- April Fools' Day

-

This article is about the informal holiday. For other uses, please see April Fool's Day (disambiguation) or April Fool.

April Fools' Day

An "April Fool" hoax in Copenhagen, Denmark in 2001, featuring its new metroAlso called All Fools' Day Type Cultural, western Significance Practical pranks Date April 1 Observances Humor April Fools' Day is celebrated in different countries around the world on April 1 every year. Sometimes referred to as All Fools' Day, April 1 is not a national holiday, but is widely recognized and celebrated as a day when many people play all kinds of jokes and foolishness. The day is marked by the commission of good-humoured or otherwise funny jokes, hoaxes, and other practical jokes of varying sophistication on friends, family members, teachers, neighbors, work associates, etc.

Traditionally, in some countries such as Canada, New Zealand, the UK, Cyprus, and South Africa, the jokes only last until noon, and someone who plays a trick after noon is called an "April Fool" and taunted "April Fool's Day's past and gone, You're the fool for making one."[1] Elsewhere, such as in France, Italy, South Korea, Japan, Russia, The Netherlands, Germany, Brazil, Ireland, Australia, and the U.S., the jokes last all day. In France children put paper fish on each others back as a trick and would shout "poisson d'avril!"

The earliest recorded association between April 1 and foolishness can be found in Chaucer's Canterbury Tales (1392). Many writers suggest that the restoration of January 1 as New Year's Day in the 16th century was responsible for the creation of the holiday, but this theory does not explain earlier references.

Contents

Origins

Precursors of April Fools' Day include the Roman festival of Hilaria, held March 25,[2] and the Medieval Festival of Fools, held December 28,[3] still a day on which pranks are played in Spanish-speaking countries.

In Chaucer's Canterbury Tales (1392), the "Nun's Priest's Tale" is set Syn March bigan thritty dayes and two.[4] Modern scholars believe that there is a copying error in the extant manuscripts and that Chaucer actually wrote, Syn March was gon.[5] Thus the passage originally meant 32 days after March, i.e. May 2,[6] the anniversary of the engagement of King Richard II of England to Anne of Bohemia, which took place in 1381. Readers apparently misunderstood this line to mean "March 32", i.e. April 1.[7] In Chaucer's tale, the vain cock Chauntecleer is tricked by a fox.

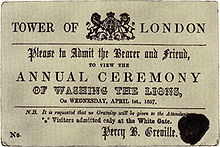

In 1508, French poet Eloy d'Amerval referred to a poisson d’avril (April fool, literally "April fish"), a possible reference to the holiday.[8] In 1539, Flemish poet Eduard de Dene wrote of a nobleman who sent his servants on foolish errands on April 1.[6] In 1686, John Aubrey referred to the holiday as "Fooles holy day", the first British reference.[6] On April 1, 1698, several people were tricked into going to the Tower of London to "see the Lions washed".[6]

In the Middle Ages, New Year's Day was celebrated on March 25 in most European towns.[9] In some areas of France, New Year's was a week-long holiday ending on April 1.[2][3] Many writers suggest that April Fools originated because those who celebrated on the January 1 made fun of those who celebrated on other dates.[2] The use of the January 1 as New Year's Day was common in France by the mid-16th century,[6] and this date was adopted officially in 1564 by the Edict of Roussillon.

Other prank days in the world

Iranians play jokes on each other on the 13th day of the Persian new year (Norouz), which falls on April 1 or April 2. This day, celebrated as far back as 536 BC[citation needed], is called Sizdah Bedar and is the oldest prank-tradition in the world still alive today; this fact has led many to believe that April Fools' Day has its origins in this tradition.[10]

The April 1 tradition in France and French-speaking Canada includes poisson d'avril (literally "April's fish"), attempting to attach a paper fish to the victim's back without being noticed. This is also widespread in other nations, such as Italy, where the term Pesce d'aprile (literally "April's fish") is also used to refer to any jokes done during the day. In Spanish-speaking countries, similar pranks are practiced on December 28, día de los Santos Inocentes, the "Day of the Holy Innocents". This custom also exists in certain areas of Belgium, including the province of Antwerp. The Flemish tradition is for children to lock out their parents or teachers, only letting them in if they promise to bring treats the same evening or the next day.

Under the Joseon dynasty of Korea, the royal family and courtiers were allowed to lie and fool each other, regardless of their hierarchy, on the first snowy day of the year. They would stuff snow inside bowls and send it to the victim of the prank with fake excuses. The recipient of the snow was thought to be a loser in the game and had to grant a wish of the sender. Because pranks were not deliberately planned, they were harmless and were often done as benevolence towards royal servants.[citation needed]

In Poland, prima aprilis ("April 1" in Latin) is a day full of jokes; various hoaxes are prepared by people, media (which sometimes cooperate to make the "information" more credible) and even public institutions. Serious activities are usually avoided. This conviction is so strong that the anti-Turkish alliance with Leopold I signed on April 1, 1683, was backdated to March 31.

In Scotland, April Fools' Day is traditionally called Hunt-the-Gowk Day ("gowk" is Scots for a cuckoo or a foolish person), although this name has fallen into disuse. The traditional prank is to ask someone to deliver a sealed message requesting help of some sort. In fact, the message reads "Dinna laugh, dinna smile. Hunt the gowk another mile". The recipient, upon reading it, will explain he can only help if he first contacts another person, and sends the victim to this person with an identical message, with the same result.[11]

In Denmark, May 1 is known as "Maj-kat", meaning "May-cat", and is also a joking day. May 1'st is also celebrated in Sweden as an alternative joking day. When someone has been fooled in Sweden, to disclose that it was a joke, the fooler says the rhyme "April April din dumma sill, jag kan lura dig vart jag vill" (April, April, you stupid herring, I can fool you to wherever I want") for April 1st jokes, or "Maj maj måne, jag kan lura dig till Skåne" (May May moon, I can fool you into Scania) for May 1st jokes. Both Danes and Swedes also celebrate April Fools' Day ("aprilsnar" in Danish). Pranks on May 1, are much less frequent.

In Spain and Ibero-America, an equivalent date is December 28, Christian day of celebration of the Massacre of the Innocents. The Christian celebration is a holiday in its own right, a religious one, but the tradition of pranks is not, though the latter is observed yearly. After somebody plays a joke or a prank on somebody else, the joker usually cries out, in some regions of Ibero-America: "Inocente palomita que te dejaste engañar" ("You innocent little dove that let yourself be fooled"). In Spain, it is common to say just "Inocente!" ("Innocent!"). Nevertheless, in the Spanish island of Menorca, "Dia d'enganyar" ("Fooling day") is celebrated on April 1 because Menorca was a British possession during part of the 18th century.[citation needed]

See also

- April Fool is the codename for a spy and double agent who allegedly played a key role in the downfall of the Iraqi President Saddam Hussein.

- April Fools' Day RFC

- Edible Book Day

- Fools Guild, entertainment troupe which holds a party in Los Angeles every April Fool's Day

- Fossil Fools Day

- Google's hoaxes

- Jafr alien invasion

- List of April Fool's Day jokes

- Pigasus Award, a tongue-in-cheek honour presented on April 1 in the field of "Paranormal fraud".

- Sizdah Bedar, the last day of two-week springtime celebrations for the Persian New Year is a day of pranks, very similar to April Fools' Day.

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Opie, Iona & Peter (1967). The Lore and Language of Schoolchildren.. Oxford: OUP. pp. 246–247. ISBN 0-19-282059-1.

- ^ a b c April Fools' Day, Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ a b Santino, Jack, All around the year: holidays and celebrations in American life, p. 97, 1972.

- ^ The Canterbury Tales, "The Nun's Priest's Tale" - "Chaucer in the Twenty-First Century", University of Maine at Machias, September 21, 2007

- ^ Carol Poster, Richard J. Utz, Disputatio: an international transdisciplinary journal of the late middle ages, Volume 2, pp. 16-17 (1997).

- ^ a b c d e Boese, Alex (2008) "April Fools Day - Origin " Museum of Hoaxes

- ^ Compare to Valentine's Day, a holiday that originated with a similar misunderstanding of Chaucer.

- ^ Eloy d'Amerval, Le Livre de la Deablerie, Librairie Droz, p. 70. (1991). "De maint homme et de mainte fame, poisson d'Apvril vien tost a moy."

- ^ Groves, Marsha, Manners and Customs in the Middle Ages, p. 27, 2005.

- ^ "The History of April Fools' Day". Life123. http://www.life123.com/holidays/more-holidays/april-holidays/the-history-of-april-fools-day.shtml. Retrieved March 31, 2011.

- ^ Opie, Iona & Peter (1967). The Lore and Language of Schoolchildren. Oxford: OUP. pp. 246–247. ISBN 0-19-282059-1.

External links

- April Fools' Day On The Web: The most complete listing of April Fools' Day Jokes that Web Sites have run each year from 2004 all the way until the present

- Museum of Hoaxes: Top 100 April Fools' Day hoaxes of all time

- Top 100 April Fools Pranks and Gadgets

Non-holiday traditions in the United States Inauguration Day • Super Bowl Sunday • March Madness • Super Tuesday • April Fools' Day • Opening Day • Tax Day • Oktoberfest • World Series • Election Day • Black Friday • Cyber MondayCategories:- April Fools' Day

- April observances

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.