- Cistercian architecture

-

The "architecture of light" of Acey Abbey represents the pure style of Cistercian architecture, intended for the utilitarian purposes of liturgical celebration.

The "architecture of light" of Acey Abbey represents the pure style of Cistercian architecture, intended for the utilitarian purposes of liturgical celebration.

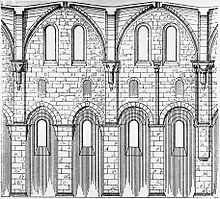

Cistercian architecture is a style of architecture associated with the churches, monasteries and abbeys of the Roman Catholic Cistercian Order. It was headed by Abbot Bernard of Clairvaux (d. 1154), who believed that churches should avoid superfluous ornamentation so as not to distract from the religious life. Cistercian architecture was simple and utilitarian, and though images of religious subjects were allowed in very limited instances (such as the crucifix), many of the more elaborate figures that commonly adorned medieval churches were not; their capacity for distracting monks was criticised in a famous letter by Bernard.[1] Early Cistercian architecture shows a transition between Romanesque and Gothic architecture. Later abbeys were also constructed in Renaissance and Baroque styles, though by then simplicity is rather less evident.

In terms of construction, buildings were made where possible of smooth, pale, stone. Columns, pillars and windows fell at the same base level, and if plastering was done at all, it was kept extremely simple. The sanctuary kept a simple style of proportion of 1:2 at both elevation and floor levels. To maintain the appearance of ecclesiastical buildings, Cistercian sites were constructed in a pure, rational style; and may be counted among the most beautiful relics of the Middle Ages.[2]

Most Cistercian abbeys and churches were built in remote valleys far from cities and populated areas, and this isolation and need for self-sustainability bred an innovativeness among the Cistercians. Many Cistercian establishments display early examples of hydraulic engineering and waterwheels. After stone, the two most important building materials were wood and metal. The Cistercians were careful in the management and conservation of their forests; they were also skilled metallurgists, and their skill with metal has been associated directly with the development of Cistercian architecture, and the spread of Gothic architecture as a whole.

Contents

Theological principles

In the mid-12th century, one of the leading churchmen of his day, the Benedictine Abbot Suger of Saint-Denis, united elements of Norman architecture with elements of Burgundian architecture (rib vaults and pointed arches respectively), creating the new style of Gothic architecture.[3] This new "architecture of light" was intended to raise the observer "from the material to the immaterial"[4] — it was, according to the 20th century French historian Georges Duby, a "monument of applied theology".[5] St Bernard saw much of church decoration as a distraction from piety,[6] and in one of his letters he condemned the more vigorous forms of early 12th century decoration:[7]

But in the cloister, in the sight of the reading monks, what is the point of such ridiculous monstrosity, the strange kind of shapely shapelessness? Why these unsightly monkeys, why these fierce lions, why the monstrous centaurs, why semi-humans, why spotted tigers, why fighting soldiers, why trumpeting huntsmen? …In short there is such a variety and such a diversity of strange shapes everywhere that we may prefer to read the marbles rather than the books.[7]

These sentiments were repeated frequently throughout the Middle Ages,[7] and the builders of the Cistercian monasteries had to adopt a style that observed the numerous rules inspired by Bernard's austere aesthetics.[6] However, the order itself was receptive to the technical improvements of Gothic principles of construction and played an important role in its spread across Europe.[6]

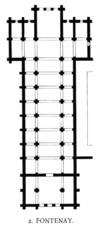

This new Cistercian architecture embodied the ideals of the order, and was in theory at least utilitarian and without superfluous ornament.[8] The same "rational, integrated scheme" was used across Europe to meet the largely homogeneous needs of the order.[8] Various buildings, including the chapter-house to the east and the dormitories above, were grouped around a cloister, and were sometimes linked to the transept of the church itself by a night stair.[8] Usually Cistercian churches were cruciform, with a short presbytery to meet the liturgical needs of the brethren, small chapels in the transepts for private prayer, and an aisled nave that was divided roughly in the middle by a screen to separate the monks from the lay brothers.[9]

The mother house of the order, Cîteaux Abbey, had in fact developed the most advanced style of painting, at least in illuminated manuscripts, during the first decades of the 12th century, playing an important part in the development of the image of the Tree of Jesse. However, as Bernard of Clairvaux, strongly hostile to imagery, increased in influence in the order, painting ceased, and was finally banned altogether in the order, probably from the revised rules approved in 1154. Crucifixes were allowed, and later some painting and decoration crept back in.[10]

Construction

The building projects of the Church in the High Middle Ages showed an ambition for the colossal, with vast amounts of stone being quarried, and the same was true of the Cistercian projects.[11] Foigny Abbey was 98 metres (322 ft) long, and Vaucelles Abbey was 132 metres (433 ft) long.[11] Monastic buildings came to be constructed entirely of stone, right down to the most humble of buildings. In the 12th and 13th centuries, Cistercian barns consisted of a stone exterior, divided into nave and aisles either by wooden posts or by stone piers.[12]

The Cistercians acquired a reputation in the difficult task of administering the building sites for abbeys and cathedrals.[13] St Bernard's own brother, Achard, is known to have supervised the construction of many abbeys, such as Himmerod Abbey in the Rhineland.[13] Others were Raoul at Saint-Jouin-de-Marnes, who later became abbot there; Geoffrey d'Aignay, sent to Fountains Abbey in 1133; and Robert, sent to Mellifont Abbey in 1142.[13] On one occasion the Abbot of La Trinité at Vendôme loaned a monk named John to the Bishop of Le Mans, Hildebert de Lavardin, for the building of a cathedral; after the project was completed, John refused to return to his monastery.[13]

The Cistercians "made it a point of honour to recruit the best stonecutters", and as early as 1133, St Bernard was hiring workers to help the monks erect new buildings at Clairvaux.[14] It is from the 12th century Byland Abbey in Yorkshire that the oldest recorded example of architectural tracing is found.[15] Tracings were architectural drawings incised and painted in stone, to a depth of 2-3 mm, showing architectural detail to scale.[15] The first tracing in Byland illustrates a west rose window, while the second depicts the central part of that same window.[15] Later, an illustration from the latter half of the 16th century would show monks working alongside other craftsmen in the construction of Schönau Abbey.[14]

Engineering

The Cistercian order was innovative in developing techniques of hydraulic engineering for monasteries established in remote valleys.[6] In Spain, one of the earliest surviving Cistercian houses, the Real Monasterio de Nuestra Senora de Rueda in Aragon, is a good example of such early hydraulic engineering, using a large waterwheel for power and an elaborate water circulation system for central heating. Much of this practicality in Cistercian architecture, and indeed in the construction itself, was made possible by the order's own technological inventiveness. The Cistercians are known to have been skilled metallurgists,[16] and as the historian Alain Erlande-Brandenburg writes:

The quality of Cistercian architecture from the 1120s onwards is related directly to the Order's technological inventiveness. They placed importance on metal, both the extraction of the ore and its subsequent processing. At the abbey of Fontenay the forge is not outside, as one might expect, but inside the monastic enclosure: metalworking was thus part of the activity of the monks and not of the lay brothers. … It is probable that this experiment spread rapidly; Gothic architecture cannot be understood otherwise.[17]

Much of the progress of architecture depended on the mastery of metal, from its extraction to the cutting of the stone, especially in relation to the quality of the metal tools used in construction.[18] Metal was also used extensively by Gothic architects from the 12th century on, in tie rods across arches and later in the reinforced stone of the Rayonnant style.[19] The other building material, wood, was in short supply after the drastic deforestation of the 10th and 11th centuries.[20] The Cistercians acted with particular care in the careful management and conservation of their forests.[21]

Legacy

The Cistercian abbeys of Fontenay in France,[22] Fountains in England,[23] Alcobaça in Portugal,[24] Poblet in Spain[25] and Maulbronn in Germany are today recognised as UNESCO World Heritage Sites.[26]

The abbeys of France and England are fine examples of Romanesque and Gothic architecture. The architecture of Fontenay has been described as "an excellent illustration of the ideal of self-sufficiency" practised by the earliest Cistercian communities.[22] The abbeys of 12th century England were stark and undecorated – a dramatic contrast with the elaborate churches of the wealthier Benedictine houses – yet to quote Warren Hollister, "even now the simple beauty of Cistercian ruins such as Fountains and Rievaulx, set in the wilderness of Yorkshire, is deeply moving".[27]

In the purity of architectural style, the beauty of materials and the care with which the Alcobaça Monastery was built,[24] Portugal possesses one of the most outstanding and best preserved examples of Early Gothic.[28] Poblet Monastery, one of the largest in Spain, is considered similarly impressive for its austerity, majesty, and the fortified royal residence within.[25]

The fortified Maulbronn Abbey in Germany is considered "the most complete and best-preserved medieval monastic complex north of the Alps".[26] The Transitional Gothic style of its church had a major influence in the spread of Gothic architecture over much of northern and central Europe, and the abbey's elaborate network of drains, irrigation canals and reservoirs has since been recognised as having "exceptional" cultural interest.[26]

In Poland, the former Cistercian monastery of Pelplin Cathedral is an important example of Brick Gothic. Wąchock abbey is one of the most valuable examples of Polish Romanesque architecture. The largest Cistercian complex, the Abbatia Lubensis (Lubiąż, Poland), is a masterpiece of baroque architecture and the second largest Christian architectural complex in the world.

See also

Notes

- ^ Bernard's letter

- ^ "Cistercians in the British Isles". Catholic Encyclopedia. NewAdvent.org. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/16025b.htm. Retrieved 2009-04-03.

- ^ Toman, p 8-9

- ^ Toman, p 9

- ^ Toman, p 14

- ^ a b c d Toman, p 10

- ^ a b c Harpham, p 39"

- ^ a b c Lalor, p 1

- ^ Lalor, p 1, 38

- ^ Dodwell, 211-214

- ^ a b Erlande-Brandenburg, p 32-34

- ^ Erlande-Brandenburg, p 28

- ^ a b c d Erlande-Brandenburg, p 50

- ^ a b Erlande-Brandenburg, p 101

- ^ a b c Erlande-Brandenburg, p 78

- ^ Woods, p 34-35

- ^ Erlande-Brandenburg, p 116-117

- ^ Erlande-Brandenburg, p 116

- ^ Erlande-Brandenburg, p 117

- ^ Erlande-Brandenburg, p 114

- ^ Erlande-Brandenburg, p 114-115

- ^ a b "Cistercian Abbey of Fontenay (No. 165)". UNESCO World Heritage Sites list. unesco.org. http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/165. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- ^ "Studley Royal Park including the Ruins of Fountains Abbey (No. 372)". UNESCO World Heritage Sites list. unesco.org. http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/372. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- ^ a b "Monastery of Alcobaça (No. 505)". UNESCO World Heritage Sites list. unesco.org. http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/505. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- ^ a b "Poblet Monastery (No. 518)". UNESCO World Heritage Sites list. unesco.org. http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/518. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- ^ a b c "Maulbronn Monastery Complex (No. 546)". UNESCO World Heritage Sites list. unesco.org. http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/546. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- ^ Hollister, p 210

- ^ Toman, p 289

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

References

- Dodwell, C.R.; The Pictorial arts of the West, 800-1200, 1993, Yale UP, ISBN 0-300-06493-4

- Erlande-Brandenburg, Alain (1995). The Cathedral Builders of the Middle Ages. Thames & Hudson Ltd. ISBN 0500300526 ISBN 978-0-500-30052-7.

- Hollister, C. Warren (1966). The Making of England, 55 BC to 1399. Volume I of A History of England, edited by Lacey Baldwin Smith (Sixth Edition, 1992 ed.). Lexington, MA. ISBN 0-669-24457-0.

- Lalor, Brian, ed (2003). The Encyclopedia of Ireland. Gill and Macmillan. ISBN 0-7171-30000-2.

- Toman, Rolf, ed (2007). The Art of Gothic: Architecture, Sculpture, Painting. photography by Achim Bednorz. Tandem Verlag GmbH. ISBN 978-3-8331-4676-3.

- Woods, Thomas, How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization (2005), ISBN 0-89526-038-7.

External links

Categories:- Architectural styles

- Medieval French architecture

- Cistercian Order

- Romanesque architecture

- Gothic architecture

- Christian monastic architecture

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.