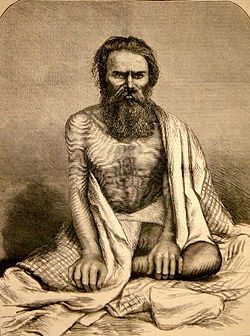

- Nana Sahib

-

For Peshwa Balaji Bajirao of Pune, see Nanasaheb Peshwa.

Nana Saheb

Born 1820

BithoorDied --

--Nationality Indian Title Peshwa Predecessor Baji Rao II Successor none Children Shamsher Bahaduar (went to Nepal) Parents Narayan Bhatt and Ganga Bai Nana Sahib (born 1824), born as Dhondu Pant(Marathi- धोंडू पंत ), was an Indian leader during the Rebellion of 1857. As the adopted son of the exiled Maratha Peshwa Baji Rao II, he sought to restore the Maratha confederacy and the Peshwa tradition.

Contents

Early life

Nana Sahib was born as Dhondu Pant to Narayan Bhatt and Ganga Bai. In 1827, he was adopted by the Maratha Peshwa Baji Rao II. The East India Company exiled Baji Rao II to Bithoor near Cawnpore (now Kanpur), where Nana Sahib was brought up.

Nana Sahib's close associates included Tantya Tope and Azimullah Khan; Tatya Tope was the son of Pandurang Rao Tope, an important noble at the court of the Peshwa Baji Rao II. After Baji Rao was exiled to Bithoor, Pandurang Rao and his family also shifted t

Pension

Through his adoption, Nana Sahib was heir-presumptive to the throne, and was eligible for an annual pension of £80,000 from the East India Company. However, after the death of Baji Rao II, the Company stopped the pension on the grounds that Nana Sahib was not a natural born heir. Nana Sahib was highly offended, and sent his envoy (Azimullah Khan) to England in 1853 to plead his case with the British Government. However, Azimullah Khan was unable to convince the British to resume the pension, and returned to India in 1855.

Role in the War of Independence of 1857

Main article: Siege of Cawnpore[1] He won the confidence of Charles Hillersdon, the collector of Cawnpore. It was planned that Nana Sahib would assemble a force of 1,500 soldiers, in case the rebellion spread to Cawnpore.[2]

On June 5, 1857, at the time of rebellion by forces of the East India Company at Cawnpore, the British contingent had taken refuge at an entrenchment in the southern part of the town. Amid the prevailing chaos in Cawnpore, Nana Sahib and his forces entered the British magazine situated in the northern part of the town. The soldiers of the 53rd Native Infantry, which was guarding the magazine, thought that Nana Sahib had come to guard the magazine on behalf of the British. However, once he entered the magazine, Nana Sahib announced that he was a participant in the rebellion against the British, and intended to be a vassal of Bahadur Shah II.[3]

After taking possession of the Company treasury, Nana Sahib advanced up the Grand Trunk Road. He wanted to restore the Maratha confederacy under the Peshwa tradition, and decided to capture Cawnpore. On his way, Nana Sahib met the rebel Company soldiers at Kalyanpur. The soldiers were on their way to Delhi, to meet Bahadur Shah II. Nana Sahib wanted them to go back to Kanpur, and help him in defeating the British. The soldiers were reluctant at first, but decided to join Nana Sahib, when he promised to double their pay and reward them with gold, if they were to destroy the British entrenchment.

Attack on Wheeler's entrenchment

On June 5, 1857, Nana Sahib sent a letter to General Wheeler informing him to expect an attack next morning at 10 AM. On June 6, Nana Sahib's forces (including the rebel soldiers) attacked the British entrenchment at 10:30 AM. The British were not adequately prepared for the attack but managed to defend themselves as the attacking forces were reluctant to enter the entrenchment. Nana Sahib's forces had been led to falsely believe that the entrenchment had gunpowder-filled trenches that would explode if they got closer.[3] The British held out in their makeshift fort for three weeks with little water and food supplies, and lost many lives due to sunstroke and lack of water.

As the news of Nana Sahib's advances over the British garrison spread, several of the rebel sepoys joined him. By June 10, he was believed to be leading around twelve thousand to fifteen thousand Indian soldiers.[4] During the first week of the siege, Nana Sahib's forces encircled the attachment, created loopholes and established firing positions from the surrounding buildings. The British Captain John Moore retaliated and launched night-time sorties. Nana Sahib retreated his headquarter to Savada House (or Savada Kothi), which was situated around two miles away. In response to Moore's sorties, Nana Sahib decided to attempt a direct assault on the British entrenchment, but the rebel soldiers displayed a lack of enthusiasm.[3]

The sniper fire and the bombardment continued until June 23, 1857, the 100th anniversary of the Battle of Plassey. The Battle of Plassey, which took place on June 23, 1757, was one of the pivotal battles leading to the expansion of the British rule in India. One of the driving forces of the rebellion by sepoys, was a prophecy that predicted the downfall of East India Company rule in India exactly one hundred years after the Battle of Plassey.[5] This prompted the rebel soldiers under Nana Sahib to launch a major attack on the British entrenchment on June 23, 1857. However, they were unable to gain an entry into the entrenchment by the end of the day.

The British camp had been steadily losing its soldiers to successive bombardments, sniper fire, and assaults by Nana Sahib's forces. It was also suffering from disease and low supplies of food, water and medicine. General Wheeler's personal morale had been low, after his son Lieutenant Gordon Wheeler was decapitated in an assault on the barracks.[3] At the same time, Nana Sahib's forces were wary of entering the entrenchment, as they believed that it had gunpowder-filled trenches.

Nana Sahib and his advisers came up with a plan to end the deadlock. On June 24, Nana Sahib sent a female European prisoner, Rose Greenway, to the entrenchment to convey their message. In return for a surrender, he promised the safe passage of the British to the Satichaura Ghat, a dock on the Ganges from which they could depart for Allahabad.[4] General Wheeler rejected the offer, because it had not been signed, and there was no guarantee that the offer was made by Nana Sahib himself.

Next day, on June 25, Nana Sahib sent a second note, signed by himself, through another female prisoner, Mrs. Jacobi. The British camp divided into two groups with different opinions — one group was in favor of continuing the defence, while the second group was willing to trust Nana Sahib. During the next 24 hours, there was no bombardment from Nana Sahib's forces. Finally, General Wheeler decided to surrender, in return for a safe passage to Allahabad. After a day of preparation and burying their dead, the British decided to leave for Allahabad on the morning of June 27, 1857.

Satichaura Ghat massacre

On the morning of the June 27 a large British column led by General Wheeler emerged out of the entrenchment. Nana Sahib sent a number of carts, dolis and elephants to enable the women, the children and the sick to proceed to the river banks. The British officers and military men were allowed to take their arms and ammunition with them, and were escorted by nearly the whole of the rebel army.[4] The British reached the Satichaura Ghat (now Satti Chaura Ghat) by 8 AM. Nana Sahib had arranged around 40 boats, belonging to a boatman called Hardev Mallah, for their departure to Allahabad.[6]

The Ganges river was unusually dry at the Satichaura Ghat, and the British found it difficult to drift the boats away. General Wheeler and his party were the first aboard and the first to manage to set their boat adrift. There was some confusion, as the Indian boatmen jumped overboard and started swimming toward the banks. During their jump, some of the cooking fires were knocked off, setting some of the boats ablaze. Though controversy surrounds what exactly happened next at the Satichaura Ghat,[4] and it is unknown who fired the first shot,[6] it is known that soon afterwards, the departing British were attacked by the rebel sepoys, and were either killed or captured.

Some of the British officers later claimed that Nana Sahib had placed the boats as high in the mud as possible, on purpose to cause delay. They also claim that Nana Sahib had previously arranged for the rebels to fire upon and kill all the English. Although the East India Company later accused Nana Sahib of betrayal and murder of innocent people, no definitive evidence has ever been found to prove that Nana Sahib had pre-planned or ordered the massacre.[7] Some historians believe that the Satichaura Ghat massacre was the result of confusion, and not of any plan implemented by Nana Sahib and his associates.[8]

Nevertheless, the fact that sniper fire from cannons pre-positioned along the riverbank was reported on the scene might suggest pre-planning. Whatever the case, amid the prevailing confusion at the Satichaura Ghat, Nana Sahib's general Tantya Tope allegedly ordered the 2nd Bengal Cavalry unit and some artillery units to open fire on the British.[3] The rebel cavalry sowars moved into the water to kill the remaining British soldiers with swords and pistols. The surviving men were killed, while women and children were captured, as Nana Sahib did not approve of their killing.[9] Around 120 women and children were taken prisoner and escorted to Savada House, Nana Sahib's headquarters during the siege.

The rebel soldiers also pursued General Wheeler's boat, which was slowly drifting to safer waters. After some firing, the British men on the boat decided to fly the white flag. They were escorted off the boat and taken back to Savada house. The surviving British men were seated on the ground, as Nana Sahib's soldiers got ready to kill them. The women insisted that they would die with their husbands, but were pulled away. Nana Sahib granted the British chaplain Moncrieff's request to read prayers before they died.[10] The British were initially wounded with the guns, and then killed with the swords.[4] The women and children were taken to Savada House to be reunited with their remaining colleagues.

Bibighar massacre

The surviving British women and children, around 120 in number, were moved from the Savada House to Bibighar ("the House of the Ladies"), a villa-type house in Cawnpore. They were later joined by some other women and children, the survivors from General Wheeler's boat. Another group of British women and children from Fatehgarh, and some other captive European women were also confined to Bibighar. In total, there were around 200 women and children in Bibighar.[11]

Nana Sahib placed the care for these survivors under a prostitute called Hussaini Khanum (also known as Hussaini Begum). He decided to use these prisoners for bargaining with the East India Company.[3] The Company forces consisting of around 1000 British, 150 Sikh soldiers and 30 irregular cavalry had set out from Allahabad, under the command of General Henry Havelock, to retake Cawnpore and Lucknow.[10] Havelock's forces were later joined by the forces under the command of Major Renaud and James Neill. Nana Sahib demanded that the East India Company forces under General Havelock and Neill retreat to Allahabad. However, the Company forces advanced relentlessly towards Cawnpore. Nana Sahib sent an army to check their advance. The two armies met at Fatehpur on July 12, where General Havelock's forces emerged victorious and captured the town.

Nana Sahib then sent another force under the command of his brother, Bala Rao. On July 15, the British forces under General Havelock defeated Bala Rao's army in the Battle of Aong, just outside the Aong village.[3] On July 16, General Havelock's forces started advancing to Cawnpore. During the Battle of Aong, Havelock was able to capture some of the rebel soldiers, who informed him that there was an army of 5,000 rebel soldiers with 8 artillery pieces further up the road. Havelock decided to launch a flank attack on this army, but the rebel soldiers spotted the flanking maneuver and opened fire. The battle resulted in heavy casualties on both sides, but cleared the road to Cawnpore for the British.

By this time, it became clear that the Company forces were approaching Cawnpore, and Nana Sahib's bargaining attempts had failed. Nana Sahib was informed that the British troops led by Havelock and Neill were indulging in violence against the Indian villagers.[12] Some believe that the Bibighar massacre was a reaction to the news of violence being perpetrated by the advancing British troops.[8]

Nana Sahib, and his associates, including Tantya Tope and Azimullah Khan, debated about what to do with the captives at Bibighar. Some of Nana Sahib's advisors had already decided to kill the captives at Bibighar, as revenge for the murders of Indians by the advancing British forces.[12] The women of Nana Sahib's household opposed the decision and went on a hunger strike, but their efforts went in vain.[12]

Finally, on July 15, an order was given to kill the women and children imprisoned at Bibighar. Although some Company historians stated that the order for the massacre was given by Nana Sahib,[10] the details of the incident, such as who ordered the massacre, are not clear.[11][13] According to some sources, Azimullah Khan ordered the killings of women and children at Bibighar.[14]

At first, the rebel sepoys refused to obey the order to kill women and children. When they were threatened with execution for dereliction of duty some of them agreed to remove the women and children from the courtyard. Nana Sahib left the building because he didn't want to be a witness to the enfolding massacre.[3]

The British women and children were ordered to come out of the assembly rooms, but they refused to do so. The rebel soldiers then started firing through the holes in the boarded windows. After the first round of firing, the soldiers were disturbed by the cries of the captives, and adamantly refused to fire at the women and children.

An angry Begum Hussaini Khanum termed the sepoys' act as cowardice, and asked her lover Sarvur Khan to finish the job of killing the captives.[3] Sarvur Khan hired some butchers, who murdered the surviving women and children with cleavers. The butchers left, when it seemed that all the captives had been killed. However, a few women and children had managed to survive by hiding under the other dead bodies. It was agreed that the bodies of the victims would be thrown down a dry well by some sweepers. The next morning, when the rebels arrived to dispose off the bodies, they found that three women and three children aged between four and seven years old were still alive.[12] The surviving women were cast into the well by the sweepers who had also been told to strip the bodies of the murder victims. The sweepers then threw the three little boys into the well one at a time, the youngest first. Some victims, among them small children, were therefore buried alive in a heap of dead corpses.[4]

Recapture of Cawnpore by the British

The Company forces reached Cawnpore on July 16, 1857. General Havelock was informed that Nana Sahib had taken up a position at the Ahirwa village. His forces launched an attack on Nana Sahib's forces, and emerged victorious. Nana Sahib then blew up the Cawnpore magazine, abandoned the place, and retreated to Bithoor. When the British soldiers came to know about the Bibighar massacre, they indulged in retaliatory violence, including looting and burning of houses.[3][15] On July 19, General Havelock resumed operations at Bithoor, but Nana Sahib had already escaped. Nana Sahib's palace at Bithoor was occupied without resistance. The British troops seized guns, elephants and camels, and set Nana Sahib's palace to fire.

Disappearance

Nana Sahib disappeared after the British recapture of Cawnpore. His general, Tantya Tope, tried to recapture Cawnpore in November 1857, after gathering a large army, mainly consisting of the rebel soldiers from the Gwalior contingent. He managed to take control of all the routes west and north-west of Cawnpore, but was later defeated in the Second Battle of Cawnpore.

In September 1857, Nana Sahib was reported to have fallen to malarious fever; however, this is doubtful.[16] Rani Laxmibai, Tatya Tope and Rao Saheb (Nana Sahib's close confidante) proclaimed Nana Sahib as their Peshwa in June 1858 at Gwalior. By 1859, Nana Sahib was reported to have fled to Nepal. In February 1860, the British were informed that Nana Sahib's wives had taken refuge in Nepal, where they resided in a house close to Thapathali. Nana Sahib himself was reported to be living in the interior of Nepal.[17]

Nana Sahib's ultimate fate was never known. Up until 1888 there were rumours and reports that he had been captured and a number of individuals turned themselves in to the British claiming to be the aged Nana. As these reports turned out to be untrue further attempts at apprehending him were abandoned. There were also reports of him being spotted in Constantinople.

Jules Verne's novel The End of Nana Sahib (also published under the name "The Steam House"), taking place in India ten years after the 1857 events, is based on these rumors. In The Devil's Wind, Manohar Malgonkar gives a sympathetic reconstruction of Nana Saheb's life before, during and after the mutiny as told in his own words.[18] Another novel Recalcitrance published in 2008 the 150th anniversary year of the Great Uprising of 1857 and written by Anurag Kumar shows a character similar to Nana Sahab receiving blessings from an Indian sage who also gives him a special boon connected to his life and the battle of 1857.

After the independence of India, Nana Sahib was hailed as a freedom fighter, and the Nana Rao Park in Kanpur was constructed in honor of Nana Sahib and his brother, Bala Rao.

Belsare's account

Shree K. V. Belsare's book on the Maharashtrian Saint Shree Brahmachaitanya Gondhavalekar Maharaj states that after losing the battle with the British, Shree Nanasaheb Peshwe went to Naimisharanya, the Naimisha Forest in the vicinity of Sitapur, Uttar Pradesh where he met Shree Gondhavalekar Maharaj, who assured Shree Nanasaheb Tumachya Kesala dhakka lagnar naahi. Ya pudhil ayushya tumhi Bhagavantachya chintana madhe ghalavave. Me tumachya antakali hajar asen.(No one can harm you now. You should spend rest of your life in God's service. I will be near you at your last breath) Shree Nanasaheb then was living in a cave in Naimisharanya with his 2 servants (from 1860 to 1906, until his death). According to the book, he died on 30th / 31st Oct / 1st Nov 1906 at the age of 81 years, when Shree Gondhavalekar Maharaj was present with him. Shree Maharaj performed all his rituals.

Initially Shree Nanasaheb was very much upset from losing the kingdom in battle with the British. But Shree Gondhavalekar Maharaj explained to him the "Wish of God". He said, "It is very sad that Nanasaheb had to lose the battle and the kingdom in such a tragic way, but fighting with the British is totally different than fighting with Mughals. People from the middle class who know the British language will lead the next freedom war against British. Soon they will come into the picture. Your role as King or warrior has finished, and now you need to focus on the 'internal war'." Initially it was very difficult for him to accept this fact, but slowly, Nanasaheb accepted this and made progress on the path to God. He was staying in the cave along with his 2 servants who used to go to Ayodhya to bring newspapers (Kesari) and foodstuffs. Nanansaheb used to visit "Pashupatinath" in Nepal and to meet his family - Samsherbahaddar & wife.[19]

The Sihor account and secret

But a critical fact and secret remains intact, that is Nana Sahib's remnants at Sihor in Bhavnagar District of Gujarat. Undocumented material also suggests Nana Sahib would keep changing his location between Sihor and interior Shatrunjaya Hills around Palitana periodically. However, references, mentions and evidences of Nana Sahib's consistent stay in Sihor have been more dominant and documented in regional records and articles at regular intervals since many decades, for he spent his rest of the life in Sihor, initially as a sage. There were some active freedom fighters and volunteers from Sihor during British rule, and one of them, had he been associated with Nana Sahib is often anticipated to have facilitated Nana Sahib's hideout and his group's safe passage to Sihor during early 60's (1860's), while he would leave Nepal and striving to settle out against British aggression in North India and Kanpur which became evident post 1857.

Sihor was a place still quiet, serene, surrounded by hills, with difficult passages and forests stretching up to Girnar range. Religiously to interview the land and region of Kathiawar or the Saurashtra (region), this province often known for its nobility, bravery, sacrifice and spirituality, the place of Sihor in Bhavnagar, Kathiawar, its dormant hills and the jungle surrounding the town may have been a better option and success for Nana Sahib and his allies to settle out there post 1857 revolt and after leaving Nepal. Also with the fact Sihor and its people had continuing connections with Mumbai and various parts of now Maharashtra, which in turn seemed to have helped Nana Sahib to keep a regular touch with few his allies down in Mumbai and Maharashtra. This may be seen from the correspondence, people who kept coming to meet him in Sihor.

As per the records of Sihor history, Nana Sahib passed away in 1909 in Sihor, but curiosity, facts and revelations had started emerging peculiarly post 1947 across the region (Sihor) and Saurashtra, with some official efforts starting toward the 70's (1970's). Subsequently, opening of more links, correspondence, his writings, a few empirical archives, documents with the then state of Bhavnagar, few his rare photographs, some events, altogether a reasonable span of his stay of 45 years in Sihor, and Nana Sahib's local as well as national allies & revolutionaries found reference, nearly to establish without efforts in an unbiased manner, the most probable account of disappearance of this historical figure. Most critically when all these secrets were rather for keeping them as secret and not for the claims, either to prove a personality as Nana Sahib or reveal if it was Sihor which was marked by Nana Sahib's remainder of life, which almost carried along for 45-46 years.

Among the locals, very interesting piece of history referring the remainder, Nana Sahib's life in Sihor, his character, his thoughts and deeds, his subtle nature and identity, his local and general involvement, all these conveyed by those who were close to him directly or indirectly in Sihor, periodically got published in the region. Adding to that, some steps and initiatives taken by him, and the belongings & remnants, these all when acknowledged and realized later, post 1947, eventually to acknowledge they were just Nana Sahib, are all a serious subject of learning and retrospection. This account poses re-evaluation of an incomplete task, a structured approach and serious initiative in asking for the state government of Gujarat and the Central Government, India.

Presently, there is a house signified to Nana Sahib in old town of Sihor, remnants and materials, an old tomb as a tribute to him by the locals, a few existing connections/references and recently a recreational park named after Nana Sahib Peshwa in Sihor.

Preceded by

Bajirao IIPeshwa

1851-1857Succeeded by

noneReferences

- ^ |url=http://www.britishempire.co.uk/forces/armycampaigns/indiancampaigns/mutiny/cawnpore.htm |title=The Indian Mutiny: The Siege of Cawnpore |accessdate=2007-07-11 }}

- ^ Brock, William (1858). A Biographical Sketch of Sir Henry Havelock, K. C. B.. Tauchnitz. http://books.google.com/?id=GZEDAAAAQAAJ. Retrieved 2007-07-12.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "The Indian Mutiny: The Siege of Cawnpore". http://www.britishempire.co.uk/forces/armycampaigns/indiancampaigns/mutiny/cawnpore.htm. Retrieved 2007-07-11.

- ^ a b c d e f Wright, Caleb (1863). Historic Incidents and Life in India. J. A. Brainerd. pp. 239. ISBN 9781135723125. http://books.google.com/?id=umULAAAAIAAJ.

- ^ Mukherjee, Rudrangshu (August 1990). ""Satan Let Loose upon Earth": The Kanpur Massacres in India in the Revolt of 1857". Past and Present 128: 92–116. doi:10.1093/past/128.1.92.

- ^ a b "Echoes of a Distant war". The Financial Express. 2007-04-08. http://www.financialexpress.com/fe_full_story.php?content_id=160464. Retrieved 2007-07-11.

- ^ Hibbert, Christopher (1978). The Great Mutiny: India, 1857. Viking Press. pp. 194. ISBN 0670349836.

- ^ a b Nayar, Pramod K. (2007). The Great Uprising. Penguin Books, India. ISBN 978-0143102380.

- ^ G. W. Williams, "Memorandum", printed with Narrative of the Events in the NWP in 1857-58 (Calcutta, n.d.), section on Cawnpore (hereafter Narrative Kanpur), p. 20: "A man of great influence in the city, and a government official, has related a circumstance that is strange, if true, viz. that whilst the massacre was being carried on at the ghat, a trooper of the 2nd Cavalry, reported to the Nana, then at Savada house, that his enemies, their wives and children were exterminated ... On hearing which, the Nana replied, that for the destruction of women and children, there was no necessity' and directed the sowar to return with an order to stay their slaughter". See also J. W. Kaye, History of the Sepoy War in India, 1857-58, 3 vols. (Westport, 1971 repr.), ii, p. 258. (This reprint of Kaye's work carries the title History of the Indian Mutiny of 1857-58.)

- ^ a b c Brock, William (1858). A Biographical Sketch of Sir Henry Havelock, K. C. B.. Tauchnitz. pp. 150–152. http://books.google.com/?id=GZEDAAAAQAAJ. Retrieved 2007-07-12.

- ^ a b English, Barbara (February 1994). "The Kanpur Massacres in India in the Revolt of 1857". Past and Present 143: 169–178. doi:10.1093/past/142.1.169.

- ^ a b c d V. S. "Amod" Saxena (2003-02-17). "Revolt and Revenge; a Double Tragedy (delivered to The Chicago Literary Club)". http://www.chilit.org/SAXENA1.HTM. Retrieved 2007-07-11.

- ^ Mukherjee, Rudrangshu (February 1994). "The Kanpur Massacres in India in the Revolt of 1857: Reply". Past and Present 142: 178–189. doi:10.1093/past/142.1.178.

- ^ Ward, Andrew (1996). Our Bones Are Scattered: The Cawnpore Massacres and The Indian Mutiny Of 1857. Henry Holt. ISBN 0805024379.

- ^ "India Rising: Horrors & atrocities". National Army Museum, Chelsea. http://www.national-army-museum.ac.uk/exhibitions/indiaRising/page10.shtml. Retrieved 2007-07-11.

- ^ "The South Australian Advertiser, Monday 12 March 1860". http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article1203098. Retrieved 2010-03-04.

- ^ Wright, Daniel (1993). History of Nepal: With an Introductory Sketch of the Country and People of Nepal. Asian Educational Services. pp. 64. ISBN 8120605527.

- ^ Manohar Malgonkar (1972). The Devil's Wind. Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 0241021766,.

- ^ K.V.Belsare, Brahmachaitanya Shree Gondhavalekar Maharaj - Charitra & Vaagmay

Further reading

- Gupta, Pratul Chandra (1963). Nana Sahib and the Rising at Cawnpore. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198215231.

- Shastitko, Petr Mikhaĭlovich; Savitri Shahani (1980). Nana Sahib: An Account of the People's Revolt in India, 1857-1859. Shubhada-Saraswat Publications.

Maratha Empire Rulers Peshwas Moropant Pingle · Ramchandra Pant Amatya · Bahiroji Pingale · Parshuram Tribak Kulkarni · Balaji Vishwanath · Bajirao · Balaji Bajirao · Madhavrao Ballal · Narayanrao · Raghunathrao · Sawai Madhavrao · Baji Rao II · Amrutrao · Nana SahibMaratha Confederacy (Subsidiary or Feudatory states) Battles Pratapgarh · Kolhapur · Pavan Khind · Surat · Sinhagad · Palkhed · Mandsaur · 1st Delhi · Vasai · Trichinopoly · Expeditions in Bengal · 3rd Panipat · Rakshabhuvan · Panchgaon · Gajendragad · Lalsot · Patan · Kharda · Poona · 2nd Delhi · Assaye · Laswari · Farrukhabad · Bharatpur · Khadki · Koregaon · Mahidpur · Maratha-Mysore War · full list ·Wars Adversaries Adilshahi · Mughal Empire · Durrani Empire · British Empire · Portuguese Empire · Hyderabad · Sultanate of MysoreForts Categories:- Hindu warriors

- Maratha warriors

- Revolutionaries of Indian Rebellion of 1857

- People from Kanpur

- Jules Verne

- 1906 deaths

- 1824 births

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.