- Cheyenne language

-

Cheyenne Tsėhesenėstsestotse Spoken in United States Region Montana and Oklahoma Native speakers 1,721[1] (date missing) Language family Algic- Algonquian

- Cheyenne

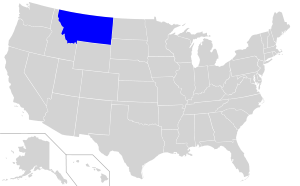

Language codes ISO 639-2 chy ISO 639-3 chy  Cheyenne language spread in the United States.

Cheyenne language spread in the United States.This page contains IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Unicode characters. The Cheyenne language (Tsėhesenėstsestotse or, in easier spelling, Tsisinstsistots) is a Native American language spoken by the Cheyenne people, predominantly in present-day Montana and Oklahoma in the United States. It is part of the Algonquian language family. Like all Algonquian languages, it has complex agglutinative morphology.

Contents

Classification

Cheyenne is one of the Algonquian languages, which is a subphylum of the Algic languages. Specifically, it is a Plains Algonquian language. However, Plains Algonquian, which also includes Arapaho and Blackfoot, is an areal rather than genetic subgrouping.

Geographic distribution

Cheyenne is spoken on the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation in Montana and in Oklahoma. It is spoken by about 1,000 people, all adults.

Phonology

Cheyenne phonology is quite simple. While there are only three basic vowels, they can be pronounced in three ways: high pitch (e.g. á), low pitch (e.g. a), and voiceless (e.g. ė).[2] The high and low pitches are phonemic, while vowel devoicing is governed by environmental rules, making voiceless vowels allophones of the voiced vowels. The phoneme /h/ is realized as [s] in the environment between /e/ and /t/ (h > s / e _ t). /h/ can also be realized as [ʃ] between [e] and [k] (h > ʃ / e _ k) i.e. /nahtóna/ nȧhtǒna alien, /nehtóna/ nėhtǒna your daughter. The digraph ‘ts’ represents assibilated /t/; a phonological rule of Cheyenne is that underlying /t/ becomes affricated before an /e/ (t > ts/_e). Therefore, ‘ts’ is not a separate phoneme, but an allophone of /t/. The sound [x] is not a phoneme, but derives from other phonemes, including /ʃ/ (when /ʃ/ precedes or follows a non-front vowel, /a/ or /o/), and the far-past tense morpheme /h/ which is pronounced [x] when it precedes a morpheme which starts with /h/.

The Cheyenne orthography of 14 letters is neither a pure phonemic system nor a phonetic transcription; it is, in the words of linguist Wayne Leman, a "pronunciation orthography". In other words, it is a practical spelling system designed to facilitate proper pronunciation. Some allophonic variants, such as voiceless vowels, are shown. <e> represents not the phoneme /e/, but is usually pronounced as a phonetic [ɪ] and sometimes varies to [ɛ]. <š> represents /ʃ/.

Consonants Bilabial Dental Postalveolar Velar Glottal Stop p t k ʔ Fricative v s ʃ (x) h Nasal m n Vowels Front Central Back Non-low e o Low a Voicing

Cheyenne has 14 distinct phonemic sounds, several of which can be devoiced. Devoicing naturally occurs in the last vowel of a word or phrase. It can also occur in vowels at the penultimate and prepenultimate positions within a word. Non-high [a] and [o] can also become at least partially devoiced. The [h] can be absorbed by a voiceless vowel. Examples are given below

Penultimate Devoicing

/hohkox/ hȯhkoxe ‘Ax'; /tétahpetát/ tsetȧhpetȧtse ‘the one who is big’; /mótehk/ mǒtʃėʃke ‘knife’

Devoicing occurs when certain vowels directly precede the consonants [t], [s], [ʃ], [k], or [x] that is itself followed by followed by an [e]. This rule is linked to the rule of e-Epenthesis. Which simply states that [e] appears in the environment of a consonant and a word boundary. [3]

Prepenultimate Devoicing

/tahpeno/ tȧpeno ‘flute’; /kosáné/ kȯsâne sheep (pl.)’; /mahnohtehtovot/ mȧhnȯhtsėstovȯtse ‘if you ask him’

A vowel that does not have a high pitch is devoiced if it is followed by a voiceless fricative and not preceded by [h]. [4]

Special [a] and [o] Devoicing

/émóheeohtéo/ émôheeȯhtseo’o ‘they are gathering’; /náohkeho’sóe/ náȯhkėho’soo’e ‘I regularly dance’; /nápóahtenáhnó/ nápôȧhtsenáhno ‘I punched him in the mouth’

Non-high [a] and [o] become at least partially devoiced when they are preceded by a voiced vowel and followed by an [h], a consonant and two or more syllables. [5]

Consonant Devoicing

émane [ímaṅi] ‘it is yellow’

When preceding a voiceless segment a consonant is devoiced. [6]

h-Absorbtion

pėhévoestomo’he ‘’kind’’ + tse ‘imperative suffix’ > pėhévoestomo’ėstse tsé- ‘conjunct prefix’ + ena’he ‘old’ + tse ‘3rd pers. Suffix > tséena’ėstse ‘ the one who is old’ né + ‘you’ + -one’xȧho’he ‘burn’ + tse ‘suffix for some ‘you-me’ transitive animate forms’ > néone’xȧho’ėstse ‘ you burn me’

The [h] is absorbed when preceded or followed by voiceless vowels. [7]

Pitch

There are several rules that govern pitch use in Cheyenne. Pitch can be ˊ = high, ˋ = low, ˉ = mid, ˇ = hanging low and ˆ = raised high.

High-Raising

/ʃé?ʃé/ ʃê?ʃe ‘duck’; /sémón/ sêmo ‘boat’

A high pitch becomes a raised high when it is not followed by another high vowel and precedes an underlying word-final high. [8]

Low-to-High Raising

/máʃèné/ méʃéne ‘ticks’; /návóòmó/ návóómo ‘I see him’; /póèsó/ póéso ‘cat’

A low vowel is raised to the high position when it precedes a high and is followed by a word final high. [9]

Low-to-Mid Raising

/kòsán/ kōsa ‘sheep (sg.)’; /kè?é/ kē?e ‘woman’; /éhòmòsé/ éhomōse ‘he is cooking’

A low vowel becomes a mid when it is followed by a word-final high but not directly followed by a high vowel.[10]

High Push-Over

/néháóónámà/ néhâòònàma ‘we (incl) prayed’; /néméhó?tónè/ némêhò?tòne ‘we (incl) love him’; /náméhósànémé/ námêhòsànême ‘we (excl) love’

A high vowel becomes low if it comes before a high and followed by a phonetic low. [11]

Word-Medial High-Raising

/émésèhe/ émêsehe ‘he is eating’; /téhnémènétó/ tséhnêmenéto ‘when I sang’; /násáàmétòhénòtò/ /nádâamétȯhênoto ‘I didn’t give him to him’

According to Leman, "some verbal prefixes and preverbs go through the process of World-Medal High-Raising. A high is raised if it follows a high (which is not a trigger for the High Push-Over rule) and precedes a phonetic low. One or more voiceless syllables may come between the two highs. (A devoiced vowel in this process must be underlyingly low, not an underlyingly high vowel which has been devoiced by the High-Pitch Devoicing rule.)” [12]

Grammar

Cheyenne represents the participants of an expression not as separate pronoun words but as affixes on the verb. Its pronominal system uses typical Algonquian distinctions: three grammatical persons (1st, 2nd, 3rd) plus obviated 3rd (3', also known as 4th person[13]), two numbers (singular, plural), animacy (animate and inanimate) and inclusivity and exclusivity on the first person plural. The 3' (obviative) person is an elaboration of the third; it is an "out of focus" third person. When there are two or more third persons in an expression, one of them will become obviated. If the obviated entity is an animate noun, it will be marked with an obviative suffix, typically -o or -óho. Verbs register the presence of obviated participants whether or not they are present as nouns.

Pronominal affixes

There are three basic pronominal prefixes in Cheyenne:

ná- First person

né- Second person

é- Third personThese three basic prefixes can be combined with various suffixes to express all of Cheyenne's pronominal distinctions. For example, the prefix ná- can be combined on a verb with the suffix -me to express the first person plural exclusive ("we, not including you"), as with nátahpetame, "we.EXCL are big."

Historical development

Like all the Algonquian languages, Cheyenne developed from a reconstructed ancestor referred to as Proto-Algonquian (often abbreviated "PA"). The sound changes on the road from PA to modern Cheyenne are complex, as exhibited by the development of the PA word *erenyiwa "man" into Cheyenne hetane:

- First, the PA suffix -wa drops (*erenyi)

- The geminate vowel sequence -yi- simplifies to /i/ (semivowels were phonemically vowels in PA; when PA */i/ or */o/ appeared before another vowel, it became non-syllabic) (*ereni)

- PA */r/ changes to /t/ (*eteni)

- /h/ is added before word-initial vowels (*heteni)

- Due to a vowel chain-shift, the vowels in the word wind up as /e/, /a/ and /e/ (PA */e/ sometimes corresponds to Cheyenne /e/ and sometimes to Cheyenne /a/; PA */i/ almost always corresponds to Cheyenne /e/, however) (hetane).

Lexicon

Some Cheyenne words (with the Proto-Algonquian reconstructions where known):

- ame (PA *pemyi, "grease")

- he'e (PA *weθkweni, "his liver")

- hē'e (PA **eθkwe·wa, "woman")

- hetane (PA *erenyiwa, "man")

- ma'heo'o ("sacred spirit, God")

- matana (PA *meθenyi, "milk")

Translations

Early work was done on the Cheyenne language by Rodolphe Charles Petter, a Mennonite missionary based in Lame Deer, Montana from 1916.[14]

Notes

- ^ Indigenous Languages Spoken in the United States

- ^ There are also two other variants of the phonemic pitches: the mid (e.g. ā) and raised-high pitches (e.g. ô). These are often not represented in writing, although there are standard diacritics to indicate all of them. Linguist Wayne Leman included one more variant in his International Journal of American Linguistics[1] (1981) article on Cheyenne pitch rules, a lowered-high pitch (e.g. à), but has since recognized that this posited pitch is the same as a low pitch.

- ^ Leman, 1979, Cheyenne Grammar Notes p. 215

- ^ Leman, 1979, Cheyenne Grammar Notes p. 215

- ^ Leman, 1979, Cheyenne Grammar Notes p. 218

- ^ Leman, 1979, Cheyenne Grammar Notes p. 218

- ^ Leman, 1979, Cheyenne Grammar Notes p. 217

- ^ Leman, 1979, Cheyenne Grammar Notes p. 219

- ^ Leman, 1979, Cheyenne Grammar Notes p. 219

- ^ Leman, 1979, Cheyenne Grammar Notes p. 219

- ^ Leman, 1979, Cheyenne Grammar Notes p. 219

- ^ Leman, 1979, Cheyenne Grammar Notes p. 220

- ^ http://books.google.com/books?id=Oe70t90kk3oC&pg=PA62&lpg=PA62

- ^ "Petter, Rodolphe Charles (1865-1947)" Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online, accessed September 20, 2009

References

- Wayne Leman, 1980. A Reference Grammar of the Cheyenne Language. University of Colorado Press. (out-of-print; republished: http://webspace.webring.com/people/cc/cheyenne_language/orderform.doc)

- Marianne Mithun, 1999. The Languages of Native North America. Cambridge Language Surveys. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Leman, Wayne. Cheyenne Grammar Notes Volume 2. Greeley, Colorado: University of Colorado Press, 1979.

External links

Languages of OklahomaItalics indicate extinct languages

Languages of OklahomaItalics indicate extinct languagesAlabama · Arapaho · Caddo · Cayuga · Cherokee · Cheyenne · Chickasaw · Chiwere (Iowa and Otoe) · Choctaw · Comanche · Delaware · English · Hitchiti-Mikasuki · Kansa · Koasati · Mescalero-Chiricahua Apache · Mesquakie (Fox, Kickapoo, and Sauk) · Muscogee · Osage · Ottawa · Pawnee · Plains Apache · Ponca · Potawatomi · Quapaw · Seneca · Shawnee · Spanish · Tonkawa · Vietnamese · Wichita · Wyandot · Yuchi

5

Categories:- Language articles with undated speaker data

- Agglutinative languages

- Cheyenne tribe

- Plains Algonquian languages

- Languages of the United States

- Indigenous languages of the North American Plains

- Indigenous languages of the Americas

- Algonquian

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.