- Incroyables and Merveilleuses

-

The Incroyables (Incredibles) and their female counterparts, the Merveilleuses (Marvelous women, roughly equivalent in this context to "fabulous divas"), were members of a fashionable aristocratic subculture of the Directory period. Whether as catharsis or in a need to reconnect with other survivors of the Reign of Terror, they greeted the new regime with an outbreak of luxury, decadence and even silliness. They held hundreds of balls and started fashion trends in clothing and mannerisms that today might seem exaggerated, affected or even effete. Some for instance preferred to be called "incoyable" or "meveilleuse", thus avoiding the letter R, as in "Révolution." When this period ended, society took a more sober and modest turn.Many Incroyables were "nouveaux riches" who had gained their wealth from selling arms and moneylending. But members of the ruling classes were also among the movement's leading figures and the group heavily influenced the politics, clothing and arts of the period.

Contents

Social Backdrop

Ornate carriages reappeared on the streets of Paris the very next day after the execution of Maximilien de Robespierre brought an end to the Thermidorian Reaction. The Directory period began. There were masters and servants once more in Paris, and the city erupted in a furor of pleasure-seeking and entertainment. Theaters thrived, and popular music satirized the excesses of the Revolution. One popular song of the period called on the French people to "share my horror" and send "these drinkers of human blood" back amongst the monsters from which they had sprung. Its lyrics rejoiced that "your tormentors finally grow pale at the tardy dawn of vengeance."[1]

Many public balls were bals des victimes at which young aristocrats who had lost loved ones to the guillotine danced in mourning dress or wore black armbands, greeting one another with violent movements of the head as if in decapitation. For example, a ball held at the Hôtel Thellusson on the rue de Provence in Paris' tony 9th arrondissement, restricted its guest list to the grown children of the guillotined.[2]

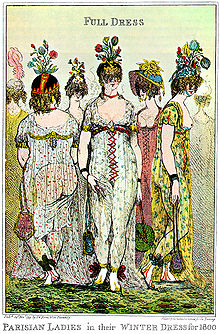

Clothing and Fashions

The Merveilleuses scandalized Paris with dresses and tunics modeled after the ancient Greeks and Romans, cut of light or even transparent linen and gauze. Sometimes so revealing they were termed "woven air", many also displayed cleavage and were too tight to allow pockets. To carry even a handkerchief, these ladies had carry small bags known as reticules. They were fond of wigs, often choosing blonde because the Commune had banned blond wigs, but they also wore them in such colors as black, blue, and green. Enormous hats, short curls like those on Roman busts, and Greek-style sandals were all the rage. These tied above the ankle with crossed ribbons or strings of pearls. Thérésa Tallien became known for wearing expensive rings on the toes of her bare feet and gold circlets on her legs.

The Incroyables, wore eccentric outfits: large earrings, green jackets, wide trousers, huge neckties, thick glasses, and hats topped by "dog ears", their hair falling on the ears. Their musk-based fragrances earned them the nickname muscadins among the lower classes. They wore bicorne hats and carried bludgeons, which they referred to as their "executive power." They wore their hair at shoulder-length, sometimes pulled up in the back with a comb to imitate the hairstyles of the condemned. Some sported large monocles, and they frequently affected a lisp and sometimes a stooped hunchbacked posture as well.

In addition to Madame Tallien, known as "Our Lady of Thermidor", famous Merveilleuses included Mademoiselle Lange, Madame Récamier (who sat for a portrait by Jacques-Louis David), and Fortunée Hamelin and Hortense Beauharnais, two very popular Créoles. Hortense, a daughter of the Empress Josephine, married the King of Holland and became the mother of Napoleon III. Fortunée wasn't born to riches but became famous both for her salons and her string of prominent lovers. Parisian society compared Germaine de Staël and Mme Raguet to Minerva and Juno and named garments for Roman deities: gowns in were in the style of Flora or in the manner of Diana, not to mention tunics à la Ceres and Minerva.[3]

The leading Incroyable, Paul François Jean Nicolas, vicomte de Barras, was one of the five Directors who ran the Republic of France and gave the period its name. He hosted luxurious feasts, attended by royalists and repentant Jacobins, ladies and courtesans alike. Since divorce was now legal, sexuality tended to be looser than in the past. However de Barras' reputation for immorality may have been a factor in his later overthrow, in a coup that brought the Consulate to power and paved the way for Napoleon Bonaparte.

Representation in the Arts

The fictional nouveau riche social climber Madame Angot parodied the merveilleuses in many plays of the period, awkwardly wearing ridiculous Greek clothing. Carl Vernet's caricatures of the wardrobes of the Incroyables and Merveilleuses also met with contemporary popular success.

Images of the period

See also

- Salon (gathering)

- 1790s

- 1800-1809

- 1795-1820 in fashion

- Thermidorian Reaction

- Caricatures

- Paris Commune (French Revolution)

- Jean-Lambert Tallien

- Reign of Terror

- French Directory

- French Consulate

- Commune

- Guillotine

- Napoleon Bonaparte

- Caricatures

- Théâtre de Paris

- Bals des victimes

- Antoine-François Ève, playwright who wrote several plays featuring Madame Angot

- Thermidor et Directoire

Other meanings

Footnotes

- ^ Le Reveil du peuple or The Awakening of the People, written by Jean-Marie Souriguières de St Marc and set to music by Pierre Gaveau -- Lyrics on the French-language Wikipedia

- ^ Alain Rustenholz, Les traversées de Paris, Parigramme September 2006, Evreux, ISBN 2-84096-400-7

- ^ Alfred Richard Allinson, The days of the Directoire, pub J. Lane 1910, see p. 190

- ^ Lucky Meisenheimer. "Lucky’s History of the Yo-Yo". http://www.yo-yos.net/Yo-yo%20history.htm. Retrieved 2009-11-26.

Bibliography

- Barras, Paul; Mémoires de Barras, membre du Directoire (1895), Hachette, 1896

- Clarke, Joseph; Commemorating the Dead in Revolutionary France: Revolution and Remembrance, 1789-1799; Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- André Gaillot, ed. Une ancienne muscadine, Fortunée Hamelin: lettres inédites 1839-1851 (1911), Émile-Paul, 1911

External links

Categories:- History articles needing translation from French Wikipedia

- French Revolution

- Social history

- History of fashion

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.