- Côa Valley Paleolithic Art

-

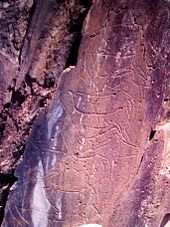

Prehistoric Rock-Art Site of the Côa Valley (Núcleos de arte rupestre do Vale do Côa) Prehistoric art (Arte Rupestre) Animal sketches on the granite stones of the Penascosa Prehistoric SiteOfficial name: Conjunto dos núcleos de arte rupestre do Vale do Côa Country  Portugal

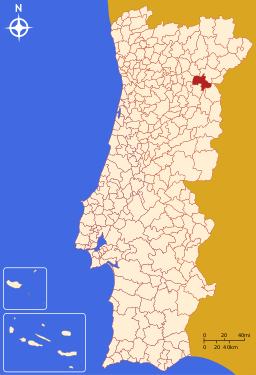

PortugalRegion Norte Sub-region Douro District Guarda Municipality Vila Nova de Foz Côa Length 17,000 m (55,774 ft), South-North Area 200 m2 (2,153 sq ft) Origins Unknown, António Seixas, Alcino Tomé Style Pre-historic Materials Schist, Granite, Ocre/Black paints Origin 22-20,000 years B.C. - Final 17th-20th century - Discovery c. 1990 Owner Portuguese Republic For public Public Visitation Closed (Mondays and on 1 January, Easter Sunday, 1 May and 25 December) UNESCO World Heritage Site Name Prehistoric Rock-Art Sites in the Côa Valley and Siega Verde Year 1998 (#22) Number 866 Region Europe and North America Criteria i, iii Management Instituto Gestão do Patrimonio Arquitectónico e Arqueológico Status National Monument Listing Decree No. 32/97, 2 July 1997 Wikimedia Commons: Conjunto dos sítios arqueológicos no Vale do Rio Côa Website: http://www.arte-coa.pt/ The Côa Valley Paleolithic Art site is an open air sites of Paleolithic art in northeastern Portugal.

In the late 1980s, the engravings were discovered in Vila Nova de Foz Côa. The site in situated in the valley of the Côa River, and comprises thousands of engraved drawings of horses, bovines and other animal, human and abstract figures, dated from 22,000 to 10,000 years BCE. Since 1995 a team of archaeologists have been studying and cataloging this pre-historical complex and a park was created to receive visitors.

Contents

History

Main articles: Prehistoric Iberia and Timeline of Portuguese historyThe first drawings appearing in the Côa Valley date between 22-20,000 years B.C., consisting of zoomorphic imagery of nature.[1] Between 20-18,000 B.C. (Solutense period) a secondary group of animal drawings, included examples of muzzled horses.[1] There was greater elaboration during 16-10,000 years B.C. (Magdalenense period), with a Paleolithic style, with an essentially anthropomorphic and zoomorphic designs that included horses with their characteristic manes, aurochs with mouths and nostrils and deer.[1]

There were further paintings dating back to the Epipaleolithic period of zoomorphic semi-naturalist design.[1] Another phase of anthropomorphic designs were encountered during the Neolithic, that included also included zoomorphic designs that were both geometric and abstract.[1] Anthropomorphic designs also appeared dating back to the Chalcolithic and Bronze Ages that were primarily anthropomorphic in character.[1]

Between the 5th and 1st centuries early organized humans were responsible for anthropomorphic and zoomorphic designs that included weapons and symbols.[1]

The final era of recorded rock art, corresponding to the 17th to 20th century, that include religious, anthropomorphic and zoomorphic designs, inscriptions and dates. The later part of these designs include representations of boats, trains, bridges, planes and representations of various scenes, including drawings completed by António Seixas and Alcino Tomé.[2][3]

20th century

In the 20th century, the construction of the Pocinho Dam likely resulted in the immersion of many rock cliff drawings.[4]

By the 1990s, prospectors revealed a group of important Paleolithic, Neolithic and Chalcolithic carvings in the lower part of the Côa Valley, likely in November 1991 by Nelson Rabanda (but which were only publihsed in November 1994).[5][6][4] Later, António Martinho Baptista would determine that Iron Age carvings corresponded to Celtic-Iberian tribes, specifically the Medobrigenais or Zoilos.[4] Some of the peoples identified, from this period, had not already been identified in other archaeological investigations.[3]

In 1995, a plan to construct a dam was approved and principal work began in the Côa Valley.[4] But, following the original discovery of rock art, an archaeologist had been investigating the kilometres long Côa valley under the direction of the national Portuguese energy producer (Energias de Portugal - EDP) and the agency responsible for monitoring architectural patrimony (Instituto Português do Património Arquitectónico - IPPAR).[4] Both agencies were aware of the prehistoric art along the Côa, much earlier then the general public and scientific community were informed.[4] Archaeologist Nélson Rabanda, studying the site under an agreement between EDP and IPPAR, reported the case to the press, as well as other organizations interested in prehistoric art and patrimony, such as UNESCO.[7][4] There was an immediate move by EDP to disprove the age of the carvings, and thus continue their dam project.[4]

The local scandal forced IPPAR to petition UNESCO for a review of the site, and Jean Clottes in December 1994 came to the region to investigate the discoveries. But, the UNESCO reports were not unanimous about whether or not the power plant should be built; Clottes, the head of prehistoric department, noted that rising water may protect the engravings from vandalism, but also confirmed that Coa Valley "is the biggest open air site of palaeolithic art in Europe, if not in the world".[4] At the time, the number of carvings were limited and many suspected that many more had already been submerged by the previous Pocinho Dam project.[4] This was proven by Nelson Rabanda who investigated the submerged Canada do Inferno site, finding several other examples. With little input from the national government on its status it came to invading archaeologists to finally discover other sites in the areas of Penascosa, Ribeira de Riscos, Quinta da Barca, Vermelhosa, Vale de José Esteves, among others, who quickly published their discoveries or promoted them on national media networks.[4] A citizens group Movimento para a Salvação das Gravuras do Côa quickly appeared with their slogan "As gravuras não sabem nadar" (The carvings can't swim), which they plasterd on the side of the local secondary school.[8]

A second UNESCO team, lead by Mounir Bouchenaki, director of the World Heritage branch, was sent to definitively conclude the case: his team determined that a great part of the carvings dated as far back as the Palaeolithic.[9] The dam construction led to a scandal within Portuguese government and pressure from the international community, with the project being denounced in newspapers like The Sunday Times, The New York Times and International Herald Tribune, as well as in the public broadcasters such as BBC.[9]

Meanwhile, after the visit of the UNESCO delegation, the IPPAR created an international scientific commission to accompany the study of the art in the Côa valley: a move that was controversial.[9] It included António Beltrán, E. Anati and Jean Clottes, and met on time in May 1994, while EDP continued to promote other methods of "saving" the prehistoric art (such as creating moulds or carving the panels from the cliff faces), while still promoting the continuation of the dam project.[9] EDP was also helped by the direct dating controversy; Robert Bednarik and Alan Watchman, in addition to Fred Phillips and Ronald Dorn, used an unproven methodology to affirm that the carvings were not Palaeolithic.[9] These events did not please the archaeologists and the public, and a NIMBY movement towards the dam developed, which could only be resolved through a complete change in political thinking.[9] This occurred with the 1995 Legislative elections that saw a change in government; under Prime Minister António Guterres the dam project was cancelled in November 1995.[9]

A system of monitorization and conservation was established to protect the remnants; the events of the "Battle of Côa" were responsible for the constitution on May 1997, by the Ministry of Culture (Portuguese: Ministério da Cultura), the Portuguese Institute of Archaeology (Portuguese: Instituto Português de Arqueologia, as well as the dependent agencies, the National Centre for Prehistoric Art (Portuguese: Centro Nacional de Arte Rupestre (CNART)), the Archaeological Park of the Côa Valley (Portuguese: Parque Arqueológico do Vale do COa (PAVC)), and the National Centre for Aquatic and Subaquatic Archaeology (Portuguese: Centro Nacional de Arqueologia Náutica e Subaquática (CNANS)), was opened in August 1996, without legal authority.[10][9]

The Prehistoric Rock-Art Sites in the Côa Valley were designated a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1998 (from an advisory board report on 25 June 1997).[11][12][9]

In 2003, a study was begun to study the viability of introducing the Prewzalski species of horse, equivalent to those characterized in the Paleolithic rock art.[13]

By May 2004, a public tender was commissioned by the Portuguese Order of Architects to design the Côa Museum (it was won by architects Tiago Pimentel and Camilo Rebelo). It was followed by a competition to construct the museum. On 26 January 2007, the Côa Museum construction was started with the placing of the first cornerstone by Minister of Culture, Isabel Pires de Lima, and work initiated by Monte Adiano.

Formal excavations began in Fariseu on 19 September 2005, completed in October, under the direction of Thierry Aubry, which discovered several slabs of schist (10 x 20 centimetres) dating to the Paleolithic.

The conference HERITAGE 2008 - World Heritage and Sustainable Development International Conference took place at Vila Nova de Foz Côa between 7–9 May 2008.[14] The conference was conceived to examine the relationships between heritage and human development, and the natural environment and building preservation, and promoted significant discussion, organized by the Portuguese Ministry of Culture (Portuguese: Ministério da Cultura).

In August 2010, the World Heritage Committee extended the UNESCO world heritage extension to neighbouring site of Siega Verde in Spain.[10] The Siega Verde Archaeological, with comparable carvings/etchings in 94 panels along a 15 kilometre stretch across the border includes over 500 representations. Its dating to the similar period, allowed its inclusion in the world designation with the Côa Valley sites.[10]

Geography

The prehistoric site can be accessed from EN102 motorway (Vila Nova de Foz Côa-Celorico da Beira), via Muxagata, or alternately via the EN222 motorway (Vila Nova de Foz Côa-Figueira de Castelo Rodrigo) detouring from Castelo Melhor. The territory includes parts of the municipalities of Figueira de Castelo Rodrigo, Mêda, Pinhel and Vila Nova de Foz Côa.

The lower portion of Côa River Valley runs south to north, at about 130 metres above sea level, spread over an area of 17 km (10.56 mi) of the lower Côa river valley. The watercourse is flanked by rolling/undulating hills, surrounded by rare species of river brush, vineyards, olive and almond trees, with the higher elevations occupied by pasturelands and fields. At about the 17 kilometre mark, there relief is rocky with granite and schist outcroppings common.

The Prehistoric Rock Art Sites of the Côa Valley are actually 23 sites with engravings or paintings, along the last 17 kilometres of the River Côa (with ten sites located along the left bank and eight on the right bank of the river). In addition five sites are located along the tributaries along the Douro River, constituted into three different nuclei: Faia, Quinta da Barca and Penacosa, along the mouth of the Ribeira de Piscos, in an area of 20,000 hectares.

Of the 23 archaeological sites, 14 are classified:

- Prehistoric Rock-Art Site of Broeira (Vila Nova de Foz Côa)

- Prehistoric Rock-Art Site of Canada do Inferno/Rego da Vide (Vila Nova de Foz Côa)

- Prehistoric Rock-Art Site of Faia (Pinhel)

- Prehistoric Rock-Art Site of Faia/Vale Afonsinho (Figueira de Castelo Rodrigo)

- Prehistoric Rock-Art Site of Fonte Frieira (Vila Nova de Foz Côa)

- Prehistoric Rock-Art Site of Meijapão (Vila Nova de Foz Côa)

- Prehistoric Rock-Art Site of Penascosa (Vila Nova de Foz Côa)

- Prehistoric Rock-Art Site of Quinta da Barca (Vila Nova de Foz Côa)

- Prehistoric Rock-Art Site of Quinta do Fariseu (Vila Nova de Foz Côa)

- Prehistoric Rock-Art Site of Ribeirinha (Vila Nova de Foz Côa)

- Prehistoric Rock-Art Site of Ribeira de Piscos/Quinta dos Poios (Vila Nova de Foz Côa)

- Prehistoric Rock-Art Site of Vale da Figueira/Teixugo (Vila Nova de Foz Côa)

- Prehistoric Rock-Art Site of Vale de Moinhos (Vila Nova de Foz Côa)

- Prehistoric Rock-Art Site of Vale dos Namorados (Vila Nova de Foz Côa)

Nine sites are in the process of achieving classification:

- Alto da Bulha

- Canada da Moreira

- Moinhos de Cima

- Vale de Cabrões

- Vale da Casa

- Vale de Forno

- Vale de José Esteves

- Vale de Videiro

- Vermelhosa

Art

The prehistoric art is either carved, incised or picked, combining various techniques, but rarely painted, utilizing the vertical schist slabs as canvass. These schist rocks, along the northern part of the Côa River, are large drawings in contrast with smaller depictions in other parts of the region.[3][1] Their size vary between 15 cm (5.91 in) and 180 cm (70.87 in), but most are 40-50 centimetres in extension, often forming panels and compositions.[3] The style often features bold lines, but many are touched with fine, thin lines.[1]

The art near Faia, occupies several vertical panels of granite. Two groups of authors were identified in this region, comprising 230 carvings from the Epipaleolithic and Bronze Ages.[3] The more archaic period of Côa corresponds to 137 rocks with 1000 carvings and rare paintings, by artists who concentrated on zoomorphic representations: equine (horses), bovine (aurochs), caprines and deer (the latter primarily associated with the final phase of the Magdalense period).[3][1] There are also representations of fish, intermediary animals, along with a small group of geometric or abstract shapes (including lines and symbols in Penascosa and Canada do Inferno).[3][1]

In one of the rarer depictions, there is a solitary anthropomorphic figure with phallus, dating to the Magdalenense period in the Ribeira de Piscos site.[3] The artists motives are unclear, and the image appears isolated and over-drawn by other figures.[3]

At the Rock Art Site of Faia, there are unique painted carvings, with ocre paint tracing the image and highlighting the nostrals and mouth of the figure.[3] Other groups of carvings in Vale Carbões and Faia, dating from the Epipaleolithic and Neolithic, include zoomorphic designs, also painted with ocre.[3]

There are also, Iron Age sites along the mouth of the Côa, in the valleys of the smaller ravine tributaries of the Douro.[3] They include anthropomorphic figures and horses, in addition to some dogs, deer and birds, accompanied by weapons (swords, lances and shields).[3] These armed warriors could represent scenes from battles or hunting parties. Generally, these images are stratified, with new designs drawn over the pre-existing carvings.[15][3]

The last period of art dates from the modern era, and includes religious motifs, both anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figures, in addition to inscriptions, dates, boats, trains, bridges, planes and landscapes.[3]

The importance of this prehistorical art site remains its rareness and extension; although there are numerous prehistorical art sites in caves, open-air sites are rarer (and only include Mazouco (Portugal), Fornols-Haut (France), Domingo García and the Siega Verde (both in Spain). Yet, the importance of the Côa Valley is the extent of these designs, which extend sporadically in a space 17 kilometres. Archaeologists acknowledge sites like this as open-air sanctuaries of prehistoric humankind.

References

- Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k António Martinho Baptista and Mário Varela Gomes (1995), p.350-384

- ^ Baptista (1999)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o CNART (1999)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k António Martinho Baptista (2002), p.62

- ^ Nelson Rebanda (1995)

- ^ António Faustino de Carvalho (1995)

- ^ Nelson Rebanda (1995)

- ^ António Martinho Baptista (2002), p.62-63

- ^ a b c d e f g h i António Martinho Baptista (2002), p.63

- ^ a b c IGESPAR, ed (2011). "Prehistoric Rock Art Sites in the Côa Valley and Siega Verde". Lisbon, Portugal: IGESPAR - Instituto de Gestão do Património Arquitectónico e Arqueológico. http://www.igespar.pt/en/patrimonio/mundial/portugal/117/. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- ^ UNESCO, ed. (25 June 1997), "Advisory Body Evaluation (1998)", World Heritage Committee Session, Paris, France: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, http://whc.unesco.org/archive/advisory_body_evaluation/866.pdf, retrieved 1 August 2911

- ^ UNESCO, ed. (29 January 1999), "Report of the Committee", Convention Concerning the Protection of the World and Natural Heritage, Paris, France: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, http://whc.unesco.org/archive/repcom98.htm#866, retrieved 1 August 2911

- ^ Fatima Monteiro (11 January 2006)

- ^ UNESCO, ed. Heritage Events "HERITAGE 2008- World Heritage and Sustainable Development International Conference". United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. http://whc.unesco.org/en/events/431World Heritage Events. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- ^ Baptista (1999)

- Sources

- Rebanda, Nelson (1995) (in Portuguese), Os trabalhos arqueológicos e o complexo de arte rupestre do Côa, Lisbon, Portugal

- Baptista, António Martinho; Gomes, Mário Varela (1995) (in Portuguese), Arte rupestre do vale do Côa. Canada do Inferno. Primeiras impressões, Trabalhos de Antropologia e Etnologia, Porto, Portugal, pp. 349–385

- Baptista, António Martinho; Gomes, Mário Varela (1996) (in Portuguese), Arte rupestre do vale do Côa. (Fichas interpretativas Canada do Inferno e Penascosa), Lisbon, Portugal

- Carvalho, António Faustino de; Zilhão, João; Aubry, Thierry (1996) (in Portuguese), Lisbon, Portugal

- Zilhão, João (1997) (in Portuguese), Arte rupestre e pré-história do vale do Côa. Trabalhos de 1995-1996, Lisbon, Portugal

- UNESCO, ed. (25 June 1997), "Advisory Body Evaluation (1998)", World Heritage Committee Session, Paris, France: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, http://whc.unesco.org/archive/advisory_body_evaluation/866.pdf, retrieved 1 August 2911

- UNESCO, ed. (29 January 1999), "Report of the Committee", Convention Concerning the Protection of the World and Natural Heritage, Paris, France: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, http://whc.unesco.org/archive/repcom98.htm#866, retrieved 1 August 2911

- Baptista, António Martinho (1998) (in Portugese), Arte rupestre do vale do Côa. (Fichas interpretativas Canada do Inferno, Penascosa e Piscos), Lisbon, Portugal

- Baptista, António Martinho (1999) (in Portuguese), A Arte dos caçadores paleolíticos do vale do Côa, Vila Nova de Foz Côa, Portugal

- CNART, ed. (1999) (in Portuguese), Inventário da arte rupestre do Vale do Côa, Vila Nova de Foz Côa, Portugal: CNART - Centro Nacional de Arte Rupestre

- Baptista, António Martinho (2001), A Arte Rupestre e o Parque Arqueológico do Vale do Côa. Um exemplo de estudo e salvaguarda do património rupestre pré-histórico em Portugal, Donostia, Spain: XV Congreso de Estudios Váscos: Ciencia y cultura vasca. y redes telemáticas, pp. 61–67, ISBN 84.8419-949-5, http://www.arte-coa.pt/Ficheiros/Bibliografia/1242/1242.pt.pdf

- "Descoberto novo núcleo de pinturas rupestres em Foz Côa" (in Portuguese), O Primeiro de Janeiro, 15 October 2005

- "Arte Rupestre Móvel no Côa" (in Portuguese), Jornal de Notícias, 16 Outubro 2005

- Amaral, Deus (19 October 2005), "A polémica do Fariseu" (in Portuguese), Nova Guarda

- "Descoberto maior conjunto móvel do Paleolítico" (in Portuguese), Terras da Beira, 20 October 2005

- "Maior conjunto de arte móvel do Paleolítico no Vale do Côa" (in Portuguese), O Interior, 20 October 2005

- "Vale do Côa - descoberto conjunto de arte do Paleolítico" (in Portuguese), Jornal do Fundão, 21 October 2005

- "Parque Arqueológico do Vale do Côa vai finalmente ser criado" (in Portuguese), Público, 26 December 2005

- Gonçalves, Elisabete (29 December 2005), "Foz Côa - Parque Arqueológico criado em 2006" (in Portuguese), Terras da Beira

- "Parque Arqueológico do Vale do Côa para breve" (in Portuguese), O Interior, 29 December 2005

- Sanchez, Paula (2 January 2006), "Vale do Côa com dez anos de estagnação" (in Portuguese), Diário de Notícias

- "Museu do Côa tem de ficar concluído antes de 2008" (in Portuguese), Notícias da Covilhã, 6 January 2006

- Monteiro, Fátima (11 January 2006), "Cavalo Prewzalski semelhante aos modelos gravados no Vale do Côa" (in Portuguese), Nova Guarda

- "Museu do Côa pronto em 2008" (in Portuguese), Expresso, 4 March 2006

- "Museu abre em final de 2008" (in Portuguese), O Primeiro de Janeiro, 15 March 2006

- "Museu do Côa: a grande pedra entre uma paisagem intocada" (in Portuguese), Diário de Notícias, 16 March 2006

- "Museu prometido há quase huma década, abre no final de 2008" (in Portuguese), Jornal do Fundão, 16 Março 2006

- "Gravuras indiciam que houve uma escola de arte rupestre" (in Portuguese), Diário de Notícias, 18 March 2006

- "Parque do Côa ainda não é zona protegida" (in Portuguese), Expresso, 18 March 2006

- "Espanhóis a postos de tirar partido de Foz Côa" (in Portuguese), Ecos da Marofa, 10 Maio 2006

- "Foz Côa nunca existiu" (in Portuguese), Expresso, 5 August 2006

- "Vale do Côa 10 anos de património arqueológico" (in Portuguese), Nova Guarda, 9 August 2006

- "Foz Côa - Parque Arqueológico, 10 anos depois, atrai pouca gente" (in Portuguese), Notícias da Covilhã, 17 August 2006

- Gonçalves, Maria Eduarda (20 September 2006), "Foz Côa: um debate interminável" (in Portuguese), Diário Económico

- "Museu do Côa pode ser uma realidade a curto prazo" (in Portuguese), Nova Guarda, 11 Outubro 2006

- Cordeiro, Ricardo (14 October 2006), "Gravuras do Côa bem abrigadas" (in Portuguese), Expresso

- "Museu de Arte e Arqueologia começou a ser construído" (in Portuguese), Notícias da Manhã, 10 January 2007

- Cristino, Pedro (26 January 2007), "Obras arrancam em Vale do Côa" (in Portuguese), Construir

- "Primeira pedra lançada hoje" (in Portuguese), Jornal de Notícias, 26 Janeiro 2007

See also

- Timeline of Iberian prehistory

External links

- IGESPAR - Côa Valley Archaeological Park

- Paleolithic Art in the Côa Valley - Institute of Archaeology, University of Coimbra

- HERITAGE 2008 - World Heritage and Sustainable Development International Conference

World Heritage Sites in Portugal Norte Alto Douro Wine Region · Historic Centre of Guimarães · Historic Centre of Porto · Prehistoric Rock-Art Sites in the Côa Valley and Siega Verde1

Centro Lisboa Cultural Landscape of Sintra · Monastery of the Hieronymites and Belém Tower, Lisbon

Alentejo Historic Centre of Évora

Azores Madeira Categories:- Prehistoric sites in Portugal

- Paleolithic

- Prehistoric art

- World Heritage Sites in Portugal

- National monuments in Portugal

- Rock art in Europe

- Petroglyphs

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.