- Cú Chulainn

-

For other uses, see Cú Chulainn (disambiguation).

Cú Chulainn ([kuːˈxʊlˠɪnʲ] (

listen), Irish for "Culann's Hound"), also spelled Cúchulainn, Cúchulain, Cú Ċulainn, Cúchullain or Cú Chulaind, is an Irish mythological hero who appears in the stories of the Ulster Cycle, as well as in Scottish and Manx[citation needed] folklore. The son of the god Lug and Deichtine (sister of Conchobar mac Nessa), he was originally named Sétanta.

listen), Irish for "Culann's Hound"), also spelled Cúchulainn, Cúchulain, Cú Ċulainn, Cúchullain or Cú Chulaind, is an Irish mythological hero who appears in the stories of the Ulster Cycle, as well as in Scottish and Manx[citation needed] folklore. The son of the god Lug and Deichtine (sister of Conchobar mac Nessa), he was originally named Sétanta.He gained his better-known name as a child after he killed Culann's fierce guard-dog in self-defence, and offered to take its place until a replacement could be reared. At the age of seventeen he defended Ulster single-handedly against the armies of queen Medb of Connacht in the epic Táin Bó Cúailnge ("Cattle Raid of Cooley"). It was prophesied that his great deeds would give him everlasting fame, but that his life would be a short one. This is the reason why he is compared to the Greek hero Achilles. He is known for his terrifying battle frenzy or ríastrad (similar to a berserker's frenzy, though sometimes called a "warp spasm" because of the physical changes that take place in the warrior),[1] in which he becomes an unrecognisable monster who knows neither friend nor foe. He fights from his chariot, driven by his loyal charioteer Láeg, and drawn by his horses, Liath Macha and Dub Sainglend. In more modern times, Cú Chulainn is often referred to as the "Hound of Ulster".[2]

Contents

Legends

Birth

Main article: Compert Con CulainnThere are a number of versions of the story of Cú Chulainn's birth. In the earliest version of Compert C(h)on Culainn ("The Conception of Cú Chulainn"), his mother Deichtine is the daughter and charioteer of Conchobar mac Nessa, king of Ulster, and accompanies him as he and the nobles of Ulster hunt a flock of magical birds. Snow falls, and the Ulstermen seek shelter, finding a house where they are made welcome. Their host's wife goes into labour, and Deichtine assists at the birth of a baby boy. A mare gives birth to two colts at the same time. The next morning, the Ulstermen find themselves at the Brug na Bóinde (the neolithic mound at Newgrange) — the house and its occupants have disappeared, but the child and the colts remain. Deichtine takes the boy home and raises him to early childhood, but he falls sick and dies. The god Lug appears to her and tells her he was their host that night, and that he has put his child in her womb, who is to be called Sétanta. Her pregnancy is a scandal as she is betrothed to Sualtam mac Róich, and the Ulstermen suspect Conchobar of being the father, so she aborts the child and goes to her husband's bed "virgin-whole". She then conceives a son whom she names Sétanta.[3]

In the later, and better-known, version of Compert Con Culainn, Deichtine is Conchobar's sister, and disappears from Emain Macha, the Ulster capital. As in the previous version, the Ulstermen go hunting a flock of magical birds, are overtaken by a snowstorm and seek shelter in a nearby house. Their host is Lug, but this time his wife, who gives birth to a son that night, is Deichtine herself. The child is named Sétanta.[4]

The nobles of Ulster argue over which of them is to be his foster-father, until the wise Morann decides he should be fostered by several of them: Conchobar himself; Sencha mac Ailella, who will teach him judgement and eloquent speech; the wealthy Blaí Briugu, who will protect and provide for him; the noble warrior Fergus mac Róich, who will care for him and teach him to protect the weak; the poet Amergin, who will educate him, and his wife Findchóem, who will nurse him. He is brought up in the house of Amergin and Findchóem on Muirthemne Plain in modern County Louth (at the time part of Ulster), alongside their son Conall Cernach.[5]

Childhood

The stories of Cú Chulainn's childhood are told in a flashback sequence in Táin Bó Cúailnge. As a small child, living in his parents' house on Muirthemne Plain, he begs to be allowed to join the boy-troop at Emain Macha. However, he sets off on his own, and when he arrives at Emain he runs onto the playing field without first asking for the boys' protection, being unaware of the custom. The boys take this as a challenge and attack him, but he has a ríastrad and beats them single-handed. Conchobar puts a stop to the fight and clears up the misunderstanding, but no sooner has Sétanta put himself under the boys' protection than he chases after them, demanding they put themselves under his protection.[6]

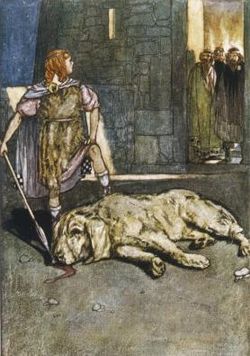

Culann the smith invites Conchobar to a feast at his house. Before going, Conchobar goes to the playing field to watch the boys play hurling. He is so impressed by Sétanta's performance that he asks him to join him at the feast. Sétanta has a game to finish, but promises to follow the king later. But Conchobar forgets, and Culann lets loose his ferocious hound to protect his house. When Sétanta arrives, the enormous hound attacks him, but he kills it in self-defence, in one version by smashing it against a standing stone, in another by driving a sliotar (hurling ball) down its throat with his hurley. Culann is devastated by the loss of his hound, so Sétanta promises he will rear him a replacement, and until it is old enough to do the job, he himself will guard Culann's house. The druid Cathbad announces that his name henceforth will be Cú Chulainn – "Culann's Hound".[7]

One day at Emain Macha, Cú Chulainn overhears Cathbad teaching his pupils. One asks him what that day is auspicious for, and Cathbad replies that any warrior who takes arms that day will have everlasting fame. Cú Chulainn, though only seven years old, goes to Conchobar and asks for arms. None of the weapons given to him withstand his strength, until Conchobar gives him his own weapons. But when Cathbad sees this he grieves, because he had not finished his prophecy — the warrior who took arms that day would be famous, but his life would be short. Soon afterwards, in response to a similar prophecy by Cathbad, Cú Chulainn demands a chariot from Conchobar, and only the king's own chariot withstands him. He sets off on a foray and kills the three sons of Nechtan Scéne, who had boasted they had killed more Ulstermen than there were Ulstermen still living. He returns to Emain Macha in his battle frenzy, and the Ulstermen are afraid he will slaughter them all. Conchobar's wife Mugain leads out the women of Emain, and they bare their breasts to him. He averts his eyes, and the Ulstermen wrestle him into a barrel of cold water, which explodes from the heat of his body. They put him in a second barrel, which boils, and a third, which warms to a pleasant temperature.[8]

Emer and Cú Chulainn's training

Main article: Tochmarc EmireIn Cú Chulainn's youth he is so beautiful the Ulstermen worry that, without a wife of his own, he will steal their wives and ruin their daughters. They search all over Ireland for a suitable wife for him, but he will have none but Emer, daughter of Forgall Monach. However, Forgall is opposed to the match. He suggests that Cú Chulainn should train in arms with the renowned warrior-woman Scáthach in the land of Alba (Scotland), hoping the ordeal will be too much for him and he will be killed. Cú Chulainn takes up the challenge. In the meantime, Forgall offers Emer to Lugaid mac Nóis, a king of Munster, but when he hears that Emer loves Cú Chulainn, Lugaid refuses her hand.

Scáthach teaches Cú Chulainn all the arts of war, including the use of the Gáe Bulg, a terrible barbed spear, thrown with the foot, that has to be cut out of its victim. His fellow trainees include Ferdiad, who becomes Cú Chulainn's best friend and foster-brother. During his time there, Scáthach faces a battle against Aífe, her rival and in some versions her twin sister. Scáthach, knowing Aífe's prowess, fears for Cú Chulainn's life and gives him a powerful sleeping potion to keep him from the battle. However, because of Cú Chulainn's great strength, it only puts him to sleep for an hour, and he soon joins the fray. He fights Aífe in single combat, and the two are evenly matched, but Cú Chulainn distracts her by calling out that Aífe's horses and chariot, the things she values most in the world, have fallen off a cliff, and seizes her. He spares her life on the condition that she call off her enmity with Scáthach, and bear him a son.

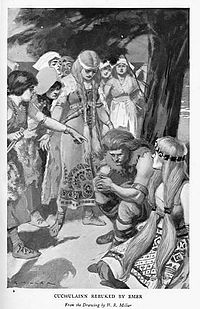

Leaving Aífe pregnant, Cú Chulainn returns from Scotland fully trained, but Forgall still refuses to let him marry Emer. Cú Chulainn storms Forgall's fortress, killing twenty-four of Forgall's men, abducts Emer and steals Forgall's treasure. Forgall himself falls from the ramparts to his death. Conchobar has the "right of the first night" over all marriages of his subjects. He is afraid of Cú Chulainn's reaction if he exercises it in this case, but is equally afraid of losing his authority if he does not. Cathbad suggests a solution: Conchobar sleeps with Emer on the night of the wedding, but Cathbad sleeps between them.[9]

Cú Chulainn kills his son

Eight years later, Connla, Cú Chulainn's son by Aífe, comes to Ireland in search of his father, but Cú Chulainn takes him as an intruder and kills him when he refuses to identify himself. Connla's last words to his father as he dies are that they would have "carried the flag of Ulster to the gates of Rome and beyond", leaving Cú Chulainn grief stricken.[10] The story of Cú Chulainn and Connla shows a striking similarity to the legend of Persian hero Rostam who also kills his son Sohrab. Rostam and Cú Chulainn share several other characteristics, including killing a ferocious beast at a very young age, their near invincibility in battle, and the manner of their deaths.[11]

Lugaid and Derbforgaill

During his time abroad, Cú Chulainn had rescued Derbforgaill, a Scandinavian princess, from being sacrificed to the Fomorians. She falls in love with him, and she and her handmaid come to Ireland in search of him in the form of a pair of swans. Cú Chulainn, not realising who she is, shoots her down with his sling, and then saves her life by sucking the stone from her side. Having tasted her blood, he cannot marry her, and gives her to his foster-son Lugaid Riab nDerg. Lugaid goes on to become High King of Ireland, but the Lia Fáil (stone of destiny), fails to cry out when he stands on it, so Cú Chulainn splits it in two with his sword.[12] When Derbforgaill is mutilated by the women of Ulster out of jealousy for her sexual desirability and dies of her wounds, Lugaid dies of grief, and Cú Chulainn avenges them by demolishing the house the women are inside, killing 150 of them.[13]

The Cattle Raid of Cooley

Main article: Táin Bó CúailngeAt the age of seventeen, Cú Chulainn single-handedly defends Ulster from the army of Connacht in the Táin Bó Cúailnge. Medb, queen of Connacht, has mounted the invasion to steal the stud bull Donn Cúailnge, and Cú Chulainn allows her to take Ulster by surprise because he is with a woman when he should be watching the border. The men of Ulster are disabled by a curse, so Cú Chulainn prevents Medb's army from advancing further by invoking the right of single combat at fords. He defeats champion after champion in a stand-off lasting months.

Before one combat a beautiful young woman comes to him, claiming to be the daughter of a king, and offers him her love, but he refuses her. The woman reveals herself as the Morrígan, and in revenge for this slight she attacks him in various animal forms while he is engaged in combat against Lóch mac Mofemis. As an eel, she trips him in the ford, but he breaks her ribs. As a wolf, she stampedes cattle across the ford, but he puts out her eye with a sling-stone. Finally she appears as a heifer at the head of the stampede, but he breaks her leg with another slingstone. After Cú Chulainn finally defeats Lóch, the Morrígan appears to him as an old woman milking a cow, with the same injuries he had given her in her animal forms. She gives him three drinks of milk, and with each drink he blesses her, healing her wounds.

After one particularly arduous combat Cú Chulainn lies severely wounded, but is visited by Lug, who tells him he is his father and heals his wounds. When Cú Chulainn wakes up and sees that the boy-troop of Emain Macha have attacked the Connacht army and been slaughtered, he has his most spectacular ríastrad yet:

“ The first warp-spasm seized Cúchulainn, and made him into a monstrous thing, hideous and shapeless, unheard of. His shanks and his joints, every knuckle and angle and organ from head to foot, shook like a tree in the flood or a reed in the stream. His body made a furious twist inside his skin, so that his feet and shins switched to the rear and his heels and calves switched to the front... On his head the temple-sinews stretched to the nape of his neck, each mighty, immense, measureless knob as big as the head of a month-old child... he sucked one eye so deep into his head that a wild crane couldn't probe it onto his cheek out of the depths of his skull; the other eye fell out along his cheek. His mouth weirdly distorted: his cheek peeled back from his jaws until the gullet appeared, his lungs and his liver flapped in his mouth and throat, his lower jaw struck the upper a lion-killing blow, and fiery flakes large as a ram's fleece reached his mouth from his throat... The hair of his head twisted like the tange of a red thornbush stuck in a gap; if a royal apple tree with all its kingly fruit were shaken above him, scarce an apple would reach the ground but each would be spiked on a bristle of his hair as it stood up on his scalp with rage. ” —Thomas Kinsella (translator), The Táin, Oxford University Press, 1969, pp. 150-153

He attacks the army and kills hundreds, building walls of corpses.

When his foster-father Fergus mac Róich, now in exile in Medb's court, is sent to face him Cú Chulainn agrees to yield, so long as Fergus agrees to return the favour the next time they meet. Finally, he fights a gruelling three-day duel with his best friend and foster-brother, Ferdiad, at a ford that was named Áth Fhir Diadh (Ardee, County Louth) after him.

The Ulstermen eventually rouse, one by one at first, and finally en masse. The final battle begins. Cú Chulainn stays on the sidelines, recuperating from his wounds, until he sees Fergus advancing. He enters the fray and confronts Fergus, who keeps his side of the bargain and yields to him, pulling his forces off the field. Connacht's other allies panic and Medb is forced to retreat. At this inopportune moment she gets her period, and although Fergus forms a guard around her, Cú Chulainn breaks through as she is dealing with it and has her at his mercy. However he spares her because he does not think it right to kill women, and guards her retreat back to Connacht as far as Athlone.[14][15][16]

Bricriu's Feast

Main article: Fled BricrennThe troublemaker Bricriu once incites three heroes, Cú Chulainn, Conall Cernach and Lóegaire Búadach, to compete for the champion's portion at his feast. In every test that is set Cú Chulainn comes out top, but neither Conall nor Lóegaire will accept the result. Cú Roí mac Dáire of Munster settles it by visiting each in the guise of a hideous churl and challenging them to behead him, then allow him to return and behead them in return. Conall and Lóegaire both behead Cú Roí, who picks up his head and leaves, but when the time comes for him to return they flee. Only Cú Chulainn is brave and honourable enough to submit himself to Cú Roí's axe; Cú Roí spares him and he is declared champion.[17] This beheading challenge appears in later literature, most notably in the Middle English poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Other examples include the 13th century French Life of Caradoc and the English romances The Turke and Gowin, and Sir Gawain and the Carle of Carlisle.

The Death of Cú Roí

Cú Roí, again in disguise, joins the Ulstermen on a raid on Inis Fer Falga (probably the Isle of Man), in return for his choice of the spoils. They steal treasure, and abduct Blathnát, daughter of the island's king, who loves Cú Chulainn. But when Cú Roí is asked to choose his share, he chooses Blathnát. Cú Chulainn tries to stop him taking her, but Cú Roí cuts his hair and drives him into the ground up to his armpits before escaping, taking Blathnát with him. Like other heroes such as the Biblical Samson, Duryodhana in the Mahabharata and the Welsh Llew Llaw Gyffes, Cú Roí can only be killed in certain contrived circumstances, which vary in different versions of the story. Blathnat discovers how to kill him and betrays him to Cú Chulainn, who does the deed. However Ferchertne, Cú Roí's poet, enraged at the betrayal of his lord, grabs Blathnát and leaps off a cliff, killing her and himself.[18]

Emer's only jealousy

Main article: Serglige Con CulainnCú Chulainn has many lovers, but Emer's only jealousy comes when he falls in love with Fand, wife of Manannán mac Lir. Manannán has left her and she has been attacked by three Fomorians who want to control the Irish Sea. Cú Chulainn agrees to help defend her as long as she marries him. She agrees reluctantly, but they fall in love when they meet. Manannán knows their relationship is doomed because Cú Chulainn is mortal and Fand is a fairy; Cú Chulainn's presence would destroy the fairies. Emer, meanwhile, tries to kill her rival, but when she sees the strength of Fand's love for Cú Chulainn she decides to give him up to her. Fand, touched by Emer's magnanimity, decides to return to her own husband. Manannan shakes his cloak between Cú Chulainn and Fand, ensuring the two will never meet again, and Cú Chulainn and Emer drink a potion to wipe the whole affair from their memories.[19]

Cú Chulainn's death

The figure of Cú Chulainn was used to commemorate the Easter Rising on the ten shilling coin

The figure of Cú Chulainn was used to commemorate the Easter Rising on the ten shilling coin

(Irish - Aided con Culainn) Medb conspires with Lugaid, son of Cú Roí, Erc, son of Cairbre Nia Fer, and the sons of others Cú Chulainn had killed, to draw him out to his death. His fate is sealed by his breaking of the geasa (taboos) upon him. Cú Chulainn's geasa included a ban against eating dog meat, but in early Ireland there was a powerful general taboo against refusing hospitality, so when an old crone offers him a meal of dog meat, he has no choice to break his geis. In this way he is spiritually weakened for the fight ahead of him.

Lugaid has three magical spears made, and it is prophesied that a king will fall by each of them. With the first he kills Cú Chulainn's charioteer Láeg, king of chariot drivers. With the second he kills Cú Chulainn's horse, Liath Macha, king of horses. With the third he hits Cú Chulainn, mortally wounding him. Cú Chulainn ties himself to a standing stone in order to die on his feet. This stone is traditionally identified as one still standing at Knockbridge, County Louth.[20] Due to his ferocity even when so near death, it is only when a raven lands on his shoulder that his enemies believe he is dead. Lugaid approaches and cuts off his head, but as he does so the "hero-light" burns around Cú Chulainn and his sword falls from his hand and cuts Lugaid's hand off. The light disappears only after his right hand, his sword arm, is cut from his body.

Conall Cernach had sworn that if Cú Chulainn died before him he would avenge him before sunset, and when he hears Cú Chulainn is dead he pursues Lugaid. As Lugaid has lost a hand, Conall fights him with one hand tucked into his belt, but he only beats him after his horse takes a bite out of Lugaid's side. He also kills Erc, and takes his head back to Tara, where Erc's sister Achall dies of grief for her brother.[21]

Later stories

The story is told that when Saint Patrick was trying to convert king Lóegaire to Christianity, the ghost of Cú Chulainn appeared in his chariot, warning him of the torments of hell.[22]

Appearance

Cú Chulainn's appearance is occasionally remarked on in the texts. He is usually described as small, youthful and beardless. He is often described as dark: in The Wooing of Emer and Bricriu's Feast he is "a dark, sad man, comeliest of the men of Erin",[23] in The Intoxication of the Ulstermen he is a "little, black-browed man",[24] and in The Phantom Chariot of Cú Chulainn "[h]is hair was thick and black, and smooth as though a cow had licked it... in his head his eyes gleamed swift and grey";[25] yet the prophetess Fedelm in the Táin Bó Cúailnge describes him as blond.[26] The most elaborate description of his appearance comes later in the Táin:

“ And certainly the youth Cúchulainn mac Sualdaim was handsome as he came to show his form to the armies. You would think he had three distinct heads of hair – brown at the base, blood-red in the middle, and a crown of golden yellow. This hair was settled strikingly into three coils on the cleft at the back of his head. Each long loose-flowing strand hung down in shining splendour over his shoulders, deep-gold and beautiful and fine as a thread of gold. A hundred neat red-gold curls shone darkly on his neck, and his head was covered with a hundred crimson threads matted with gems. He had four dimples in each cheek – yellow, green, crimson and blue – and seven bright pupils, eye-jewels, in each kingly eye. Each foot had seven toes and each hand seven fingers, the nails with the grip of a hawk's claw or a gryphon's clench. ” —Thomas Kinsella (translator), The Táin, Oxford University Press, 1969, pp. 156-158

Cultural depictions of Cú Chulainn

Images

The image of Cú Chulainn is invoked by both Irish nationalists and Ulster unionists. Irish nationalists see him as the most important Celtic Irish hero, and thus he is important to their whole culture. A bronze sculpture of the dying Cú Chulainn by Oliver Sheppard stands in the Dublin General Post Office (GPO) in commemoration of the Easter Rising of 1916. By contrast, unionists see him as an Ulsterman defending the province from enemies to the south: in Belfast, for example, he is depicted in a mural on Highfield Drive, and was formerly depicted in a mural on the Newtownards Road, as a "defender of Ulster from Irish attacks", both murals ironically based on the Sheppard sculpture.[27] He is also depicted in murals in nationalist parts of the city and many nationalist areas of Northern Ireland.[28]

Samuel Beckett once asked a friend to go to the GPO and "measure the height of the ground to Cúchulainn’s arse", as Neary in his novel Murphy wished to "engage with the arse of the statue of Cúchulainn, the ancient Irish hero, patron saint of pure ignorance and crass violence, by banging his head against it."[29] The statue's image was also used on the ten shilling coin produced for 1966.

A statue of Cú Chulainn carrying the body of Fer Diad stands in Ardee, County Louth, traditionally the site of their combat in the Táin Bó Cúailnge.[30]

Literature

Augusta, Lady Gregory retold many of the legends of Cú Chulainn in her 1902 book Cuchulain of Muirthemne, which closely paraphrased the originals but glossed over some of the more sexual extreme content, given the conventional prudery of her day. Where he is surrounded by 150 naked ladies, Lady Gregory described them as only having bared breasts. This first translation was a great success, supported by the Celtic Revival movement. It featured an introduction by her friend William Butler Yeats, who wrote several pieces based on the legend, including the plays On Baile's Strand (1904), The Green Helmet (1910), At the Hawk's Well (1917), The Only Jealousy of Emer (1919) and The Death of Cuchulain (1939), and a poem, Cuchulain's Fight with the Sea (1892).[20] Modern novels which retell Cú Chulainn's story include Rosemary Sutcliff's 1963 children's novel The Hound of Ulster, Morgan Llywelyn's 1989 historical novel Red Branch, Randy Lee Eickhoff's series of adaptations, Manfred Böckl's German language novel Der Hund des Culann, and Holly Bennett's The Warrior's Daughter, which tells the story from the point of view of his daughter, Luaine. The legends of Cú Chulainn also appear occasionally in Frank McCourt's bestselling 1996 memoir Angela's Ashes. The fictional horror book "The Shee", written by British author Joe Donnelly, is heavily steeped in Celtic mythology and a major part of the book's plot is based on the warrior Cu Chulainn.

Music

Irish band Horslips released The Táin in 1973, a concept album based on the Táin Bó Cúailnge.

Irish rock band Thin Lizzy references Cú Chulainn on the song named 'Róisín Dubh (Black Rose): A Rock Legend' on their album 'Black Rose: A Rock Legend' in the second verse: "Pray tell me the story of young Cuchulainn; How his eyes were dark, his expression sullen; And how he'd fight and always won; And how they cried when he was fallen."

Swedish symphonic metal band Therion has a song titled Cú Chulainn on their 2010 album, Sitra Ahra.

Italian epic metal band Doomsword have a song titled Death of Ferdia on their 2007 album, My Name Will Live On.

German melodic death metal band Suidakra's 2009 album, Crógacht , is a retelling of the story of Cuchulainn and his son Conlaoch (known in the Ulster Cycle as Aided Óenfhir Aífe, The Death of Aífe's Only Son).

Canadian flautist Ron Korb has a song titled Cuchulainn on his 2000 album, Celtic Heartland.

American heavy metal artist Glenn Danzig references Cú Chulainn in his song "Left Hand Black" in the opening lines: "Kinda like a dog with seven pupils in its eye". See the meaning of the hero's name and the description of his appearance found above.

The movie The Boondock Saints main theme is a song titled Blood Of Cu Chulainn by Canadian musician and composer Jeff Danna that was released in 1999. Ten years later he composed the album to the sequel The Boondock Saints II: All Saints Day and this song was remixed under the title Blood Of Cu Chulainn 2010.

Irish band The Pogues (formerly Pogue Mahone) have a track named 'The Sick Bed Of Cuchulainn' on their album 'Rum, Sodomy And The Lash'.

The French rap group Manau produced on its first album 'Panique Celtique' (1998) a song titled Le chien du forgeron (The blacksmith's hound), about the story of Cú Chulainn.

Black Francis (a.k.a. Frank Black) references Cú Chulainn in his mini-album svn fngrs. The songs "Seven Fingers" and "When They Come to Murder Me" feature lyrics written from Cú Chulainn's point of view.

The first track on Adiemus IV: The Eternal Knot is called Cú Chullain.

The last track on the album Zero To Rage from Irish heavy metal band Stormzone is entitled Cuchulainn's Story.

TV

Cú Chulainn appeared in Episode 45 of the Disney animated series Gargoyles entitled "The Hound Of Ulster".

Video Games

Cúchulainn is the protagonist and playable character in the 1984 game Tir Na Nog and its sequel Dun Darach by Gargoyle Games. The games included heavy references to celtic mythology and folklore.

In the 1997 game Final Fantasy Tactics, Cúchulainn is depicted as one of the Lucavi, a demon that possesses the Cardinal Delocroix.

In the game Final Fantasy XII, the name appears on an Esper under the name "Cúchulainn, the Impure", who can be found in the sluice and sewers of the game's initial castle-city. His purpose was to swallow the world's impurities. "The world, however, was more filled with impurity and corruption than even the gods dared imagine, and having swallowed it all, the once beautiful Cúchulainn was transformed into a hideous thing, a deity of filth, and so did he turn against his creators. Wherever his feet should fall, there all life withers to dust." In the game, he is associated with the Scorpio constellation of the zodiac; his special abilities aptly revolve around toxin and poison.

He appears in the game/anime Fate/Stay Night as the Servant Lancer; the only clue to his identity is his lance's name, Gae Bulg.

Cu Chulainn also appears in the Megami Tensei series, as well as its spinoff series such as Shin Megami Tensei: Persona. In his latest incarnations he is depicted with long, straight black hair and clad in white armour with black designs, with a cape and loincloth as well as his trademark lance.

Card Games

In the Yu-Gi-Oh! Trading Card Game, Cúchulainn is a Ritual Monster known as Cú Chulainn the Awakened. It can be summoned by using the Ritual Spell Emblem of the Awakening.

See also

- Gáe Bulg, Cu Chullain's enchanted spear

- Irish mythology in popular culture: Cú Chulainn

Notes

- ^ Literally "the act of contorting, a distortion" (Dictionary of the Irish Language, Compact Edition, Royal Irish Academy, Dublin, 1990, p. 507)

- ^ Hull, E. Cuchulain the Hound of Ulster (London, Harrap, 1913). Sutcliff, R., The Hound of Ulster (London, Red Fox, 1992). "The Hound of Ulster", BBC

- ^ A.G. van Hamel (ed.), Compert Con Culainn and Other Stories, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1978, pp. 3-8.

- ^ Tom Peete Cross & Clark Harris Slover (eds.), Ancient Irish Tales, Henry Holt & Company, 1936 (reprinted by Barnes & Noble, 1996), pp. 134-136

- ^ Thomas Kinsella (trans.), The Táin, Oxford University Press, 1969, ISBN 0192810901, pp. 23-25

- ^ Kinsella 1969, pp. 76-78.

- ^ Kinsella 1969, pp. 82-84; Cecile O'Rahilly (ed. & trans.), Táin Bó Cúalnge from the Book of Leinster, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1967, pp. 159-163

- ^ Kinsella 1969, pp. 84-92

- ^ Kuno Meyer (ed. & trans.), "The oldest version of Tochmarc Emire", Revue Celtique 11, 1890, pp. 433-57

- ^ Kuno Meyer (ed. & trans.), "The death of Connla", Ériu 1, 1904, pp. 113-121

- ^ Connell Monette, The Medieval Hero: Christian and Muslim Traditions. (Saarsbruck: 2008), pp.91-121.

- ^ Lebor Gabála Érenn §57

- ^ Carl Marstrander (ed. & trans.), "The Deaths of Lugaid and Derbforgaill", Ériu 5, 1911, pp. 201-218

- ^ Kinsella 1969, pp. 52-253

- ^ Cecile O'Rahilly (ed. & trans.), Táin Bó Cúalnge from the Book of Leinster, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1967

- ^ Cecile O'Rahilly (ed. & trans.), Táin Bó Cúailnge Recension 1, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1976

- ^ Jeffrey Gantz (trans.), Early Irish Myths & Sagas, Penguin, 1981, pp. 219-255

- ^ R. I. Best (ed. & trans.), "The Tragic Death of Cúrói mac Dári", Ériu 2, 1905, pp. 18-35

- ^ A. H. Leahy (trans.), Historic Romances of Ireland Vol 1, 1905, pp. 51-85

- ^ a b James MacKillop, Dictionary of Celtic Mythology, Oxford University Press, 1998, p. 104

- ^ Whitley Stokes (ed. trans.), "Cuchulainn's death, abridged from the Book of Leinster", Revue Celtique 3, 1877, pp. 175-185

- ^ J. O'Beirne Crowe (ed. & trans.), "Siabur-charpat Con Culaind", Journal of the Royal Historical and Archaeological Association of Ireland series 4, vol 1, 1870, pp. 371-401

- ^ Cross & Slover 1936, p. 156, 265

- ^ Cross & Slover 1936, p. 227

- ^ Cross & Slover 1936, p. 348

- ^ Kinsella 1969, p. 61

- ^ Photographs of the Newtownards Road mural and the Highfield Drive mural

- ^ Photos of murals on Ardoyne Avenue and Falcarragh Road

- ^ "Colm Tóibín on Beckett’s Irish Actors", London Review of Books Vol 29 No 7, 5 April 2007

- ^ Statue of Cuchulainn & Ferdia in Ardee

References

Secondary sources

Primary sources

- Compert Con Culainn (Recension I), ed. A.G. van Hamel (1933). Compert Con Culainn and Other Stories. Mediaeval and Modern Irish Series 3. Dublin: DIAS. pp. 1-8. http://www.ucc.ie/celt/published/G301013

Compert Con Culainn (Recension II), ed. Kuno Meyer (1905). "Mitteilungen aus irischen Handschriften: Feis Tige Becfoltaig". Zeitschrift für celtische Philologie 5: 500-4 (from D IV 2). http://www.archive.org/details/zeitschriftfrc05meyeuoft; ed. Ernst Windisch (1880). Irische Texte mit Wörterbuch. Leipzig. pp. 143-5 and 140-2 (from Egerton 1782). http://www.archive.org/stream/irischetextemit00lucagoog.

- Tochmarc Emire (Recension I), ed. and tr. Kuno Meyer (1890). "The Oldest Version of Tochmarc Emire". Revue Celtique 11: 433–57. CELT link.

- Tochmarc Emire (Recension II), ed. A.G. van Hamel (1933). Compert Con Culainn and Other Stories. Mediaeval and Modern Irish Series 3. Dublin: DIAS; tr. Kuno Meyer (1888). "The Wooing of Emer". Archaeological Review 1: 68–75, 150–5, 231–5, 298–307. http://www.ucc.ie/celt/online/T301021.

- Serglige Con Culainn, ed. Myles Dillon (1953). Serglige Con Culainn. Mediaeval and Modern Irish Series 14. Dublin: DIAS. http://www.ucc.ie/celt/published/G301015.; tr. Jeffrey Gantz (1981). Early Irish Myths and Sagas. London: Penguin. pp. 155–78.

- Modern literature

- Sutcliff, Rosemary (1992). The Hound of Ulster. London: Red Fox.

Further reading

- Bruford, Alan (1994). "Cú Chulainn - An Ill-Made Hero?". In Hildegard L. C. Tristram. Text und Zeittiefe. ScriptOralia 58. Tubingen: Gunter Narr. pp. 185–215.

- Carey, John (1999). "Cú Chulainn as Ailing Hero". In Ronald Black, William Gillies, and Roibeard Ó Maolalaigh. Celtic Connections: Proceedings of the Tenth International Congress of Celtic Studies, Vol. 1. East Linton: Tuckwell. pp. 190–8.

- Gray, Elizabeth A. (1989/90). "Lug and Cú Chulainn: King and Warrior". Studia Celtica 24/25: 38–52.

- Jaski, Bart (1999). "Cú Chulainn, gormac and dalta of the Ulstermen'". Cambrian Medieval Celtic Studies 37: 1–31.

- Nagy, Joseph Falaky (1984). "Heroic Destinies in the Macgnímrada of Finn and Cú Chulainn". Zeitschrift für celtische Philologie 40: 23–39.

- Sayers, William (1985). "The Smith and the Hero: Culann and Cú Chulainn". Mankind Quarterly 25.3: 227–60.

External links

Texts in translation

- The Birth of Cú Chulainn

- Tidings of Conchobar son of Ness

- The Boyhood Deeds of Cú Chulainn

- The Wooing of Emer

- The Death of Aífe's Only Son

- The Cattle Raid of Regamna

- Bricriu's Feast

- The Cattle Raid of Cooley: Recension 1, Recension 2

- The Battle of Ross na Ríg

- The Death of Cú Roí

- The Sick-Bed of Cuchulain

- The Pursuit of Gruaidh Ghriansholus

- The Death of Cú Chulainn

- The Phantom Chariot of Cú Chulainn

Modern retellings

- Cuchulain of Muirthemne, by Lady Gregory

- The Boys' Cúchullain by Eleanor Hull (1904) at The Baldwin Project

File:'Cú Chulainn's Lament' Graphic Novel -Thumbnail.jpg

Categories:- Characters in Táin Bó Cúailnge

- Monomyths

- Mythological heroes

- Ulster Cycle

- 1st-century Irish people

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.