanian troop arrived.[26]

In 549 the previous truce between Justinian and Khosrau was disregarded and full war broke out once again between Persians and Romans. The last major decisive battle of the Lazic wars came in 556 when Byzantine general Martin defeated a massive Sassanian force led by a Persian nakhvaegan (field marshal).[27] Negotiations between Khosrau and Justinian opened in 556, leading to the establishment of a 51 year peace agreement in 561 in which Persians would leave Lazica in return for an annual payment of gold.[14]

According to ancient historian Meander Protector, a minor official in Justinian's court, there were 12 points to the treaty, stated in the following passage:

“ 1. Through the pass at the place called Tzon and through the Caspian Gates the Persians shall not allow the Huns or Alans or other barbarians access to the Roman Empire, nor shall the Romans either in that area or on any other part of the Persian frontier send an army against the Persians.

2. The Saracen allies of both states shall themselves also abide by these agreements and those of the Persians shall not attack the Romans, nor those of the Romans the Persians.

3. Roman and Persian merchants of all kinds of goods, as well as similar tradesmen, shall conduct their business according to the established practice through the specified customs posts.

4. Ambassadors and all others using the public post to deliver messages, both those traveling to Roman and those to Persian territory, shall be honoured each according to his status and rank and shall receive the appropriate attention. They shall be sent back without delay, but shall be able to exchange the trade goods which they have brought without hindrance or any impost.

5. It is agreed that Saracen and all other barbarian merchants of either state shall not travel by strange roads but shall go by Nisibis and Daras, and shall not cross into foreign territory without official permission. But if they dare anything contrary to the agreement (that is to say, if they engage in tax-dodging, so-called), they shall be hunted down by the officers of the frontier and handed over for punishment together with the merchandise which they are carrying, whether Assyrian or Roman.

6. If anyone during the period of hostilities defected either from the Romans to the Persians or from the Persians to the Romans and if he should give himself up and wish to return to his home, he shall not be prevented from so doing and no obstacle shall be put in his way. But those who in time of peace defect and desert from one side to the other shall not be received, but every means shall be used to return them, even against their will, to those from whom they fled.

7. Those who complain that they have suffered some hurt at the hands of subjects of the other state shall settle the dispute equitably, meeting at the border either in person or through their own representatives before the officials of both states, and in this manner the guilty party shall make good the damage.

8. Henceforth, the Persians shall not complain to the Romans about the fortification of Daras. But in future neither state shall fortify or protect with a wall any place along the frontier, so that no occasion for dispute shall arise from such an act and the treaty be broken.

9. The forces of one state shall not attack or make war upon a people or any other territory subject to the other, but without inflicting or suffering injury shall remain where they are so that they too might enjoy the peace.

10. A large force, beyond what is adequate to defend the town, shall not be stationed at Daras, and the general of the East shall not have his headquarters there, in order that this not lead to incursions against or injury to the Persians. It was agreed that if some such should happen, the commander at Daras should deal with the offence.

11. If a city causes damage to or destroys the property of a city of the other side not in legitimate hostilities and with a regular military force but by guile and theft (for there are such godless men who do these things to provide a pretext for war), it was agreed that the judges stationed on the frontiers of both states should make a thorough investigation of such acts and punish them. If these prove unable to check the damage that neighbours are inflicting on each other, it was agreed that the case should be referred to the general of the East on the understanding that if the dispute were not settled within six months and the plaintiff had not recovered his losses, the offender should be liable to the plaintiff for a double indemnity. It was agreed that if the matter were not settled in this way, the injured party should send a deputation to the sovereign of the offender. If within one year the sovereign does not give satisfaction and the plaintiff does not receive the double indemnity due to him, the treaty shall be regarded as broken in respect of this clause.

12. Here you might find prayers to God and imprecations to the effect that may God be gracious and ever an ally to him who abides by the peace, but if anyone with deceit wishes to alter any of the agreements, may God be his adversary and enemy.

13. The treaty is for fifty years, and the terms of the peace shall be in force for fifty years, the year being reckoned according to the old fashion as ending with the threehundred- and-sixty-fifth day.[28]

” War in the East

With a stable peace agreement with the Byzantines in the west, Khosrau was now able to focus his attention on the eastern Hephthalites.[29] Even with the growth of Persian military power under Khosrau's reforms, the Sassanians were still uneasy at the prospect of attacking the Hephthalite on their own and began to seek allies.[29] Their answer came in the form of Turkic incursions into Central Asia.[21] The movement of Turkic people into Central Asia very quickly made them natural enemies and competitors to the Hephthalites.[29]

The Hephthalites were a strong military power but they lacked the organization to fight on multiple fronts.[29] The Persians and the Turkic tribes made an alliance and launched a two pronged attack on the Hephthalites, taking advantage of their disorganization and disunity. As a result, the Turkic tribes took the territory north of the Oxus river, while the Persians annexed land to the south.[14]

Friendly relations between Turks and Persians quickly deteriorated after the conquest of Hephthalite peoples. Both Turks and Persians wanted to dominate the Silk Road and the trade industry between the west and the far east.[14] In 568 a Turkish embassy was sent to Byzantine to propose an alliance and two pronged attack on the Sassanian Empire. Fortunately for the Persians, nothing ever came from this proposal.[30]

Campaign in Yemen Against Ethiopia

In 522, before Khosrau's reign, a group of monophysite Ethiopians led an attack on the dominant Himyarites of southern Arabia. The local Arab leader was able to resist the attack, and appealed to the Sassanians for aid, while the Ethiopians subsequently turned towards the Byzantines for help. The Ethiopians sent another force across the Red Sea and this time successfully killed the Arab leader and replaced him with an Ethiopian man to be king of the region.[14]

In 531, Justinian suggested that the Ethiopians of Yemen should cut out the Persians from Indian trade by maritime trade with the Indians. The Ethiopians never met this request because an Ethiopian general named Abraha took control of the Yemenite throne and created an independent nation.[14] After Abraha's death one of his sons, Ma'd-Karib, went into exile while his half-brother took the throne. After being denied by Justinian, Ma'd-Karib sought help from Khosrau, who sent a small fleet and army under commander Vahriz to depose the current king of Yemen. After capturing the capital city San'a'l, Ma'd-Karib's son, Saif, was put on the throne.[14]

Justinian was ultimately responsible for Sassanian maritime presence in Yemen. By not providing the Yemenite Arabs support, Khosrau was able to help Ma'd-Karib and subsequently established Yemen as a principality of the Sassanian Empire.[31]

War With Justin II

Justinian died in 565 and left Justin II to succeed the throne. In 555, The Sassanian governor of Armenia built a fire temple at Dvin and put to death a popular and influential member of the Mamikonian noble family. This execution created tremendous civil unrest and led to a revolt and massacre of the Governor and his personal guard in 571. Justin II took advantage of this revolt and used it as an excuse to stop paying annual payments to Khosrau, effectively putting an end to the 51 year peace treaty that was established ten years earlier. The Armenians were considered allies to the Byzantine Empire and a Byzantine army was sent into Sassanian territory and besieged Nisbis in 572.[14]

Justin was succeeded by Tiberius, a high ranking military officer in 578.[32] Khosrau invaded Armenia once again feeling that he had the upper hand, and was initially successful. Soon after, the tables turned and the Byzantines gained a lot of local support. Another truce was attempted to be made in 578, but was abandoned when the Sassanian's gained a great victory. The war turned again when Byzantine commander Maurice entered the field and captured many Sassanian settlements.[14] The revolt came to an end when Khosrau gave amnesty to Armenia and brought them back into the Sassanian empire. Peace negotiations were once again brought back up, but abruptly ended with the death of Khosrau in 579.[33]

Building Projects

Khosrau's reign marked an expansion in building. Khosrau constructed a number of walls on his frontiers to protect from nomadic incursions as well as other enemies. On the southeast frontier he built a wall called the Wall of the Arabs in order to prevent Arab nomads from raiding his empire. In the northeast he built a wall to protect the interior of his empire from the Hephthalite and Turkish threat that was growing on his boarder.[21] His wall building campaign was also extended into the Caucasus region where he built massive walls at Derbent.[34]

After the conquest of Antioch in 541, Khosrau built a new city near Ctesiphon for the inhabitants he captured. He called this new city Weh Antiok Khusrau or literally, “better than Antioch Khosrau built this.”[35] Local inhabitants of the area called the new city Rumagan, meaning “town of the Greeks” and Arabs called the city al-Rumiyya. Along with Weh Antiok, Khosrau built a number of fortified cities.[17]

Khosrau I greatly improved the road system within the Sassanian empire. These roads greatly improved the quickness that the armies were able to move, increasing the efficiency of the military. This led to greater defense of the empire as well as much quicker transportation of military intelligence. Chains of stations were also built along the roads. This allowed couriers to travel much more quickly and have safe resting stops as well as provide travelers with shelter.[14]

Philosopher King

Khosrau I was known to be a great patron of philosophy and knowledge. An entry in the Chronicle of Séert reads:

Khosrau was very learned in philosophy, which he had studied, it is said, under Mar Bar Samma, bishop of Qardu, and under Paul the Persian Philosopher.[36]Khosrau I accepted refugees coming from the Eastern Roman Empire when Justinian closed the neo-Platonist schools in Athens in 529.[21] He was greatly interested in Indian philosophy, science, math, and medicine. He sent multiple embassies and gifts to the Indian court and requested them to send back philosophers to teach in his court in return.[37] Khosrau made many translations of texts from Greek, Sanskrit, and Syriac into Middle Persian.[14] He received the title of “Plato's Philosopher King” by the Greek refugees that he allowed into his empire because of his great interest in Platonic philosophy.[21]

A synthesis of Greek, Persian, Indian, and Armenian learning traditions took place within the Sassanian Empire. One outcome of this synthesis created what is known as bimaristan, the first hospital that introduced a concept of segregating wards according to pathology. Greek pharmacology fused with Iranian and Indian traditions resulted in significant advances in medicine.[37] According to historian Richard Frye, this great influx of knowledge created a renaissance during, and proceeding Khosrau's reign.[38]

Intellectual games such as chess and backgammon demonstrated and celebrated the diplomatic relationship between Khosrau and a “great king of India.” The vizier of the Indian king invented chess as a cheerful, playful challenge to King Khosrau. When the game was sent to Iran it came with a letter which read: “As your name is the King of Kings, all your emperorship over us connotes that your wise men should be wiser than ours. Either you send us an explanation of this game of chess or send revenue and tribute us.”[39] Khosrau's grand vizier successfully solved the riddle and figured out how to play chess. In response the wise vizier created the game backgammon and sent it to the Indian court with the same message. The King was not able to solve the riddle and was forced to pay tribute.[39]

Academy of Gondishapur

Khosrau I is known to have either founded or greatly expanded the Academy of Gondishapur, located in the city of Gundeshapur.[40] As to the development of non-religious knowledge and research in Persia and apart from historical evidence given on such traditions in the preceding Persian Empires, there are reports on systematic activities initiated by the Sasanian court as early as in the first decades of Sasanian rule. The Middle Persian encyclopaedia Denkard states that during the reign of Shapur I writings of this kind were collected and added to the Avesta. And an atmosphere of vivid reflection and discussion at the early Sasanian court in the third century AD is reflected in such accounts.[41] The foundation of the Academy of Gondishapur introduced the studies of philosophy, medicine, physics, poetry, rhetoric, and astronomy into the Sasanian court.[42] According to some historical accounts, this famous learning center was built in order to provide a place for incoming Greek refugees to study and share their knowledge.[37] Gundeshapur became the focal point of the combination of Greek and Indian sciences along with Persian and Aramaic traditions. The cosmopolitan which was introduced by the institution of Gondishapur became a catalyst for modern studies.

Legacy

Although Khosrau's achievements were highly successful and helped centralize the empire, they did not last long after his death. The local officials and great noble families resented the fact that their power had been stripped away from them and began to regain power quickly after his death.[14] Khosrau's reign had a major impact on Islamic culture and political life. Many of his policies and reforms where brought into the Islamic nation in their transformation from a decentralized oligarchical into an imperial empire.[14]

There are a considerable amount of Islamic work that was inspired by the reign of Khosrau I, for example the Kitab al-Taj of Jahiz.[17] There are a considerable amount of Islamic texts that refer to Khosrau's reign that it is sometimes hard to tell what is fact and what is fallacy.[14]

His reign signifies the promotion and possibly even the creation of the Silk Road between ancient China, India, and the western world.[37] Richard Frye makes the argument that Khosrau's rationale behind his numerous wars with the Byzantine empire as well as the eastern Hephthalites was to establish the Sassanian dominance on this trade route.[14]

Khosrau IPreceded by

Kavadh IGreat King (Shah) of Persia

531–579Succeeded by

Hormizd IVReferences

- Addai Scher, ed., Histoire Nestorienne (Chronique de Séert), Patrologia Orientalis 7. 1910.

- Frye, Richard N. The Heritage of Persia. The World Publishing Company, 1963.

- Frye, Richard N. The Heritage of Persia. Costa Mesa: Mazda Publishers, 1993. 240-269.

- Howard-Johnston, James. “State and Society in Late Antique Iran,” in The Sassanian Era. Edited by Vesta Sarkhosh Curtis and Sarah Stewart. London: I.B. Tauris & Co 2008, 118-129.

- Dignas, Beate and Winter, Engelbert. Rome and Persia in Late Antiquity : Neighbours and Rivals. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2007

- Canepa, Matthew P. The Twos Eyes of Earth. Berkley: University of California 2009.

- Daryaee, Touraj. Sasanian Persia: The Rise and Fall of an Empire. London: I.B. Tauris & Co. 2009.

- Farrokh, Dr. Kaveh. Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War. Oxford: Osprey Publishing 2007.

- Frye, Richard R. “THE REFORMS OF CHOSROES ANUSHIRVAN ('OF THE IMMORTAL SOUL').” The History of Ancient Iran. http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/med/fryehst.html

- Taylor, Gail Marlow. “The Physicians of Jundishapur.” e-Sasanika. 2010. http://www.humanities.uci.edu/sasanika/pdf/e-sasanika11-Taylor.pdf

- Meander Protector. Fragments 6.1-6.3. Translated by R.C. Blockey, edited by Khodadad Rezakhani. http://www.humanities.uci.edu/sasanika/pdf/Menander6-1.pdf

External links

- Khosrau In Iran Science Island(In Persian)

- The Reforms of Khosrow Anushirvan

- Meander Protector Fragments 6.1-6.3

- The Physicians of Jundishapur

Notes

- ^ Frye, Richard. The Heritage of Persia. The World Publishing Company, 1963, p. 215

- ^ Frye, Richard. The Heritage of Persia. Mazda Publishers, 1993, p. 251

- ^ Daryaee, Touraj. Sassanian Persia: The Rise and Fall of an Empire. I.B. Tauris & Co., 2009, p. 28

- ^ Daryaee 2009, p. 28-29

- ^ Dingas, Beate, and Winter, Engelbert. Rome and Persia in Late Antiquity. Cambridge University Press, 2007, 38

- ^ Ter-Mkrticnyan L.H. Armyanskiye istochniki - Sredney Azii V - VII vv., p. 57.

- ^ The Farsnama of Ibnu'l-Balkhi, pp. 24, 94.

- ^ a b Daryaee 2009, p. 29

- ^ Dingas, Winter 2007, 28

- ^ Frye 1993, 258, 260

- ^ Frye 1993, 257

- ^ Frye, Richard. “The History of Ancient Iran.” Internet Islamic History Sourcebook. http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/med/fryehst.html

- ^ Johntson-Howard, James. “State and Society in Late Antiquity Iran,” in The Sassanian Era. Edited by Vesta Sarkhosh Curtis and Sarah Stewart. I.B. Tauris & Co., 2008, 126

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Frye Ancient Iran

- ^ Frye 1993, 258

- ^ Farrokh, Dr. Kaveh. Shadows in the Desert. Osprey Publishing, 2007, p. 230-230

- ^ a b c Frye 1993, 259

- ^ a b c Farrokh 2007, 229

- ^ Daryaee 2009, 124

- ^ Farrokh 2007, 231

- ^ a b c d e f Daryaee 2009, p. 30

- ^ a b Farrokh 2007, 230

- ^ Dingas, Beate, and Winter, Engelbert. Rome and Persia in Late Antiquity. Cambridge University Press, 2007, 107

- ^ Farrokh 2007, 233

- ^ Farrokh 2007, 234

- ^ a b c d Farrokh 2007, 235

- ^ Farrokh 2007, 236

- ^ Meander Protector. Fragments 6.1-6.3. Translated by R.C. Blockey, edited by Khodadad Rezakhani. http://www.humanities.uci.edu/sasanika/pdf/Menander6-1.pdf

- ^ a b c d Farrokh 2007, 238

- ^ Dingas, Winter 2007, 115

- ^ Farrokh 2007, 237

- ^ Farrokh 2007, 240

- ^ Farrokh 2007, 240-241

- ^ Frye 1993, 260

- ^ Dingas, Winter 2007, 109

- ^ Addai Scher, ed., Histoire Nestorienne (Chronique de Seért), Patrologia Orientalis 7 (1910), 147.

- ^ a b c d Farrokh 2007, 241

- ^ Frye 1993, 261

- ^ a b Canepa 2009, p. 181

- ^ Taylor, Gail Marlow. “The Physicians of Jundishapur.” e-Sasanika. 2010. http://www.humanities.uci.edu/sasanika/pdf/e-sasanika11-Taylor.pdf

- ^ Daryaee, Touraj. Sasanian Persia: The Rise and Fall of an Empire. I.B. Tauris & Co., 2009, p. 83.

- ^ Taylor 2010 Jundishapur

Ardashir I (224–241) · Shapur I (241–272) · Hormizd I (272–273) · Bahram I (273–276) · Bahram II (276–293) · Bahram III (293) · Narseh (293–302) · Hormizd II (302–309) · Adhur Narseh (309) · Shapur II (309–379) · Ardashir II (379–383) · Shapur III (383–388) · Bahram IV (388–399) · Yazdegerd I (399–420) · Bahram V (420–438) · Yazdegerd II (438–457) · Hormizd III§ (457–459) · Peroz I (457–484) · Balash (484–488) · Kavadh I (488–496) · Djamasp (496–498) · Kavadh I (498–531) · Khosrau I (531–579) · Hormizd IV (579–590) · Bahram VI Chobin§ (590–591) · Khosrau II (591–628) · Bistam (Sassanid king)§ (591–595) · Hormizd V§ (593) · Kavadh II (628) · Ardashir III (628–630) · Shahrbaraz§ (630) · Khosrau III§ (630) · Borandukht (630–631) · Azarmidokht (631) · Hormizd VI (631–632) · Khosrau IV (631–633) · Yazdegerd III (632–651) · Peroz II (pretender)§ usurpers or rival claimants

Categories:- 501 births

- 579 deaths

- Persian history

- Sassanid dynasty

- 6th-century monarchs in the Middle East

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.