- Merseburg Incantations

-

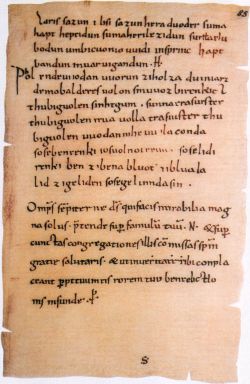

The Merseburg Incantations (German: die Merseburger Zaubersprüche) are two medieval magic spells, charms or incantations, written in Old High German. They are the only known examples of Germanic pagan belief preserved in this language. They were discovered in 1841 by Georg Waitz,[1] who found them in a theological manuscript from Fulda, written in the 9th or 10th century,[2] although there remains some speculation about the date of the charms themselves. The manuscript (Cod. 136 f. 85a) was stored in the library of the cathedral chapter of Merseburg, hence the name.

Contents

History

Among the early Germanic peoples, incantations (Old Norse galdr) had the function "of rendering usable, through binding words, the magic powers which people wished to make serve them"[3] They have survived in large numbers, particularly from the area of the Germanic languages. However, they all date from the Middle Ages and therefore bear the stamp or show the influence of Christianity. What is unique about the Merseburg Incantations is that they still reflect very clearly their pre-Christian origin (from before the year 750).[4][5] They were written down for an unknown reason in the 10th century by a literate cleric, possibly in the abbey of Fulda, on a blank page of a liturgical book, which later passed to the library at Merseburg. The incantations have thus been transmitted in Caroline minuscule on the flyleaf of a Latin sacramentary.

The spells became famous in modern times through the appreciation of the Grimm brothers, who wrote as follows:

- Lying between Leipzig, Halle and Jena, the extensive library of the Cathedral Chapter of Merseburg has often been visited and made use of by scholars. All have passed over a codex which, if they chanced to take it up, appeared to offer only well-known church items, but which now, valued according to its entire content, offers a treasure such that the most famous libraries have nothing to compare with it...

The spells were published later by the Brothers Grimm in On two newly-discovered poems from the German Heroic Period (1842).

The manuscript of the Merseburg Incantations was on display until November 2004 as part of the exhibition "Between Cathedral and World - 1000 years of the Chapter of Merseburg", at Merseburg cathedral. They were previously exhibited in 1939.[citation needed]

Incantations

Each charm is divided into two parts: a preamble telling the story of a mythological event; and the actual spell in the form of a magic analogy (just as it was before... so shall it also be now...). In their verse form, the spells are of a transitional type; the lines show not only traditional alliteration but also the end-rhymes introduced in the Christian verse of the 9th century.

1. Liberation of prisoners

The first spell is a "Lösesegen" (blessing of release), describing how a number of "Idisen"[2] free from their shackles warriors caught during battle. The last two lines contain the magic words "Leap forth from the fetters, escape from the foes" that are intended to release the warriors.

Eiris sazun idisi

sazun hera duoder.

suma hapt heptidun,

suma heri lezidun,

suma clubodun

umbi cuoniouuidi:

insprinc haptbandun,

inuar uigandun.Once sat women,

They sat here, then there.

Some fastened bonds,

Some impeded an army,

Some unraveled fetters:

Escape the bonds,

flee the enemy![1]2. Horse cure

A Scandinavian C-bracteate (Seeland-II-C, from AD 500) often viewed as a depiction of Odin healing his horse.[6]

A Scandinavian C-bracteate (Seeland-II-C, from AD 500) often viewed as a depiction of Odin healing his horse.[6]Phol is with Wodan when Baldur's horse dislocates its foot while riding through the forest (holza). Wodan is saying as a result: "Bone to bone, blood to blood, limb to limb, as if they were glued".

Figures that can be clearly identified within Continental Germanic mythology are "Uuôdan" (Wodan) and "Frîia" (Frija). Depictions found on Migration Period Germanic bracteates are often viewed as Wodan (Odin) healing a horse.[6]

Comparing Norse mythology, Wodan is well-attested as the cognate of Odin. Frija the cognate of Frigg,[6] also identified with Freyja.[7] Balder is apparently Norse Baldr. Phol is apparently the masculine form of Uolla, but the context makes clear that it is another name of Balder.[2] Uolla has been linked to Fulla, a minor goddess and a handmaid of Frigg.[6] Sunna (the Sun) in Norse mythology is Sól, though her sister Sinthgunt is otherwise unattested.[8]

Phol ende uuodan uuorun zi holza.

du uuart demo balderes uolon sin uuoz birenkit.

thu biguol en sinthgunt, sunna era suister;

thu biguol en friia, uolla era suister;

thu biguol en uuodan, so he uuola conda:sose benrenki, sose bluotrenki,

sose lidirenki:

ben zi bena, bluot zi bluoda,

lid zi geliden, sose gelimida sin.Phol and Wodan were riding to the woods,

and the foot of Balder's foal was sprained

So Sinthgunt, Sunna's sister, conjured it.

and Frija, Volla's sister, conjured it.

and Wodan conjured it, as well he could:Like bone-sprain, so blood-sprain,

so joint-sprain:

Bone to bone, blood to blood,

joints to joints, so may they be glued.[9]Similar charms in Norwegian folklore

Two "horse cure" incantations strikingly similar to the Merseburg incantation are recorded in 19th and 20th century Norway. In the 19th century charm, the invocation is to Jesus, whereas the 20th century charm invokes the 11th century Norwegian king Olaf II of Norway. The 20th century spell was collected in Møre, Norway, where it was presented as for use in healing a bone fracture. The charms read:

19th century charm:

- Jesus himself rode to the heath,

- And as he rode, his horse's bone was broken.

- Jesus dismounted and healed that:

- Jesus laid marrow to marrow,

- Bone to bone, flesh to flesh.

- Jesus thereafter laid a leaf

- So that these should stay in their place.[10]

20th century charm:

- Saint olav rode in

- green wood;

- broke his little

- horse's foot.

- Bone to bone,

- flesh to flesh,

- skin to skin.

- In the name of God,

- amen.[11]

Adaptations

Many German rock groups and musicians have been inspired by the Merseburg Incantations and produced their own settings. The already "classic" adaptation of the first incantation comes from the group Ougenweide; it is a free invention based on no real musical tradition. The group In Extremo, whose song "Küss mich" ("Kiss me") was in the 2003 charts, included a version of the first incantation in their album Verehrt und angespien (Adored and spat at) in 1999 and of the second in their album Sünder ohne Zügel (Sinners without reins) in 2001. Also in that year the project Helium Vola did the same in a quite different context. The band Corvus Corax features both charms in a single song on the album Ante Casu Peccati (Before the Fall). Yet another adaptation was featured by Tanzwut, a musical project of Corvus Corax, in the album of the same title. A further band, Nagelfar, has included the incantations on Die Sprüche auf Virus West. The group Eirisproject features both charms on their album Germanic Mantra from 2007. There is also an interpretation by Saltatio Mortis from the 2003 album Heptessenz.[12] German group Ignis Fatuu recorded a song "Zauberspruch" on their 2009 album Es Werde Licht.

See also

Notes

- ^ a b Jeep, John. 'Medieval Germany: An Encyclopedia'. Routledge; 2001. PP112-113. ISBN 0-8240-7644-3

- ^ a b c Calvin, Thomas. 'An Anthology of German Literature', D. C. Heath & co. ASIN: B0008BTK3E,B00089RS3K. P5-6.

- ^ Simek, Rudolf. 'Lexikon der germanischen Mythologie'. A. Kröner, 1995. ISBN 3-520-36802-1

- ^ Priest, George Madison. 'A Brief History of German Literature'. Charles Scribner's Sons, 1909. P.11. ASIN: B0008AOAGC

- ^ Todd, Henry & Weeks, Raymond, Editors,'Romanic Review Quarterly Journal, Volume VII, P.123. Columbia University Press, 1916.

- ^ a b c d Lindow, John. Norse Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs (2001) Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-515382-0.

- ^ Jeep's translation gives "Freya". Benjamin Thorpe (Northern Mythology, 1851, p. 23) actually read the manuscript as having Frua rather than Friia, Frua being the cognate of Norse Freyja.

- ^ Bostock, John Knight. (1976) A Handbook on Old High German Literature, page 32. Oxford University Press ISBN 0198153929

- ^ translation from Benjamin W. Fortson, Indo-European language and culture: an introduction, Wiley-Blackwell, 2004, ISBN 9781405103169, p. 325. The reading of the original text is given both by Jeeps (2001) and (indicating vowel length) by Fortson (2004).

- ^ Griffiths (2006:174).

- ^ Kvideland, Sehmsdorf (2010:141).

- ^ Dettenberger, Michael (2003). "Saltatio Mortis – Heptessenz" (in German). Sonic Seducer (4). http://www.sonic-seducer.de/index.php/component/option,com_reviews/anzeige,3547/func,detail/.

References

- Griffiths, Bill (2006). Aspects of Anglo-Saxon Magic. Anglo-Saxon Books. ISBN 1-898281-33-5

- Kvideland, Reimund. Sehmsdorf, Henning K. (editors) (2010). Scandinavian Folk Belief and Legend. University of Minnesota Press.

Dísir (North Germanic) and Idisi (West Germanic) Dísir Idisi See also Norns · Valkyrie · Fylgja · Matres and Matrones · Sigewif · Elf · Female spirits in Germanic paganismCategories:- Germanic mythology

- Germanic paganism

- Merseburg

- Old High German literature

- Sources on Germanic paganism

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.