- Days of Heaven

-

Days of Heaven

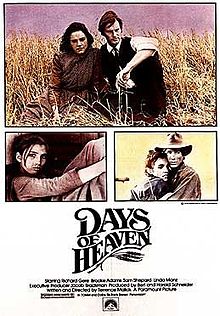

Theatrical release posterDirected by Terrence Malick Produced by Bert Schneider

Harold SchneiderWritten by Terrence Malick Starring Richard Gere

Brooke Adams

Sam Shepard

Linda ManzMusic by Ennio Morricone Cinematography Néstor Almendros

Haskell WexlerEditing by Billy Weber Distributed by Paramount Pictures Release date(s) September 13, 1978 Running time 90 minutes Country United States Language English Budget $3,000,000[1] Box office $3,446,749[2] Days of Heaven is a 1978 American romantic drama film written and directed by Terrence Malick and starring Richard Gere, Brooke Adams, Sam Shepard and Linda Manz. Set in the early 20th century, it tells the story of two poor lovers, Bill and Abby, as they travel to the Texas Panhandle to harvest crops for a wealthy farmer. Bill encourages Abby to claim the fortune of the dying farmer by tricking him into a false marriage. This results in an unstable love triangle and a series of unfortunate events.

Days of Heaven is widely recognized as a landmark of 1970s cinema.

Contents

Plot

The story is set in 1916.[3] Bill (Gere), a Chicago manual laborer, knocks down and kills a boss in the steel mill where he works. He flees to the Texas Panhandle with his girlfriend Abby (Adams) and younger sister Linda (Manz). Bill and Abby pretend to be siblings to prevent gossip.

The three hire on as part of a large group of seasonal workers with a rich, shy farmer (Shepard). The farmer learns that he is dying of an unspecified disease. When he falls in love with Abby, Bill encourages her to marry him so that they can inherit his money after he dies. The marriage takes place and Bill stays on the farm as Abby's "brother." The farmer's foreman suspects their scheme. The farmer's health unexpectedly remains stable, foiling Bill's plans.

Eventually, the farmer discovers Bill's true relationship with Abby. At the same time, Abby has begun to fall in love with her new husband. After a locust swarm and a fire destroy his wheat fields, the farmer goes after Bill with a gun, but Bill kills him. Bill then flees with Abby and Linda. The foreman and the police pursue and eventually find them, and the police kill Bill. Abby leaves Linda at a boarding school and goes off on her own.

Cast

- Richard Gere as Bill

- Brooke Adams as Abby

- Sam Shepard as The Farmer

- Linda Manz as Linda

- Robert J. Wilke as The Farm Foreman

- Jackie Shultis as Linda's Friend

- Stuart Margolin as Mill Foreman

- Timothy Scott as Harvest Hand

- Gene Bell as Dancer

- Doug Kershaw as Fiddler

- Richard Libertini as Vaudeville Leader

Production

Producer Jacob Brackman introduced fellow producer Bert Schneider to filmmaker Terrence Malick in 1975.[4] On a trip to Cuba, Schneider and Malick began conversations that would lead to the development of Days of Heaven. Malick had tried and failed to get Dustin Hoffman or Al Pacino to star in the film. Schneider agreed to produce the film. He and Malick cast a young Richard Gere, actor and playwright Sam Shepard and Brooke Adams. Paramount Pictures CEO Barry Diller wanted Schneider to produce films for him and agreed to finance Days of Heaven. At the time, the studio was headed in a new direction. They were hiring new production heads who had worked in network television, and, according to former production chief Richard Sylbert, "[manufacturing] product aimed at your knees".[4] Despite the change in direction, Schneider was able to secure a deal with Paramount by guaranteeing the budget and taking personal responsibility for all overages. "Those were the kind of deals I liked to make", Schneider said, "because then I could have final cut and not talk to nobody about why we're gonna use this person instead of that person."[4]

Malick admired cinematographer Nestor Almendros' work on The Wild Child and wanted him to shoot Days of Heaven.[5] He was impressed by Malick's knowledge of photography and willingness to use little studio lighting. The two men modeled the film's cinematography after silent films, which often used natural light. They also drew inspiration from painters such as Johannes Vermeer, Edward Hopper (particularly his House by the Railroad), and Andrew Wyeth, as well as photo-reporters from the turn of the century.[5]

Principal photography

Production began in the fall of 1976.[6] Though the film was set in Texas, the exteriors were shot in Whiskey Gap, a ghost town on the prairie of Alberta, Canada and a final scene shot on the grounds of Heritage Park Historical Village in Calgary.[7] Jack Fisk designed and built the mansion from plywood in the wheat fields and the smaller houses where the workers lived. The mansion was not a facade, as was normally the custom, but authentically recreated inside and out with period colors: brown, mahogany and dark wood for the interiors.[5] Patricia Norris designed and made the period costumes from used fabrics and old clothes to avoid the artificial look of studio-made costumes.[5]

According to Almendros, the production was not "rigidly prepared", allowing for improvisation.[5] Daily call sheets were not very detailed and the schedule changed to suit the weather. This upset some of the Hollywood crew members not used to working in such a spontaneous way. Most of the crew were used to a "glossy style of photography" and felt frustrated because Almendros did not give them much work.[5] On a daily basis, he asked them to turn off the lights they had prepared for him. Some crew members said that Almendros and Malick did not know what they were doing. Some of the crew quit the production. Malick supported what Almendros was doing and pushed the look of the film further, taking away more lighting aids, and leaving the image bare.[5] Due to union regulations in North America, Almendros was not allowed to operate the camera. With Malick, he would plan out and rehearse movements of the camera and the actors. Almendros would stand near the main camera and give instructions to the camera operators.[5]

Almendros was losing his eyesight by the time shooting began. To evaluate his setups, "he had one of his assistants take Polaroids of the scene, then examined them through very strong glasses".[4] According to Almendros, Malick wanted "a very visual movie. The story would be told through visuals. Very few people really want to give that priority to image. Usually the director gives priority to the actors and the story, but here the story was told through images".[8] Much of the film would be shot during "magic hour", which Almendros called

"a euphemism, because it's not an hour but around 25 minutes at the most. It is the moment when the sun sets, and after the sun sets and before it is night. The sky has light, but there is no actual sun. The light is very soft, and there is something magic about it. It limited us to around twenty minutes a day, but it did pay on the screen. It gave some kind of magic look, a beauty and romanticism".[8]

This "magic look" would extend to interior scenes, which often utilized natural light.

Almendros said,

"In this period there was no electricity. It was before electricity was invented and consequently there was less light. Period movies should have less light. In a period movie the light should come from the windows because that is how people lived."[8]

For the shot in the "locusts" sequence, where the insects rise into the sky, the filmmakers dropped peanut shells from helicopters. They had the actors walk backwards while running the film in reverse through the camera. When it was projected, everything moved forward except the locusts.[9] For the closeups and insert shots, thousands of live locusts were used which had been captured and supplied by the Canadian Department of Agriculture.[5]

While the photography yielded exquisite results, the rest of the production was difficult from the start.[6] The actors and crew reportedly viewed Malick as cold and distant. After two weeks of shooting, Malick was so disappointed with the dailies, he "decided to toss the script, go Leo Tolstoy instead of Fyodor Dostoevsky, wide instead of deep [and] shoot miles of film with the hope of solving the problems in the editing room."[6] In addition, the harvesting machines constantly broke down, which resulted in shooting beginning late in the afternoon, allowing for only a few hours of daylight before it was too dark to go on. One day, two helicopters were scheduled to drop peanut shells that were to simulate locusts on film; however, Malick decided to shoot period cars instead. He kept the helicopters on hold at great cost. Production was lagging behind, with costs exceeding the budget by about $800,000, and Schneider had already mortgaged his home in order to cover the overages.[6]

The production ran so late that both Almendros and camera operator John Bailey had to leave due to a prior commitment on François Truffaut's The Man Who Loved Women. Almendros approached his friend and renowned cinematographer Haskell Wexler to complete the film. They worked together for a week so that Wexler could get familiar with the film's visual style.[5] Wexler was careful to match Almendros' work, but he did make some exceptions. "I did some hand held shots on a Panaflex", he said, "[for] the opening of the film in the steel mill. I used some diffusion. Nestor didn't use any diffusion. I felt very guilty using the diffusion and having (sic) the feeling of violating a fellow cameraman."[8] Though half the finished picture was footage shot by Wexler, he received only credit for "additional photography", much to his chagrin. The credit denied him any chance of an Academy Award for his work on Days of Heaven. He sent critic Roger Ebert a letter "in which he described sitting in a theater with a stopwatch to prove that more than half of the footage" was his.[10]

Post-production

After the production finished principal photography, the editing process took over two years to complete. Malick had a difficult time shaping the film and getting the pieces to go together.[11] Schneider reportedly showed some footage to director Richard Brooks, who was considering Gere for a role in Looking for Mr. Goodbar. According to Schneider, the editing for Days of Heaven took so long that "Brooks cast Gere, shot, edited and released [Looking for Mr. Goodbar] while Malick was still editing".[6] A breakthrough came when Malick experimented with voice-overs from Linda Manz's character, similar to what he had done with Sissy Spacek in Badlands. According to editor Billy Weber, Malick jettisoned much of the film's dialogue, replacing it with Manz's voice-over, which served as an oblique commentary on the story.[6]

After a year, Malick had to call the actors to Los Angeles to shoot inserts of shots that were necessary but had not been filmed in Alberta. The finished film thus includes close-ups of Shephard that were shot under a freeway overpass. The underwater shot of Gere's falling face down into the river was shot in a large aquarium in Sissy Spacek's living room.[7]

Meanwhile, Schneider was upset with Malick. He had confronted Malick numerous times about missed deadlines and broken promises. Due to further cost overruns, he had to ask Paramount for more money, which he preferred not to do. When they screened a demo for Paramount and made their pitch, the studio was impressed and reportedly "gave Malick a very sweet deal at the studio, carte blanche, essentially".[6]

Malick was not able to capitalize on the deal. He was so exhausted from working on the film that he moved to Paris with his girlfriend. He tried developing another project for Paramount, but after a substantial amount of work, he abandoned it. He did not make another film until 1998's The Thin Red Line twenty years later.[11]

Reaction

In his review for The New York Times, Harold C. Schonberg wrote, "Days of Heaven never really makes up its mind what it wants to be. It ends up something between a Texas pastoral and Cavalleria Rusticana. Back of what basically is a conventional plot is all kinds of fancy, self-conscious cineaste techniques."[12] Dave Kehr of The Chicago Reader wrote: "Terrence Malick's remarkably rich second feature is a story of human lives touched and passed over by the divine, told in a rush of stunning and precise imagery. Nestor Almendros's cinematography is as sharp and vivid as Malick's narration is elliptical and enigmatic. The result is a film that hovers just beyond our grasp—mysterious, beautiful, and, very possibly, a masterpiece".[13] Gene Siskel of The Chicago Tribune also wrote that the film "truly tests a film critic's power of description ... Some critics have complained that the Days of Heaven story is too slight. I suppose it is, but, frankly, you don't think about it while the movie is playing".[14] Time magazine's Frank Rich wrote, "Days of Heaven is lush with brilliant images".[15] The periodical went on to name it one of the best films of 1978.[16]

Nick Schager of Slant Magazine has called it "the greatest film ever made."[17] Roger Ebert described the movie as "one of the most beautiful films ever made" and added it on his list of Great Movies.[18]

Days of Heaven held a 93% approval rating at Rotten Tomatoes with an average rating of 8.2/10 based on 45 reviews.[19]

Awards

The film won an Academy Award for Best Cinematography. Per Academy custom the award was given in the name of principal photographer Nestor Almendros.[11] This was somewhat controversial as renowned cinematographer Haskell Wexler also received credit on the film. The film was also nominated for Academy Awards for Costume Design, Original Score, and Sound (John Wilkinson, Robert W. Glass, Jr., John T. Reitz and Barry Thomas).[20] Malick won the Prix de la mise en scène (Best Director award) at the 1979 Cannes Film Festival.[21] Furthermore, he was named the best director by the National Society of Film Critics.

In 2007, Days of Heaven was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

Notes

- ^ http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0077405/business

- ^ http://www.boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=daysofheaven.htm

- ^ The film shows a 1916 newspaper, and a scene late in the film shows American soldiers headed off for World War I.

- ^ a b c d Biskind 1998, p. 296.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Almendros 1986

- ^ a b c d e f g Biskind 1998, p. 297.

- ^ a b Almereyda, Michael (April 13, 2004). "After The Rehearsal: Flirting with Disaster: Discussing Days of Heaven and Dylan classics with Sam Shepard". Village Voice. Archived from the original on December 23, 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5vB9iCJez. Retrieved April 17, 2006.

- ^ a b c d Glassman, Arnold; Todd McCarthy, Stuart Samuels (1992). "Visions of Light: The Art of Cinematography". Kino International.

- ^ Thompson, Rustin (June 30, 1998). "Myth-making With Natural Light". Moviemaker. Archived from the original on December 23, 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5vB9c8biT. Retrieved February 13, 2009.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (December 7, 1997). "Days of Heaven: Great Movies". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on December 23, 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5vB9nB5PF. Retrieved September 19, 2007.

- ^ a b c Biskind, Peter (August 1999). "The Runaway Genius". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on December 23, 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5vB9qbjx8. Retrieved April 22, 2010.

- ^ Schonberg, Harold C (September 14, 1978). "Days of Heaven". The New York Times. http://movies.nytimes.com/movie/review?_r=2&res=EE05E7DF173EE767BC4C52DFBF668383669EDE&partner=Rotten%20Tomatoes. Retrieved December 11, 2008.

- ^ Kehr, Dave (1978). "Days of Heaven". The Chicago Reader. Archived from the original on December 23, 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5vB9tXN6P. Retrieved December 11, 2008.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (October 9, 1978). "Days of Heaven". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ Rich, Frank (September 18, 1978). "Days of Heaven". Time. Archived from the original on December 23, 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5vBA4XKHV. Retrieved September 9, 2009.

- ^ "Cinema: Year's Best". Time. January 1, 1979. Archived from the original on December 23, 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5vBA6v6Hh. Retrieved September 9, 2009.

- ^ Schager, Nick (October 22, 2007). "Days of Heaven review". Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on December 23, 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5vBAIbjN1. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- ^ "Days of Heaven (1978)". Chicago Sun-Times. http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=%2F19971207%2FREVIEWS08%2F401010327%2F1023.

- ^ "Days of Heaven (1978)". Rotten Tomatoes. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/days_of_heaven/. Retrieved October 15, 2011.

- ^ "The 51st Academy Awards (1979) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. http://www.oscars.org/awards/academyawards/legacy/ceremony/51st-winners.html. Retrieved 2011-10-06.

- ^ "Sweeping Cannes". Time. June 4, 1979. Archived from the original on December 23, 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5vBATPd59. Retrieved September 9, 2009.

References

- Almendros, Nestor (1986) A Man with a Camera. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Biskind, Peter (1998) Easy Riders, Raging Bulls. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Further reading

- Charlotte Crofts (2001), 'From the "Hegemony of the Eye" to the "Hierarchy of Perception": The Reconfiguration of Sound and Image in Terrence Malick's Days of Heaven', Journal of Media Practice, 2:1, 19-29.

- Terry Curtis Fox (1978), 'The Last Ray of Light', Film Comment, 14:5, Sept/Oct, 27-28.

- Martin Donougho (1985), 'West of Eden: Terrence Malick's Days of Heaven', Postscript: Essays in Film and the Humanities, 5:1, Fall, 17-30.

- Terrence Malick (1976), Days of Heaven, Script registered with the Writers Guild of America, 14 Apr; revised 2 Jun.

- Brooks Riley (1978), 'Interview with Nestor Almendros', Film Comment, 14:5, Sept/Oct, 28-31.

- Janet Wondra (1994), 'A Gaze Unbecoming: Schooling the Child for Femininity in Days of Heaven', Wide Angle, 16:4, Oct, 5-22.

External links

- Days of Heaven at the Internet Movie Database

- Days of Heaven at AllRovi

- Days of Heaven at Rotten Tomatoes

- Days of Heaven at Box Office Mojo

- Essay by Katy Karpfinger for New Linear Perspectives

- Essay by Adrian Martin for the Criterion Collection

Terrence Malick Feature films Badlands (1973) • Days of Heaven (1978) • The Thin Red Line (1998) • The New World (2005) • The Tree of Life (2011)Short films Lanton Mills (1969)Productions Endurance (1999) • Happy Times (2000) • The Endurance: Shackleton's Legendary Antarctic Expedition (2000) • The Beautiful Country (2004) • Undertow (2004) • Amazing Grace (2006) • The Unforeseen (2007)Categories:- 1978 films

- American films

- English-language films

- American drama films

- 1970s drama films

- Romantic drama films

- United States National Film Registry films

- Films directed by Terrence Malick

- Films whose cinematographer won the Best Cinematography Academy Award

- Paramount Pictures films

- Films set in Texas

- Films set in 1916

- Films shot in Alberta

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.