- Typhoid Mary

-

For the fictional character, see Typhoid Mary (comics).

Mary Mallon Born September 23, 1869

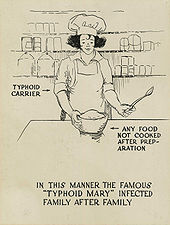

Cookstown, County Tyrone, IrelandDied November 11, 1938 (aged 69) Residence United States Nationality Ireland Known for Healthy carrier of typhoid fever Mary Mallon (September 23, 1869 – November 11, 1938), also known as Typhoid Mary, was the first person in the United States identified as an asymptomatic carrier of the pathogen associated with typhoid fever. She was presumed to have infected some 53 people, three of whom died, over the course of her career as a cook.[1] She was forcibly isolated twice by public health authorities and died after nearly three decades altogether in isolation.

Contents

Cook

Mary Mallon was born in 1869 in Cookstown, County Tyrone, Ireland, UK (now Northern Ireland). She emigrated to the United States in 1884. From 1900 to 1907 she worked as a cook in the New York City area.

In 1900, she had been working in a house in Mamaroneck, New York, for under two weeks when the residents developed typhoid fever. She moved to Manhattan in 1901, and members of the family for whom she worked developed fevers and diarrhea and the laundress died. She then went to work for a lawyer until seven of the eight household members developed typhoid; Mary spent months helping to care for the people she made sick, but her care further spread the disease through the household.[citation needed] In 1906, she took a position in Oyster Bay, Long Island. Within two weeks, ten of eleven family members were hospitalized with typhoid. She changed employment again, and similar occurrences happened in three more households.

When typhoid researcher George Soper approached Mallon about her possible role spreading typhoid, she adamantly rejected his request for urine and stool samples. Soper left and later published the report in June, 1907, in the Journal of the American Medical Association.[2] On his next contact with her, he brought a doctor with him, but was turned away again. Mallon's denials that she was a carrier were based in part on the diagnosis of a reputable chemist who had found her to not harbor the bacteria.[citation needed] Moreover, when Soper first told her she was a carrier, the concept of a healthy carrier of a pathogen was not commonly known. Further, class prejudice and prejudice towards the Irish were strong in the period, as was the belief that slum-dwelling immigrants were a major cause of epidemics. During a later encounter in the hospital, he told Mary that he would write a book about her and give her all the royalties; she angrily rejected his proposal and locked herself in the bathroom until he left.

Quarantine

The New York City Health Department sent Dr. Sara Josephine Baker to talk to Mary, but "by that time she was convinced that the law was only persecuting her when she had done nothing wrong."[3] A few days later, Baker arrived at Mary's workplace with several police officers who took her into custody. The New York City health inspector determined her to be a carrier. Under sections 1169 and 1170 of the Greater New York Charter, Mallon was held in isolation for three years at a clinic located on North Brother Island.

Individuals can develop typhoid fever after ingesting food or water contaminated during handling by a human carrier. The human carrier is usually a healthy person who has survived a previous episode of typhoid fever yet who continues to shed the associated bacteria, Salmonella typhi, in feces and urine. It takes vigorous scrubbing and thorough disinfection with soap and hot water to remove the bacteria from the hands.[citation needed]

Eventually, the New York State Commissioner of Health, Eugene H. Porter, M.D., decided that disease carriers would no longer be held in isolation. Mallon could be freed if she agreed to abandon working as a cook and to take reasonable steps to prevent transmitting typhoid to others. On February 19, 1910, Mallon agreed that she "[was] prepared to change her occupation (that of a cook), and would give assurance by affidavit that she would upon her release take such hygienic precautions as would protect those with whom she came in contact, from infection". She was released from quarantine and returned to the mainland.[4]

After being given a job as a laundress, which paid lower wages, however, Mallon adopted the pseudonym Mary Brown, returned to her previous occupation as a cook, and in 1915 was believed to have infected 25 people, resulting in one death, while working as a cook at New York's Sloane Hospital for Women. Public-health authorities again found and arrested Mallon, returned to quarantine on the island on March 27, 1915.[4] Mallon was confined there for the remainder of her life. She became something of a minor celebrity, and was interviewed by journalists, who were forbidden to accept even a glass of water from her. Later, she was allowed to work as a technician in the island's laboratory.

Death

Mallon spent the rest of her life in quarantine. Six years before her death, she was paralyzed by a stroke. On November 11, 1938, aged 69, she died of pneumonia.[1][3] An autopsy found evidence of live typhoid bacteria in her gallbladder.[5] It is possible that she was born with the infection, as her mother had typhoid fever during her pregnancy.[citation needed] Her body was cremated, and the ashes were buried at Saint Raymond's Cemetery in the Bronx.

Legacy

Mallon was the first healthy typhoid carrier to be identified by medical science, and there was no policy providing guidelines for handling the situation. Some difficulties surrounding her case stemmed from Mallon's vehement denial of her possible role, as she refused to acknowledge any connection between her working as a cook and the typhoid cases. Mallon maintained that she was perfectly healthy, had never had typhoid fever, and could not be the source. Public-health authorities determined that permanent quarantine was the only way to prevent Mallon from causing significant future typhoid outbreaks.

Other healthy typhoid carriers identified in the first quarter of the 20th century include Tony Labella, an Italian immigrant, presumed to have caused over 100 cases (with five deaths); an Adirondack guide dubbed Typhoid John, presumed to have infected 36 people (with two deaths); and Alphonse Cotils, a restaurateur and bakery owner.[6]

Today, Typhoid Mary is a generic term for a healthy carrier of a noted pathogen, especially one who refuses to cooperate with health authorities to minimize the risk of infection.[citation needed] The term is also applied to computer users who spread malicious computer software by their naïveté and neglect (or outright refusal) to use security software against the malware.[7] See also "Typhoid adware".

Mary Mallon is also referenced in popular culture in both the name of hip-hop group Hail Mary Mallon, and the name of Marvel comics character "Typhoid Mary".

References

- ^ a b "'Typhoid Mary' Dies Of A Stroke At 68. Carrier of Disease, Blamed for 51 Cases and 3 Deaths, but She Was Held Immune". New York Times. November 12, 1938. http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F10D15FE3859117389DDAB0994D9415B888FF1D3. Retrieved 2010-02-28. "Mary Mallon, the first carrier of typhoid bacilli identified in America and consequently known as Typhoid Mary, died yesterday in Riverside Hospital on North Brother Island."

- ^ Soper, George A. (1907-06-15). "The work of a chronic typhoid germ distributor". J Am Med Assoc 48: 2019–22.

- ^ a b Rosenberg, Jennifer. "Typhoid Mary". About.com. http://history1900s.about.com/library/weekly/aa062900b.htm. Retrieved 2007-06-06.

- ^ a b "Food Science Curriculum" (PDF). Illinois State Board of Education. p. 118. http://www.isbe.net/career/pdf/fcs_guide.pdf. Retrieved 2011-02-09.

- ^ Dex and McCaff, "Who was Typhoid Mary?" The Straight Dope, Aug 14, 2000

- ^ 20/Feb/2007 "The Board of Health’s Exile of Mary Mallon: Was it Justifiable?"

- ^ "Typhoid Mary" definition on "Flame Warriors".

Further reading

- Bourdain, Anthony. Typhoid Mary: An Urban Historical. New York: Bloomsbury, 2001. Hardcover, 148 pages, ISBN 1-58234-133-8

- Leavitt, Judith Walzer. Typhoid Mary, Captive to the Public's Health. Boston: Beacon Press, 1996. Hardcover, 331 pages, ISBN 0-8070-2102-4

- Baker, Josephine Sarah. Fighting for Life. New York: Macmillan Press, 1939. ISBN 0-405-05945-0 (1974 ed), ISBN 0-88275-611-7 (1980 ed)

- Federspiel, Jürg. The Ballad of Typhoid Mary [translated by Joel Agee]. New York: Ballantine Press, 1985.

- "Typhoid Mary". snopes.com. 2006-07-23. http://www.snopes.com/medical/disease/typhoid.asp.

- "Mary Mallon (Typhoid Mary)". Am J Public Health Nations Health 29 (1): 66–8. January 1939. doi:10.2105/AJPH.29.1.66. PMC 1529062. PMID 18014976. http://www.ajph.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=18014976.

- Aronson, S M (November 1995). "The civil rights of Mary Mallon". Rhode Island medicine 78 (11): 311–2. PMID 8547719.

- Brooks J (March 1996). "The sad and tragic life of Typhoid Mary". CMAJ 154 (6): 915–6. PMC 1487781. PMID 8634973. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1487781.

- Finkbeiner, Ann K (1996). "Quite contrary: was "Typhoid Mary" Mallon a symbol of the threats to individual liberty or a necessary sacrifice to public health?". The Sciences 36 (5): 38–43. PMID 11657398.

External links

- A more detailed profile of Typhoid Mary

- PBS NOVA site: "The Most Dangerous Woman in America"

- www.snopes.com about Typhoid Mary

- Photo of Mary Mallon's grave

Categories:- 1869 births

- 1938 deaths

- Deaths from pneumonia

- Irish emigrants to the United States (before 1923)

- People from Cookstown

- People from New York City

- People in public health

- Infectious disease deaths in New York

- People from Oyster Bay, New York

- Women and death

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.