- Terra Australis

-

Terra Australis

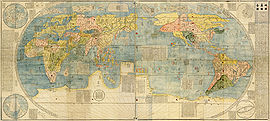

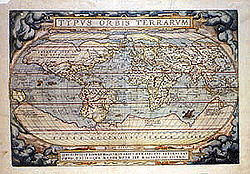

Terra Australis is the large continent on the bottom of this 1570 map.Type Hypothetical continent Terra Australis, Terra Australis Ignota or Terra Australis Incognita (Latin for "the unknown land of the South") was a hypothesized continent appearing on European maps from the 15th to the 18th century. Other names for the continent include Magallanica or Magellanica ("the land of Magellan"), La Australia del Espíritu Santo (Spanish: "the southern land of the Holy Spirit"), and La grande isle de Java (French: "the great island of Java"). Terra Australis was one of several names applied to the actual continent of Australia, after its European discovery; it is the root of the continent's modern name (see Etymology, at Australia).

Contents

Origins

The notion of Terra Australis was introduced by Aristotle[citation needed]. His ideas were later expanded by Ptolemy (1st century AD), who believed that the Indian Ocean was enclosed on the south by land, and that the lands of the Northern Hemisphere should be balanced by land in the south.[1] Ptolemy's maps, which became well-known in Europe during the Renaissance, did not actually depict such a continent, but they did show an Africa which had no southern oceanic boundary (and which therefore might extend all the way to the South Pole), and also raised the possibility that the Indian Ocean was entirely enclosed by land. Christian thinkers did not discount the idea that there might be land beyond the southern seas, but the issue of whether it could be inhabited was controversial.

Mapping the Southern Continent

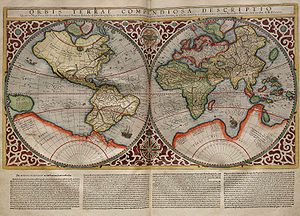

Explorers of the Age of Discovery, from the late 15th century on, proved that Africa was almost entirely surrounded by sea, and that the Indian Ocean was accessible from both west and east. These discoveries reduced the area where the continent could be found; however, many cartographers held to Aristotle's opinion. Scientists, such as Gerardus Mercator (1569) and Alexander Dalrymple as late as 1767[1] argued for its existence, with such arguments as that there should be a large landmass in the south as a counterweight to the known landmasses in the Northern Hemisphere. As new lands were discovered, they were often assumed to be parts of the hypothetical continent.

Terra Australis was depicted on the mid-16th-century Dieppe maps, where its coastline appeared just south of the islands of the East Indies; it was often elaborately charted, with a wealth of fictitious detail. There was much interest in Terra Australis among Norman and Breton merchants at that time. In 1566 and 1570, Francisque and André d'Albaigne presented Gaspard de Coligny, Admiral of France, with projects for establishing relations with the Austral lands. Although the Admiral gave favourable consideration to these initiatives, they came to nought when Coligny was killed in 1572.[2]

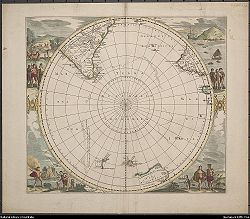

Juan Fernandez, sailing from Chile in 1576, claimed he had discovered the Southern Continent.[3] The Polus Antarcticus map of 1641 by Henricus Hondius, bears the inscription: ”Insulas esse a Nova Guinea usque ad Fretum Magellanicum affirmat Hernandus Galego, qui ad eas explorandas missus fuit a Rege Hispaniae Anno 1576 (Hernando Gallego, who in the year 1576 was sent by the King of Spain to explore them, affirms that there are islands from New Guinea up to the Strait of Magellan)”.[4]

Luis Váez de Torres, a Galician or Portuguese navigator working for the Spanish Crown, proved the existence of a passage south of New Guinea, now known as Torres Strait.

Pedro Fernandes de Queirós, another Portuguese navigator sailing for the Spanish Crown, saw a large island south of New Guinea in 1606, which he named La Australia del Espiritu Santo. He represented this to the King of Spain as the Terra Australis incognita.

Isaac and Jacob Le Maire established the Australische Compagnie (Australian Company) in 1615 to trade with Terra Australis, which they called "Australia".[5]

British Admiralty Hydrographer Alexander Dalrymple, whilst translating some Spanish documents captured in the Philippines in 1752, found de Torres's testimony. This discovery led Dalrymple to publish the Historical Collection of the Several Voyages and Discoveries in the South Pacific Ocean in 1770-1771. Dalrymple presented a beguiling tableau of the Terra Australis, or Southern Continent:

The number of inhabitants in the Southern Continent is probably more than 50 millions, considering the extent, from the eastern part discovered by Juan Fernandez, to the western coast seen by Tasman, is about 100 deg. of longitude, which in the latitude of 40 deg. amounts to 4596 geographic, or 5323 stature miles. This is a greater extent than the whole civilized part of Asia, from Turkey to the eastern extremity of China. There is at present no trade from Europe thither, though the scraps from this table would be sufficient to maintain the power, dominion, and sovereignty of Britain, by employing all its manufacturers and ships. Whoever considers the Peruvian empire, where arts and industry flourished under one of the wisest systems of government, which was founded by a stranger, must have very sanguine expectations of the southern continent, from whence it is more than probable Mango Capac, the first Inca, was derived, and must be convinced that the country, from whence Mango Capac introduced the comforts of civilized life, cannot fail of amply rewarding the fortunate people who shall bestow letters instead of quippos (quipus), and iron in place of more awkward substitutes.[6]

Dalrymple's claim of the existence of an unknown continent aroused widespread interest and prompted the British government in 1769 to order James Cook in HM Bark Endeavour to seek out the Southern Continent to the South and West of Tahiti.[7] The expedition eventually led in 1770 to the British discovery and charting of the Eastern coastline of Australia.

The cartographic depictions of the southern continent in the 16th and early 17th centuries, as might be expected for a concept based on such abundant conjecture and minimal data, varied wildly from map to map; in general, the continent shrank as potential locations were reinterpreted. At its largest, the continent included Tierra del Fuego, separated from South America by a small strait; New Guinea; and what would come to be called Australia. In Ortelius's atlas Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, published in 1570, Terra Australis extends north of the Tropic of Capricorn in the Pacific Ocean.

As long as it appeared on maps at all, the continent minimally included the unexplored lands around the South Pole, but generally much larger than the real Antarctica, spreading far north – especially in the Pacific Ocean. New Zealand, first seen by the Dutch explorer Abel Tasman in 1642, was regarded by some as a part of the continent.

Decline of the idea

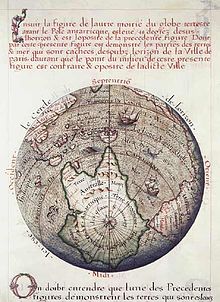

The available territory for a southern continent had diminished greatly in this 1657 map by Jan Janssonius. Terra Australis Incognita ("unknown southern land") is printed across a region including the south pole without any definite shorelines.

The available territory for a southern continent had diminished greatly in this 1657 map by Jan Janssonius. Terra Australis Incognita ("unknown southern land") is printed across a region including the south pole without any definite shorelines.

Over the centuries the idea of Terra Australis gradually lost its hold. In 1615, Jacob le Maire and Willem Schouten's rounding of Cape Horn proved that Tierra del Fuego was a relatively small island, while in 1642 Abel Tasman's first pacific voyage proved that Australia was not part of the mythical southern continent. Much later, James Cook sailed around most of New Zealand in 1770, showing that even it could not be part of a large continent. On his second voyage he circumnavigated the globe at a very high southern latitude, at some places even crossing the south polar circle, showing that any possible southern continent must lie well within the cold polar areas. There could be no extension into regions with a temperate climate, as had been thought before. In 1814, Matthew Flinders published the book A Voyage to Terra Australis in which he wrote:

- "There is no probability, that any other detached body of land, of nearly equal extent, will ever be found in a more southern latitude; the name Terra Australis will, therefore, remain descriptive of the geographical importance of this country, and of its situation on the globe: it has antiquity to recommend it; and, having no reference to either of the two claiming nations, appears to be less objectionable than any other which could have been selected.*"

...with the accompanying note at the bottom of the page:

- "* Had I permitted myself any innovation upon the original term, it would have been to convert it into AUSTRALIA; as being more agreeable to the ear, and an assimilation to the names of the other great portions of the earth."

Flinders had concluded that the Terra Australis as hypothesized by Aristotle and Ptolemy did not exist, so he wanted the name applied to what he saw as the next best thing: "Australia". His conclusion would soon be revealed as a mistake, but by that time the name had stuck.[8]

Antarctica

Antarctica was finally sighted in the hypothetical area of Terra Australis on January 27, 1820 by Russian Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen, the first confirmed sighting.

See also

- Ancient world maps

- Terra Incognita

- Terra pericolosa

- History of cartography

- List of cartographers

- Lost continent

- Regio Patalis

References

- ^ a b John Noble Wilford: The Mapmakers, the Story of the Great Pioneers in Cartography from Antiquity to Space Age, p. 139, Vintage Books, Random House 1982, ISBN 0-394-75303-8

- ^ E.T. Hamy, "Francisque et André d'Albaigne: cosmographes lucquois au service de la France"; "Nouveau documents sur les frères d'Albaigne et sur le projet de voyage et de découvertes présenté à la cour de France"; and "Documents relatifs à un projet d’expéditions lointaines présentés à la cour de France en 1570", in Bulletin de Géographie Historique et Descriptive, Paris, 1894, p. 405–433; 1899, p. 101–110; and 1903, p. 266–273.

- ^ José Toribio Medina, El Piloto Juan Fernandez, Santiago de Chile, 1918, reprinted by Gabriela Mistral, 1974, pp. 136, 246.

- ^ An on-line image of this map is at: http://nla.gov.au/nla.map-t732.

- ^ Spieghel der Australische Navigatie; cited by A. Lodewyckx, "The Name of Australia: Its Origin and Early Use", The Victorian Historical Magazine, Vol. XIII, No. 3, June 1929, pp. 100–191.

- ^ Alexander Dalrymple, An Historical Collection of the several Voyages and Discoveries in the South Pacific Ocean, Vol.I, London, 1769 and 1770, p.xxviii-xxix.

- ^ Andrew Cook, Introduction to An account of the discoveries made in the South Pacifick Ocean / by Alexander Dalrymple ; first printed in 1767, reissued with a foreword by Kevin Fewster and an essay by Andrew Cook, Potts Point (NSW), Hordern House Rare Books for the Australian National Maritime Museum, 1996, pp. 38–9.

- ^ Avan Judd Stallard, “Origins of the Idea of Antipodes: Errors, Assumptions, and a Bare Few Facts”, Terrae Incognitae, Volume 42, Number 1, September 2010, pp.34-51.

Continents Historical continentsArctica · Asiamerica · Atlantica · Avalonia · Baltica · Cimmeria · Congo craton · Euramerica · Kalaharia · Kazakhstania · Laurentia · North China · Siberia · South China · East Antarctica · IndiaSubmerged continents

Kerguelen Plateau · ZealandiaMythical and theorized continents

Atlantis · Kumarikkandam · Lemuria · Meropis · Mu · Terra AustralisSee also Regions of the worldCategories:- History of Australia before 1788

- History of Australia (1788–1850)

- History of Antarctica

- Phantom islands

- Theoretical continents

- Cartography

- Latin words and phrases

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.