- Ornette Coleman

-

Ornette Coleman

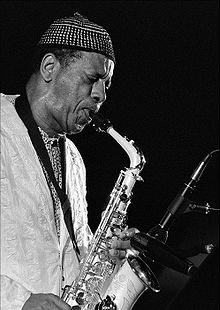

Ornette Coleman plays his Selmer alto saxophone during a performance at The Hague, 1994.Background information Born March 9, 1930

Fort Worth, Texas, United StatesGenres Free jazz, Free funk, Avant-garde jazz, Jazz-rock Occupations musician, composer Instruments alto saxophone, tenor saxophone, violin, trumpet Years active 1958–present Website ornettecoleman.com Ornette Coleman (born March 9, 1930)[1] is an American saxophonist, violinist, trumpeter and composer. He was one of the major innovators of the free jazz movement of the 1960s.

Coleman's timbre is easily recognized: his keening, crying sound draws heavily on blues music. His album Sound Grammar received the 2007 Pulitzer Prize for music.

Contents

Biography

Early life

Coleman was born and raised in Fort Worth, Texas, where he began performing R&B and bebop initially on tenor saxophone. Seeking a way to work his way out of his home town, he took a job in 1949 with a Silas Green from New Orleans traveling show and then with touring rhythm and blues shows. After a show in Baton Rouge, he was assaulted and his saxophone was destroyed.[2]

He switched to alto, which has remained his primary instrument, first playing it in New Orleans after the Baton Rouge incident. He then joined the band of Pee Wee Crayton and travelled with them to Los Angeles. He worked at various jobs, including as an elevator operator, while still pursuing his musical career.

Even from the beginning of Coleman's career, his music and playing were in many ways unorthodox. His approach to harmony and chord progression was far less rigid than that of bebop performers; he was increasingly interested in playing what he heard rather than fitting it into predetermined chorus-structures and harmonies. His raw, highly vocalized sound and penchant for playing "in the cracks" of the scale led many Los Angeles jazz musicians to regard Coleman's playing as out-of-tune. He sometimes had difficulty finding like-minded musicians with whom to perform. Nevertheless, pianist Paul Bley was an early supporter and musical collaborator.

In 1958, Coleman led his first recording session for Contemporary, Something Else!!!!: The Music of Ornette Coleman. The session also featured trumpeter Don Cherry, drummer Billy Higgins, bassist Don Payne and Walter Norris on piano.[1]

The Shape of Jazz to Come

Coleman was very busy in 1959. His last release on Contemporary was Tomorrow Is the Question!, a quartet album, with Shelly Manne on drums, and excluding the piano, which he would not use again until the 1990s. Next Coleman brought double bassist Charlie Haden – one of a handful of his most important collaborators – into a regular group with Haden, Cherry, and Higgins. (All four had played with Paul Bley the previous year.) He signed a multi-album contract with Atlantic Records who released The Shape of Jazz to Come in 1959. It was, according to critic Steve Huey, "a watershed event in the genesis of avant-garde jazz, profoundly steering its future course and throwing down a gauntlet that some still haven't come to grips with."[3] While definitely – if somewhat loosely – blues-based and often quite melodic, the album's compositions were considered at that time harmonically unusual and unstructured. Some musicians and critics saw Coleman as an iconoclast; others, including conductor Leonard Bernstein and composer Virgil Thomson regarded him as a genius and an innovator.[4]

Coleman's quartet received a lengthy – and sometimes controversial – engagement at New York City's famed Five Spot jazz club. Such notable figures as the Modern Jazz Quartet, Leonard Bernstein and Lionel Hampton were favorably impressed, and offered encouragement. (Hampton was so impressed he reportedly asked to perform with the quartet; Bernstein later helped Haden obtain a composition grant from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation.) Opinion was, however, divided. Trumpeter Miles Davis famously declared Coleman was "all screwed up inside" (although this comment was later recanted) and Roy Eldridge stated, "I'd listened to him all kinds of ways. I listened to him high and I listened to him cold sober. I even played with him. I think he's jiving baby."[5]

On the Atlantic recordings, Scott LaFaro sometimes replaces Charlie Haden on double bass and either Billy Higgins or Ed Blackwell features on drums. These recordings are collected in a boxed set, Beauty Is a Rare Thing.[1]

Part of the uniqueness of Coleman's early sound came from his use of a plastic saxophone. He had first bought a plastic horn in Los Angeles in 1954 because he was unable to afford a metal saxophone, though he didn't like the sound of the plastic instrument at first.[6] Coleman later claimed that it sounded drier, without the pinging sound of metal. In more recent years, he has played a metal saxophone.[7]

Free Jazz

In 1960, Coleman recorded Free Jazz: A Collective Improvisation, which featured a double quartet, including Cherry and Freddie Hubbard on trumpet, Eric Dolphy on bass clarinet, Haden and LaFaro on bass, and both Higgins and Blackwell on drums. The record was recorded in stereo, with a reed/brass/bass/drums quartet isolated in each stereo channel. Free Jazz was, at nearly 40 minutes, the lengthiest recorded continuous jazz performance to date, and was instantly one of Coleman's most controversial albums. The music features a regular but complex pulse, one drummer playing "straight" while the other played double-time; the thematic material is a series of brief, dissonant fanfares. As is conventional in jazz, there are a series of solo features for each member of the band, but the other soloists are free to chime in as they wish, producing some extraordinary passages of collective improvisation by the full octet.

Coleman intended "Free Jazz" simply to be the album title, but his growing reputation placed him at the forefront of jazz innovation, and free jazz was soon considered a new genre, though Coleman has expressed discomfort with the term. Among the reasons Coleman may not have entirely approved of the term 'free jazz' is that his music contains a considerable amount of composition. His melodic material, although skeletal, strongly recalls the melodies that Charlie Parker wrote over standard harmonies, and in general the music is closer to the bebop that came before it than is sometimes popularly imagined. (Several early tunes of his, for instance, are clearly based on favorite bop chord changes like "Out of Nowhere" and "I Got Rhythm".) Coleman very rarely played standards, concentrating on his own compositions, of which there seems to be an endless flow. There are exceptions, though, including a classic reading (virtually a recomposition) of "Embraceable You" for Atlantic, and an improvisation on Thelonious Monk's "Criss-Cross" recorded with Gunther Schuller.

1960s

After the Atlantic period and into the early part of the 1970s, Coleman's music became more angular and engaged fully with the jazz avant-garde which had developed in part around Coleman's innovations.[1]

His quartet dissolved, and Coleman formed a new trio with David Izenzon on bass, and Charles Moffett on drums. Coleman began to extend the sound-range of his music, introducing accompanying string players (though far from the territory of Charlie Parker with Strings) and playing trumpet and violin (which he played left-handed) himself. He initially had little conventional technique and used the instruments to make large, unrestrained gestures. His friendship with Albert Ayler influenced his development on trumpet and violin. Haden would later sometimes join this trio to form a two-bass quartet.

Between 1965 and 1967 Coleman signed with Blue Note Records and released a number of recordings starting with the influential recordings of the trio At the Golden Circle Stockholm.

In 1966, Coleman was criticized for recording The Empty Foxhole, a trio with Haden, and Coleman's son Denardo Coleman – who was ten years old. Some[who?] regarded this as perhaps an ill-advised piece of publicity on Coleman's part and judged the move a mistake. Others, however,[who?] noted that despite his youth, Denardo had studied drumming for several years. His technique – which, though unrefined, was respectable and enthusiastic – owed more to pulse-oriented free jazz drummers like Sunny Murray than to bebop drumming. Denardo has matured into a respected musician, and has been his father's primary drummer since the late 1970s.

Coleman formed another quartet. A number of bassists and drummers (including Haden, Jimmy Garrison and Elvin Jones) appeared, and Dewey Redman joined the group, usually on tenor saxophone.

He also continued to explore his interest in string textures – from the Town Hall concert in 1962, culminating in Skies of America in 1972. (Sometimes this had a practical value, as it facilitated his group's appearance in the UK in 1965, where jazz musicians were under a quota arrangement but classical performers were exempt.)

In 1969, Coleman was inducted into the Down Beat Jazz Hall of Fame

Later career

Coleman, like Miles Davis before him, took to playing with electrified instruments. Albums like Virgin Beauty and Of Human Feelings used rock and funk rhythms, sometimes called free funk. On the face of it, this could seem to be an adoption of the jazz fusion mode fashionable at the time, but Ornette's first record with the group, which later became known as Prime Time (the 1976 Dancing in Your Head), was sufficiently different to have considerable shock value. Electric guitars were prominent, but the music was, at heart, rather similar to his earlier work. These performances have the same angular melodies and simultaneous group improvisations – what Joe Zawinul referred to as "nobody solos, everybody solos" and what Coleman calls harmolodics – and although the nature of the pulse has altered, Coleman's own rhythmic approach has not.

Some critics[who?] have suggested Coleman's frequent use of the vaguely-defined term harmolodics is a musical MacGuffin: a red herring of sorts designed to occupy critics overly-focused on Coleman's sometimes unorthodox compositional style.

Jerry Garcia played guitar on three tracks from Coleman's Virgin Beauty (1988): "Three Wishes," "Singing In The Shower," and "Desert Players." Coleman joined the Grateful Dead on stage twice in 1993 playing the band's "The Other One," "Wharf Rat," "Stella Blue," and covering Bobby Bland's "Turn On Your Lovelight," among others.[8] Another unexpected association was with guitarist Pat Metheny, with whom Coleman recorded Song X (1985); though released under Metheny's name, Coleman was essentially co-leader (contributing all the compositions).

In 1990, the city of Reggio Emilia in Italy held a three-day "Portrait of the Artist" featuring a Coleman quartet with Don Cherry, Charlie Haden and Billy Higgins. The festival also presented performances of his chamber music and the symphonic Skies of America.

In 1991, Coleman played on the soundtrack for David Cronenberg's Naked Lunch; the orchestra was conducted by Howard Shore. It is notable among other things for including a rare sighting of Coleman playing a jazz standard: Thelonious Monk's blues line “Misterioso.” Two 1972 (pre-electric) Coleman recordings, "Happy House" and "Foreigner in a Free Land" were used in Gus Van Sant's 1995 Finding Forrester.

The mid-1990s saw a flurry of activity from Coleman: he released four records in 1995 and 1996, and for the first time in many years worked regularly with piano players (either Geri Allen or Joachim Kühn).

Coleman has rarely performed on other musicians' records. Exceptions include extensive performances on albums by Jackie McLean in 1967 (New and Old Gospel, on which he played trumpet), and James Blood Ulmer in 1978, and cameo appearances on Yoko Ono's Plastic Ono Band album (1970), Jamaaladeen Tacuma's Renaissance Man (1983), Joe Henry's Scar (2001) and Lou Reed's The Raven (2003).

In September 2006 he released a live album titled Sound Grammar with his newest quartet (Denardo drumming and two bassists, Gregory Cohen and Tony Falanga). This is his first album of new material in ten years, and was recorded in Germany in 2005. It won the 2007 Pulitzer Prize for music.

Jazz pianist Joanne Brackeen (who had only briefly studied music as a child) stated in an interview with Marian McPartland that Coleman has been mentoring her and giving her semi-formal music lessons in recent years.[9]

Legacy

Coleman continues to push himself into unusual playing situations, often with much younger musicians or musicians from radically different musical cultures, and still performs regularly. An increasing number of his compositions, while not ubiquitous, have become minor jazz standards, including "Lonely Woman," "Peace," "Turnaround," "When Will the Blues Leave?" "The Blessing," "Law Years," "What Reason Could I Give" and "I've Waited All My Life", among others. He has influenced virtually every saxophonist of a modern disposition, and nearly every such jazz musician, of the generation that followed him. His songs have proven endlessly malleable: pianists such as Paul Bley and Paul Plimley have managed to turn them to their purposes; John Zorn recorded Spy vs Spy (1989), an album of extremely loud, fast, and abrupt versions of Coleman songs. Finnish jazz singer Carola covered Coleman's "Lonely Woman" and there have even been progressive bluegrass versions of Coleman tunes (by Richard Greene). Coleman's playing has profoundly influenced, directly or otherwise, countless musicians, trying as he has for five decades to understand and discover the shape of not just jazz, but all music to come.

In 2004 Coleman was awarded The Dorothy and Lillian Gish Prize, one of the richest prizes in the arts, given annually to “a man or woman who has made an outstanding contribution to the beauty of the world and to mankind’s enjoyment and understanding of life.”[10]

On February 11, 2007, Ornette Coleman was honored with a Grammy award for lifetime achievement, in recognition of this legacy.

On July 9, 2009, Ornette Coleman received the Miles Davis Award, a recognition given by the Festival International de Jazz de Montréal to jazz musicians who have contributed along their careers to the evolution of the jazz music.[11][12]

On May 1, 2010, Ornette was awarded a honorary doctorate in Music from the University of Michigan for his musical contributions.[13]

Discography

Notes

- ^ a b c d allmusic Biography

- ^ Spellman, A. B. (1985 originally 1966). Four Lives in the Bebop Business. Limelight. pp. 98–101. ISBN 0-87910-042-7.

- ^ Huey, Steve. "The Shape of Jazz To Come". http://www.allmusic.com/album/r136829.

- ^ "Ornette Coleman biography on Europe Jazz Network". http://www.ejn.it/mus/coleman.htm.

- ^ Rodriguez, Juan (June 20, 2009). "Ornette Coleman, jazz's free spirit". The Montreal Gazette (The Montreal Gazette). http://www.montrealgazette.com/story_print.html?id=1713495&sponsor=. Retrieved 2009-06-29.[dead link]

- ^ Litweiler p.31

- ^ "Ornette Coleman". Last.fm Ltd.. http://www.last.fm/music/Ornette+Coleman. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- ^ Grateful Dead performance 23 Feb 1993 at the Internet Archive

- ^ http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=101558445

- ^ The Dorothy and Lillian Gish Prize, official website.

- ^ Montreal Jazz Festival official page

- ^ http://nouvelles.equipespectra.ca/blog/?p=732&langswitch_lang=en

- ^ http://jazztimes.com/articles/26158-ornette-coleman-awarded-honorary-degree-from-university-of-michigan

References

- Litweiler, John (1992). Ornette Coleman: A Harmolodic Life. London: Quartet Books. ISBN 0704325160

- Coleman, Ornette. Interview with Andy Hamilton. A Question of Scale The Wire July 2005.

- Interview with Eldridge, Roy. Esquire March 1961.

- Jost, Ekkehard (1975). Free Jazz (Studies in Jazz Research 4). Universal Edition.

- Spellman, A. B. (1985 originally 1966). Four Lives in the Bebop Business. Limelight. ISBN 0-87910-042-7.

- Mandel, Howard (2007). Miles, Ornette, Cecil: Jazz Beyond Jazz. Routledge. ISBN 0415967147.

- Christian Broecking (2004). Respekt!. Verbrecher. ISBN 3935843380.

External links

- Official web site

- Concert Photos, Caravan of Dreams, 1985

- Ornette Coleman at Allmusic

- Ornette Coleman discography at MusicBrainz

- Ornette Coleman at the Internet Movie Database

- Article on Coleman's early music

- Interview (1997)

- Interview (1996)

- Interview (1995)

- Interview (1985)

- Ornette: Made in America 1985 documentary about Ornette Coleman directed by Shirley Clarke, re-released on DVD in 2007.

- Tone Dialing: A Conversation on Friendship with Ornette Coleman

- Ornette Coleman tribute by Jazz at Lincoln Center

- Jazz Conversations with Eric Jackson: Ornette Coleman (Part 1) from WGBH Radio Boston

- Jazz Conversations with Eric Jackson: Ornette Coleman (Part 2) from WGBH Radio Boston

Pulitzer Prize for Music (2001–2025) - John Corigliano (2001)

- Henry Brant (2002)

- John Adams (2003)

- Paul Moravec (2004)

- Steven Stucky (2005)

- Yehudi Wyner (2006)

- Ornette Coleman (2007)

- David Lang (2008)

- Steve Reich (2009)

- Jennifer Higdon (2010)

- Zhou Long (2011)

- Complete list

- (1943–1950)

- (1951–1975)

- (1976–2000)

- (2001–2025)

Categories:- 1930 births

- Living people

- Free jazz saxophonists

- Free funk saxophonists

- Avant-garde jazz musicians

- African American musicians

- American jazz saxophonists

- American jazz violinists

- People from Fort Worth, Texas

- Jazz alto saxophonists

- MacArthur Fellows

- Members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters

- Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award winners

- Pulitzer Prize for Music winners

- Atlantic Records artists

- ABC Records artists

- Antilles Records artists

- Blue Note Records artists

- ESP-Disk artists

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.