- Corsican immigration to Puerto Rico

-

Corsican immigration to Puerto Rico

Geographical similarities between both islands

Corsica

Puerto Rico Corsican immigration to Puerto Rico came about as a result of various economic and political changes in the mid-19th century Europe; among those factors were the social-economic changes which came about in Europe as a result of the Second Industrial Revolution, political discontent and widespread crop failure due to long periods of drought, and crop diseases. Another influential factor was that Spain had lost most of its possessions in the so-called "New World" and feared the possibility of a rebellion in its last two Caribbean possessions—Puerto Rico and Cuba. As a consequence the Spanish Crown had issued the Royal Decree of Graces (Real Cedula de Gracias) which fostered and encouraged the immigration of Catholics of non-Hispanic origin to its Caribbean Colonies.

The situation and opportunities offered, plus the fact that the geographies of the islands are similar, were ideal for the immigration of hundreds of families from Corsica to Puerto Rico. Corsicans and those of Corsican descent have played an instrumental role in the development of the economy of the island, especially in the coffee industry.

Contents

19th century Corsica

Corsica is an island located west of Italy and southeast of France. Corsica belonged to the Republic of Genoa (before Genoa became part of Italy) and in 1768 was ceded to France to pay off debt. The island relied largely on its agricultural economy for survival.[1]

Certain changes occurred in Europe during the end of the 18th century and beginning of the 19th century that would greatly affect the lives of the French and the people of Corsica. One of those changes came about with the advent of the Second Industrial Revolution. With the Second Industrial Revolution, many of the people who worked in agriculture began to move to the larger cities with hopes of finding better jobs and better lives. Also, there was a widespread crop failure due to long periods of drought and crop diseases (e.g., the phylloxera epidemic destroyed the Corsican wine industry), cholera epidemic and a general deterioration of economic conditions. Thus, many of the farms in Corsica began to fail.[2]

There was also widespread political discontent characterized by bitter armed conflict. King Louis-Philippe of France was overthrown in the Revolution of 1848 and a republic was declared with a Provisional Government. Three new political groups emerged during that era: they were the liberals, radicals and the socialists. The combination of man-made and natural disasters in Corsica created an acute feeling of hopelessness.[3] All this came about at a time when Spain was growing fearful of the possibility of a rebellion in her Caribbean possessions, which consisted of Puerto Rico and Cuba.

Spanish Royal Decree of Graces

By 1850, Spain had lost the entirety of her territories in South America and Central America and sought measures of preventing a repeat of this in the Caribbean. It was decided that an influx of Catholic immigrants from Ireland, Corsica and Italy would provide a loyal base for the Crown and appeals were made to encourage immigration. In 1815, the Spanish Crown had issued the Royal Decree of Graces (Real Cedula de Gracias) which fostered the immigration of Catholics of non-Hispanic origin to its Caribbean colonies, Puerto Rico and Cuba.[4]

The island of Puerto Rico is very similar in geography to the island of Corsica and therefore appealed to the many Corsicans who wanted to start a "new" life. Under the Spanish Royal Decree of Graces, the Corsicans and other immigrants were granted land and initially given a "Letter of Domicile" after swearing loyalty to the Spanish Crown and allegiance to the Catholic Church. After five years they could request a "Letter of Naturalization" that would make them Spanish subjects.[4]

Influence in coffee industry

Hundreds of Corsicans and their families immigrated to Puerto Rico from as early as 1830, and their numbers peaked in the early 1900s. The first Spanish settlers settled and owned the land in the coastal areas, the Corsicans tended to settle the mountainous southwestern region of the island, primary in the towns of Adjuntas, Lares, Utuado, Ponce, Coamo, Yauco, Guayanilla and Guánica. However, it was Yauco whose rich agricultural area attracted the majority of the Corsican settlers.[5] The three main crops in Yauco were coffee, sugar cane and tobacco. The new settlers dedicated themselves to the cultivation of these crops and within a short period of time some were even able to own and operate their own grocery stores. However, it was with the cultivation of the coffee bean that they would make their fortunes. Cultivation of coffee in Yauco originally began in the Rancheras and Diego Hernández sectors and later extended to the Aguas Blancas, Frailes and Rubias sectors. By the 1860s the Corsican settlers were the leaders of the coffee industry in Puerto Rico and seven out of ten coffee plantations were owned by Corsicans.[6]

The Mariani family of Yauco decided on two courses of action which would strengthen their coffee industry. First, a cotton gin was converted into a machine which was used in dehusking coffee cherries. Second, they sent two of their own as representatives to visit the important European coffee buying centers. The visit to Europe was a success and thus, Puerto Rico became an important member of the worldwide coffee industry.[7]

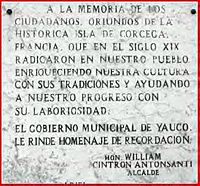

The descendants of the Corsican settlers were also to become influential in the fields of education, literature, journalism and politics. Historian, Colonel Hector A. Negroni, (USAF-Retired), researched the Corsican-Puerto Rican connection and has provided with his work a wealth of information about Puerto Rico's ties with Corsica. Today the town of Yauco is known as both the "Corsican Town" and "The Coffee Town". There's a memorial in Yauco with the inscription, "To the memory of our citizens of Corsican origin, France, who in the C19 became rooted in our village, who have enriched our culture with their traditions and helped our progress with their dedicated work - the municipality of Yauco pays them homage." The Corsican element of Puerto Rico is very much in evidence, Corsican surnames such as Paoli, Negroni and Fraticelli are common.[8]

Landmarks in Yauco

Several properties in Yauco which once belonged to the Corsicans who settled there are registered in the National Register of Historic Places in Puerto Rico.[9]

Casa Franceschi Antongiorgi

The Casa Franceschi Antongiorgi (Franceschi Antongiorgi House) was built in 1907, by the French architect André Troublard, for Alejandro . Franceschi Antongiorgi was a rich landowner and lover of the arts who frequently held banquets, concerts and meetings with visiting artists in his house.[10]

Casa Antonio Mattei Lluberas

The Casa Antonio Mattei Lluberas, also called La Casona Césari (Césari House) was built in 1893 by Antonio Mattei Lluberas. This house is also known as "The House with Twelve Doors." Later, it was acquired by Angel Césari Poggi, husband of Angela Antongiorgi Rodríguez. The Césari–Antongiorgi family was instrumental in the development of the sugar industry in the southern region of the island.[11]

Chalet Amill

The Chalet Amill was built in 1914 by Architect Tomás Olivari Santoni for Ángel Antongiorgi Paoli. Paoli gave the chalet to his daughter Ana Lucía as a wedding gift when she married Juan Amill Rodríguez. The couple soon divorced and by the mid-1920s the chalet was converted into a hotel. First as the Auristela Hotel and then as the Paris Hotel.

Mansion Negroni

The Mansion Negroni (Negroni Mansion), also known as Casa Agostini (Agostini House), was built around 1850 by Antonio Francisco Negroni Mattei. Later it passed to the Agostini Family through the marriage of Maria Victoria Negroni, daughter of Antonio Francisco, and Ignacio Agostini Felipi. . The Agostini family made their fortune in the exportation of coffee. They were the owners of "Sobrinos de Agostini y Compañía" (Nephews of Agostini & Co.). Ángel Pedro Agostini Natali, a member of the family, is credited with inventing the coffee grinder. This machine revolutionized the coffee industry. As a consequence, the island was able to meet the huge demand for Puerto Rican coffee which resulted in the "Golden Age" of Yauco's economy. This house was acquired by the Holy Rosary School in Yauco and a bronze plaque describes its history.[12]

Residencia Lluberas-Negroni

The Residencia Lluberas-Negroni, erroneously called The Residencia González Vivaldi (González Vivaldi Residence) was built in 1880 by Arturo Lluberas for his wife Asuncion Negroni. Most recently, it was acquired by the Gonzalez-Vivaldi Family.

Surnames

The following is an official list of the surnames of the first 403 Corsican families who immigrated to the Adjuntas, Yauco, Guayanilla, and Guanica areas of Puerto Rico in the 19th Century. This list was compiled by genealogist and historian Colonel (USAF Ret. ) Hector A. Negroni who has done exhaustive research on the Corsican migration and origins of his Negroni family name.[13]

Surnames of the first Corsican families in Puerto Rico Adriani, Agostini, Altieri, Anciani, Angilucci, Annoni, Anpani, Antongiorgi, Antoni, Antonini, Antonmarchi, Antonmattei, Antonsanti, Arenas, Artigau, Barbari, Bartoli, Bartolomei, Battistini, Benedetti, Belgodere, Bettolacce, Benvenutti, Berlingeri, Bernardini, Biaggi, Blasini, Boagna, Boccheciamp, Bocagnani, Bonelli, Bonini, Bracetti, Cardi, Carraffa, Casablanca, Casanova, Catinchi, Cervoni, Cesari, Chiavramonti, Cianchini, Costa, Damiani, Dastas, Defendini, Deodati, Dominicci, Emmanuelli, Estella, Fabbiani, Farinacci, Feliberti, Felippi, Ficaya, Figarella, Filipini, Franceschi, Franceshini, Franzuni, Fratacci, Fraticelli, Galletti, Garrosi, Gentili, Gilormini, Giovanetti, Giraldi, Giuseppi, Giuliani, Gordi, Graziani, Grillasca, Grimaldi, Guidiccelli, Lacroix, Lagomarsini, Laveri, Lazarini, Leandri, Linarola, Lipureli, Lorenzi, Lucca, Luchessi, Lucchetti, Luiggi, Maestracci, Malatesta, Marcantoni, Marcucci, Mari, Mariani, Marietti, Marini, Massari, Massei, Masini, Mattei, Maxinie, Micheli, Miguinini, Mignucci, Minucci, Modesti, Molinari, Molinelli, Molini, Montaggioni, Moravani, Mori, Muratti, Natali, Navaroli, Negroni, Nicolai, Nigaglioni, Octaviani, Olivieri, Orsini, Padovani, Paganacci, Palmieri, Paoli, Pelliccia, Pellicer, Piacentini, Piazza, Pieraldi, Piereschi, Pieretti, Pierantoni, Pietrantoni, Pietri, Piovanetti, Poggi, Polidori, Quilinchini, Rafaelli, Rafucci, Rapale, Rencini, Renesi, Romanacce, Romani, Rubiani, Rutali, Safini, Saladini, Sallaveri, Santini, Santoni, Santuchi, Savelli, Semidei, Senati, Shyny, Sinigaglia, Silvagnoli, Silvestrini, Simonetti, Sisco, Sonsonetti, Tollinchi, Tomasi, Tossi, Totti, Vecchini, Vicchioli, Vallevigne, Vicenti, Vincenti, Vincenty, Villanueva, Vivaldi and Vivoni. Distinguished "Yaucano(a)s" of Corsican descent

The following is a list of some of the distinguished natives of Yauco of Corsican descent.[14]

- Agostini, Amelia (1896–1996) – anthologist, poet, educator, professor in Columbia University

- Franquiz, Jose A. (1906–1967) – poet

- Gilormini, Mihiel "Mike" (1918–1988) – World War II hero and Founder of the Puerto Rico Air National Guard. Retired as Brigadier General in the Air National Guard.

- Giovannetti, Jose Antonio – educator, poet

- Mariani, Pedro Domingo (1880–1925) – poet, journalist

- Mariani-Ortiz, Lydia – educator, PR rights activist

- Masini-Molini, Jose Antonio "El Corso" (1913–1987) – Agronomist. Director, Land Authority of P.R. (1969–1972) – Director, Sugar Corporation of P.R. (1977–1984)

- Mattei, Andres (1863–1925) – poet, journalist

- Mattei Lluberas, Antonio (1857–1908) - Leader of the Intentona de Yauco revolt of 1897 and Mayor of Yauco from 1904 to 1906

- Mignucci Calder, Carlos Armando (1889–1954) – politician, Mayor of Yauco (1944–52), Member of Puerto Rico's Constitutional Assembly (1952)

- Negroni, Hector Andres – First Puerto Rican graduate of the US Air Force Academy, US Air Force Colonel, Fighter Pilot, Senior Aerospace Executive and Historian

- Negroni, Julio Alberto – Electrical Engineer who served as the First President for the Water Works Authority in Puerto Rico.

- Negroni, Santiago – journalist, educator and poet

- Negroni Lucca, Santos (1851–1920) – Puerto Rican patriot and one of the 16 prisoners in El Morro Castle in 1887.

- Negroni Mattei, Francisco (1897–1939) – poet, journalist

- Olivari Santoni, Tomás (1902–1904) – Architect and Mayor of Yauco

- Olivieri Rodriguez, Ulises – poet, journalist

- Pietrantoni Blasini, Julio (1935-2006) - lawyer, banker, head of Puerto Rico Government Development Bank from 1978-1985, president of Banco Roig until acquisition by Banco Popular in 1997

- Rojas Tollinchi, Francisco, poet, civic leader and journalist.[15]

- Semidei Rodríguez, José - Brigadier General in the Cuban Liberation Army.

Semidei Rodríguez fought in Cuba's War of Independence (1895–1898) and after Cuba gained its independence he continued to serve in that country as diplomat.[16]

See also

- Corsican people

- List of notable Puerto Ricans

- Royal Decree of Graces of 1815

- Corsican immigration to Venezuela

References

Part of a series on

Puerto Ricans By region or country United States · New York · Hawaii Subgroups African · Chinese · Corsican

French · German · Irish

Jewish · SpanishCulture Art · Cinema · Cuisine · Dance

Education · Flag · Language · Literature · Music · Politics

Sport · TelevisionReligion Roman Catholic · Protestant

Jewish · IslamLanguage Spanish (Castilian) · Accent

VocabularyPuerto Rico portal