- Erythritol

-

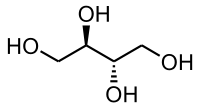

Erythritol  (2R,3S)-butane-1,2,3,4-tetraol

(2R,3S)-butane-1,2,3,4-tetraolIdentifiers CAS number 10030-58-7  , [], []

, [], []ChemSpider 192963

UNII RA96B954X6

DrugBank DB04481 KEGG D08915

ChEBI CHEBI:17113

ChEMBL CHEMBL349605

Jmol-3D images Image 1

Image 2- OC[C@@H](O)[C@@H](O)CO

C([C@H]([C@H](CO)O)O)O

Properties Molecular formula C4H10O4 Molar mass 122.12 g mol−1 Density 1.45 g/cm³ Melting point 121 °C, 394 K, 250 °F

Boiling point 329-331 °C, 602-604 K, 624-628 °F

(verify) (what is:

(verify) (what is:  /

/ ?)

?)

Except where noted otherwise, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C, 100 kPa)Infobox references Erythritol ((2R,3S)-butane-1,2,3,4-tetraol) is a sugar alcohol (or polyol) that has been approved for use as a food additive in the United States[1] and throughout much of the world. It was discovered in 1848 by British chemist John Stenhouse.[2] It occurs naturally in some fruits and fermented foods.[3] At the industrial level, it is produced from glucose by fermentation with a yeast, Moniliella pollinis.[1] It is 60–70% as sweet as table sugar yet it is almost non-caloric, does not affect blood sugar, does not cause tooth decay, and is partially absorbed by the body, excreted in urine and feces. It is less likely to cause gastric side-effects than other sugar alcohols, although a 50g dose caused a significant increase in the number of test subjects reporting nausea and borborygmi.[4] Under U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) labeling requirements, it has a caloric value of 0.2 kilocalories per gram (95% less than sugar and other carbohydrates), though nutritional labeling varies from country to country. Some countries like Japan and the United States label it as zero-calorie, while European Union regulations currently label it and all other sugar alcohols at 2.4 kcal/g.

Contents

Erythritol and human digestion

In the body, most of the erythritol is absorbed into the bloodstream in the small intestine, and then for the most part excreted unchanged in the urine. About 10% enters the colon.[5] Because 90% of erythritol is absorbed before it enters the large intestine, it does not normally cause laxative effects, as are often experienced after consumption of other sugar alcohols (such as xylitol and maltitol).[6]

Side effects

Doses over 50g can cause a significant increase in nausea and borborygmi,[4] and (rarely) erythritol can cause allergic urticaria.[7]

In general, erythritol is free of side-effects in regular use. Erythritol, when compared with other sugar alcohols, is also much more difficult for intestinal bacteria to digest, so it is less likely to cause gas or bloating than other polyols,[8] such as maltitol, sorbitol, or lactitol.

Physical properties

Heat of solution

Erythritol has a strong cooling effect (endothermic, or positive heat of solution[9]) when it dissolves in water, which is often combined with the cooling effect of mint flavors but proves distracting with more subtle flavors and textures. The cooling effect is only present when erythritol is not already dissolved in water, a situation that might be experienced in an erythritol-sweetened frosting, chocolate bar, chewing gum, or hard candy. When combined with solid fats, such as coconut oil, cocoa butter, or cow's butter, the cooling effect tends to accentuate the waxy characteristics of the fat in a generally undesirable manner.[citation needed] This is particularly pronounced in chocolate bars made with erythritol.[citation needed] The cooling effect of erythritol is very similar to that of xylitol and among the strongest cooling effects of all sugar alcohols.[10]

Blending for sugar-like properties

Erythritol is commonly used as a medium in which to deliver high-intensity sweeteners, especially stevia derivatives, serving the dual function of providing both bulk and a flavor similar to that of table sugar. Diet beverages made with this blend, thus, contain erythritol in addition to the main sweetener. Beyond high-intensity sweeteners, erythritol is often paired with other bulky ingredients that exhibit sugar-like characteristics to better mimic the texture and mouthfeel of sucrose. The cooling effect of erythritol is rarely desired, hence other ingredients are chosen to dilute or negate that effect. Erythritol also has a propensity to crystallize and is not as soluble as sucrose, so ingredients may also be chosen to help negate this disadvantage. Furthermore, erythritol is non-hygroscopic, meaning it does not attract moisture, which can lead to the drying out of products, in particular baked goods, if another hygroscopic ingredient is not used in the formulation.

Inulin is oftentimes combined with erythritol due to inulin's offering a complementary negative heat of solution (exothermic, or warming effect when dissolved, which helps cancel erythritol's cooling effect) and non-crystallizing properties. However, inulin has a propensity to cause gas and bloating in those having consumed it in moderate to large quantities, in particular in individuals unaccustomed to it. Other sugar alcohols are sometimes used with erythritol, in particular isomalt due to its minimally positive heat of solution, and glycerin, which has a negative heat of solution, moderate hygroscopicity, and non-crystallizing liquid form.

Erythritol and bacteria

Erythritol has been certified as tooth-friendly.[11] The sugar alcohol cannot be metabolized by oral bacteria, and so does not contribute to tooth decay. It is interesting to note that erythritol exhibits some, but not all, of xylitol's tendency to "starve" harmful bacteria. Unlike xylitol, erythritol is actually absorbed into the bloodstream after consumption but before excretion.[citation needed] However, it is not clear at present if the effect of starving harmful bacteria occurs systemically.

See also

- Threitol, the diastereomer of erythritol

- Stevia

References

- ^ a b FDA/CFSAN: Agency Response Letter: GRAS Notice No. GRN 000076

- ^ The discovery of erythritol, which Stenhouse called "erythroglucin", was announced in: Stenhouse, John (January 1, 1848). "Examination of the proximate principles of some of the lichens". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 138: 63–89; see especially p. 76.

- ^ Shindou, T., Sasaki, Y., Miki, H., Eguchi, T., Hagiwara, K., Ichikawa, T. (1988). "Determination of erythritol in fermented foods by high performance liquid chromatography". Shokuhin Eiseigaku Zasshi 29 (6): 419–422.

- ^ a b Storey, D.; Lee, A.; Bornet, F.; Brouns, F. (Mar 2007). "Gastrointestinal tolerance of erythritol and xylitol ingested in a liquid.". Eur J Clin Nutr 61 (3): 349–54. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602532. PMID 16988647.

- ^ Arrigoni, E.; Brouns, F.; Amadò, R. (Nov 2005). "Human gut microbiota does not ferment erythritol.". Br J Nutr 94 (5): 643–6. PMID 16277764.

- ^ Munro IC, Berndt WO, Borzelleca JF, et al. (December 1998). "Erythritol: an interpretive summary of biochemical, metabolic, toxicological and clinical data". Food Chem. Toxicol. 36 (12): 1139–74. doi:10.1016/S0278-6915(98)00091-X. PMID 9862657. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S027869159800091X.

- ^ Hino, H.; Kasai, S.; Hattori, N.; Kenjo, K. (Mar 2000). "A case of allergic urticaria caused by erythritol.". J Dermatol 27 (3): 163–5. PMID 10774141.

- ^ Arrigoni E, Brouns F, Amadò R (November 2005). "Human gut microbiota does not ferment erythritol". Br. J. Nutr. 94 (5): 643–6. PMID 16277764. http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0007114505002291.

- ^ Wohlfarth, Christian (2006). CRC handbook of enthalpy data of polymer-solvent systems. CRC/Taylor & Francis. pp. 3–. ISBN 9780849393617. http://books.google.com/books?id=e2XyFi-bMY8C&pg=PA3.

- ^ Jasra,R.V.; Ahluwalia, J.C. 1982. Enthalpies of Solution, Partial Molal Heat Capacities and Apparent Molal Volumes of Sugars and Polyols in Water. Journal of Solution Chemistry, 11( 5): 325-338. Template:ISSN 1572-8927

- ^ Kawanabe J, Hirasawa M, Takeuchi T, Oda T, Ikeda T (1992). "Noncariogenicity of erythritol as a substrate". Caries Res. 26 (5): 358–62. PMID 1468100.

Categories:- Food additives

- Sweeteners

- Sugar alcohols

- OC[C@@H](O)[C@@H](O)CO

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.