- New Romanticism

-

New Romanticism (also referred to as blitz kids and by a wide variety of other names),[1] was a youth fashion and music movement in the United Kingdom that flourished roughly between the years 1979 and 1984 — peaking around 1981. Developing in London nightclubs such as Billy's and The Blitz and spreading to other major cities in the UK, it was associated with bands including Ultravox, Visage, Duran Duran, Spandau Ballet, ABC and Culture Club. Also labelled as New Romantic, although they had no direct connection to the original scene, were Adam and the Ants and Bow Wow Wow.[1] A number of these bands adopted synthesizers and helped to develop synthpop in the early 1980s, which, combined with the distinctive New Romantic visuals helped them first to national success in the UK and, with help of MTV to play a major part in the Second British Invasion of the US charts. By the mid-1980s the original movement had largely dissipated and, although some of the artists associated with the scene continued their careers, they had largely abandoned the aesthetics of the movement and the synthpop sound. There were attempts to revive the movement from the 1990s, including the short-lived romo movement.

Contents

Characteristics

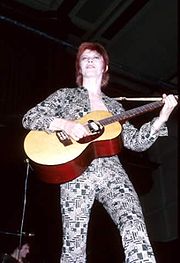

David Bowie's androgynous Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders look, which was a major influence on the movement

David Bowie's androgynous Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders look, which was a major influence on the movement

New Romanticism can be seen as a reaction to punk,[2] and a revival of the glam rock of the early 1970s, particularly that of David Bowie and Roxy Music.[3] In terms of style it rejected the austerity and anti-fashion stance of punk.[4] Both sexes often dressed in counter-sexual or androgynous clothing and wore cosmetics such as eyeliner and lipstick, partly derived from earlier punk fashions.[5] This "gender bending" was particularly evident in figures such as Boy George of Culture Club and Marilyn (Peter Robinson).[2] Fashion was based on varied looks based on romantic themes, including frilly fop shirts in the style of the English Romantic period,[5] Russian constructivism, Bonny Prince Charlie, French Incroyables and 1930s Cabaret, Hollywood starlets, Puritans and clowns, with any look being possible if it was adapted to be unusual and striking.[6] Common hairstyles included quiffs,[6] mullets and wedges.[2] Soon after they began to gain mainstream attention, however, many New Romantic bands dropped the eclectic clothes and makeup in favour of sharp suits that echoed Bowie's Thin White Duke image.[7]

New Romantic looks were adopted and adapted by major fashion designers, began to influence major collections and were spread, with a delay, through reviews of what was being worn in clubs via magazines including i-D and The Face.[6] The emergence of the New Romantic movement into the mainstream coincided with Vivienne Westwood's unveiling of her "pirate collection", which was promoted by Bow Wow Wow and Adam and the Ants, who were managed by her then partner Malcolm McLaren.[8]

While some contemporary bands, particularly those of the 2 Tone ska revival, dealt with issues of unemployment and urban decay, New Romantics adopted an escapist and aspirational stance.[9] With its interest in design, marketing and image, has been seen an acceptance of Thatcherism and style commentator Peter Yorke even suggested that it was aligned with the New Right.[10]

Names

In its early stages the movement was known by a large number of names, including "new dandies", "romantic rebels", "peacock punk", "the futurists", "the cult with no name" and eventually as the "Blitz kids". As the scene moved beyond a single club the press settled on the name New Romantics.[1][11]

History

Origins

The movement developed out of David Bowie and Roxy Music nights run in the nightclub Billy's in Dean Street, London.[12] In 1979, the growing popularity of the club forced organisers Steve Strange and Rusty Egan to relocate to a larger venue in the Blitz, a wine bar in Great Queen Street, Covent Garden, where they ran a Tuesday night "Club for Heroes".[13] Its patrons dressing as uniquely as they could in an attempt to draw the most attention.[13] Strange worked as the doorman and Egan was the club's DJ. The Blitz club became known for its exclusive door policy and strict dress code. Strange would frequently deny potential patrons admittance because he felt that they were not costumed creatively or subversively enough to blend in well with those inside the club. In a highly publicised incident, Mick Jagger tried to enter the club while under the influence of alcohol, but was denied entry by Strange.[14] The club spawned several spin-offs and there were soon clubs elsewhere in London and in other major British cities, including London, Manchester, Liverpool and Birmingham.[3]

While still at Billy's, Strange and Egan joined Billy Currie and Midge Ure of Ultravox to form the band Visage. Before forming Culture Club, Boy George and Marilyn worked as cloakroom attendants at the Blitz.[15] The video for David Bowie's 1980 UK number one single "Ashes to Ashes" included appearances by Strange with three other Blitz kids, the first time that mainstream audiences were aware of a glam rock revival.[3]

Styles of music

Main article: Synthpop David Sylvian (right) of Japan onstage in 1979, wearing the poet shirt common in the early look of the movement

David Sylvian (right) of Japan onstage in 1979, wearing the poet shirt common in the early look of the movement

Bands that emerged from the New Romantic movement became closely associated with the use of synthesizers to create rock and pop music. This synthpop was prefigured in the 1960s and early 1970s by the use of synthesizers in progressive rock, electronic art rock, disco and particularly the "Kraut rock" of bands like Kraftwerk and the three albums made by Bowie with Brian Eno in his "Berlin period". After the breakthrough of Tubeway Army and Gary Numan in the British Singles Chart in 1979, large numbers of artists began to enjoy success with a synthesizer-based sound and they came to dominate the pop music of the early 1980s. Key New Romantic bands that adopted synthpop included Duran Duran, Japan, Ultravox, Visage, Spandau Ballet and ABC.[16]

Early synthpop has been described as "eerie, sterile, and vaguely menacing", using droning electronics with little change in inflection. Later the introduction of dance beats made the music warmer and catchier and contained within the conventions of three-minute pop.[17] Duran Duran, who emerged from the Birmingham scene, have been credited with incorporating a disco-derived rhythm section into synthpop to produce a catchier and warmer sound, which provided them with a series of hit singles.[17] They would soon be followed onto the British charts by a series of bands utilising synthesisers to create catchy three-minute pop songs.[18] Synthpop reached its commercial peak in the UK in the winter of 1981-2, with bands including Japan, Ultravox and Depeche Mode enjoying top ten hits.[16]

Of groups associated with the New Romantic movement, Culture Club avoided a total reliance on synthesizers, producing a sound that combined elements of Motown, the Philly sound and lovers rock.[19] Other London groups, including Bow Wow Wow and Adam and the Ants, utilised the African influenced rhythms of the "Burundi beat".[20]

The second British invasion

Main article: Second British Invasion Duran Duran still sporting their smart suit look in 2009

Duran Duran still sporting their smart suit look in 2009

In the US the cable music channel MTV reached the media capitals of New York City and Los Angeles in 1982.[18][21] Style conscious New Romantic synthpop acts became a major staple of MTV programming. "I Ran (So Far Away)" (1982), by A Flock of Seagulls, is generally considered the first hit by a British act to enter the Billboard Top Ten as a result of the power of video. They would be followed by a large number of acts, many of them employing synthpop sounds, over the next three years, with Duran Duran's glossy videos symbolising the power of MTV and this Second British Invasion. The switch to a "New Music" format in US radio stations was also significant in the success of British bands.[21]

During 1983, 30% of the record sales were from British acts. On 18 July, 18 of the top 40, and 6 of the top 10 singles, were by British artists.[21] Newsweek magazine ran an issue which featured Annie Lennox and Boy George on the cover of one of its issues, with the caption "Britain Rocks America – Again", while Rolling Stone would release an "England Swings" issue with Boy George on the cover.[21] In April 1984, 40 of the top 100 singles, and in a May 1985 survey 8 of the top 10 singles, were by acts of British origin.[22][23]

Decline and revivals

Music journalist Dave Rimmer considered the peak of the movement was the Live Aid concert of July 1985, after which "everyone seemed to take hubristic tumbles",[24] and Simon Reynolds also notes the "Do They Know Its Christmas" single in late 1984 and Live Aid in 1985 as a turning points, with the movement seen as having become decadent, with "overripe arrangements and bloated videos" for songs like Duran Duran's "Wild Boys" and Culture Club's "War Song".[25] The proliferation of acts had led to an anti-synth backlash, with groups including Spandau Ballet, Soft Cell and ABC incorporating more conventional influences and instruments into their sounds.[26] An American reaction against European synthpop and "haircut bands" has been seen as beginning in the mid-1980s with the rise of heartland rock and roots rock.[27] In the UK, the arrival of indie rock bands, particularly The Smiths, has been seen as marking the end of synth-driven New Wave and the beginning of the guitar rock that would come to dominate rock into the 1990s.[28][29] By the end of the 1980s many acts had been dropped by their labels and the solo careers of many New Romantic stars gradually faded.[30]

In the mid-1990s, New Romanticism was the subject of nostalgia-oriented club nights — such as the Human League inspired "Don't You Want Me Baby", and "Planet Earth", a Duran Duran-themed night club whose promoter told The Sunday Times "It's more of a celebration than a revival".[31] In the same period New Romanticism was also an inspiration for the short-lived romo musical movement. It was championed by Melody Maker, who proclaimed on its front cover in 1995 that it was a "future pop explosion" that had "executed" Britpop, and including bands Orlando, Plastic Fantastic, Minty, Viva, Sexus, Hollywood, Dex Dexter. None made the British top 75[32] and after an unsuccessful Melody Maker organised tour most of the bands soon broke up.[33]

See also

- List of New Romantics

Notes

- ^ a b c T. Cateforis, Are We Not New Wave?: Modern Pop at the Turn of the 1980s (University of Michigan Press, 2011), ISBN 0472034707, pp. 47-8.

- ^ a b c S. Borthwick and R. Moy, Popular Music Genres: an Introduction (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004), ISBN 0748617450, p. 132.

- ^ a b c D. Buckley, Strange Fascination: David Bowie, the Definitive Story (London: Random House, 2005), ISBN 0753510022, p. 318.

- ^ R. Evans, Remember the 80s: Now That's What I Call Nostagia! (London: Anova Books, 2009), ISBN 1906032122, p. 16.

- ^ a b D. C. Steer, The 1980s and 1990s (Infobase Publishing, 2009), ISBN 1604133864, p. 37.

- ^ a b c V. Steele, ed., The Berg Companion to Fashion, (London: Berg, 2010), ISBN 1847885926, p. 525.

- ^ R. Till, Pop Cult: Religion and Popular Music (London, Continuum International Publishing Group, 2010), ISBN 0826432360, p. 25.

- ^ R. O'Byrne, Style City: How London Became a Fashion Capital, (London: Frances Lincoln Ltd, 2009), ISBN 0711228957, p. 77.

- ^ Simon Reynolds, Rip It Up and Start Again Postpunk 1978–1984 (London: Faber and Faber, 2005), ISBN 0-571-21570-X, pp. 326 and 410.

- ^ S. Borthwick and R. Moy, Popular Music Genres: an Introduction (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004), ISBN 0748617450, p. 124.

- ^ T. Russell, ed., Encyclopedia of Rock (Crescent Books, 1983), ISBN 0517408651, p. 119.

- ^ "Steve Strange", Showbiz Wales/Southeast Hall of Fame (BBC), August 2009, archived from the original on 29 July 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/60XexInCl.

- ^ a b D. Johnson, "Spandau Ballet, the Blitz kids and the birth of the New Romantics", Observer, 4 October 2009, retrieved 24 July 2011.

- ^ S. Strange, "The most decadent nightclub in the world", Originally from the Mail on Sunday, 10 March 2002, Highbeam Research, retrieved 26 July 2011.

- ^ R. O'Byrne, Style City: How London Became a Fashion Capital, (London: Frances Lincoln Ltd, 2009), ISBN 0711228957, p. 81.

- ^ a b Simon Reynolds, Rip It Up and Start Again Postpunk 1978–1984 (London: Faber and Faber, 2005), ISBN 0-571-21570-X, pp. 334-5.

- ^ a b "Synth pop", Allmusic, archived from the original on 10 March 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/5x6RaN2Dj.

- ^ a b T. Cateforis, The Death of New Wave, archived from the original on 5 August 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/60ik0hkdD.

- ^ Simon Reynolds, Rip It Up and Start Again Postpunk 1978–1984 (London: Faber and Faber, 2005), ISBN 0-571-21570-X, pp. 412-3.

- ^ Simon Reynolds, Rip It Up and Start Again Postpunk 1978–1984 (London: Faber and Faber, 2005), ISBN 0-571-21570-X, pp. 306-7 and 311.

- ^ a b c d Simon Reynolds, Rip It Up and Start Again Postpunk 1978–1984 (London: Faber and Faber, 2005), ISBN 0-571-21570-X, pp. 340 and 342-3.

- ^ "UK acts disappear from US charts". BBC News. 23 April 2002. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/1946331.stm. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ^ Von R. Serge Denisoff and W. L. Schurk, Tarnished Gold: the Record Industry Revisited" (Transaction, 1986), ISBN 0887386180, p. 441.

- ^ D. Rimmer, New Romantics: The Look (London: Omnibus Press, 2003), ISBN 978-0-7119-9396-9, p. 126.

- ^ Simon Reynolds, Rip It Up and Start Again Postpunk 1978–1984 (London: Faber and Faber, 2005), ISBN 0-571-21570-X, p. 517.

- ^ Simon Reynolds, Rip It Up and Start Again Postpunk 1978–1984 (London: Faber and Faber, 2005), ISBN 0-571-21570-X, p. 342.

- ^ Simon Reynolds, Rip It Up and Start Again Postpunk 1978–1984 (London: Faber and Faber, 2005), ISBN 0-571-21570-X, p. 535.

- ^ S. T. Erlewine, "The Smiths", Allmusic, archived from the original on 27 July2011, http://www.webcitation.org/60V6MFojY.

- ^ S. T. Erlewine, "R.E.M.", Allmusic, archived from the original on 27 July 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/60V6bSxZD.

- ^ Simon Reynolds, Rip It Up and Start Again Postpunk 1978–1984 (London: Faber and Faber, 2005), ISBN 0-571-21570-X, p. 523.

- ^ S. Langan, "Worst of times", The Sunday Times 19 Nov 1995; p. 1.

- ^ D. Simpson, "The scenes that time forgot", Guardian.co.uk, 6 August 2009, retrieved 26 July 2011.

- ^ S. T. Erlewine, "Orlando", in V. Bogdanov, C. Woodstra and S. T. Erlewine, eds, All Music Guide to Rock: the Definitive Guide to Rock, Pop, and Soul (Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0-87930-653-X, pp. 828-9.

Further reading

- Peter Childs, Mike Storry (1999). Taylor & Francis. ed. Encyclopedia of Contemporary British Culture. pp. 181–184, 363, 562. ISBN 978-0-415-14726-2. http://books.google.com/books?id=iS4hsxKiMNgC&pg=182#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- Steve Strange (2003). Blitzed! The Autobiography of Steve Strange. Orion. ISBN 978-0-7528-4936-2.

External links

New Wave music Regional scenes Other topics Categories:- Youth culture in the United Kingdom

- Musical subcultures

- Neo-romanticism

- New Wave music

- 1980s fashion

- Theories of aesthetics

- History of fashion

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.