- Martin Chuzzlewit

-

Martin Chuzzlewit

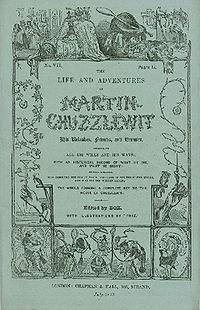

Cover, first serial edition seventh installment, July 1843Author(s) Charles Dickens Original title The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit Illustrator Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz) Country England Language English Series Monthly: January 1843 - July 1844 Genre(s) Novel

Social criticismPublisher Chapman & Hall Publication date 1844 Media type Print (Serial, Hardback, and Paperback) Preceded by American Notes Followed by A Christmas Carol The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit (commonly known as Martin Chuzzlewit) is a novel by Charles Dickens, considered the last of his picaresque novels. It was originally serialized between 1843-1844. Dickens himself proclaimed Martin Chuzzlewit to be his best work, but it was one of his least popular novels.[1] Like nearly all of Dickens' novels, Martin Chuzzlewit was released to the public in monthly instalments. Early sales of the monthly parts were disappointing, compared to previous works, so Dickens changed the plot to send the title character to America. This allowed the author to portray the United States (which he had visited in 1842) satirically as a near wilderness with pockets of civilization filled with deceptive and self-promoting hucksters.

The main theme of the novel, according to a Preface by Dickens, is selfishness, portrayed in a satirical fashion using all the members of the Chuzzlewit family. The novel is also notable for two of Dickens' great villains, Seth Pecksniff and Jonas Chuzzlewit. It is dedicated to Angela Georgina Burdett-Coutts, a friend of Dickens.

The novel was adapted into a television mini series in 1994.

Contents

Plot summary

Young Martin Chuzzlewit was raised by his grandfather and namesake. The senior Martin, a very wealthy man, has been long convinced that everyone around him is after his money, and so takes the precaution, years before the book begins, of raising an orphaned girl, Mary, to be his nursemaid, with the understanding that she would be well cared for as long as he lived, but upon his death be thrown out onto the streets, penniless. She would thus have great motivation to care for his well-being and safeguard him from harm, in contrast to his relatives, who want him to die. However, his grandson and heir, Martin, falls in love with Mary and wishes to marry her, ruining the senior Martin's plans to keep her uninterested in his fortune. He demands his grandson give up the engagement, but the latter refuses, prompting his grandfather to disinherit him.

Young Martin decides to sign on as an apprentice to Mr. Pecksniff, a talentless, greedy, pseudo-pious poseur who periodically takes in students to teach them architecture, while actually teaching them nothing, treating them badly, living grandly off their tuition fees, and having them do draughting work that he passes off as his own. He has two vain, spoiled, mean-spirited and pseudo-pious daughters, Mercy (Merry) and Charity (Cherry). Unbeknown to young Martin, Mr. Pecksniff, also a relative of Chuzzlewit, has actually taken the grandson on in order to establish closer ties with the wealthy grandfather, thinking that the grandfather's gratitude will gain Pecksniff a prominent place in the will.

While with the Pecksniffs, the younger Martin meets and befriends Tom Pinch, who is in some ways the true protagonist of the novel. Pinch is a gentle, kind-hearted soul whose late grandmother had given Pecksniff all she had, believing Pecksniff would make a grand architect and gentleman of him. Pinch is so virtuous that he is incapable of believing any of the bad things others tell him of Pecksniff, and always defends him vociferously. He also has a sister who is a governess in London. Pinch works for Pecksniff for exploitatively low wages, all the while believing that he is the unworthy recipient of Pecksniff's charity. As the novel opens, we briefly meet John Westlock, Pecksniff's student, who sees the value of Pinch and the evil of Pecksniff, and parts ways from the household.

When Grandfather Chuzzlewit hears of his grandson's new life, he demands that Mr. Pecksniff kick the penniless young Martin out, which Pecksniff promptly does. Then, the senior Martin moves in with Mr. Pecksniff and slowly appears to fall under his complete control. During this sojourn, Pinch falls in love with Mary, but does not declare his love, knowing of her attachment to the young Martin.

One of Martin senior's greedy relatives is his brother, Anthony Chuzzlewit, who is in business with his son, Jonas. While somewhat affluent themselves, they live miserly, cruel lives, with Jonas constantly berating his father, eager for the old man to die so he can get control of his inheritance. Anthony dies abruptly and under suspicious circumstances, leaving his wealth to Jonas. Jonas then woos Cherry Pecksniff, who is very flattered and receptive to his attentions, while insulting and arguing constantly with Merry, whom he refers to simply as "the other one." He then abruptly and cruelly declares to Seth Pecksniff that he wants to marry Merry, and jilts a furious Cherry. During their courtship, Merry continues to tease and abuse Jonas verbally, enjoying her power over him. He in turn responds to this teasing affably, muttering that he will get his revenge once they are married. This indeed happens: after their marriage, he seriously physically and emotionally abuses Merry. Her personality changes from that of a giggly, flighty girl to a crushed and frightened woman. Cherry delights in Merry's pain.

Jonas, meanwhile, becomes entangled with the unscrupulous Montague Tigg and joins in his pyramid scheme-like insurance scam. Introduced at the beginning of the book as Montague Tigg, he is a dirty, petty thief and hanger-on of a Chuzzlewit relative, Chevy Slyme. Tigg has changed his name to Tigg Montague and transformed himself into a seemingly fine man after cheating the young Martin Chuzzlewit out of a valuable pocket-watch. He uses the funds from the watch to buy fine clothes, rent a distinguished-looking office, and purchase other false signs of success and good breeding. This façade is enough to convince investors that he must be an important businessman from whom they may greatly profit.

At this time, Tom Pinch, after years of devoted service, finally comes to see his employer's true character when Mary tells him of Mr. Pecksniff's unwanted advances and mistreatment of her. Pecksniff, having overheard the conversation between Tom and Mary, falsely accuses Tom and demands his resignation. Pinch goes to London to seek employment, and rescues his governess sister Ruth, whom he discovers has been mistreated by the snobbish family employing her. The two set up housekeeping together. He renews his friendship with John Westlock, who has recently come into an inheritance. Pinch quickly receives an ideal job from a mysterious employer, with the help of an equally mysterious Mr. Fips.

Young Martin, meanwhile, has fallen in with Mark Tapley, a kind man from the inn in the town where Pecksniff lives. Mark, a satirical character, is always affable and cheerful, which he decides does not reflect well on him because he is always in happy circumstances and it shows no strength of character to be happy when one has good fortune. He decides he must test his cheerfulness by seeing if he can maintain it in the worst circumstances possible. To this end, he decides to accompany young Martin Chuzzlewit as his unpaid servant (indeed, he uses up his life savings paying for things for Martin) as he makes his way to the United States to seek his fortune. The men travel to America, and then attempt to start new lives in a swampy, disease-filled settlement named "Eden" by the corrupt hucksters who sell him land there. Dickens uses the scenes set in America to make many humorous observations about the generally low, degraded or silly character of the American people. Mark and Martin both nearly die in Eden of malaria. Mark finally finds himself in a situation in which it can be considered a virtue to remain in good spirits. But the grim experience, and Mark's unselfish care nursing Martin back to health, changes Martin's selfish and proud character, and the men return to England, where Martin is resolved to return penitently to his grandfather, humbled and changed. But his grandfather is now apparently under Mr. Pecksniff's control and rejects him coldly (to Pecksniff's glee).

Mr. Pecksniff also becomes financially involved in Montague Tigg's insurance scam through the intervention of Jonas, who is being blackmailed by Tigg, who has acquired some kind of information on Jonas. The information is not revealed until the end of the book, but it is implied that he has evidence that Jonas killed his father.

On his return to England, Young Martin is reunited with Tom Pinch. At this point, Jonas Chuzzlewit murders Montague Tigg when the insurance scam is failing, in order to prevent him from revealing the information he's been using as blackmail. Meanwhile, Tom Pinch discovers that his mysterious benefactor/employer is old Martin Chuzzlewit. The elder Martin reveals that when he saw the ends to which greed would take one (in the case of Jonas and Anthony), he decided to sit back and pretend to be in doddering thrall to Pecksniff, while he carefully planned to give everyone enough rope to hang themselves with. He soon realized the evils of Pecksniff and the good of Pinch. Together, the group confronts Mr. Pecksniff with their knowledge of his true character. Mr. Nadgett leads the group to the discovery of Jonas as the murderer of Montague. They also find out from Anthony's devoted employee Chuffey that Jonas did not murder his father, but did plan to murder him, and in fact thought he had (with poison), when really the father died of a broken heart when he realized his own son wanted him dead. Martin also reveals that he was angry at his grandson for becoming engaged to Mary because he had all along planned to arrange that particular match, and felt his glory had been thwarted by them deciding on the plan themselves, instead. He realizes the folly of that opinion, and Martin and his grandfather are reconciled. Martin and Mary are married, as are Ruth Pinch and John Westlock, and the other characters generally get what they deserve, good or bad. Tom Pinch, however, remains in unrequited, undeclared love with Mary for the rest of his life, never marrying, and always being a warm companion to Mary and Martin and to Ruth and John. The goodness of his heart is such that he is glad to see his loved ones happy, even though he does not partake of this joy himself.

Characters in Martin Chuzzlewit

The Chuzzlewit extended family

The main characters of the story are the members of the extended Chuzzlewit family.

The first to be introduced is Seth Pecksniff, a widower with two daughters, who is a self-styled teacher of architecture. He believes that he is a highly moral individual who loves his fellow man, but mistreats his students and passes off their designs as his own for profit. He seems to be a cousin of Old Martin Chuzzlewit. Mr. Pecksniff's rise and fall follows the novel's plot arc.

Next we meet his two daughters, Charity and Mercy Pecksniff. They are also affectionately known as Cherry and Merry, or as the two Miss Pecksniffs. Charity is portrayed throughout the book as having none of that virtue after which she is named, while Mercy, the younger sister, is at first silly and girlish in a manner that's probably inconsistent with her numerical age. Later events in the story drastically change her personality.

Old Martin Chuzzlewit, the wealthy patriarch of the Chuzzlewit family, lives in constant suspicion of the financial designs of his extended family. At the beginning of the novel he has aligned himself with Mary, an orphan, in order to have a caretaker who is not eyeing his estate. Later in the story he makes an apparent alliance with Mr. Pecksniff, who, he believes, is at least consistent in character. His true character is revealed by the end of the story.

Young Martin Chuzzlewit is the grandson of Old Martin Chuzzlewit. He is the closest relative of Old Martin and has inherited much of the stubbornness and selfishness of the old man. Young Martin is the protagonist of the story. His engagement to Mary is the cause of estrangement between himself and his grandfather. By the end of the story he becomes a reformed character, realizing and repenting of the selfishness of his previous actions.

Mr. Anthony Chuzzlewit is the brother of Old Martin. He and his son, Jonas, run a business together called Chuzzlewit and Son. They are both self-serving, hardened individuals who view the accumulation of money as the most important things in life.

Jonas Chuzzlewit is the mean-spirited, sinisterly jovial son of Anthony Chuzzlewit. He views his father with contempt and wishes for his death so that he can have the business and the money for himself. It is suggested that he may have actually hastened the old man's death. He is a suitor of the two Miss Pecksniffs, wins one, then is driven to commit murder by his unscrupulous business associations.

Other characters

Thomas (Tom) Pinch is a former student of Mr. Pecksniff's who has become his personal assistant. He is kind, simple, and honest in everything he does, serving as a foil to Mr. Pecksniff. He carries in his heart an undying loyalty and admiration for Mr. Pecksniff. Eventually, he discovers Pecksniff's true nature through his treatment of Mary, for whom Pinch develops a love. Because Tom Pinch plays such a large role in the story, he is sometimes considered the novel's true protagonist.

Ruth Pinch is Tom Pinch's sister. She is sweet and good, like her brother. At first she works as a governess to a wealthy family with several nasty brats. Later in the novel she and Tom set up housekeeping together. She falls in love with and marries Tom's friend John Westlock.

Mark Tapley, the good-humoured employee of the Blue Dragon Inn and suitor of Mrs. Lupin (the Dragon's owner), leaves that establishment in order to find work that's more of a credit to his character: that is, work sufficiently miserable that his cheerfulness will be more of a credit to him. He eventually joins Young Martin Chuzzlewit on his trip to America, where he finds at last a situation that requires the full extent of his innate cheerfulness of disposition. Martin buys a piece of land in a settlement called "Eden" — which, if not actually underwater, is at least in the midst of a malarial swamp. Mark nurses him through his illness, and they eventually return to England.

Montague Tigg/ Tigg Montague is a down-on-his-luck rogue at the beginning of the story, and a hanger-on to distant Chuzzlewit kin Chevy Slyme. Later, he starts a thriving, sleazy insurance business with no money at all and lures Jonas into the business. (The Anglo-Bengalee Disinterested Loan and Life Assurance Company is in essence a classic Ponzi scheme—founded before Charles Ponzi was born—which paid off early policyholders' claims with premiums from more recent policyholders.)

John Westlock begins as a disgruntled student falling out with Pecksniff. After Tom Pinch's flight to London, John serves as a mentor and companion to both Tom and his sister; he falls in love with and eventually marries Ruth Pinch.

Mr. Nadgett is a soft-spoken, mysterious individual who is Tom Pinch's landlord and serves as Montague's private investigator.

Sarah Gamp (also known as Sairey or Mrs. Gamp) is an alcoholic who works as a nurse, midwife, and layer-out of the dead. Even in a house of mourning, Mrs. Gamp manages to enjoy all the hospitality a house can afford, with little regard for the person to whom she is there to minister; and she is often much the worse for drink. In her nursing activities, she constantly refers to a Mrs Harris, who is in fact "a phantom of Mrs Gamp's brain ... created for the express purpose of holding visionary dialogues with her on all manner of subjects, and invariably winding up with a compliment to the excellence of her nature." She habitually carries with her a battered black umbrella: so popular with the Victorian public was the character that Gamp became a slang word for an umbrella in general.

Mary Graham is the caretaker of old Martin Chuzzlewit, who has told her she will receive nothing from him in his will. The older Martin expects that this will give Mary a strong interest in keeping him alive and well. Mary and Old Mr. Chuzzlewit's grandson fall in love, thus giving her an interest in the elder Chuzzlewit's death. The two lovers are separated by the events of the book, but are eventually reunited.

Mr. Chuffey is an old man who works for Anthony Chuzzlewit and later Jonas Chuzzlewit.

Publication

Martin Chuzzlewit was published in 19 monthly instalments, each composed of 32 pages of text and two illustrations by Hablot K. "Phiz" Browne and costing one shilling. The last part was double-length.

- I - January 1843 (chapters 1-3)

- II - February 1843 (chapters 4-5)

- III - March 1843 (chapters 6-8)

- IV - April 1843 (chapters 9-10)

- V - May 1843 (chapters 11-12)

- VI - June 1843 (chapters 13-15)

- VII - July 1843 (chapters 16-17)

- VIII - August 1843 (chapters 18-20)

- IX - September 1843 (chapters 21-23)

- X - October 1843 (chapters 24-26)

- XI - November 1843 (chapters 27-29)

- XII - December 1843 (chapters 30-32)

- XIII - January 1844 (chapters 33-35)

- XIV - February 1844 (chapters 36-38)

- XV - March 1844 (chapters 39-41)

- XVI - April 1844 (chapters 42-44)

- XVII - May 1844 (chapters 45-47)

- XVIII - June 1844 (chapters 48-50)

- XIX-XX - July 1844 (chapters 51-54)

The early monthly numbers were not as successful as Dickens' previous work and only sold about twenty thousand copies each (compared to forty to fifty thousand for the monthly numbers of the Pickwick Papers and Nicholas Nickleby and sixty to seventy thousand for the weekly issues of Barnaby Rudge and The Old Curiosity Shop) causing a break between Dickens and his publishers Chapman and Hall when they invoked a penalty clause in his contract requiring him to pay back money they had lent him to cover their costs. Also, Dickens' scathing satire of American modes and manners in the novel won him no friends on the other side of the Atlantic where the instalments containing the offending chapters were greeted with a 'frenzy of wrath' and the receipt by Dickens of much abusive mail and newspaper clippings from the States (Pearson 1949: 132-33).

Anti-Americanism

The novel was (and is still) seen by some to contain attacks on America, although Dickens himself saw it as satire, similar in spirit to his "attacks" on the people and institutions of England in novels such as Oliver Twist. Americans are satirically portrayed as snobs, windbags, hypocrites, liars, bores, humbugs, braggarts, bullies, hogs, savages, blackguards, murderers and idiots; and the Republic is described as "so maimed and lame, so full of sores and ulcers, foul to the eye and almost hopeless to the sense, that her best friends turn from the loathsome creature with disgust". Dickens also attacks the institution of slavery in America in the following words: "Thus the stars wink upon the bloody stripes; and Liberty pulls down her cap upon her eyes, and owns oppression in its vilest aspect for her sister" (Pearson 1949: 129-29).

In order to clarify his intent and purpose as satire and show his respect for the United States, Dickens in 1868 added a Postscript in "The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewi, published by Chapman & Hall Ltd; and Henry Frowde, the following:

At a Public Dinner given to me on Saturday the 18th of April, 1868, in the city of New York, by two hundred representatives of the Press of the United States of America, I made the following observations, among others:--

"So much of my voice has lately been heard in the land, that I might have been contented with troubling you no further from my present standing-point, were it not a duty with which I henceforth charge myself, not only here but on every suitable occasion, whatsoever and wheresoever, to express my high and grateful sense of my second reception in America, and to bear my honest testimony to the national generosity and magnanimity. Also, to declare how astounded I have been by the amazing changes I have seen around me on every side--changes moral, changes physical, changes in the amount of land subdued and peopled, changes in the rise of vast new cities, changes in the growth of older cities almost out of recognition, changes in the graces and amenities of life, changes in the Press, without whose advancement no advancement can take place anywhere. Nor am I, believe me, so arrogant as to suppose that in five-and-twenty years there have been no changes in me, and that I had nothing to learn and no extreme impressions to correct when I was here first. And this brings me to a point on which I have, ever since I landed in the United States last November, observed a strict silence, though sometimes tempted to break it, but in reference to which I will, with your good leave, take you into my confidence now. Even the Press, being human, may be sometimes mistaken or misinformed, and I rather think that I have in one or two rare instances observed its information to be not strictly accurate with reference to myself. Indeed, I have, now and again, been more surprised by printed news that I have read of myself, than by any printed news that I have ever read in my present state of existence. Thus, the vigour and perseverance with which I have for some months past been collecting materials for, and hammering away at, a new book on America has much astonished me; seeing that all that time my declaration has been perfectly well known to my publishers on both sides of the Atlantic, that no consideration on earth would induce me to write one. But what I have intended, what I have resolved upon (and this is the confidence I seek to place in you), is, on my return to England, in my own person, in my own Journal, to bear, for the behoof of my countrymen, such testimony to the gigantic changes in this country as I have hinted at to-night. Also, to record that wherever I have been, in the smallest places equally with the largest, I have been received with unsurpassable politeness, delicacy, sweet temper, hospitality, consideration, and with unsurpassable respect for the privacy daily enforced upon me by the nature of my avocation here and the state of my health. This testimony, so long as I live, and so long as my descendants have any legal right in my books, I shall cause to be republished, as an appendix to every copy of those two books of mine in which I have referred to America. And this I will do and cause to be done, not in mere love and thankfulness, but because I regard it as an act of plain justice and honour."

I said these words with the greatest earnestness that I could lay upon them, and I repeat them in print here with equal earnestness. So long as this book shall last, I hope that they will form a part of it, and will be fairly read as inseparable from my experiences and impressions of America.

CHARLES DICKENS.

May, 1868.

In popular culture

Lisa Simpson mentions Martin Chuzzlewit in The Simpsons episode "Brother, Can You Spare Two Dimes?": she lists it as one of the books she would receive from the Greater Books of the Western Civilization, an obvious joke regarding the book's comparative unpopularity. The CGI movie Barbie in a Christmas Carol features a snotty cat named Chuzzlewit, who is the pet of Barbie's character, Eden Starling. John Travolta's character quotes from the novel in A Love Song for Bobby Long. The novel features prominently in Jasper Fforde's novel The Eyre Affair. In the Doctor Who episode "The Unquiet Dead", after expressing his admiration for Dickens other works, The Doctor criticizes the work saying, "Mind you, for God's sake, the American bit in Martin Chuzzlewit, what's that about? Was that just padding? Or what? I mean, it's rubbish, that bit."

References

- ^ Hardwick, Michael and Mary Hardwick. The Charles Dickens Encyclopedia. New York:Scribner, 1973.

- Bowen John. Other Dickens : Pickwick to Chuzzlewit. Oxford : Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Jordan, John O. The Cambridge companion to Charles Dickens. New York : Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- Pearson, Hesketh. Dickens. Methuen: London, 1949.

- Purchase, Sean. "'Speaking of Them as a Body': Dickens, Slavery and Martin Chuzzlewit." Critical Survey 18.1 (2006): 1-16.

- Sulfridge, Cynthia. "Martin Chuzzlewit: Dicken's Prodigal and the Myth of the Wandering Son." Studies in the Novel 11.3 (1979): 318-325.

- Tambling, Jeremy. Lost in the American city : Dickens, James, and Kafka. New York : Palgrave, 2001.

External links

Online editions

- Martin Chuzzlewit at Internet Archive.

- Martin Chuzzlewit at Project Gutenberg (plain text and HTML)

- Martin Chuzzlewit, available at University of Adelaide (HTML).

- Martin Chuzzlewit, available at Librivox (audio book)

Works by Charles Dickens Novels The Pickwick Papers (1836–1837) · Oliver Twist (1837–1839) · Nicholas Nickleby (1838–1839) · The Old Curiosity Shop (1840–1841) · Barnaby Rudge (1840–1841) · Martin Chuzzlewit (1843–1844) · Dombey and Son (1846–1848) · David Copperfield (1849–1850) · Bleak House (1852–1853) · Hard Times (1854) · Little Dorrit (1855–1857) · A Tale of Two Cities (1859) · Great Expectations (1860–1861) · Our Mutual Friend (1864–1865) · The Mystery of Edwin Drood (unfinished) (1870)Christmas books A Christmas Carol (1843) · The Chimes (1844) · The Cricket on the Hearth (1845) · The Battle of Life (1846) · The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain (1848)Short stories Sunday Under Three Heads (1836) · The Lamplighter (1838) · A Child's Dream of a Star (1850) · Captain Murderer · The Long Voyage (1853) · The Lazy Tour of Two Idle Apprentices (1857) (with Wilkie Collins) · Hunted Down (1859) · The Signal-Man (1866) · George Silverman's Explanation (1868) · Holiday Romance (1868)Christmas

short storiesA Christmas Tree (1850) · What Christmas is, as We Grow Older (1851) · The Poor Relation's Story (1852) · The Child's Story (1852) · The Schoolboy's Story (1853) · Nobody's Story (1853) · Going into Society (1858) · Somebody's Luggage (1862) · Mrs Lirriper's Lodgings (1863) · Mrs Lirriper's Legacy (1864) · Doctor Marigold's Prescriptions (1865)Short story

collectionsSketches by Boz (1837–1839) · The Mudfog Papers (1837–1838) · Master Humphrey's Clock (1840–1841) · Boots at the Holly-tree Inn: And Other Stories (1858) · Reprinted Pieces (1861)Non-fiction American Notes (1842) · Pictures from Italy (1846) · The Life of Our Lord (1846, published in 1934) · A Child's History of England (1851–1853) · The Uncommercial Traveller (1860–1869)Poetry & plays The Village Coquettes (play, 1836) · The Fine Old English Gentleman (poetry, 1841) · The Frozen Deep (play, 1866) (with Wilkie Collins) · No Thoroughfare: A Drama: In Five Acts (play, 1867) (with Wilkie Collins)Journalism The Examiner (1808–1886) · Monthly Magazine (1833–1835) · Morning Chronicle (1834–1836) · Evening Chronicle (1835) · Bentley's Miscellany (1836–1838) · Master Humphrey's Clock (1840–1841) · The Pic-Nic Papers (1841) · Daily News (1846) · Household Words (1850–1859) · All the Year Round (1858–1870)Collaborations Household Words: The Seven Poor Travellers (1854) (with Wilkie Collins, Adelaide Proctor, George Sala and Eliza Linton) · The Holly-tree Inn (1855) · (with Wilkie Collins, William Howitt, Harriet Parr, and Adelaide Procter) · The Wreck of the Golden Mary (1856) (with Wilkie Collins, Adelaide Proctor, Harriet Parr, Percy Fitzgerald and Rev. James White) · The Perils of Certain English Prisoners (1857) (with Wilkie Collins) · A House to Let (1858) (with Wilkie Collins, Elizabeth Gaskell and Adelaide Procter)

All the Year Round: The Haunted House (1859) (with Wilkie Collins, Elizabeth Gaskell, Adelaide Procter, George Sala, and Hesba Stretton) · A Message from the Sea (1860) (with Wilkie Collins, Robert Buchanan, Charles Allston Collins, Amelia Edwards, and Harriet Parr) · Tom Tiddler's Ground (1861) (with Wilkie Collins, John Harwood, Charles Allston Collins, and Amelia Edwards) · The Trial for Murder (1865) (with Charles Allston Collins) · Mugby Junction (1866) (with Andrew Halliday, Charles Allston Collins, Hesba Stretton and Amelia Edwards) · No Thoroughfare (1867) (with Wilkie Collins)Articles & essays A Visit to Newgate (1836) · Epitaph of Charles Irving Thornton (1842) · In Memoriam W. M. Thackeray (1850) · A Coal Miner's Evidence (1850) · Frauds on the Fairies (1853) · The Lost Arctic Voyagers (1854)Categories:- Copy section to Wikisource

- 1843 novels

- Novels by Charles Dickens

- English novels

- Picaresque novels

- Novels first published in serial form

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.